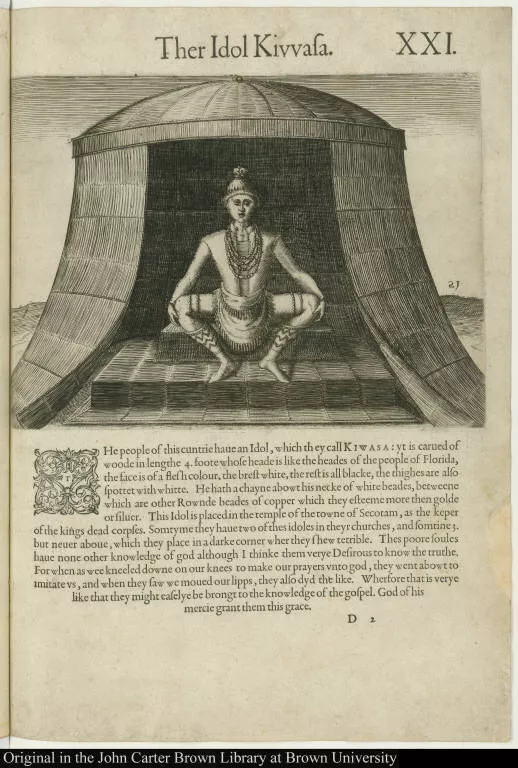

Although the purpose of the report is to introduce Virginian commodities and the local culture, throughout the book, de Bry and Harriot have made striking connections between the Indigenous people and the Europeans. At the start of the volume, an engraving of Adam and Eve was placed alongside with the frontispiece depicting Native Americans, their idol worship, and their flora and fauna. De Bry recognized the similarity between the biblical figures and the Indigenous people in his letter ‘To the Gentle Reader.’ He said that Adam and Eve were banished from Paradise because of their ‘disobedience’; yet, like the people of ‘savage nations’, they showed great self-sufficiency in providing for their own needs.

An even more striking connection between the Virginian people and the Europeans come from the section “Som Pictvre of the Pictes which in the Olde Tyme dyd Habite One Part of the Great Bretainne” attached at the end of the book. At the start of this section, de Bry wrote on the bottom of the page: “The inhabitants of the Great Britain have been in times past as savage as those of Virginia.” This is followed by five pictures accompanied with text by Harriot of the Picts people, who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages.

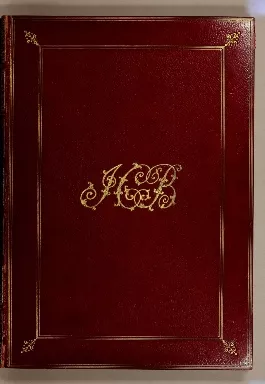

Indeed, the first “true picture” of a Pict man, adapted from a watercolor by John White, looks truly barbaric (see page 113 and 117). Naked and painted from shoulders to ankles with monstrous hybrids of all sorts, he held his arms and brandished an enemy’s head. Located on his chest, belly, shoulders, and knees are grotesque faces whose purpose must have been recognized by early modern viewers as a means of magical protection against enemies. Actually, Harriot had made comments of the Virginians, with whom we are expected to compare with the Picts, that “when they go to battel, they peynt their bodyes in the most terible manner that thei can deuise.” Art historian Michael Gaudio mentioned in his book Engraving the Savage that the grotesque is made primitive as a quality of the savage for the simple reason that the savage mind is itself supposed to be grotesque, that is to say, irrational and invested in the magical rather than in the representational power of the image (79). And so the savage paints his body with terrible faces, imagining that they help him in battle and protect him from his enemies.

One question that emerges is why de Bry and Harriot decided to dedicate a section to these “savage” European rather than Native American people. Since the report is a story told from a European point of view, we turn to the historical context in Europe that sheds light on the mindset of the society where de Bry and Harriot were part of. In early modern Europe, as a revolution in the forms of knowledge and expression took place, new science emerged, new philosophies proliferated, and the New World was discovered, meanwhile ancient and classical knowledge had begun to lose their power and authority. Europeans realized that what they had traditionally revered as antiquity, the age of perfect knowledge at the beginning of a history of degradation, was really the youth of mankind, when the greatest philosophers knew far less than an ordinary modern man or woman (Grafton et al., 4-5).

It is obvious to see that the discovery of the non-European world and the discovery that the European ancients were not wiser than the moderns were indissolubly linked. In the report, by appending portraits of the Picts at the end of the book, de Bry effectively equated the alleged barbarism of the American populations with the Europeans’ own ancestors. It served as a piece of evidence to show that the European human societies, rather than inevitably deteriorating, actually progressed through increasingly sophisticated stages of civilization. The section on the Picts reinforces the idea the modern Europeans were superior to all, including their own ancestors and the Native American people.