While each book referenced below was prompted by and written in a unique context, they were all published in 18th-century Europe and distributed in a period of expanding intellectual markets, particularly related to materials dealing with the Americas. Therefore, these books and the information that they contain were all in some way shaped by an appeal to a European reader, despite potential claims of objectivity. Indeed, those claims to objectivity were important in the marketing to that European reader, as they functioned as claims to authority and expertise. It is important to consider both the explicit and more subtle ways that information could have been adapted and — in the process, altered — to be more palatable to a European audience in their struggle for continued colonial rule over American lands, resources, and Indigenous communities.

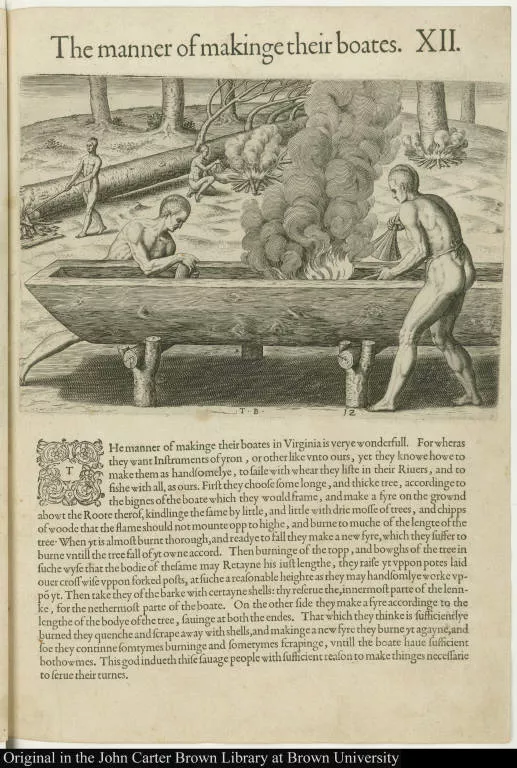

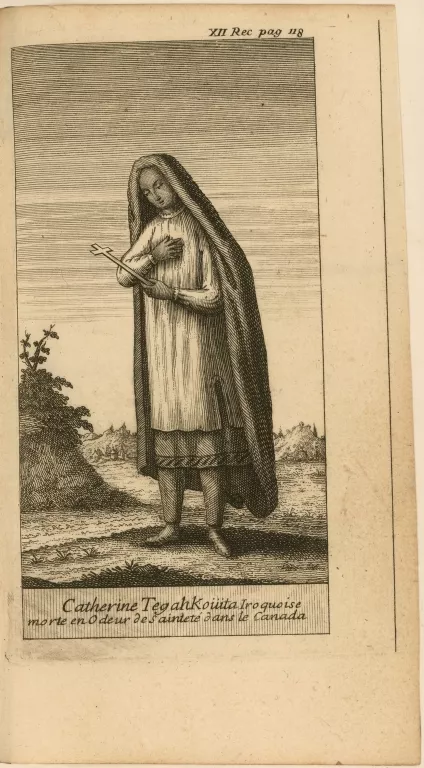

The wealthy and well-educated Jesuit Joseph-François Lafitau was sent to New France (modern-day Canada) as a missionary to join a pre-established mission to the Haudenosaunee people on the banks of what is now the St. Lawrence River. His book, Mœurs des Sauvages Ameriquains, comparées aux mœurs des premiers temps (1724), was, therefore, only published with Jesuit approval and funding. As such, a major stakeholder in Lafitau’s writing was the Catholic Church, and the audience of the book was likely a mix of prominent members of Jesuit circles and other educated men of science (a common overlapping demographic). Most of it was written while Lafitau was serving as as procurator of French missions to the Americas, an administrative role in the Jesuit order. As such, the intent of his writing was likely to further incentivize more Jesuit missions like the one that he went on, and given his ethnographic interests, likely also to contribute to that burgeoning European science. Further, his text sought to argue that all human religions were of the same holy seed — this seed being Christianity — but had been perverted in other societies. Ultimately, his book served this purpose by arguing that while Indigenous peoples, particularly the Haudenosaunee, were primitive, they were similar to ancient Greco-Roman societies. Therefore Indigenous communities followed the same linear evolution as the rest of humanity in moving toward the true Christian faith, only thousands of years behind Europeans, and were therefore not beyond redemption through conversion.

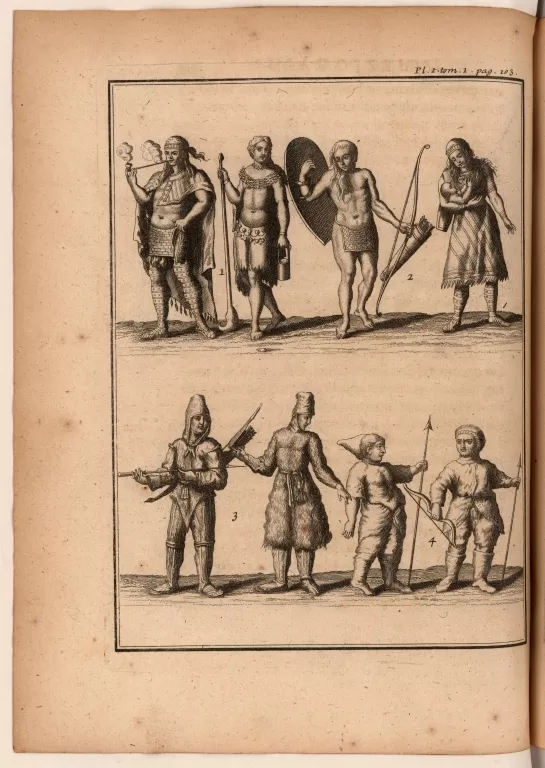

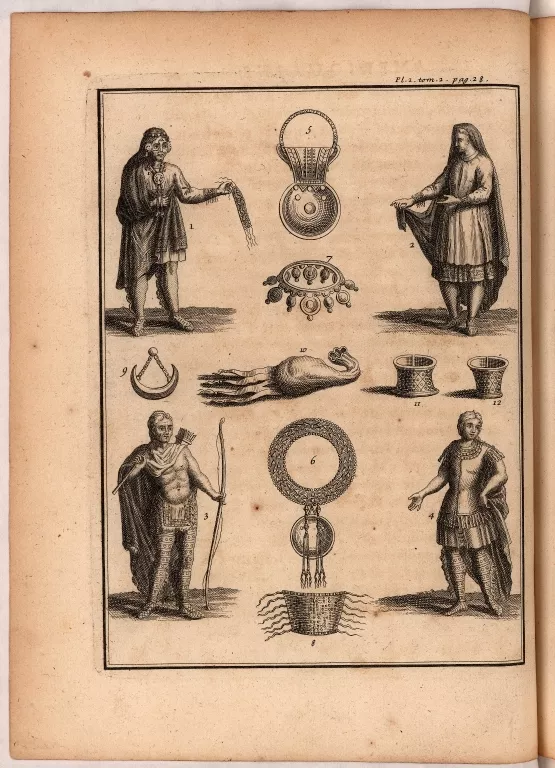

His illustrations, too, depicted Indigenous societies as similar to their Greco-Roman counterparts, which was different from how a lot of his peers chose to show Indigenous people. This angle — which is at the heart of Lafitau's book — suggested that it was justified for members of the Church to make efforts to lead them to God with missions to the Americas. Because the Jesuit community stood directly to benefit from Lafitau’s position and he was happy to abide by the norms of most Jesuit-produced scholarship, there was probably less pressure for him to cite specific, non-Jesuit sources; no one was fighting, standing against, or dissecting the points he was making anyway.

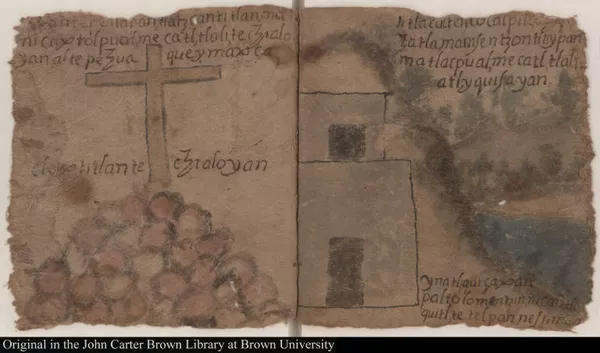

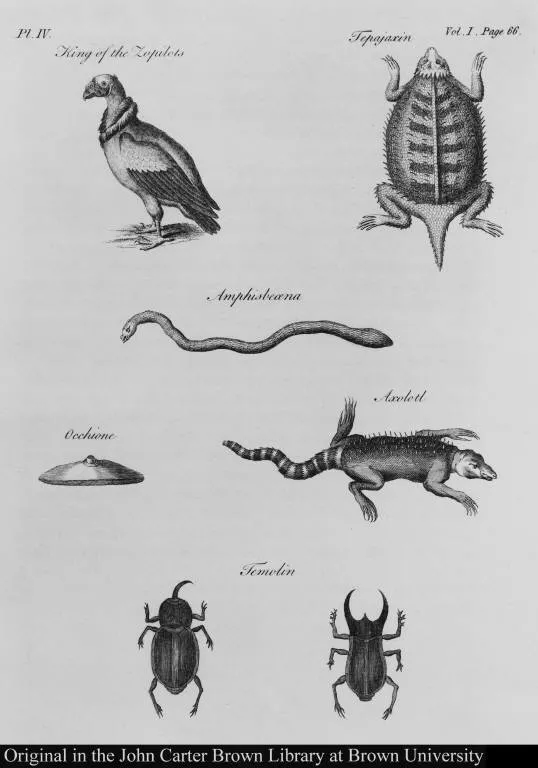

A fellow Jesuit scholar, born in New Spain (Mexico), Francisco Saverio Clavigero, also published a historically-oriented ethnography of North American Indigenous groups, in this case the Nahua peoples. Originally published in Italian, but soon translated into English, German, and Spanish, La storia antica del Messico (1781) was conceptualized and written in a tense and highly competitive European intellectual market. Having been expelled from Mexico in 1767 during the Bourbon reforms which suppressed Jesuit activity, Clavigero relocated to Italy with the intention of continuing his studies on Mexican history. But in this shift, he was met with an insular and polarized body of European writings on the Americas. Often written by authors who themselves had never traveled to Spanish colonial provinces, these books and philosophical papers often reworked existing material — or simply fabricated information — for the sake of painting a more intense and exotic image of the Americas. This image, in entertaining an ignorant audience, reinforced a perceived inferiority (yet, sometimes contradictorily, also an exceptionalism) of the geography, plants, animals, and people of the New World. Cornelius de Pauw, a Dutch philosopher, was a primary advocate of this American Degeneracy Theory and it was his popularity in Europe, particularly after publishing his book Recherches philosophiques sur les américains, which partially prompted Clavigero's own writing (Winterer, 84). Born in Mexico and having spent the most formative part of his life amongst Indigenous communities of the Anahuac (central Mexican plateau), Clavigero set about writing his own history of Mexico "to restore to its splendor the truth, obfuscated by an incredible mob of modern writers on America." He wrote to introduce a more personal (yet still colonial in nature) account of central Mexico, its Indigenous peoples, and its pre-Columbian histories into a festering European intellectual community which was beginning to form more comprehensive standards for citations and therefore the "legitimacy" of knowledge.

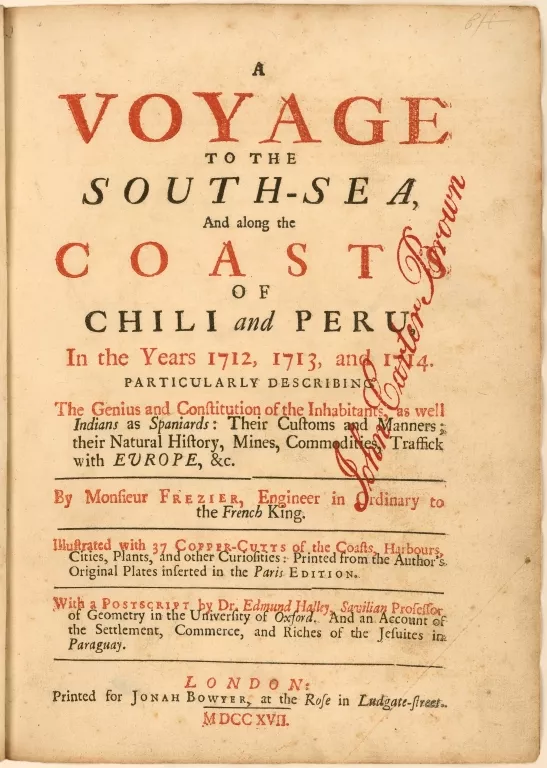

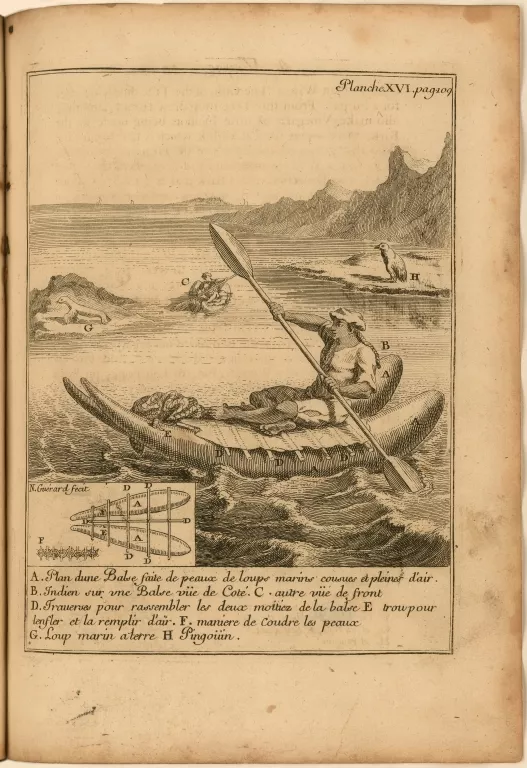

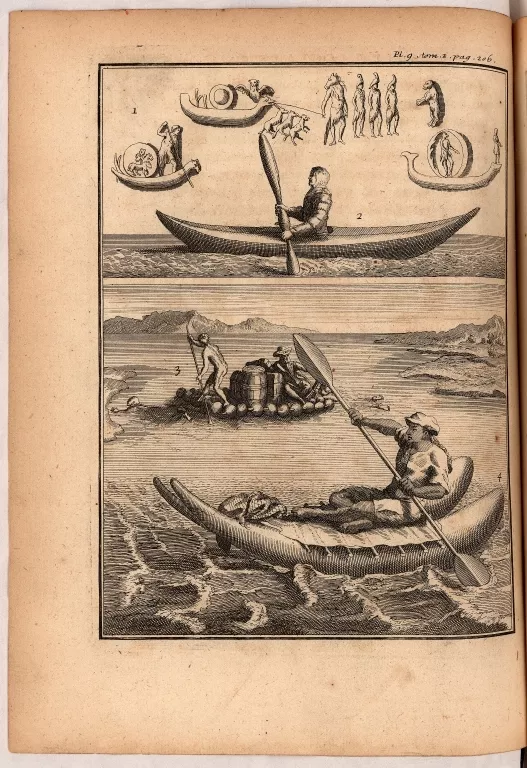

Taking a turn from the Jesuit scholarship above (and going back about 50 years), another Frenchman, Amédée-François Frézier, was tapped by King Louis XIV in the early 18th century for his military expertise, to scope out the geography of Spanish and Indigenous coastal Latin America. He came out with his Voyage to the South Sea (Relation du voyage de la mer du Sud) in 1716. While the original text is in French, the researched version is an English translation of Frézier's original work, published in 1717. Jonah Bowyer, for whom the English print was made, had the book printed for sale in his book shop, the Rose, on Ludgate Street, London. In the postscript of the translated edition, Frézier's peer Edmond Halley commends Jonah Bowyer for undertaking the English translation of the book as he believed that English readers would want to acquaint themselves with the seas and the peoples in the Americas and further inquire “what may be of use.” The English edition is also illustrated with 37 copperplate engravings of the coasts, harbors, cities, plants, and other curiosities printed from Frézier’s original plates (hence their inscriptions are in French). It is specifically noted that Frézier lent his permission for the English publication and that procuring the original plates for the book was rather costly.