Many Early Modern European publications claimed to accurately document Indigenous life in the Americas, both pre and post-conquest. However, more often than not, European authors categorized Indigenous knowledge forms and cultural production by what was useful to the colonizing force, what was deemed interesting regardless of utility, and what was deemed harmful and necessary to eradicate in the name of “morality.” This perspective must be acknowledged when it comes to discussing the documentation of Indigenous practice and production.

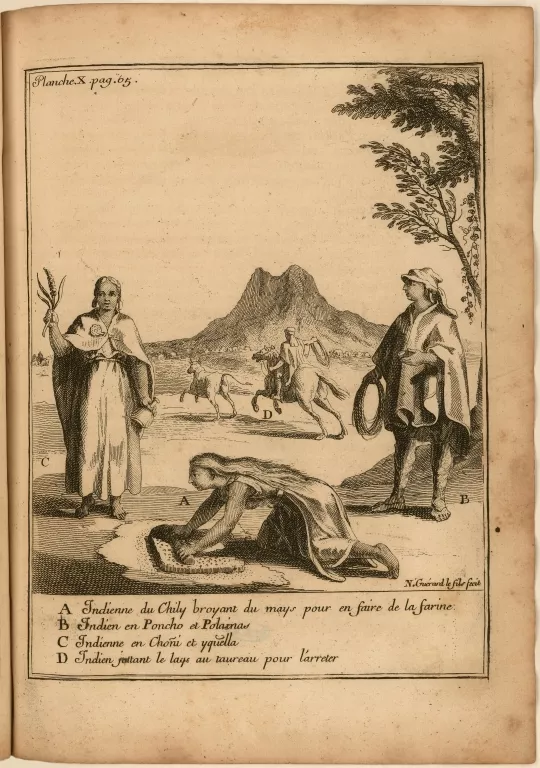

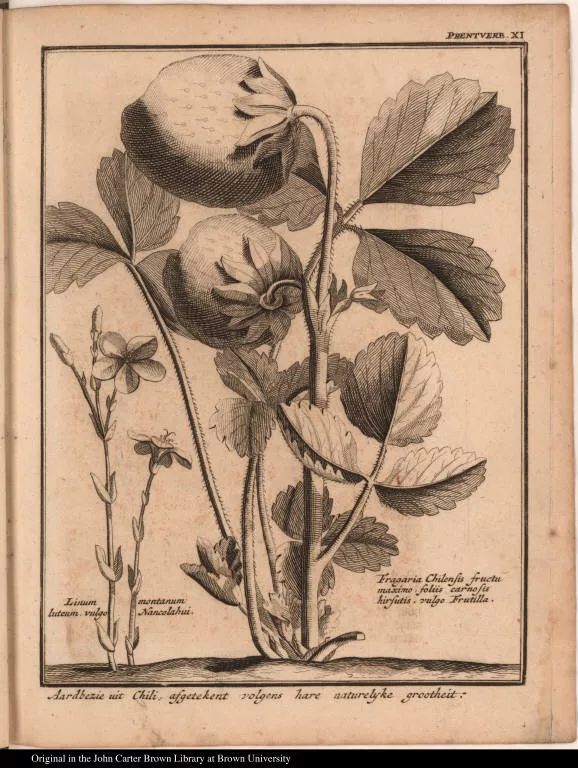

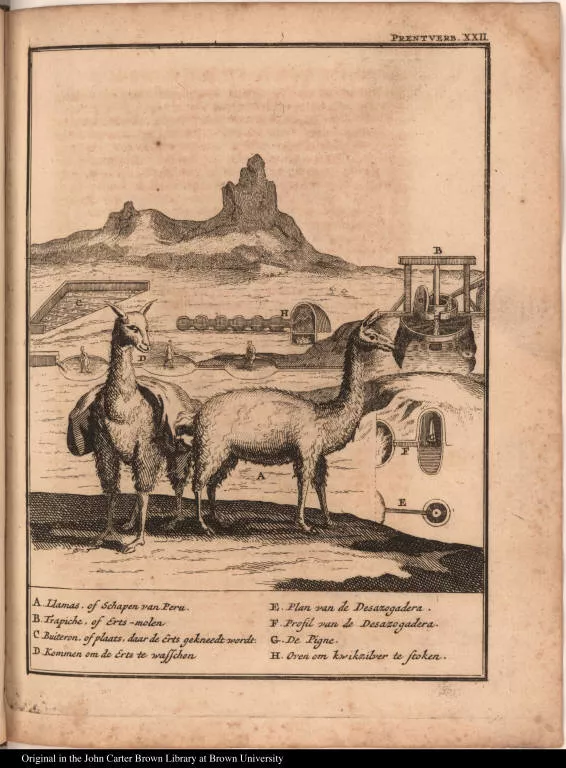

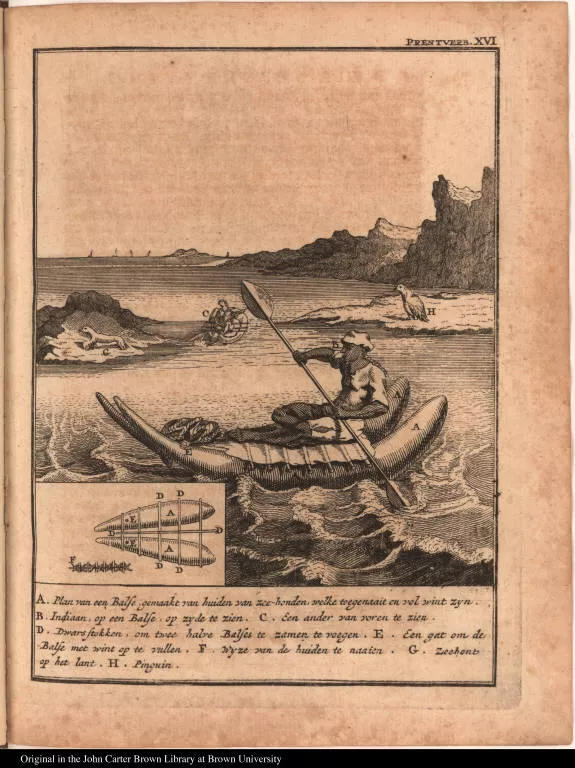

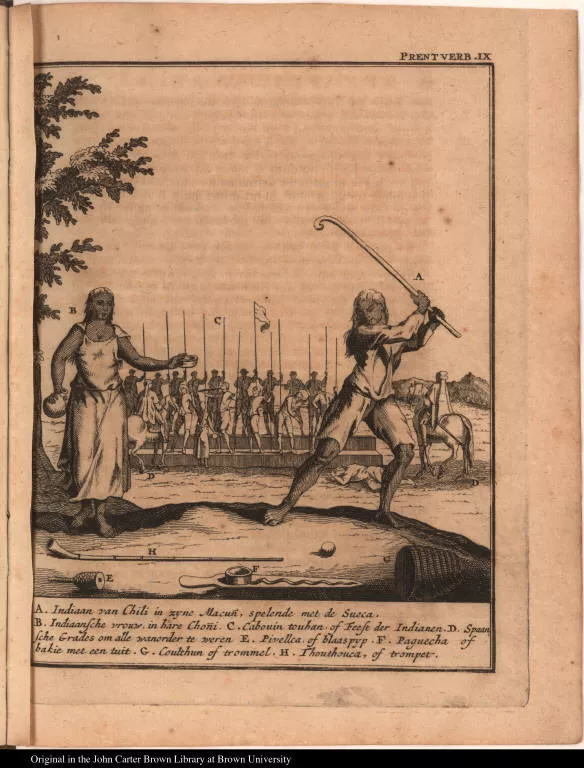

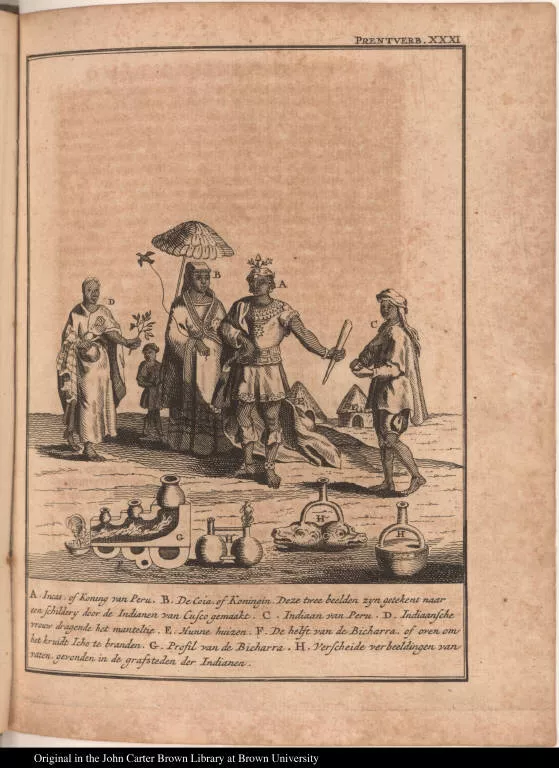

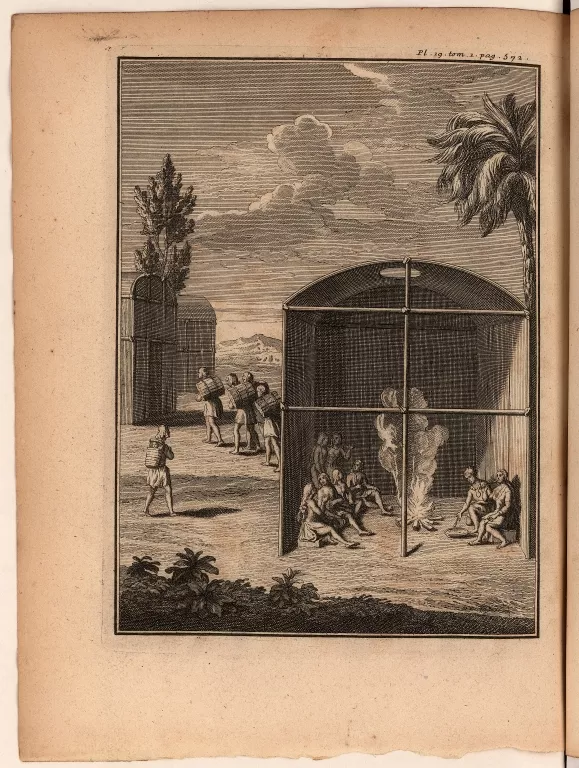

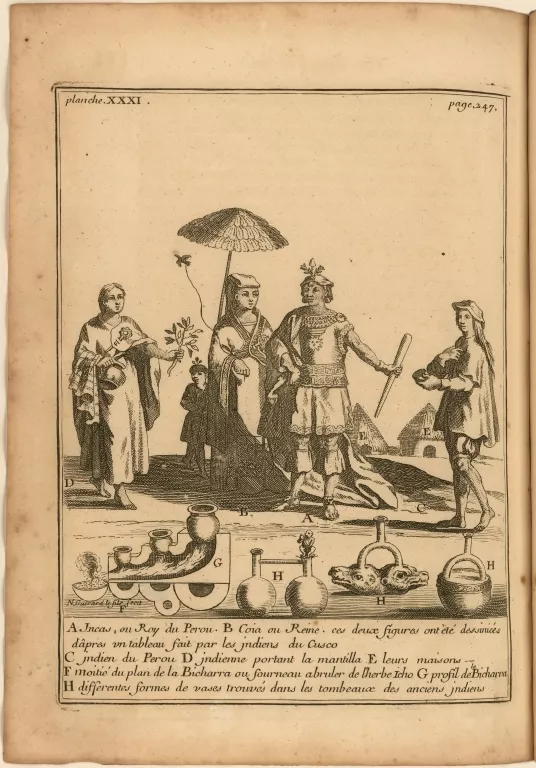

The knowledge coveted and categorized by European colonists and “explorers” is written in a wide variety of Early Modern volumes (those of Frézier, Harriot, de Bry, Lafitau, Clavijero, and Hernández to name a few). For example, the ways Amédée-François Frézier chose to depict the Indigenous practices and knowledge forms he encountered in his travel journal A Voyage to the South-Sea, and Along the Coasts of Chile and Peru, in the Years 1712, 1713, and 1714, reveals how he valued them. Frézier was a French military engineer, mathematician, spy, and explorer under the French King Louis XIV. While his travel journal aims to be informative and honest in its portrayals, Frézier’s documentation of Indigenous peoples and practices is inherently tainted by both his own biases and viceregal opinion and treatment of Indigenous knowledge and production following the conquests of Chile and Peru.

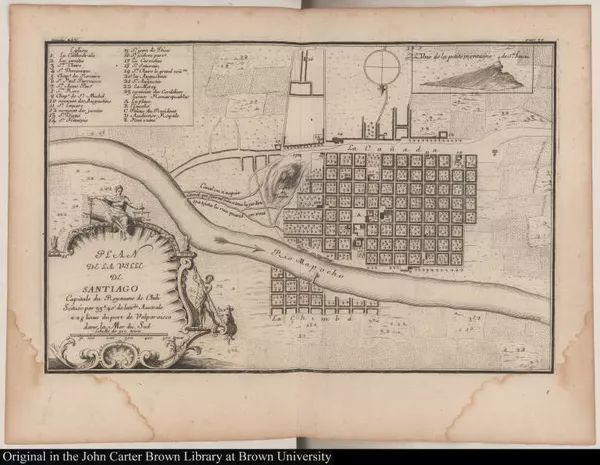

Frézier was sent on a royal mission to collect information and spy on Spanish ports and fortifications along the Pacific coastline of South America, as far North as Callao, the port of Lima. King Louis XIV commissioned the travel journal to identify the land and Indigenous forms of knowledge coveted by the Spaniards in the Americas. The mission was inspired both by Louis XIV’s grandson now sitting on the throne of Spain and allowing long sought out access of the Americas to the French, and by the threat that Spanish dissent towards their new king may cause an overthrow of power and lead to a conflict between the two European nations. Louis XIV appreciated that Frézier, given his background (especially, his knowledge of fortresses and other military structures), would be most capable of making valuable hydrographical observations of the region.

To further satisfy King Louis XIV’s appetite for intelligence with possible military application, Frézier's journal also provided insight into the practices of Indigenous tribes both within and outside of viceregal society. Frézier made special note of indicated dissent towards Spanish rule that could be leveraged by the French should they invade the Viceroyalties. He noted the forms of oppression imposed by the Spanish from which the French could offer to free the Indigenous peoples in exchange for their support in a potential conflict. Frézier also commented on the loyalty, intelligence, and military prowess of the Indigenous Americans.

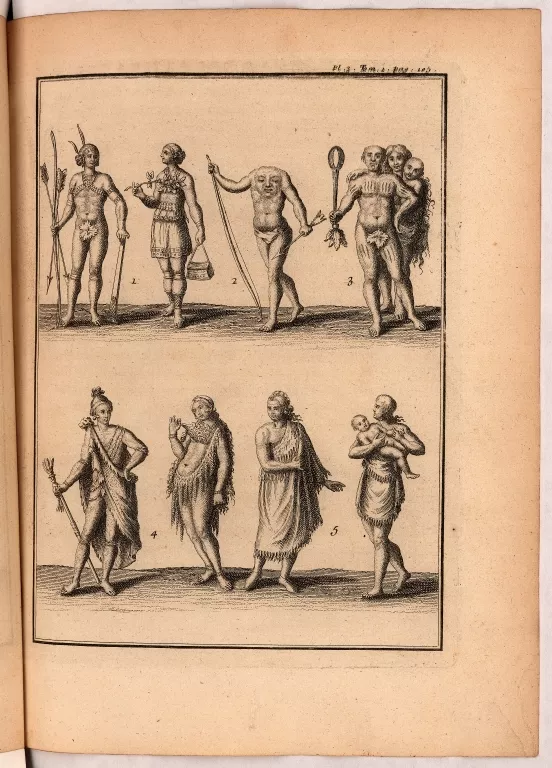

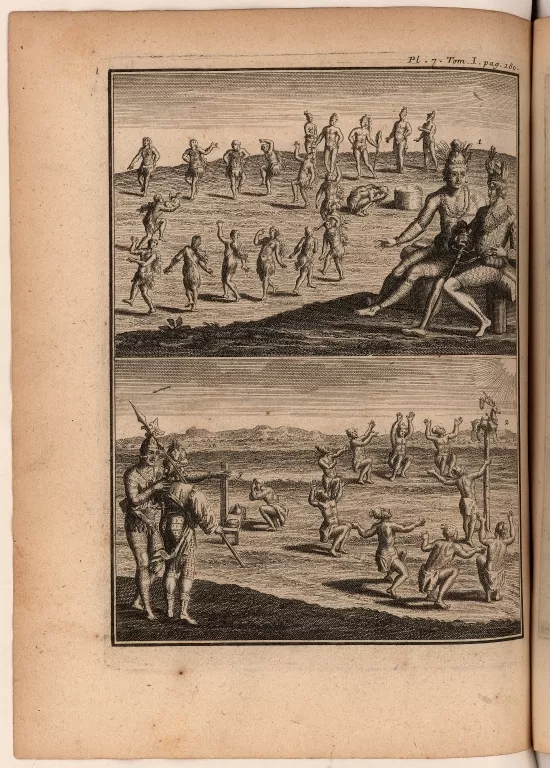

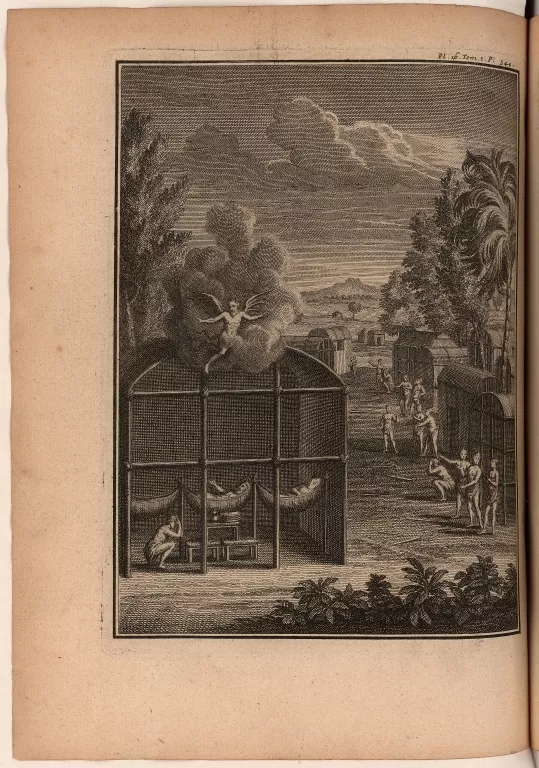

Similar to A Voyage to the South-Sea, Joseph-François Lafitau’s ethnographic study of the Haudenosaunee — or Iroquois — peoples of Eastern Canada, Moeurs des sauvages ameriquains, is corrupted by a European ambition for power and ownership over the “New World.” While Frézier’s travel journal documents Indigenous knowledge and local land in terms of its potential for European economic prosperity, Lafitau’s perspective is oriented more around faith and spirituality. Commissioned by the French state as part of a Jesuit expedition, Lafitau’s analysis centers chiefly around the ceremonial practices of the Haudenosaunee. However, like most all colonial accounts of the early Americas, his documentation is not a straightforward transmission of knowledge, but instead focuses, at times subversively and at others explicitly, on how the Indigenous populations may be of benefit to the French throughout their exploits in a new, foreign, and trying landscape. Lafitau’s interpretation of the Indigenous people contrasts with that of previous explorers. In writings from original travelers like Oviedo, Columbus, and Cabeza de Vaca, the people of the southeast Americas are defined by qualities totally and innately different from those of Europeans. Columbus included in his journal that the Taino people of Hispaniola bore no resemblance to any specimen before identified by Pliny or Marco Polo, and therefore, were compared to creatures of a new and mythic world (Jane, 40). Hence, the narrative of “monstrous man” came to be attached to the Indigenous of the Americas, peoples unlike any previously known. Lafitau also quotes ancient European scholars in his analysis of the Indigenous, but does so in order to make a contrasting argument. According to an analysis of the book by David Harvey, Lafitau’s central argument is that all members of the human species are of the same holy seed (Harvey, 77) . Referencing classic canonical texts from Greece, Lafitau asserts that the Haudenosaunee were similar, in appearance and spiritual tradition, to ancient Europeans and some Asian societies (see pages 125, 277, and 305). By comparing the Indigenous peoples of America to his European ancestors, Lafitau suggests that the Haudenosaunee exist on the same linear evolution of humanity, only thousands of years behind Europeans. Conveniently, his argument acts to support the greater European ambition of conversion in the Americas. Because they are of the same seed, Lafitau insists, it would be the moral responsibility of European settlers to ‘enlighten’ the Haudenosaunee, who were expected to be susceptible to the Jesuit faith. In most all European accounts of the Indigenous, interpretation is affected by ulterior interests, however, in the case of Moeurs des sauvages ameriquains, Lafitau’s affected interpretation is non-conventional.

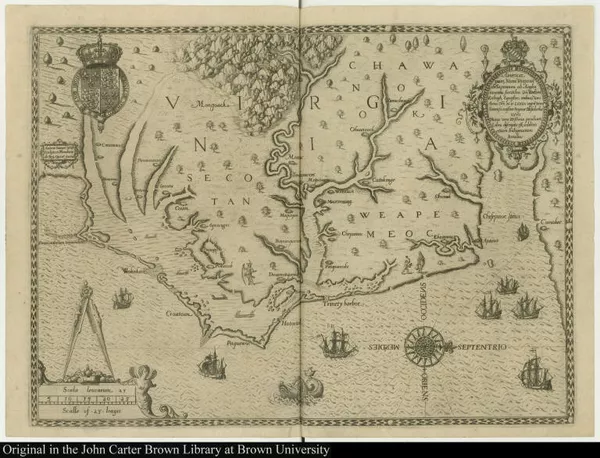

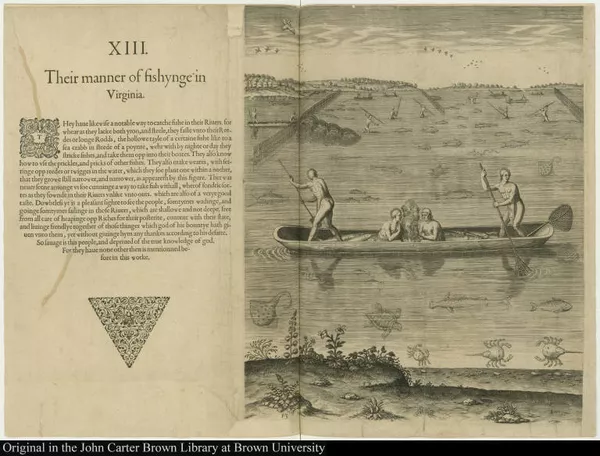

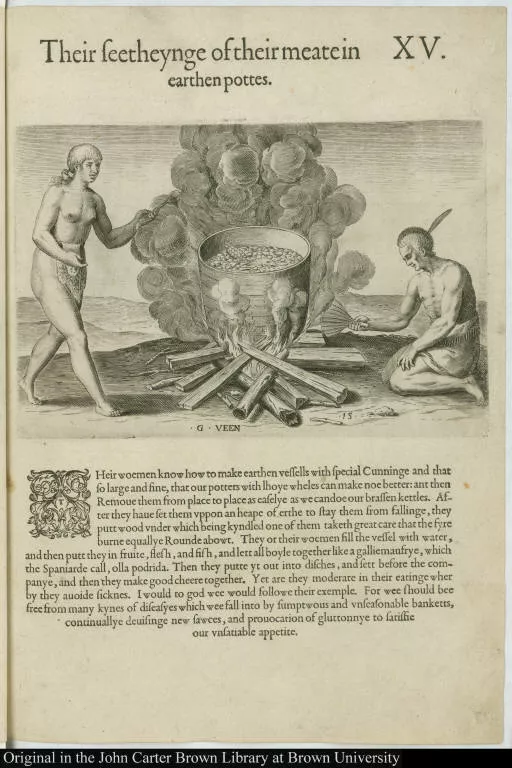

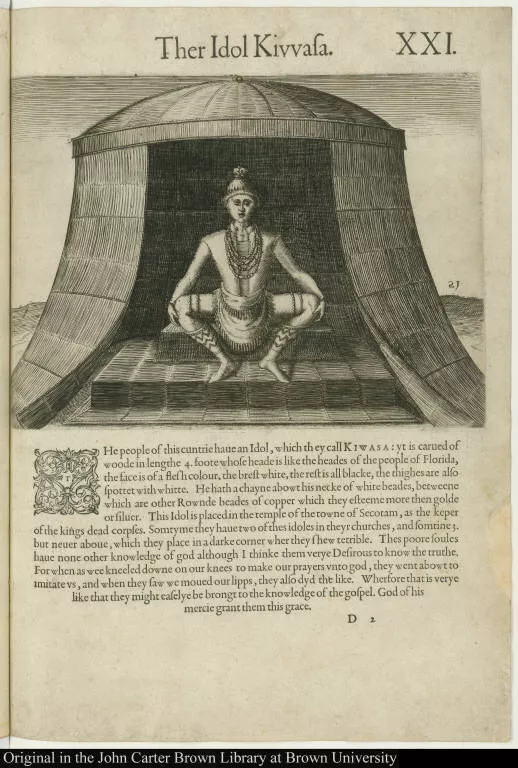

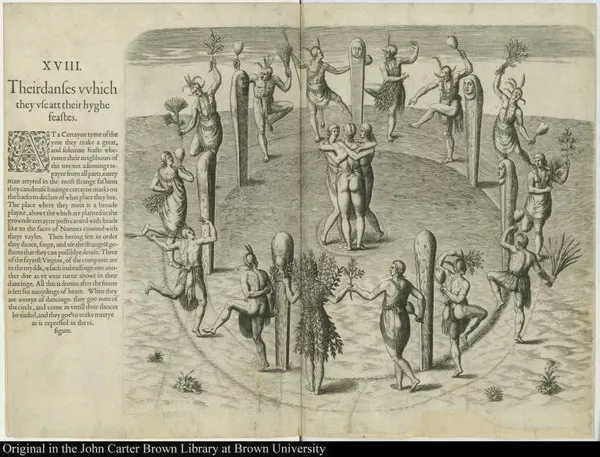

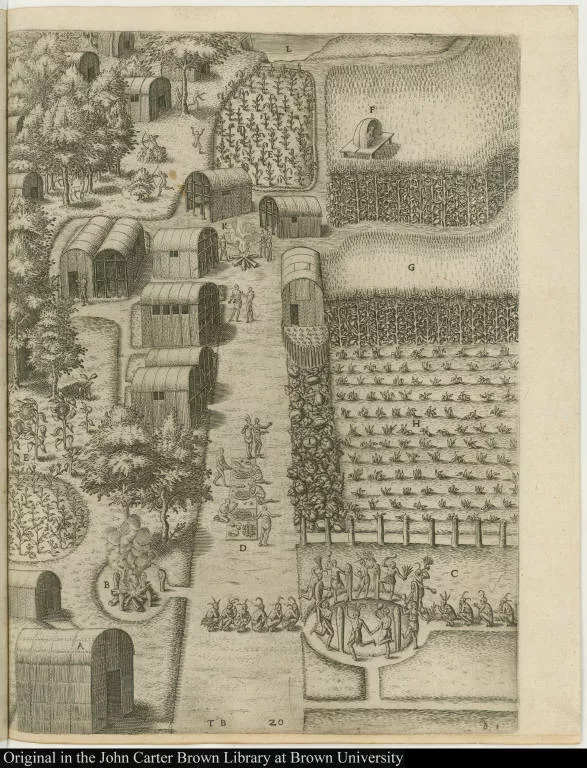

Similarly, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia was also part of a mission to inspire potential English investors and settlers. The author Thomas Harriot was a mathematician, astronomer, linguist, and philosopher. He and the book’s illustrator John White both participated in an English expedition to the Roanoke Island in modern-day North Carolina in June 1585. In 1588, Thomas Harriot published in England a small octavo edition of A Briefe and True Report that served as propaganda for Raleigh’s colony. Harriot presented Virginia as a land abundant of commercially viable and edible plants and animals, and enlightened his English audience with practical information necessary for their survival. He divided his catalog of a variety of the flora and fauna into three parts: “merchantable commodities,” which included silk, wine, and copper; “commodities to yield for victual and sustenance of man’s life,” which included maize, fruits, and fish; and finally “other things that would be useful for those which shall plant and inhabit to know of,” such as timber and lime. It is obvious that all three sections of Harriot detailed catalog were speaking to the English audience about the New World as a land of wealth that they could explore and exploit. It is worth noting that the pioneers of English colonization of the New World were not paid wages but were promised shares in the colony's profits and grants of land as well as a voice in their own civil government (Sistrom). Therefore, for Harriot and White, who later returned to Roanoke in 1587 as governor, their goal was to bring in more European support and investment—and they successfully did so, by crafting a coherent argument in favor of colonization and describing the means by which colonies would benefit their sponsors, settlers, and the nation, which arguably lead to the landing at Jamestown as England's first permanent settlement in America in 1607. We can now better understand A Briefe and True Report, keeping in mind the historical context and the author’s biases.

Comparable to the other volumes in also being influenced by the desires of their patrons to control and exploit the Americas was Francisco Hernández’s Nova Plantarum, Animalium et Mineralium Mexicanorum Historia. The naturalist guide to the Americas had been commissioned from Hernández by King Philip II of Spain to survey the power and quantity of medicines in his new territories. With its origins, it is evident that the Spanish Empire’s obvious desire to further dominate trade markets in both knowledge and in economic output prompted the volume and its contents, however objective, was occluded by this. Despite Hernández’s interactions with Indigenous knowledge keepers in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, or present-day Mexico, guiding the production of the work, its use was inherently violent due to the patron's intent to exploit it. By lending this information to the Spanish crown, European imperial powers gained a better understanding of the workings of American agricultural and medicinal cultivation practices, encouraging further exploration and exploitation of American resources. This expansion of viceregal power would only add to the erasure of Indigenous peoples, practices, and ways of knowing.

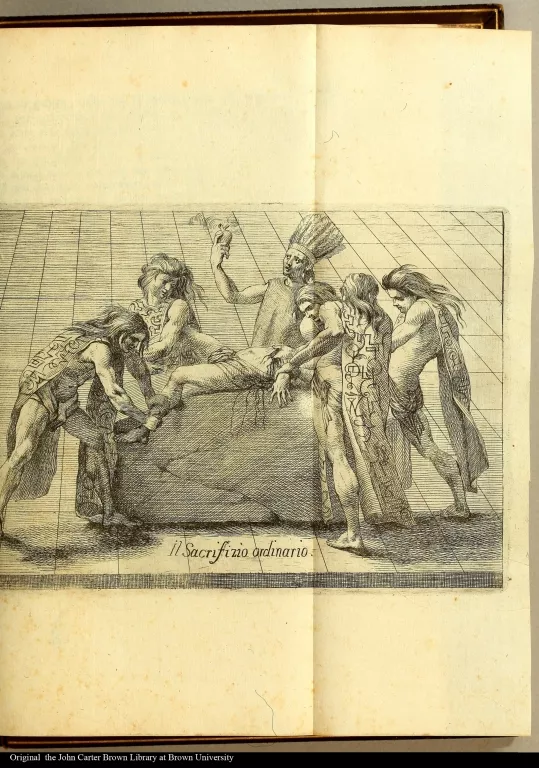

La Storia Antica del Messico, published by Mexican historian and Jesuit friar Francisco Javier Clavijero Echegaray, is but another publication that took advantage of the European intellectual market that came to surround the Americas. Clavijero was a historian of Mexico both pre- and post- conquest and composed his work with the goal of dispelling the insular and polarized accounts of the region he encountered. Though he had set about composing his own history of Mexico due to restore truth to the false accounts that permeated the market, Clavijero wrote for an audience that he knew would value and legitimize his knowledge. However, despite his enterprise having the seemingly noble, objective goal of de-stigmatizing the Americas, Clavijero, like his contemporary counterparts, was not always truthful to his sources. The volume was yet another text that utilized racial stereotypes and false accounts of Indigenous pre-conquest religious practice to encourage further conversion to Christianity. To further this goal of encouraging evangelization in the Americas, Clavijero also drew extensively from exaggerated accounts of Mexica ritual sacrifice to further stimulate the moral and religious justifications of colonial enterprise.