An integral part of the European colonial project was an effort to understand and catalog the natural world of the Americas. The late 16th century saw a conscious effort made by colonial powers to collect and publish knowledge of the Americas for a variety of purposes, including commodification of natural resources as well as scientific curiosity. The resulting outpour of literature presented the Americas in a way legible to European readership, often sacrificing accuracy and feeding into European social and political narratives in the process.

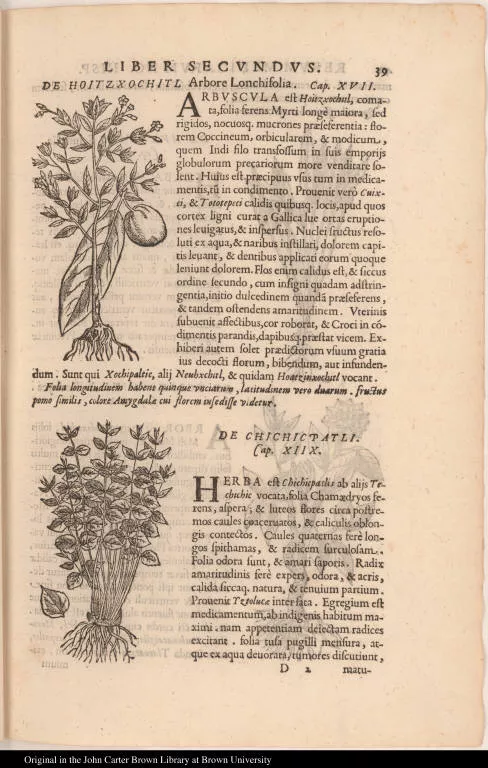

The lavishly-illustrated Nova plantarum, first published in 1651, classified American plants and animals into a western catalog of knowledge. Each species was extracted from its environment, depicted largely independent from its natural context, and paired with its Nahuatl and Latin names followed by a description of the species with particular emphasis on its relevant medicinal uses. These descriptions often included comparisons to similar European species in order to contextualize unfamiliar species for European readership. Organized by taxonomic group, the Nova plantarum presented a conceptualization of American nature designed by and for European scholarship. Even as some Nahuatl was included, Nahuatl names were recorded in the Roman alphabet and were meant to supplement the use of Latin names. While much of the information made its way to publication from Indigenous sources, the Nova plantarum as a whole was not concerned with preserving Indigenous ways of knowing. Rather, it curated Indigenous knowledge for inclusion into Western structures.

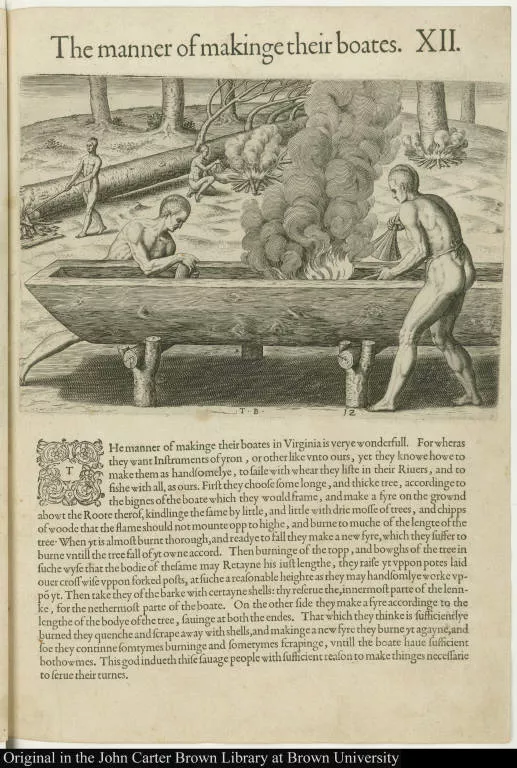

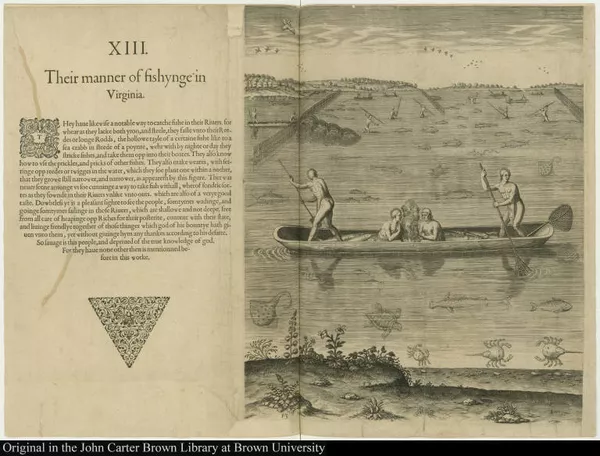

Similarly, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, published in 1590, consistently referenced European plants and animals to aid in describing American species. While not as extensive or methodical as the encyclopedic Nova plantarum, its presentation of the natural world is written from a distinctly European perspective for a distinctly European audience. In contrast to the Nova plantarum, A Briefe and True Report includes more explicit mention of Indigenous communities and their ways of interacting with nature. However, even these practices were presented in contrast to European standards and thus European and Indigenous cultures were conceptualized in opposition to one another.

While European literature on the Americas was driven in part by genuine curiosity and the quest for scientific knowledge, the information gathered by European scholars was also informed by the colonial conquest and exploitation of American resources. Francisco Hernández, whose extensive notes and research of American flora and fauna formed the foundation of the Nova plantarum, was ordered by King Philip II of Spain to find plants of medicinal and economic value. These direct orders from King Philip II formed the basis for knowledge collection and reveal the Nova plantarum's role in the colonial project and its exploitative relationship with Indigenous peoples of Mexico and the natural world. While intellectual curiosity may have driven the creation and publication of the Nova plantarum, the information gathered and eventually published was necessarily informed by this colonial motive.

Similarly, the authorship of A Briefe and True Report and the context of its creation place it within the framework of conquest and exploitation. The book largely concerns itself with selling the adventure of colonialism, advising the reader directly that learning of the natural world of the Americas “may returne you profit and gaine, bee it either by inhabiting & planting or otherwise.” This explicitly establishes colonization as the aim of the book, presenting the natural world as a resource to be exploited for personal economic gain.

The History of Mexico was created under different circumstances. In contrast to the Nova plantarum and A Briefe and True Report, the author of The History of Mexico, Francesco Saverio Clavigero, was born and raised in Mexico, learning Nahuatl at a young age and later teaching Indigenous youth at the Colegio de San Gregorio. These experiences with Indigenous Mexican culture coupled with close study of Aztec codices informed Clavigero’s depiction of the Americas in The History of Mexico, often describing Indigenous people more sympathetically and with greater cultural awareness. Clavigero’s text also includes maps of the Americas using Nahua names and iconography, perhaps indicating a greater understanding and respect for Indigenous peoples. That being said, Clavigero’s role as a Jesuit missionary and scholar situates him within the colonial context. His depictions of the natural world are therefore written with the assumption of European claims to American land and the utilization of American resources by European powers.