Revealing the Viceroyalties: Frézier’s Voyage to the South-Sea

Hydrography and Map Making

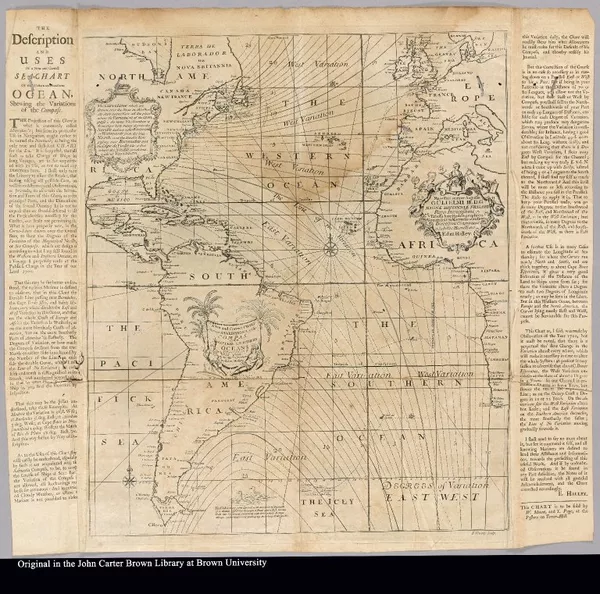

A new and correct chart shewing the variations of the compass in the Wes...

1748

-

p. 1

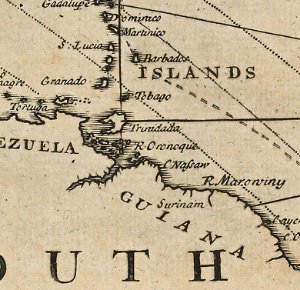

p. 1This map, which was created in 1748 using Sir Edmund Halley's naval charts, displays the location of the Island of Trinidad off the coast of Venezuela with no other major island within leagues of it. This depiction corresponds to Halley's passage on page 320 of the postscript of A Voyage to the South Sea. Halley answers to Frézier's claim that he mistook the Island of Trinidad for the Island of the Ascension in this passage of the text. The English reader is informed by Halley that he had not erred in his cartography and that Frézier had been incorrect in asserting that he had. Halley then asserts that the Island of Trinidad and the Island of the Ascension are actually the same island, as there is no other major island near Trinidad other than the small Isles of Martin Vaz.

Surveillance

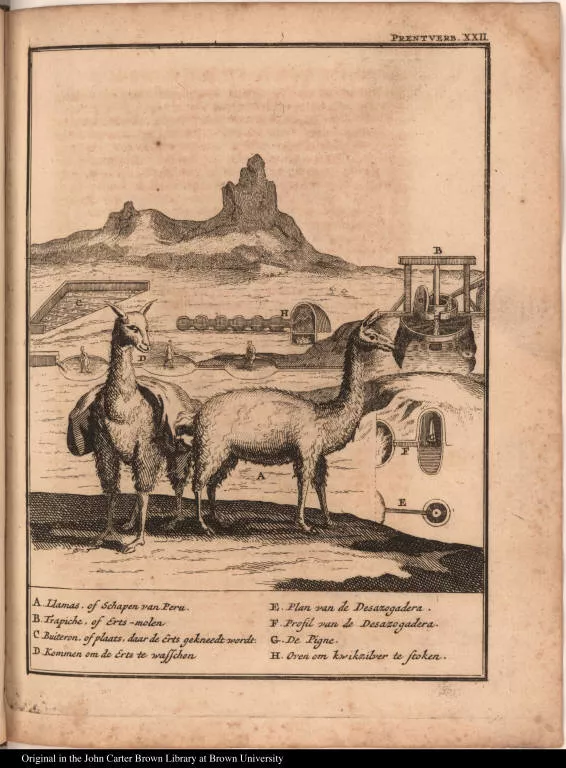

[Mercury processing and llamas]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Three men can be seen wading in a series of pools that appear to be dug into the ground behind two llamas. The liquid that flows around the men’s feet is deposited by an open pipe on the leftmost side of the print, cut off by the print’s border, presumably coming from another refining machine. The men who stand within these dug pools are most likely Indigenous Chilean laborers, tasked with the separation of silver from the ore it was contained in. The Viceregal process of silver refining was often dangerous for the largely Indigenous laborers. Silver ore would be mixed with water and various other chemicals, such as mercury, and would be channeled into patios where laborers would repeatedly step on and rake the silver paste to allow the silver to separate from the mass.

Ethnography and the Indigenous Inhabitants of the Viceroyalties

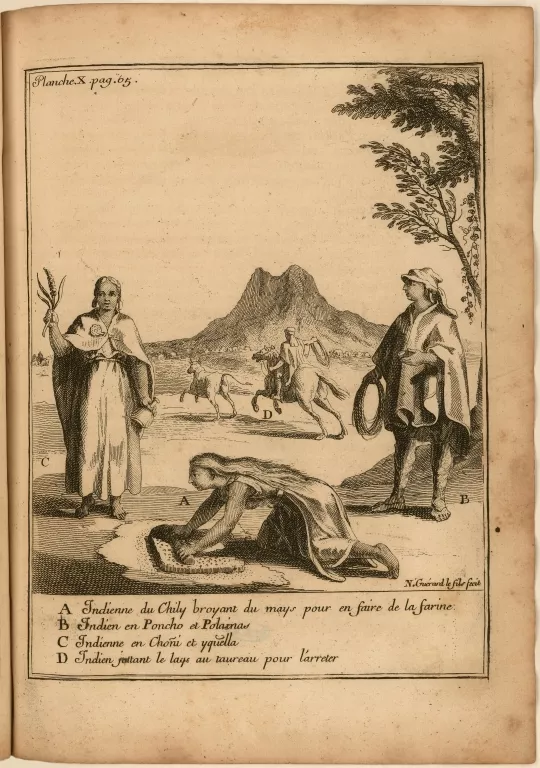

[Native Americans of Chile]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Behind a Chilean woman who grinds corn or maize to make flour and other Indigenous figures, another Chilean man can be seen demonstrating Frézier’s described lasso technique on horseback. He is seen from behind, pursuing a bull; the image’s lettered key claims that the equestrian Chilean intends to “stop” the animal (Frézier, A Voyage to the South Sea, 70). The author makes particular mention of the lasso’s uses outside of herding purposes, noting that during the conquest, the Chileans successfully used nooses to seize control of horses ridden by the Spanish. Frézier’s emphasis on their use against the Spanish is consistent for obvious reasons — the nooses could be used against the Spanish again if the indigenous peoples ally with the French if the French attempt to take over the viceroyalties.

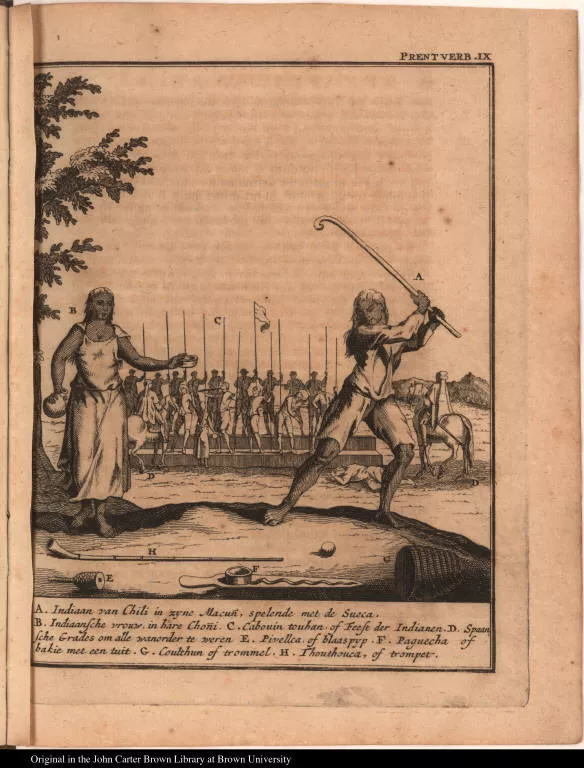

[Native Americans play ball]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Frézier also mentions the hide armor made by the Chileans, as well as the European armor they secured during their skirmishes with the Spanish. In addition to their armaments, Frézier makes mention of the battle formations of the Indigenous Chilean tribes both pre- and post-conquest. Squadrons fight in formation and march in a fierce manner in time with the beat of a drum. Plate IX depicts one of these drums, called a couthun, as object G in the lettered key. A general’s speech always precedes a battle, after which all the men scream and pound their feet to encourage others not to fight them. Additionally, Frézier mentions intimidation tactics being used in conflicts with other tribes and instilling fear in him.

The Spanish Inhabitants of the Viceroyalties

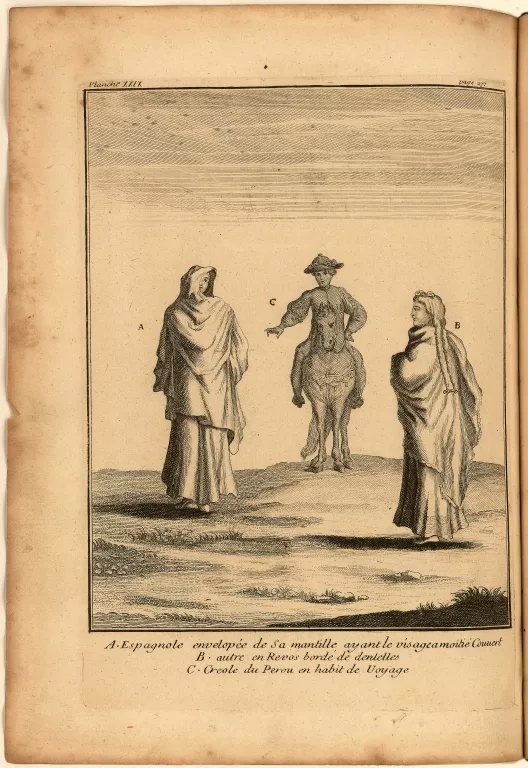

[Women and man on horseback]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Plate XXIX, another print by Nicholas Guerard, is an example of Frézier's critique of the behaviors of the colonial Spanish. In the print, two Spanish women, one with a cloak or mantilla over her head, the other seen from the back, as they presumably walk to the homes of their lovers. A Spanish colonist of Peru is seen on horseback in his traveling garments as he passes between the two women.

-

p. 1

p. 1Accompanying the image was Frézier’s section on the looseness of Spanish women, depicting them walking outside unchaperoned. Frézier observes that the women do not stay at home as much as they do in Spain, preferring to go out. He has no issue with this, only finding it offensive that women frequently walk at night unchaperoned, something regarded as highly unladylike and often done with obscene motivations. The image’s depiction of the woman on the left obscuring her face with her cloak is an allusion to Frézier’s claim that the Spanish adulterers hide their faces as they visit their lovers in the night — it is easy to assume then that the woman hides her face from the man who approaches the pair on horseback, not wanting to be recognized.

Conflicts and Dissent

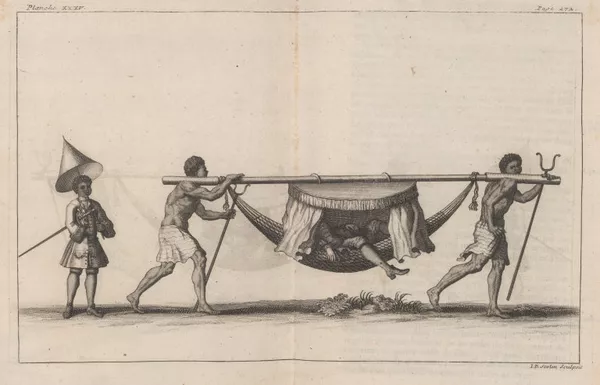

[Two men carry another on a hammock]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1The face of the nobleman is obscured by the cloth overhang of the hammock he lazily resides in, his right hand and foot hanging over the side almost as if to suggest the man is asleep. The two black slaves carry hammock’s support beams and are sparsely dressed, not baring shoes and only wearing loincloths to cover their modesty. The foremost slave’s body contorts as he turns his head to look at the other slave who follows them, his expression simplistic but suggestive of the strain upon his body.

-

p. 1

p. 1The third slave who follows the procession is a young black boy. The boy is dressed unlike his counterparts, with a simplistic knee length coat and boots. He carries his Portuguese master’s sword under his right arm. In his left hand he holds the man’s parasol, presumably for eventual use when the man exits the hammock and wishes to shield himself from the sun. The image’s stressors on the strenuous labors of the slaves whilst their master relaxes outside of the sun’s heat perfectly illustrates Frézier’s disdain for the Portuguese and how they maintain themselves and their colonies.

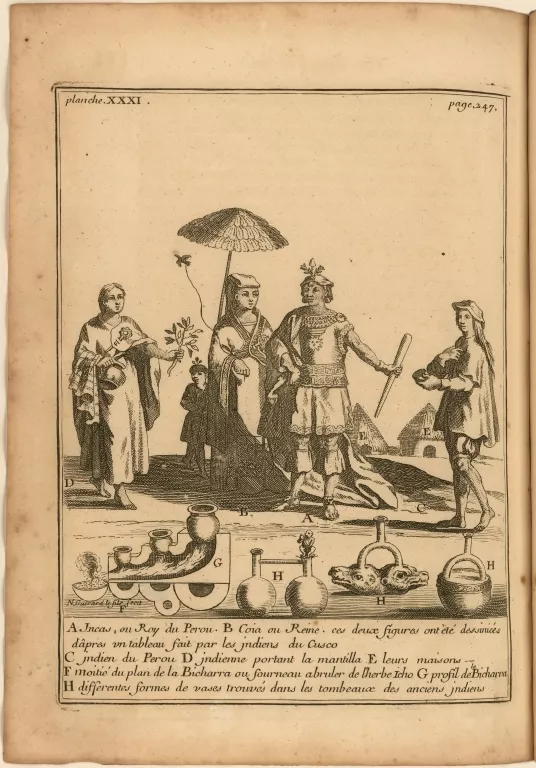

[Inca or Indians of Peru]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Plate XXXI is the image that accompanies Frézier's long section on the people of Lima’s disdain for the Spanish, depicting the Inca chieftain Amapuero and his queen, who possesses a small bird attached to a string. Behind the couple stands a child holding a parasol to shield the queen from the sun.

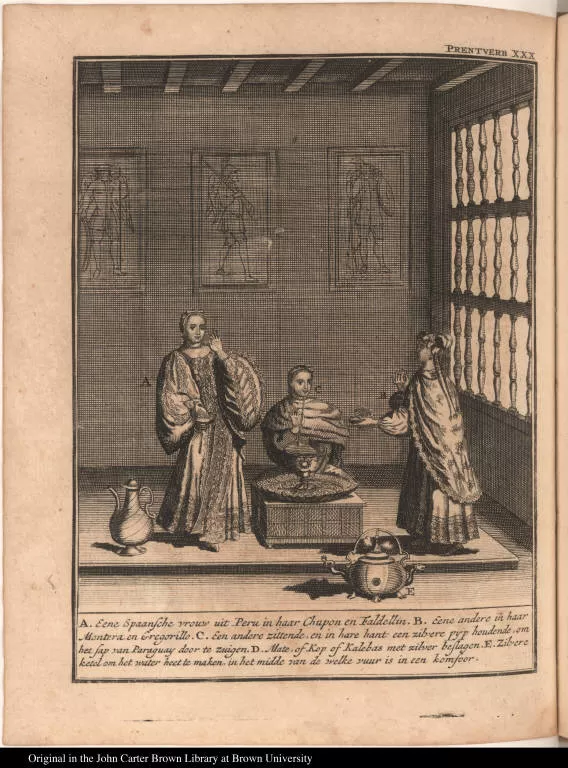

Perceived Value and Consumption of the Volume

[Dress of the women of Peru]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1While Frézier’s provided description for the image focuses on the dress the women wear, identifying their clothing as a chupon, fatdellin, montera, and gregorillo, as well noting the presence of the silver wicker table and teapot or vessels within the home, what is truly of note are the paintings that hang on the wall behind the figures. Beneath the engraved lines of shadow are three separate images of angelic figures dressed and armed as Colonial militiamen. This depiction is not without reason; images of militant angels, particularly Saint Michael defeating Satan, flourished during the period, serving Catholic countries as a powerful counter-reformation image representing the crushing of reformist heretics and, by extension, pre-conquest paganism in the Americas. The image would be further utilized by the Jesuit order when the mendicant friars were chosen by the Spanish to lead a mission in Lima, Peru, in 1568. The order found the invocation of angels helpful in efforts to convert the indigenous community, as Andean religious beliefs espoused tales of winged warriors that served the Inca god Viracocha (Porras, "Going Viral? Maerten de Vos’s St Michael the Archangel", 71). As a result of the archangel’s association with what was already devotional, Jesuit strategies of accommodation in the Andes were made all the easier. Anonymous Indigenous artists trained by the Jesuit mission schools produced many works of the Archangels, typically in scenes of warlike judgment, that proliferated throughout the Viceroyalty soon after the order established itself in the region. The presence of not one but three separate images of these militant angels only further evidences the order’s influences in Lima and beyond.

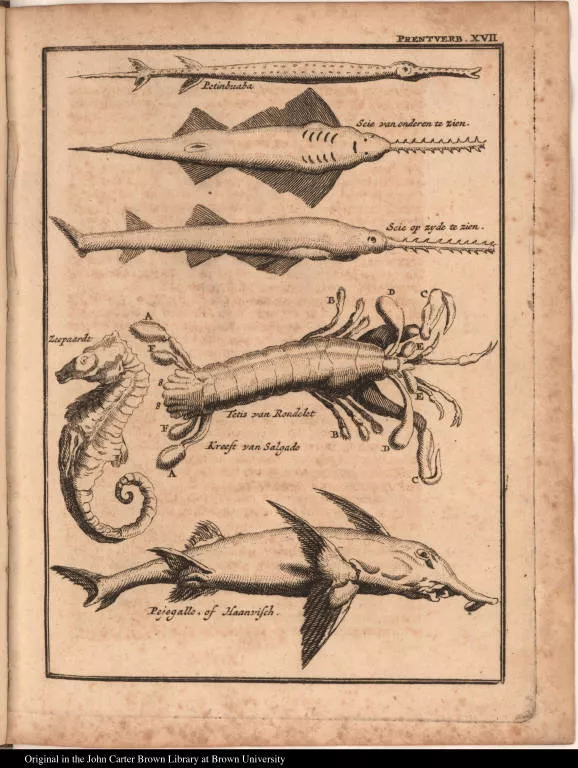

[Fish and sea animals]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1The later use of Frézier’s journal, especially its translations, is evidenced by the 1784 publication of the Pacific voyage notes of Captains Cook, Clerke, and Gore (Griffiths, The Monthly Review). Freziér’s journal is referenced in these notes as the means by which Cook’s men identified the fish they caught as they traveled across the South Sea. Specifically, the notes indicate they largely caught elephant fish, represented in Plate XVII of Freziér’s journal and identified as a pejegallo, the Spanish term for the fish.

Conclusion

Bibliography

Editorial Note

Project Creator(s)

- Rachel Moss

- Michal Loren

- The John Carter Brown Library

- Emily Monty