Empirical Cosmographies and Imaginary Journeys

Americae pars VIII

1625

-

p. 89

p. 89The plate I have chosen chose me while working in the JCB. It is inserted first on page 57 of the travel account of Cavendish, and again on page 79 of Raleigh’s famous account of Guiana, both reprinted in the first issue of the second Frankfurt Latin edition (1625) of De Bry’s Americae Pars VIII. Church’s Catalogue describes the plate in his typically dry style as a “sea-serpent devouring a native in the foreground near boat in which are Englishmen.” But the primal scene of encounter depicted in this plate contains a richly codified discourse of knowledge and empire. Does the sea-serpent here gloss a Protestant, Black Legend reading of the Old Testament prophesy of Daniel, wherein the fourth universal monarchy (Romanic Spain) savagely devours its helpless natives? Does it refer to the prophesy of an Inca return under the auspices of the British, supposedly related to Raleigh by a local cacique? Both? What of the man in the boat, who appears to be addressing us, the readers? Is he the author? What of the native, devoured by the sea-serpent of history? On the reverse page of the first instance of the image we behold another curious plate, this one of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, only this Eden appears to contain imagined American inhabitants. How should we interpret such images of knowledge of and encounter with the New World? Clues are likely to lie in the serpentine intestines of the JCB...

Contributed by Mark Thurner (University of London)

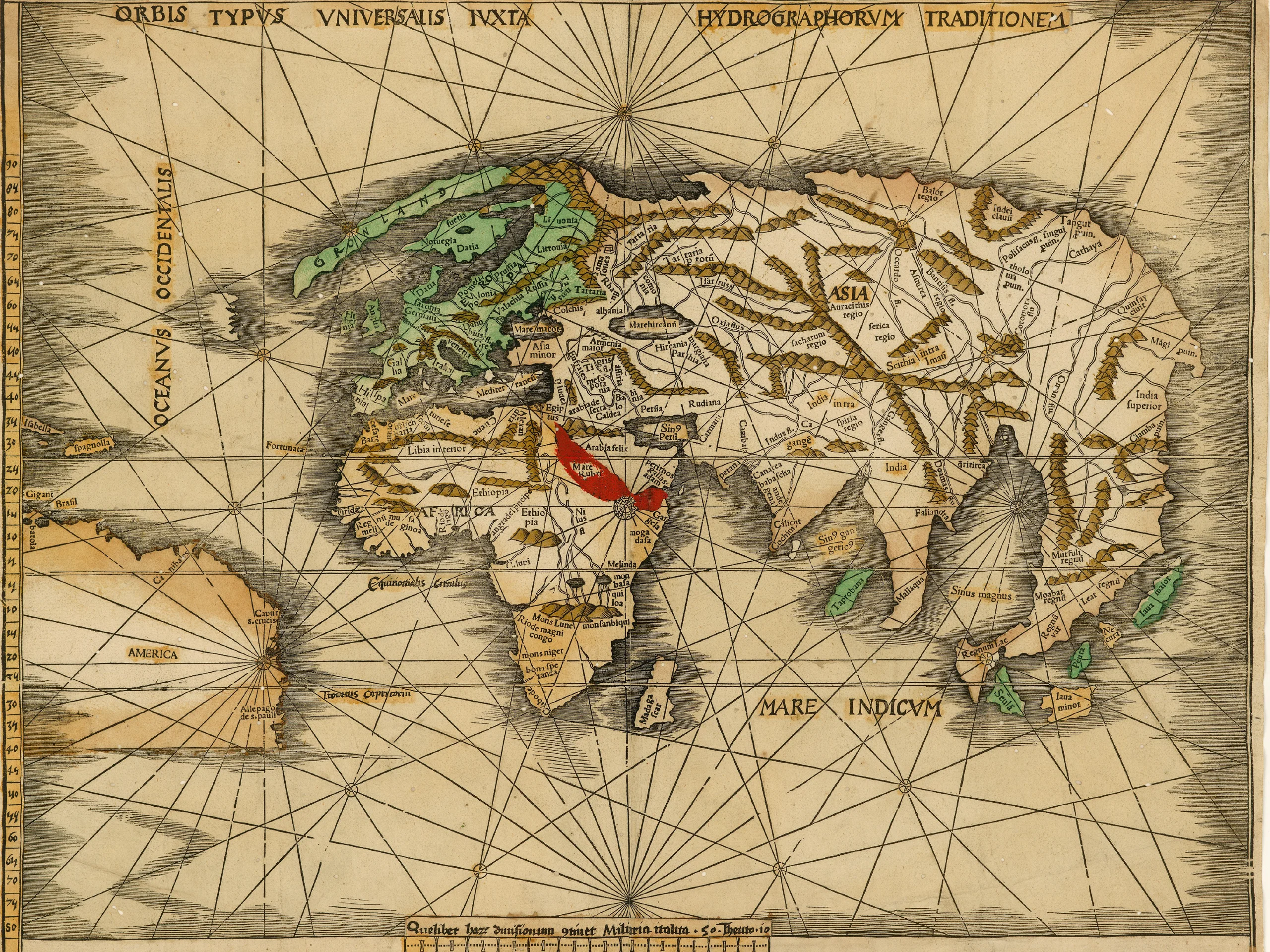

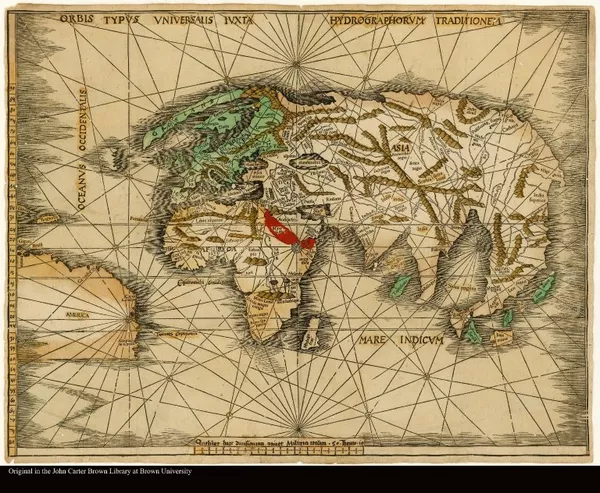

Orbis Typus Universalis Iuxta Hydrographorum Traditionem

1513

-

p. 1

p. 1Este es un mapa lleno de incertidumbres, seguramente una xilografía de prueba para la Geographia de Ptolomeo (1513), una imagen inédita semejante a la que finalmente se publicó. Probablemente fue hecha en Nuremberg por Martin Waldseemüller, el autor del famoso mapa donde apareció por primera vez el topónimo América. O quizás fuera éste. El Nuevo Mundo se vislumbra entre certezas y probabilidades, un continente emergente. Se reconocen con claridad las costas de la Tierra Firme (Spanish Main) y Brasil, y las dos principales islas del Caribe, la Española y parte de Cuba. El mapa es asertivo a la hora de distinguir América de Asia, de la que no forma parte, según se aprecia en su extremo oriental. Quedan las dudas sobre su magnitud y extensión, abruptamente cortada por la escala de latitud a la izquierda. Es un mapamundi ptolemaico con líneas de rumbo como las de las cartas portulanas. Conviven diferentes tradiciones cartográficas, hechos probados e incertidumbres. Está iluminado con colores muy vivos. Se conoce como el mapa de Stevens-Brown, en honor a su primer estudioso, Henry Newton Stevens (1855-1930) y la biblioteca que lo conserva, la John Carter Brown.

Contributed by Juan Pimentel (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas)

Le voyageur philosophe dans un pais inconnu aux habitans de la terre

1761

-

p. 7

p. 7A recent Library acquisition shows that even the most fictional journeys posing as narratives of truth go global at the JCB. Listonai's Le voyageur philosophe dans un pays inconnu aux habitans de la terre (Amsterdam, 1761) recounts a journey that begins at the Falls of Niagara and finishes with a survey of the moon and its principal city Selenopolis, passing through various countries and territories but demonstrating overall how America functioned as a site of symbolic importance in eighteenth-century Europe. The narrator, fascinated by waterfalls, describes the many that he had visited – on the Nile, the Rhine, the Danube, among others – before recognizing the extraordinary North American falls at Niagara as the most impressive of all. Previewing the utility of these cosmopolitan voyages, the narrator emphasized in his preface the multiple goals of the philosophical voyage, a manifesto for the global traveler: “to know our fellow humans, compare the customs of different countries… research the spirit of their laws… [and] distinguish truth from verisimilitude.”

Contributed by Neil Safier (The John Carter Brown Library)

The American military pocket atlas

1776

-

p. 13

p. 13The American Military Pocket Atlas, called the ‘Holster Atlas’ because it was made for the mounted British officer, was published in 1776. The atlas incorporates British, Anglo-American, and Indian knowledge of the theaters of revolutionary war, synthesizing maps by Thomas Pownall, British governor of Massachusetts Bay, and Peter Jefferson. It also makes note of Indian knowledge of terrain that is available to the British only as lacunae: “an old Apalachean Tribe … keep the Avenue secret.” Its format takes military cartography from the library to the battlefield, a function that, as the advertisement notes, has been “much wanted.”

Contributed by Jennifer Reed (Brandeis University)

Joannis Bisselii, è Societate Jesu, Argonauticon Americanorum, sive, hi...

1647

-

p. 9

p. 9Pedro Gobea de Victoria most likely was a fictional character whose life and peregrinations closely resemble those of Bartolomé Lorenzo, a young Portuguese man from the Algarve who sometime in 1570 fled to Peru for obscure reasons. Lorenzo had to endure storms, fight pirates, and lay moribund for months in Panama before he reached the South Seas. Once in the Pacific, he shipwrecked off the coast of Manta. Like Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, Lorenzo became a maroon who walked for some thousand miles through forests and deserts, facing hostile Indians and animals. It took him seven years to complete his trip to Lima. In 1577, Lorenzo joined the order of the Jesuits in Lima as a humble criado. Lorenzo spent nine years doing menial work in silence until the provincial José de Acosta compelled him to describe his life.

Acosta put down in writing Lorenzo’s testimony and submitted it in 1586 to Claudio Acquaviva, the Jesuit superior. Lorenzo’s testimony finally came out in 1666 in Alonso de Andrade’s Varones ilustres en santidad y letras. Yet, in 1610, a heavily retouched, literary version of Lorenzo’s adventures appeared in Seville as Navragio y Peregrinacion De Pedro Gobeo de Vitoria, natural de Sevilla, escrito por el mismo. In 1622, a German abbreviated translation of the mysterious Pedro Gobea of Victoria came out in Ingolstadt as Wunderbarliche vnd seltzame Rai[beta] Deß Jungen vnd Edlen Herrn Petri de Victoria Auß Hispanien in das Königreich Peru. The Jesuit Joannis Bisselli translated the whole of Gobeo’s 1610 original publication into Latin, adding numerous glosses and commentaries of his own, ranging from geography to natural history to analogies from the classics. The book came out in Munich in 1646 as Argonauticon Americanorum, sive, Historiæ periculorum Petri de Victoria, ac sociorum eius, libri XV. The adventures of the manuscripts and editions of the life of Bartolomé Lorenzo-Pedro Gobeo were as involved and global as the peregrinations of the man himself.

Contributed by Jorge Canizares-Esguerra (University of Texas at Austin)

Corporal Geographies

Sitio, naturaleza y propriedades, de la ciudad de Mexico

1618

-

p. 3

p. 3After receiving his training at the University of Alcalá, Diego de Cisneros set up his medical practice in Mexico City in 1612. His Sitio y naturaleza de la Ciudad de México (1618) is a fine example of thinking about climate in the early modern age. It is modeled on the Hippocratic medical tradition, which had described health as an equilibrium between physis, the body, and the circumfusa, the sum of natural elements which surrounded and acted upon the body and included waters, winds, the qualities of the terrain, and above them all, astral influences. To properly diagnose patients, the physician would analyze the natural givens of each place and the way they interacted to determine the temperament of the locale and its people, which is to say, the particular mixture of humors that accounted for the physical and moral make-up of the population. The Hippocratic doctrine served as a sort of proto-human geography, allowing for the enrollment of places and peoples in a grand cosmic plot, in which role it was particularly useful to those European physicians and astrologers who produced and organized knowledge about the New World and its inhabitants. Cisneros’s Hippocratically informed description of Mexico City, lacing first hand observations with references to classical sources, recognizes a certain similitude between Mexicans and the inhabitants of Phasis, as described by Hippocrates. Both peoples lived in a country that was marshy, hot, watery, woody and subject to violent showers. They dwelled in huts made of reeds and wood, went to market in boats down the many canals in their city, and drank waters that were hot and stagnant, corrupted by the sun.

Contributed by Miruna Achim (Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana)

Ensaio dermosographico ou Succinta e systematica descripção das doenças cutaneas

1820

-

p. 49

p. 49The Bouba, a disease of African origin, was extremely common among the slaves that supported the intercontinental traffic in slaves. The indigent Antonio Gomes lived in Brazil on two separate occasions – from 1797 to 1801, and again in1817 – during which time he researched medicinal plants and the health conditions of the city of Rio de Janeiro, where he focused primarily on skin diseases, or skin pathologies, that affected the population in countless manifestations. The skin diseases were considered at that time to be endemic to the hot climate, as well as exclusive to Afro-Brazilians, including the Bouba.

Contributed by Magali Romero Sá (Casa de Oswaldo Cruz)

Summa y recopilacion de cirugia, con un arte para sangrar, y examen de barberos

1595

-

p. 271

p. 271As far as it is known, this image is the first anatomical engraving printed in America. It draws in a schematic way the human intestinal tract, from the stomach to the rectum, also indicating the position of the kidneys, liver and spleen. The image was included in the second edition of the surgical treaty of the Spanish surgeon Alonso López de Hinojosos printed in Mexico in 1595. Hinojosos (Castille, 1535c - Mexico, 1597) worked for fourteen years at the Saint Joseph Hospital, an institution created to confine sick indigenous people in the City of Mexico. There Hinojosos made a series of anatomical dissections, commenting some of its results and considerations in his book.

Contributed by José Pardo-Tomás (Institució Milà i Fontanals-CSIC)

Noticias do que he o achaque do bicho

1707

-

p. 3

p. 3Miguel Dias Pimenta’s Noticias do que he o achaque do bicho is one of the earliest books written in the vernacular about medical practice in Brazil. Dias Pimenta, however, was not a university-trained physician or a surgeon. As such, Noticias is a rare printed example of the type of knowledge that popular and unlearned practitioners produced about the natural world and the human body in the seventeenth century Iberian Atlantic. The book describes in detail the symptoms and treatment of a crippling, and ferociously aggressive group of diseases characterized by bloody diarrhea, high fever, stomach cramps, tenesmus, anal sphincter dilatation, anal and rectum prolapses, and intestinal mucosa and anal ulcers that, as the bicho name suggests, were in many cases graced by the presence of worms, usually flies’ larvae. This affliction, which contemporary physicians said came from Angola and the Mina Coast in West Central and West Africa, was called in Spanish and Portuguese locales mal de culo, maculo, and el bicho, among other suggestive names, and was widespread in Atlantic locales by the late seventeenth century.

Contributed by Pablo F. Gómez (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

Francisco Martinez y compania obligacion--Diego de Tineo y consortes--

1555

-

p. 3

p. 3This exceptional document is the commission to establish a private pharmacy in Lima by Diego de Tineo in 1555. The document lists not only all the materia medica imported for the pharmacy, but also the equipment that was to be installed and the books for pharmacists to use. Perhaps the most interesting information it contains relates to the pharmacy itself which was to be exceptionally well-appointed. A carpenter was instructed to create a ceiling on which were to be painted golden stars and a large sun with golden rays. The boxes used to contain the medicines were to be finely decorated with gilt and in place of labels there were to be paintings of notable historical figures, including one depicting the legend known as “Virgil in a basket. Virgil was regarded as an authority by astrologers and alchemists and was even thought to possess the secret of the Philosopher’s Stone. The use of this image signifies the apothecary’s interest in chemical methods, which were being developed by physicians and pharmacists in Spain but were discouraged by the Inquisition as being close to witchcraft.

Contributed by Linda Newson (University of London)

Beyond Nature and Culture

Quatro libros. De la naturaleza, y virtudes de las plantas, y animales q...

1615

-

p. 367

p. 367Right from the arrival of the first specimens in Europe in 1522 – and brought by members of the Magellan expedition, which had just completed the first circumnavigation of the world – the bird of paradise, native of New Guinea and the Moluccas archipelago, became one of the most sought-after items among naturalists and collectors of curiosities. It was not just the bird’s striking plumage and exotic origins that caused the fuss. Travellers’ accounts, together with the fact that the first preserved specimens to arrive had some parts of their bodies removed, had given rise to the legend that the bird lacked feet and spent its lifetime up in the heavens, in permanent flight – hence the local name manucodiata (“bird of God”). Interestingly, many treatises on New World’s natural history and materia medica discuss this ave paradisea or pájaro celeste, as it came to be known in Spanish. Some authors, like Fernández de Oviedo, refer to specimens that they have actually seen. Others, like Ximénez, use information compiled by other authors: in Ximénez’ case, the materials gathered by Francisco Hernández during his expedition. Importantly, these accounts testify to the bird’s status as a perpetuum mobile, both as a natural wonder in endless flight and as a highly valued commodity in continual circulation and exchange. But these references also bring to light the peripatetic nature of natural and medical knowledge in this period and, as in the case of treatises devoted to the New World, its inclusive world-wide range. It is this large-scale movement of specimens as well as information what turns the bird of paradise – a bird associated primarily with the East Indies – into a fascinating case of “global Americana.”

Contributed by José Ramón Marcaida (University of Cambridge)

-

p. 353

p. 353A fines de junio de 1827, el doctor en medicina Martin Hinrich Carl Lichtenstein (1780-1857), director del Museo de Historia Natural y rector de la Universidad Friedrich-Wilhelm, presentaba en la Academia de Ciencias de Berlín la obra del protomédico Francisco Hernández (1514-1587). Se refería a las noticias sobre los animales cuadrúpedos de la Nueva España realizadas por el médico toledano de Felipe II y publicadas, en el siglo XVII. Lichtenstein explicaba la vigencia de esta obra, a sabiendas que, en la zoología de su siglo, los sistemas de clasificación cambiaban y la avalancha de datos desestabilizaba los nombres y las relaciones entre las especies. No obstante, muchos nombres mexicanos utilizados por Hernández sobrevivían en las obras más modernas y los zoólogos contemporáneos no dudaban en utilizarlos.

Las descripciones antiguas debían ser analizadas filológicamente y, para ello, nadie mejor que su colega Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835), con su conocimiento de las lenguas americanas y del diccionario nahuatl de Fray Alonso de Molina (1571). Lichtenstein trabajó con la versión de Recchi y W. von Humboldt analizó las palabras mexicanas allí reproducidas. Mientras la mayoría creaba problemas etimológicos, uno de los cuadrúpedos se traducía sin discusión: ayotochtli, de “ayotl”, calabaza y “tochli”, conejo. Sin embargo, “ayotl”, también podía significar “tortuga”, como aparecía en el vocabulario de Alonso de Molina y en la versión española de Ximénez, que Lichtenstein lamentaba no haber podido consultar. Allí, el cuarto libro sobre las partes de los animales acomodados para el uso de la medicina, se iniciaba con el ayotochtli, o “conejo con concha de tortuga”, llamado por los españoles armadillo. En la versión latina de Hernández, ayotochtli aparecía como Dasypus cucurbitinus, aceptando la versión vegetal de ayotl y usando para conejo, un nombre griego tomado de Aristóteles y de Plinio.

El nombre Dasypus de la versión de Recchi llevaba, por su parte, a la polémica sobre qué designaba esta palabra griega cuya etimología significaba “patas peludas”, un atributo que se podía aplicar por igual a los conejos y liebres y que aún en el siglo XVIII generaba controversia entre los filólogos y traductores de los textos bíblicos. Y aunque algunos propusieron aplicarlo a los erizos, el significado moderno de dasypus no se resolvía. Contemporáneamente a estas disquisiciones sobre el conocimiento de los antiguos y los descubrimientos de los modernos, Linneo, elegiría el nombre de los controvertidos animales de “pies peludos”, filtrado por los informantes nahuatl y los escritores en latín, para llamar Dasypus al género de los cuadrúpedos con caparazón. Es decir, el ayotochtli –un animal que ningún europeo del siglo XVIII confundiría con las liebres o los conejos del Viejo Mundo- se volvía el candidato ideal para reclamar ese nombre. Linneo cerraba el problema llamando Dasypus a un animal nunca visto por los antiguos, sin aclarar que con ello se consolidaba la traducción al mundo clásico de los conejos de calabaza mexicanos.Contributed by Irina Podgorny (Museo de la Plata)

Diario da viagem que em visita, e correição das povoações da Capitania d...

1825

-

p. 5

p. 5The discovery of a natural creature that could produce a shocking power that could lead to lethargy or even kill caught many naturalists’ attention in the entire world. It was unknown how this animal, the electric eel, could pass his energy though another animal's body. Many tried to explain it, but it was in the Americas that the descriptions of this animal allowed for the conclusion that, in fact, it was an electric power. Along with José Monteiro de Noronha and others, Francisco Xavier Ribeiro de Sampaio tried to explain animal differences between Europe and the New World, providing Benjamin Franklin, John Hunter, La Condamine, John Walsh, and Henry Cavendish a global knowledge that was most certainly pioneered in Americas.

Contributed by Rafael Dias Campos (Universidade Nova de Lisboa)

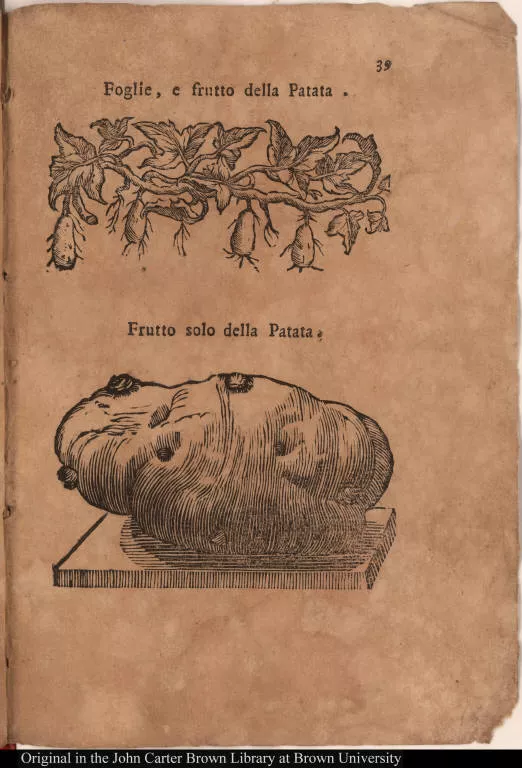

[top] Foglie, e frutto della Patata. [bottom] Frutto solo della Patata.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Potatoes originated in the Andes. For thousands of years they have played a central role in the Andean diet. The rest of the world did not encounter the tuber until Spain’s colonization of the Americas kicked off the ‘Columbian exchange’—the global dissemination of foodstuffs that followed in the wake of 1492. During the Enlightenment, Europeans became interested in the potato’s potential as a cheap, nourishing and reliable staple for the working poor. This eighteenth century Italian pamphlet celebrates the many virtues of the ‘marvellous American fruit commonly known as the potato or earth apple’. Today the world’s most enthusiastic potato-eaters are in the Ukraine and Belarus, and China is the leading producer. We have indigenous farmers from Peru, Chile and Bolivia to thank for potato latkes, French fries, aloo gobi, and many other culinary delights. Andean agricultural knowledge has thus transformed global diets.

Contributed by Rebecca Earle (University of Warwick)

La historia general delas Indias

1535

-

p. 170

p. 170Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo authored the earliest publication dedicated to the natural history of the Americas written by an individual with firsthand experience of the region. This landmark work, Historia general y natural de las Indias (General and Natural History of the Indies, Seville, 1535), fascinated readers with its descriptions of plants, animals, and the landscape, as well as native customs and history. It served for centuries as one of the most consulted and definitive sources on the New World. Oviedo’s chapter on the pineapple transmits the wonder and curiosity that American nature provoked for Europeans at the time, as well as the difficulties of communicating experiences to readers who had never witnessed rare items in person. Oviedo pronounced the pineapple “one of the most beautiful fruits I have seen in all the world in which I have travelled,” praising how it pleased three of the five senses through its “beauty of aspect; sweetness of scent; an excellent taste.” (The sense of touch, he noted, was not similarly rewarded.) Oviedo attempted to capture the sensual pleasures enjoyed by the person lucky enough to encounter such a marvelous fruit in real life, describing its smell as “a mixed scent of quince, peaches, very fine melons and other delightful sensations.” He found the taste more challenging to convey. “It is something so appetizing and sweet,” he wrote, “that in this case words fail me properly to praise the object itself, for none of the other fruits which I have named can in any conceivable way compare to this one.” Words alone, Oviedo acknowledged, could not fully describe the pineapple, making an image a necessary supplement, though not a substitute for personal experience. But print experience was the closest that most Europeans at the time would ever come to the fruit—pineapples, Oviedo admitted, did not travel well.

Contributed by Daniela Bleichmar (University of Southern California)

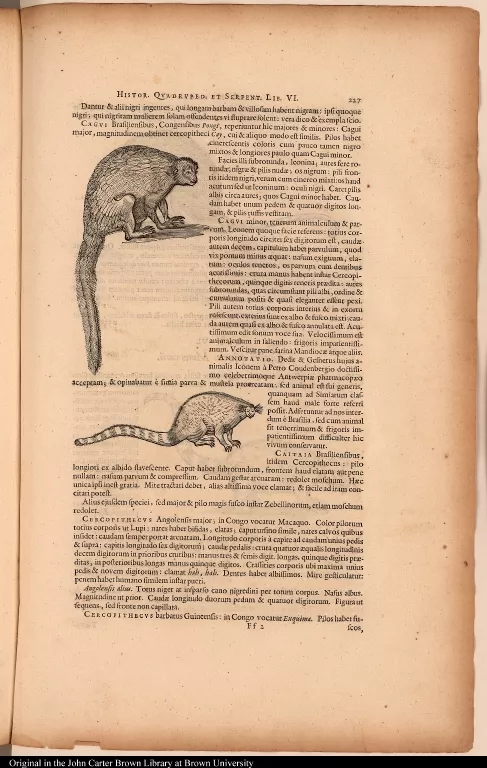

[top] [Cagui Brasiliensibus, Congensibus Pongi.] [bottom] Cagui minor

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1Together with the short-lived German astronomer Georg Markgraf, the Dutch naturalist and physician Willem Piso produced the definitive natural history of early modern Brazil, Historia Naturalis Brasiliae (1648). A striking feature of this text is that it deals not only with flora and fauna native to Brazil, but also with animals and plants known to West Central Africans. The attention that Markgraf and Piso paid to natural knowledge from Angola and the Congo is hinted at in this page from Historia Naturalis, which documents two types of marmosets known to indigenous Brazilians as cagui, but also called pongi “by the Congolese” [Congensibus]. The authors consider the question of whether these odd creatures are the offspring of “a small monkey and a weasel that procreated,” but they conclude that the cagui/pongi is sui generis. So, too, is their book.

Contributed by Ben Breen (University of California, Santa Cruz)

Le Yagouarété D'Az. Le Jaguar. Dessiné d'après nature vivante. Felis Onça Lin.

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Spanish soldier Félix de Azara visited Paraguay in 1782 and spent twenty years studying the region’s fauna. He produced detailed notes on the native animals and birds, many of which were unknown or inaccurately described in existing European texts. This image shows one of the creatures Azara studied, the tamandua, or little anteater, taken from a stuffed specimen in the Parisian Musée d’Histoire Naturelle. Azara’s accompanying notes describe how the insectivore climbs trees to eat bees, emits ‘an unpleasant musky smell’ when irritated, and is called caagüaré in Guaraní, which translates as ‘stinking one of the forest’. Azara also dispels the popular belief that all anteaters are female and mate using their long noses!

Contributed by Helen Cowie (University of York)

Gazeta de literatura de Mexico

-

p. 93

p. 93Can nature be captured in narrative form? This article on New World-endemic hummingbirds by José Antonio Alzate, a criollo polymath and pioneer gazetteer, offered a forceful “it depends”. After numerous “falsehoods” about hummingbirds had circulated since 1492 in European books, Alzate argued that only those natural phenomena that could be observed directly deserved full description. Naturalists should be those who spend their time within nature, not armchair “copyists who write because they read” a book. Alzate then transformed his own decades-long fieldwork in the Americas into a global narrative, peppered with a spirited apology on behalf of Nahuatl nomenclature against the adaptation of the Linnaean binomial system.

Contributed by Iris Montero Sobrevilla (Brown University)

Commerce without Borders

Labyrintho de comercio terrestre y naual

1617

-

p. 5

p. 5The mercantile world was conceived by Juan de Hevia Bolaños to be an autonomous field. The first part of the Cvria Philiphica came out in Lima, in 1603. The second part of the same work was published under the title Labyrintho de comercio terrestre y naval (Lima: Francisco del Canto, 1617). Many editions of the two volumes were published during the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries, transforming Hevia Bolaños’ book into a sort of bestseller of merchant literature. The author was a jurist who went to Peru when he was fourteen years old. The conception of trade as a labyrinth, which could best be decoded through the creation of different typologies and classifications, originated with different types of bankers, merchants, and their agents. Three features of the book are especially revealing. One concerns the presence of African slaves in order to organize different practices of trade around a single commodity. Another concerns the reaffirmation of national boundaries, in spite of the systematic way in which the author pointed out the role of agents, mostly in transactions implying forms of distant trade. Finally, Hevia Bolaños presented a conceptual frame for thinking about merchant and economic activities that is perhaps more accurate than present day attempts to define the same activities at a so-called “structural” level.

Contributed by Diogo Ramada Curto (Universidade Nova de Lisboa)

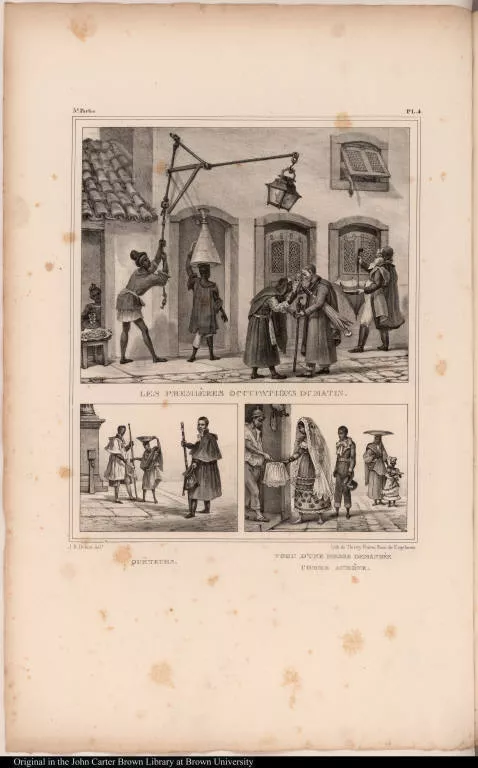

[top] Les Premières Occupations du Matin. [bottom left] Quèteurs. [botto...

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1In this selection, Jean-Baptiste Debret characterizes two types of slaves: hunters and natural history collectors. The hunters supplied the market of exotic animals, as can be observed in the row of colored birds carried by the central character, and the sloth on the shoulders of the third man. The collectors ended up specializing mainly in the collection of plants and insects highly valued by foreigners. The adult man wears a hat with spit butterflies, along with a live snake and an insect box. Without the expertise of those collectors and hunters, the European naturalists would be unable to explore forests and wood paths in Brazil. As such, they represent a level of distinctive expertise that derives from African, as opposed to American, experience.

Contributed by Lorelai Kury (Casa de Oswaldo Cruz)

Report of the secretary of state, on the subject of the cod and whale fisheries

1791

-

p. 21

p. 21A global business off-shores its headquarters. The economy falters. Politicians cry “brain-drain.” Environmental destruction ensues. These presentist concerns fill Jefferson’s 1791 report on the whalefishery. After learning whaling from Native Americans, Nantucketers pioneered a worldwide industry. But independence closed British markets to American merchants, forcing them to seek new shores. Rival empires coveted the revenue and skills this “nursery of seamen” produced. Great Britain lured some to Nova Scotia and Wales, the French recruited others to Dunkirk. Jefferson urged U.S. officials to pass legislation protecting the labor and knowledge forged in New England, launching the “Golden Age” of American whaling.

Contributed by Sarah Crabtree (San Francisco State University)

A letter to Philo Africanus, upon slavery

1788

-

p. 5

p. 5Lord Mansfield’s pivotal ruling in the Somerset v Stewart case (also known as Somerset v Knowles) in 1772 shook the foundation of the British (and later American) institution of slavery, igniting global debates for its abolition as well as for its continuation. A Letter to Philo Africanus, first printed in London in 1786 then reprinted in Newport, Rhode Island in 1788 by Peter Edes, profoundly disagreed with the historical ruling and expounded upon the Divine sanctioning of the British slave trade and its global ramifications if the trade should cease. Additionally, the suggestion of establishing sugar plantations in Africa and China as a recourse would not equal the prosperity of West Indian sugar production, and was therefore thought to be disregarded. The author suggests British slave owners should take a cue from the Portuguese in Brazil, who, he believes, treat their slaves better and are able to produce a greater yield of sugar thus affecting global sugar prices.

Contributed by Sherri Cummings (Brown University)

Traitez nouveaux & curieux du café, du thé et du chocolate

1685

-

p. 334

p. 334El chocolate es un producto que se prepara a partir de semillas fermentadas de cacao (Theobroma cacao). Este grabado combina un dibujo de una rama del árbol de cacao, unos frutos (¿en proceso de fermentación?) y unas vainas de vainilla. La vainilla es el fruto de una orquídea cultivada primero en Centroamerica por los Totonacas. Recientes estudios arqueológicos parecen indicar que el cacao es originario de las estribaciones amazónicas de los Andes ecuatoriales donde la cultura Mayo-Chinchipe la consumía desde 3300 a.C.; y su fermentación y combinación con la vainilla para crear la bebida del chocolate en México y lugares de Centroamérica ya para 2000 a.C. En el grabado, el americano porta una corona de plumas que lo distingue como “americano”, así como con sus instrumentos para preparar el chocolate, bebida estimulante que será tan popular en Europa, como el té de la China y el café de Arabia estudiados por Dufour en este impreso de 1685. Esto nos hace pensar en esa historia conectada de las Americas previa a la colonización española, y luego, en unas conexiones más globales a través del comercio europeo de estos productos estimulantes.

Contributed by Elisa Sevilla (Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador)

Technologies of the Word and the Body

Historia naturalis Brasiliae

1648

-

p. 5

p. 5The Historia Naturalis Brasiliae brings together information about the linguistics, geography, and natural world of Brazil as it was understood and experienced by Europeans, indigenous Tupi peoples, and enslaved Africans in the first half of the seventeenth century. Centered around Brazil, it also contains numerous notes comparing the terminology of in Mexico and the Caribbean. In bringing together these different layers of knowledge, the single-volume tome embodies the intercultural connections that shaped practices of knowledge production in colonial settings across the globe. The book's influence went far beyond Latin America: in 1694, Jacobus Bontius added parts of the HNB to his book on the natural history of Java in the East Indies; and in the second half of the 18th century, a number of copies of the HNB were taken by James Cook and his crew for consultation during their voyages on board the Endeavour.

Contributed by Mariana Françozo (Leiden University)

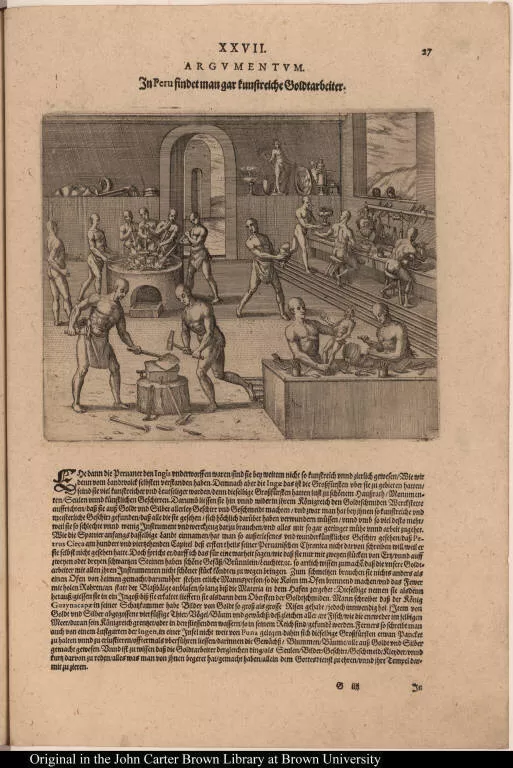

In Peru findet man gar kunstreiche Goldtarbeiter.

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1From 1492, Spaniards used grave-opening as a means of identifying Indigenous peoples’ understandings of the soul, and what riches they possessed. Practices such as interring wealth with the dead were deemed idolatrous, and taken as a justification to loot graves and conquer the people who made them. Nowhere was grave-opening more profitable than in sixteenth-century Peru, where the dispossession of the wealthy and sovereign Inca dead transformed Spanish imperial fortunes. But as representations of wealthy Peruvian graves circulated in the wider Atlantic world—such as in this engraving by Theodor de Bry—grave-opening became a European practice of identifying and looting Native Americans that preceded disciplinary archaeology.

Contributed by Christopher Heaney (Pennsylvania State University)

Directorio espiritual en la lengua española, y quichua general del inga

1650

-

p. 520

p. 520This charming work -- a devotional guide for native Andeans in Spanish and Quechua -- inspired indigenous devotional practices throughout 17th and 18th century Peru. It was the runaway best seller in its day, the only Quechua catechetical work to appear in multiple editions (1641, 1650, 1708), apart from the bishops' officially sanctioned catechism. Directly addressing native parish assistants, it apparently was used for communal devotions among Quechua speaking churchgoers. It concludes with beautiful litanies and hymns in Quechua, including Prado's own meditation on the Passion of Christ. Written in Quechua according to European poetic norms of rhyme and meter, the first stanza runs thus:

Alau Alau Jesusca,

Huaccha cuyac caiñimpim

Cruzpi chacataicusca

Isaci çuap chaupimpi

Alau Alau. (f. 230v)[Ay, ay, Jesus,

Lover of the poor on earth

On the Cross you were crucified

In the middle of two thieves,

Ay, ay.]Contributed by Sabine Hyland (University of St. Andrews)

Relacion de la real tragiocomedia con que los padres de la Compaǹia de ...

1620

-

p. 141

p. 141This play is one of the first performed in Portugal that included indigenous characters. It was written in Latin by the Jesuit Antônio de Souza in order to welcome King Philip III of Spain's visit to Lisbon in 1619 (also known as King Philip II of Portugal). The indigenous characters in the play represented the Portuguese dominions in America, forming the comic portion of the tragicomedy. These are tapuias and aimorés, recognized in the literature as non-speakers of Tupi. However, in the play, in order to create an ethnic identity, they speak Tupi and a modified version of Portuguese. This second language was based on linguistic stereotypes of the speech of black people in the plays of Gil Vicente. What is innovative in this play is the construction of indigenous characters using established language games (Tupi and Portuguese spoken by black theatrical characters), similar to a “language carnival” (Teyssier 2005:582).

Contributed by Candida Barros (Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi)

Historia de las cosas mas notables, ritos y costumbres, del gran reyno d...

1585

-

p. 9

p. 9The JCB houses an original 1585 Rome printing of Historia de las cosas mas notables, ritos y costumbres, del gran reyno dela china by Juan González de Mendoza. It is the essential text for understanding the dissemination of information on China within Europe near the turn of the 17th century. Mendoza became interested in Asia as a young Augustinian in New Spain, where he met friars returning from China via the Spanish route from Manila to Acapulco. Unfortunately for him, his gaze never passed beyond the western shore, and he settled for consolidating and interpreting traveler accounts into a single text.

Contributed by Diego Javier Luis (Brown University)

Dictionaire caraibe-françois

1665

-

p. 23

p. 23What words did Europeans and indigenous people use to the express their relations to each other? Some may not be printable but one certainly is – the French word compere. This entry is in the splendid French-Carib dictionary compiled by a French Dominican priest who had worked in the Caribbean islands in the first part of the seventeenth century. He says that for the Indians compere means my friend and adds the words ibaoüànale, and for women, nitígoan, and some examples of contextual usage. The male term is more frequently and simply written as banaré (also as panawa) and is found all over the Guianas. Breton’s equivalence of friend, banaré and compere reveals the ideal character of trading relations across ethnic frontiers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as peaceful and companionable. Further research though shows these missionaries and traders were misreading a complex indigenous institution based on affinity and ritual exchanges across ethno-political assemblages, which was widespread over the whole continent. Yet their misunderstanding, which must have worked on both sides, permitted people with very different interests to assemble and integrate peacefully strangers into existing relationships.

Contributed by Mark Harris (University of St. Andrews)

Coronica delas Indias. La hystoria general de las Indias agora nueuament...

1547

-

p. 108

p. 108Many people reading this will associate hammocks with leisure and vacations in tropical settings. But the hammock (the word itself is an Arawak loan word) was a significant indigenous technology in use throughout much of tropical Americas at the time Europeans arrived. Made of soft cotton, palm fibers, or other indigenous textiles, hammocks allow for comfortable sleeping in hot weather, protect the person from crawling insects and snakes, and in colder weather, can accommodate a warming fire beneath. In this 1547 book (the first edition was published in 1535) Oviedo wrote about hammocks with ambivalence, pairing them with tobacco as examples of material culture that illustrated his view that Native Americans were strange. But, like Spaniards and creoles throughout the colonial period and into the present, he also revealed himself as a convert. He even thought this was a technology that should go global and envisioned a Europe where hammocks would prevent soldiers’ deaths from freezing and miasmatic conditions.

Contributed by Marcy Norton (University of Pennsylvania)

Credits

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library