Katherine Godfrey, Long Term Fellow Pennsylvania State University

My fellowship period at the JCB was both inspiring and incredible in what feels like countless ways. I had the privilege of crossing paths with brilliant, kind, and genuine people and, of course, had the opportunity to handle material I had only read about, seen images of, or did not even know existed until I walked through the JCB’s heavy front doors. The atmosphere of curiosity and intellectual exchange never faltered and, speaking of doors, there always was a figuratively revolving one where researchers came in and out of the JCB’s sphere. I’m so grateful to have passed through it, for reasons of which I’m delighted to share.

As a historian of early modern Latin America, with specific geographic focus on northern South America and Colombia, the JCB’s collection did not want for material. To support my first book project, tentatively titled “Matrilineal Routes: Indigenous Kinship Networks, Gender, and Mobility in Early Modern Colombia,” I looked at printed and manuscript material relating to the history of the Muisca and other Indigenous ethnic groups of the Northern Andes. Since my first book concerns the experiences of Indigenous women and matrilineal societies in European colonization efforts, at the JCB I cast a wide net to examine primary and secondary sources to help better frame the historical context of the book and issues discussed within it.

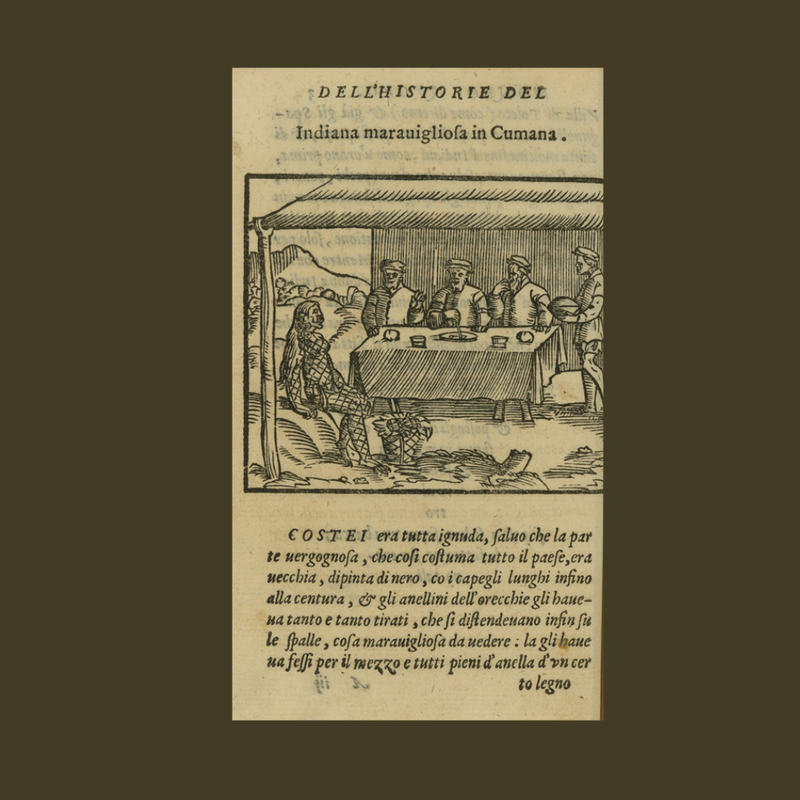

Several sources I consulted in the JCB’s reading room remain an absolute jewel of a memory and have become discussion points within my book manuscript. Three such sources concern the changing representation of an Indigenous Cumaná woman whose image was modified and reprinted several times in European books. Beginning with Benzoni’s 1565 La historia del mondo nuovo and ending with a 1706 Dutch publication that recounted Spanish conquistador Gil González Dávila’s invasion of present-day Honduras, the evolution of the Cumaná woman’s image renders her passive and seemingly unwelcomed to speak before Spanish officials. In other words, what began as an image of a heavily tattooed woman speaking for herself, over the course of roughly 150 years, transformed into someone who appeared to be way more subservient and distressed than previously pictured. I argue that this increasingly accepted practice of subjecting Indigenous women to the sidelines of European history and memory—in this case through image—informs how people largely misunderstand or misinterpret, say, the significance of Muisca women in early colonial society.

Of course, this is just a snapshot of what I contemplated during my JCB fellowship period. I cannot wait to return to this magical space, and of course to the warmth of friends both old and those yet to be made. Furthermore, to be welcomed and assisted by Val, Kim, Genesis, and Mark is a gift in and of itself, and one that I hope every researcher will get to experience at least once in their lives.