Colonial representations of Indigenous language are constructions subject to power relations, being that they are recorded / transliterated / altered through conflicting webs of the motivations of their authors / publishers / audiences. These representations are presented in colonial books on the Americas, written for European audiences, and preserved for a variety of reasons with a variety of effects. Words recorded by Europeans in Indigenous languages often reflect colonial desires for legibility and control of the Americas and its peoples. In analyzing the histories of these processes, two colonial texts were mainly consulted, each from different time periods and recording data on different regions. Despite disparity in time and location, these texts nevertheless reveal important information about settler colonial logics and discourses.

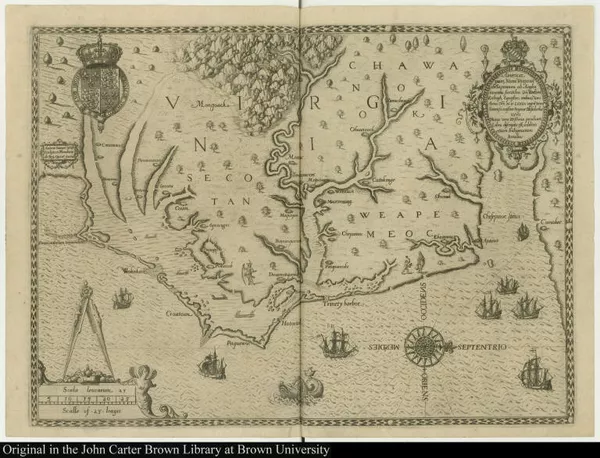

In 1584, Sir Walter Raleigh traveled to the land that is now known as Virginia. There, he encountered the Indigenous peoples of the region, as well as the local flora and fauna. In the hopes of establishing a colony, he coerced two Algonquian men — Manteo and Wanchese — to return to England with him. During the winter of 1584-85, these men taught English astronomer, mathematician, ethnographer and translator Thomas Harriot the basics of Algonquian language. In the summer of 1585, Harriot returned to Virginia with Raleigh in the hopes of exploring, mapping, and cataloging the surrounding land, people, and wildlife. Harriot used a multitude of uncited Indigenous informants to perform this task, and the information he produced was published in A Briefe and True Report on The New Found Land of Virginia (Frankfurt am Main, 1590). John White, an artist who traveled with Harriot and the eventual governor of the Roanoke colony, mapped the territory and produced watercolor paintings that were later translated into woodblock engravings to lavishly decorate the publication. This publication, composed by the de Bry printhouse, mainly served to catalog the natural resources of Virginia in hopes of enticing settlers and investment to Raleigh’s colony on Roanoke island. As the first book published by English colonists who actually traveled to the Americas, it was heavily influential on future colonization efforts and discourse.

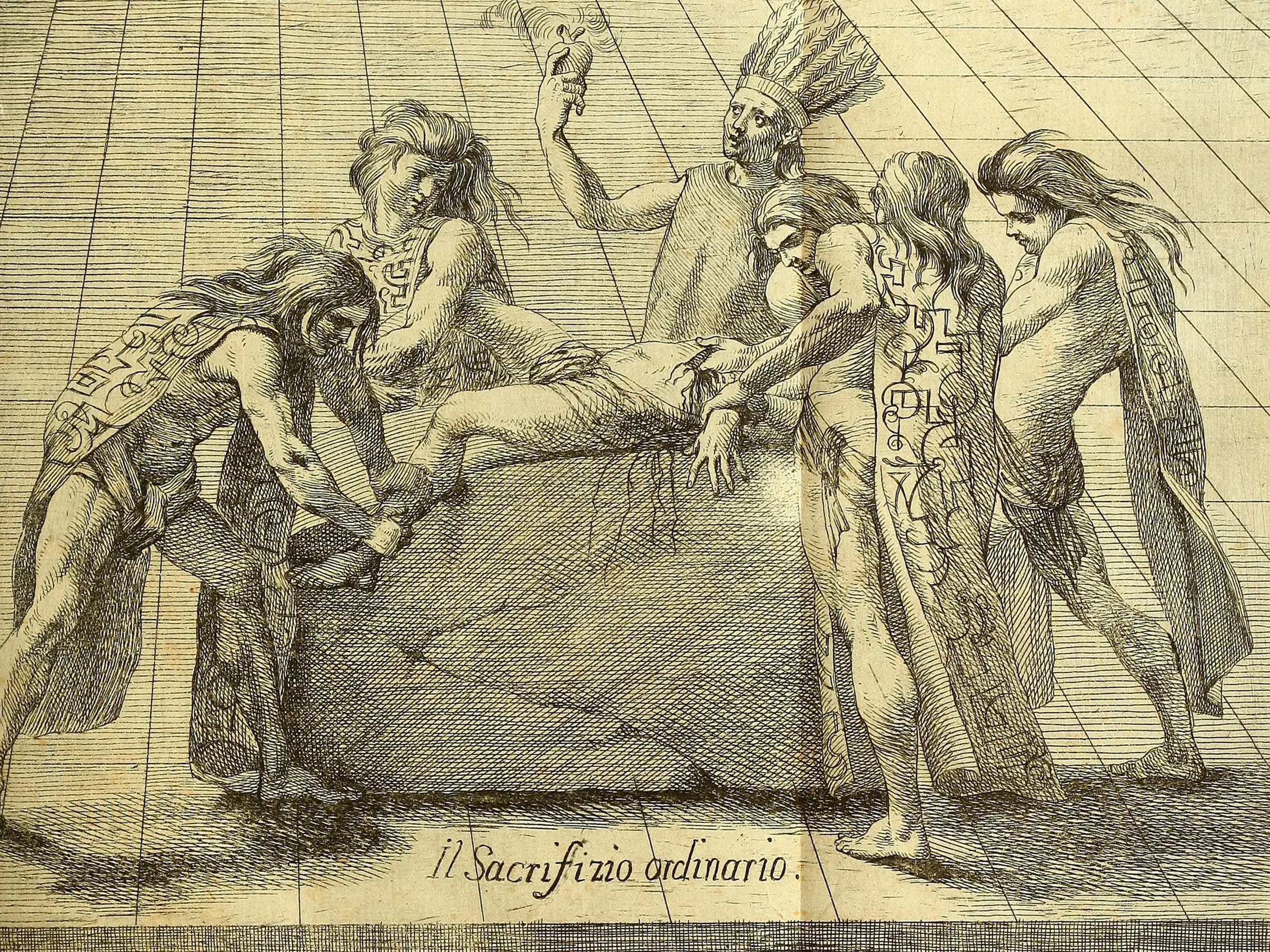

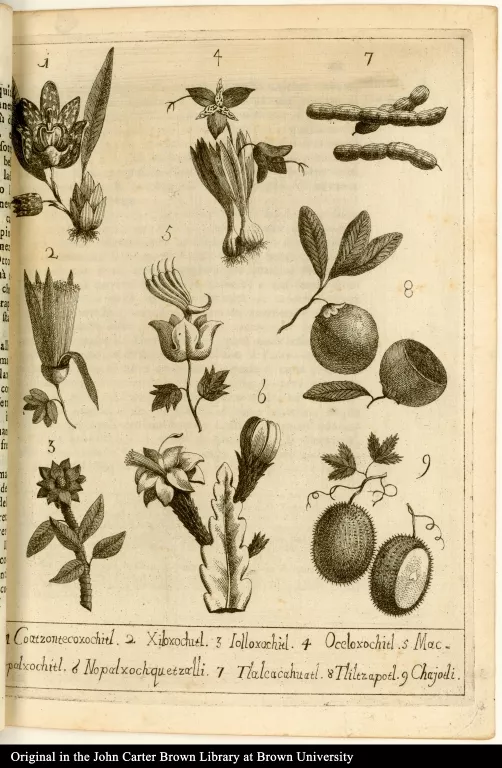

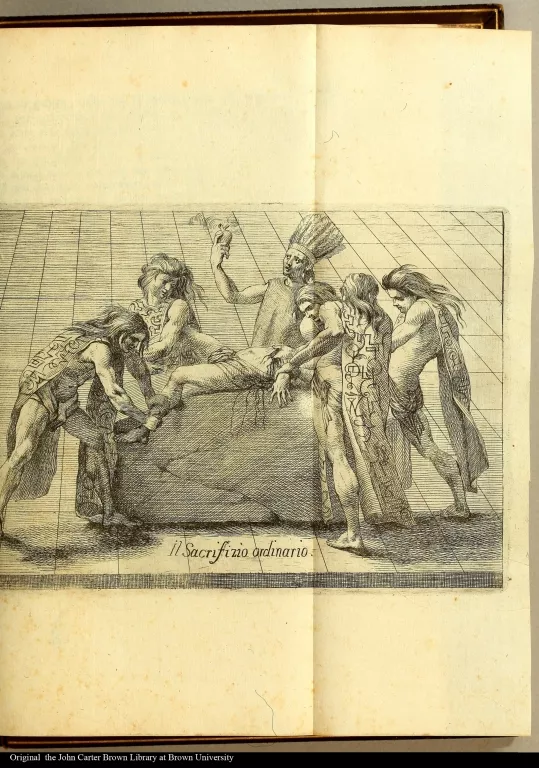

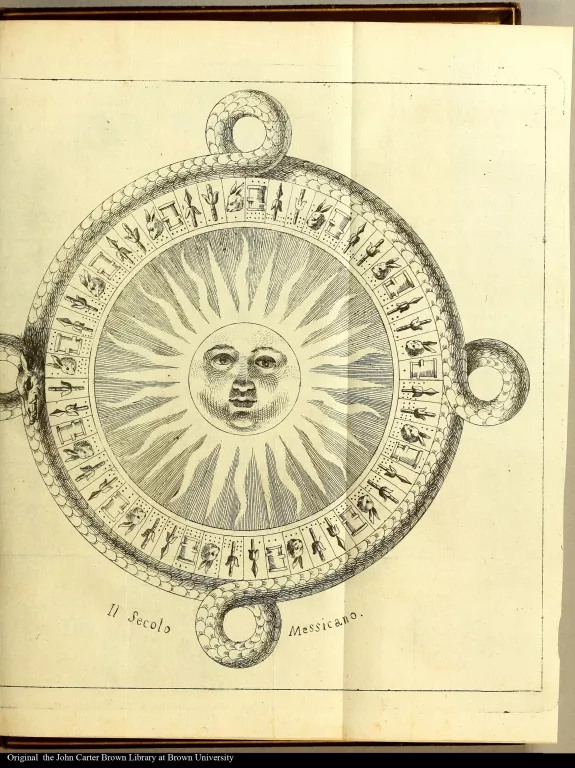

Almost two hundred years after Raleigh and Harriot’s expedition, the Historia antica del Messico, another book containing information about the Americas, was published in Cesena, Italy in 1780. This book’s author — Jesuit friar Francisco Clavigero — wrote about the landscape and peoples of Anahuac, a region in which the text identifies groups of Indigenous peoples and their culture along with various Nahuatl words. Clavigero wrote the manuscript for this text prior to the Jesuit expulsion from the Americas in 1767, after which he settled in Italy. There, Clavigero translated the book into Italian, and commissioned artists to produce some of the images he would be unable to lift from older colonial books (most notably the Nova plantarum, 1651) to accompany the text. Seven years after the Italian publication, the Third Earl of Bute requested an English translation be made. The book’s contents described the geography, flora/fauna, peoples, military history, political lineages, colonization, religion, and culture of Anahuac, primarily for the purposes of converting the Mixteca/Nahua peoples to Christianity, encouraging settlement, and displaying Clavigero’s own sentimentality towards the region. The book was an early example of a “modern” colonial history, and was influential in Thomas Jeffersons’ early theorizations of archaeological practice (Winterer, 96).