European entanglements with the Americas challenged many fundamental beliefs of Western Christianity. Before 1492, the European imagination of the world stretched only so far as Fisterra, the westernmost point of Spain. Suddenly, there was an entirely new geographical history to be stitched into the seemingly cemented dogmas of their religious belief. According to contemporary Christian interpretations of Genesis, all of humanity descended from Shem, Ham, and Japhet, the three sons of Noah. Did the discovery of an entirely new group of people, existing across thousands of miles of ocean, with entirely separate spiritual understandings of their own, challenge the claims of Genesis? Could all people, even those Indigenous to the foreign Americas, stem from Adam and Eve?

Certain European thinkers like the German Protestant physician-philosopher Paracelsus believed that Native Americans stemmed from a separate creation, while others upheld the longstanding belief that all humanity came from a universal religious origin. In his 350-page exploration of Native religious practice and belief, Joseph-François Lafitau tried to prove that all humans and their spiritual beliefs derived from one singular and natural religion of man. Through comparing his insight into Iroquois practice with his studies of Classical and ancient Christian texts, Lafitau argued that all of humanity stemmed from the same seed.

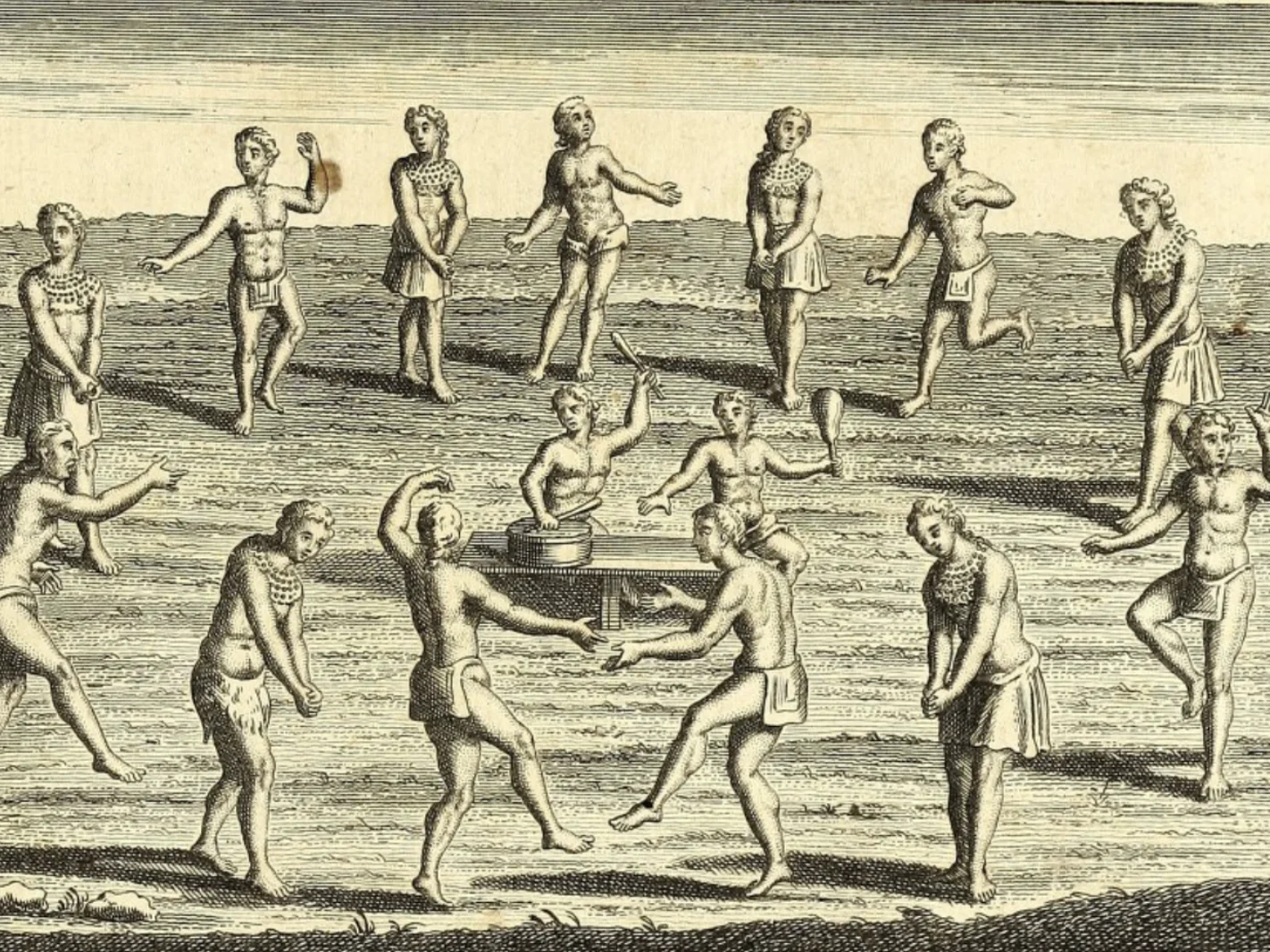

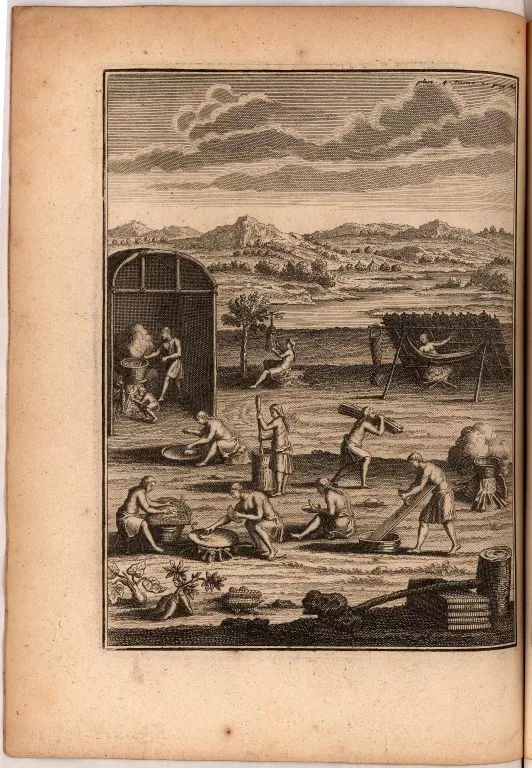

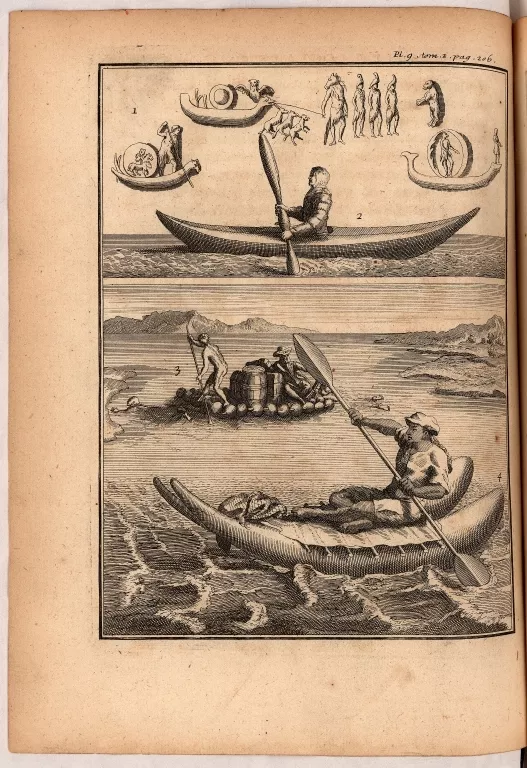

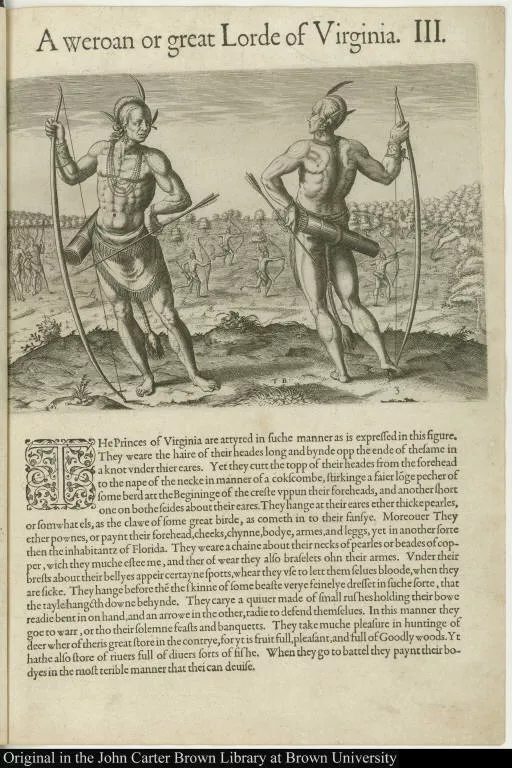

While we cannot ignore the harm Lafitau’s methods, and the Jesuit missionary project, caused, it must also be noted that his ethnographic account of Native Americans took an arguably more favorable view than the narratives spun by his predecessors and many who followed later. It was only the century before during which Spanish theologian Juan de Sepúlveda argued that the Native Americas were “natural slaves” in the Valladolid debate against the Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas. Even the later construction of “noble savages” painted an image of the Indigenous as lawless, without clothes, without property, without ideology, and without religion. Regardless of his missionary ambitions, Lafitau’s first-hand study and account of Native religious belief gave more autonomy to the Iroquois than was standard for previous expeditions. To define their culture, regardless of the motivation, was to define the Indigenous as human, which, for the time, was not the standard.

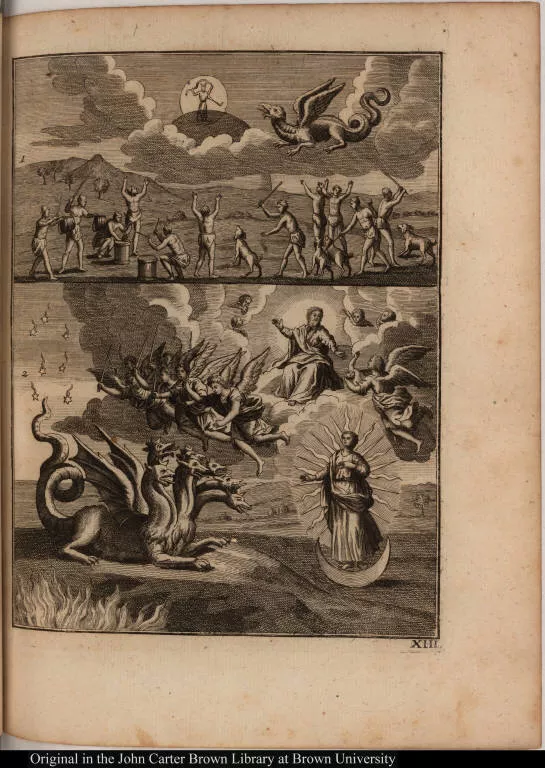

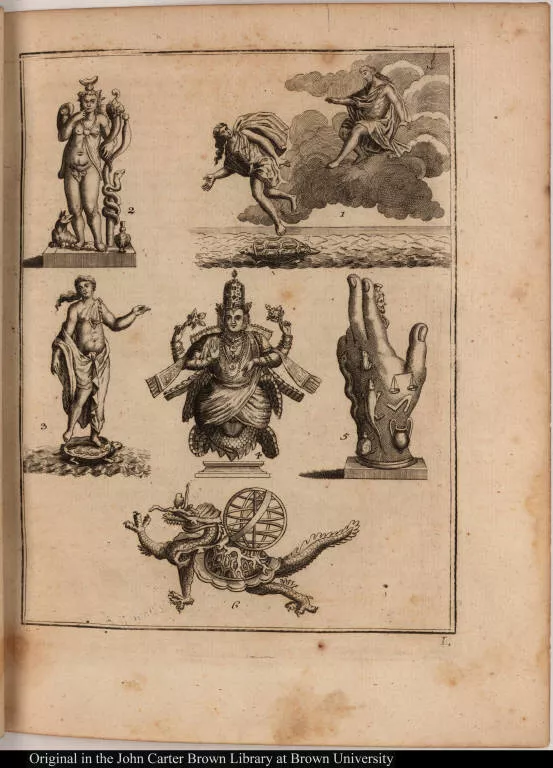

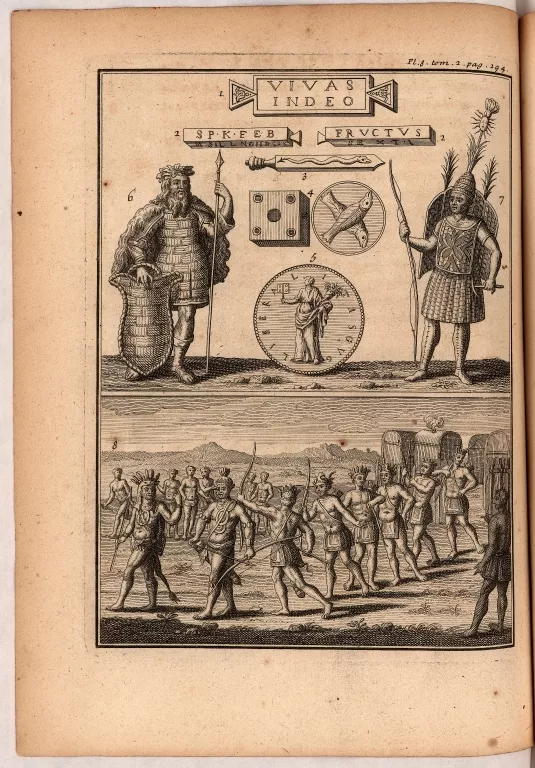

What were Lafitau’s motivations for comparing the religions of his forefathers and the Iroquois people? His goal in writing about their spiritual practice was to uphold the tenets of Genesis, to prove not only a singular and natural religion of humankind, but to also prove an evolutionary ladder on which civilizations were dispersed. For example, on page 94, Lafitau’s illustrator cross-references the common turtle back creation story with ancient religions previously known to Europeans: ancient Greeks and Romans, ancient Egyptians, Hinduism, and ancient Chinese spirituality. In this Native creation myth, a woman falls from the sky into a river and is brought back to the surface on the back of a turtle. That turtle became what many of us now know as North America, what many Native people today call Turtle Island. This story is presented alongside images from these other religions that include turtles as symbols. Through this comparison, this print suggests that Iroquois religion was connected to other ancient world religions, supporting Lafitau’s argument that all humankind originally shared a universal faith. However, in the text itself, Lafitau goes on to discredit the validity of the Indigenous turtle back story, promoting the biblical creation story, and thus his Jesuit mission, instead.

In essence, then, Lafitau claims that Europeans have climbed further up the same evolutionary ladder than the Iroquois. Although Lafitau may not be arguing for the complete and utter genocidal subjugation of the Native Americans, he does leverage religion as a way to argue European superiority, and therefore European duty to spread the (in his opinion) more advanced and precise views of the Jesuit faith.