Section 1: Self-Fashioning

Tillinghast Family Business Records

-

p. 3

p. 3Seventeen-year old Allin Brown Tillinghast, a member of the Rhode Island merchant family whose business papers are kept at the JCBL, wrote this poem of maritime romance en route to the Caribbean island of Saint Croix in 1796. Powerfully expressive of an adolescent’s sentimental yearning, the poem contrasts the love of a woman with the gold and silver treasure sought by mariners and merchants the world over. This manuscript is particularly poignant because Allin Tillinghast died three months after it was written, on the island of Saint Croix. His elder brother, Captain William Earle Tillinghast, continued to use the notebook for his own business accounts, throwing the poem’s narrative contrast between human passion and economic gain into even greater relief.

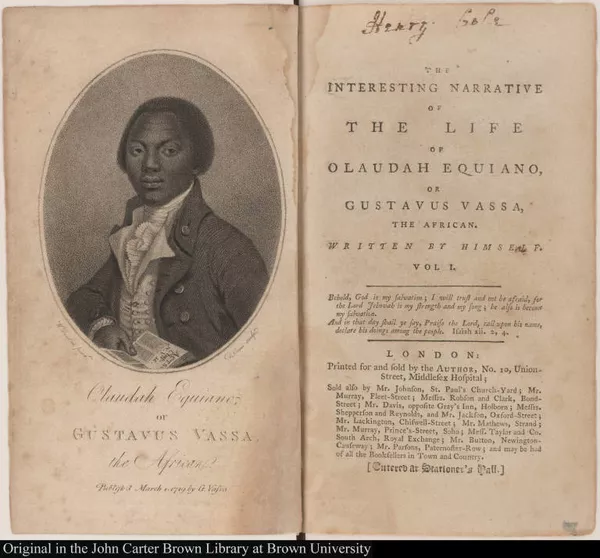

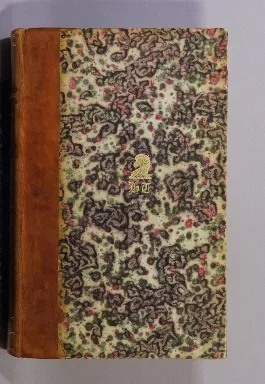

Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Olaudah Equiano’s autobiography presented his life as an African man kidnapped at an early age, enslaved, and ultimately released, and offered to English-speaking audiences a radically authentic perspective on the institution of plantation slavery that was the foundation of European wealth in the Americas.

-

p. 1

p. 1This book popularized the emerging literary genre of the slave narrative, leading the way for the upsurge in such publications in the nineteenth century. Both Equiano’s writing project and its publication were supported by important figures from the British abolitionist establishment who saw in its Christian vision a potential tool for political action against slavery.

The seaman's narrative

1796

-

p. 7

p. 7William Spavens published his account of his life at sea three decades after he was permanently disabled following an accident in his late twenties. He had served in a variety of roles (cook, ordinary seaman, supernumerary) for over a decade in the mid-eighteenth century, sailing from the Baltic to the West Indies to Batavia.

-

p. 7

p. 7Because of his disability, Spavens became impoverished and his account was published by charity subscription in an effort to improve his prospects. With no obvious overstatements that have been identified, his account remains an uncommon glimpse into the everyday life of an ordinary sailor.

Section 2: Learning the Sea, Learning to Sail in Print and in Manuscript

Les arts de l'homme d'épée, ou Le dictionnaire du gentilhomme

1680

-

p. 5

p. 5In this manual dedicated to the Dauphin, the son of Louis XIV, Guillet de Saint-Georges directs his attention to the activities appropriate to the highest rank of French nobility - the noblesse d’épée. The fitting pursuits of this rank of nobleman, he asserts, are threefold: riding horses, learning to serve as military officers, and learning the art of navigation. That navigation should figure amongst the occupations of highest ranking noblemen of the Ancien régime was a recent phenomenon due to the powerful influence of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the Secretary of State of the French Navy, on the culture of politics. By the late 1670s when the first edition of this manual was published, Colbert’s indefatigable efforts had expanded the spheres of activity of both France’s Navy and the French naval culture more generally.

Six dialogues about sea-services. Between an high-admiral and a captain at sea

1685

-

p. 5

p. 5Like Guillet de Saint-Georges, Nathaniel Butler [Boteler] has his sights firmly on the officer class in this publication which is structured as a dialogue between an admiral and a ship’s captain. Butler had been an English privateer in the early seventeenth century before being appointed to the Somers Isles (Bermuda) Company in 1622 by the Earl of Warwick, ultimately serving as the Governor of Bermuda after serving in naval expeditions ranging from Virginia to Cadiz. The six dialogues that comprise this manual discuss the practicalities of managing a ship, including how to outfit a vessel, how to manage a crew, and how to administer a ship and groups of ships in naval action, revealing with particular clarity the weighty responsibilities implicit in the naval hierarchy.

De la navigation

1671

-

p. 5

p. 5This extraordinary navigational handbook attests to the fact that naval manuals could be manuscript as well as printed.

-

p. 43

p. 43Dated to the same period as Guillet de Saint-Georges’ printed manual to the left [see previous item], this volume is a detailed explanation of the science of navigation as it existed in the wake of Colbert’s modernizing reforms which so stimulated French naval activity in the second half of the seventeenth century.

-

p. 101

p. 101It includes sections on latitude at sea and navigation with a compass, with detailed explanations of navigation using trigonometric methods. It is above all exceptional for the volume and high quality of its decoration and illustration, leading to unanswerable questions about the intentions of its author: is it the prototype for a manual intended to be printed? Or was it intended to be a gift to a member of the naval elite?

Traité de navigation

1758

-

p. 9

p. 9This second manuscript naval manual is less mysterious than its predecessor. Its French author, Jacques de Valiariel, signed and dated his work and specified that it was produced in the English city of Carlisle. It too provided a synthesis of current navigational science, accompanied by graphic material.

-

p. 179

p. 179While the quality of illustration cannot match the anonymous 1671 manual, Valiariel drew several detailed maps, including this detailed map of the Atlantic Ocean and its coastal regions, illustrating perhaps his own itinerary. It is possible that Valiariel produced this manuscript in Carlisle as a French prisoner of the Seven Years War, then in its early years. Producing such works was a common undertaking for imprisoned mariners with considerable amounts of time on their hands.

Regimiento de nauegacion q[ue] mando haser el rei nuestro señor por orde...

1606

-

p. 188

p. 188The author of this printed Spanish naval manual, Andrés García de Céspedes, was a learned and influential mathematician and engineer. He wrote this treatise on navigational science to aid pilots and navigators on the Spanish fleets crossing the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in the early seventeenth century. One early reader, however, violently disagreed with Cespedes’ science, adding his own annotations in the margins and crossing out this section on the effects of atmospheric refraction on the establishment of celestial coordinates with such energy that he almost ripped the paper.

-

p. 189

p. 189Navigational science, then as now, was not settled, and the ownership of a manual could mean contesting its contents as well as learning from them.

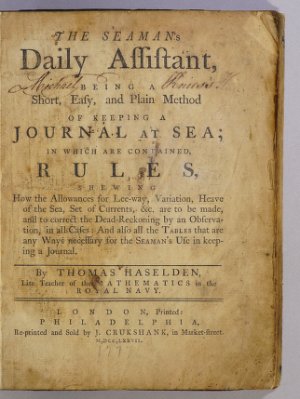

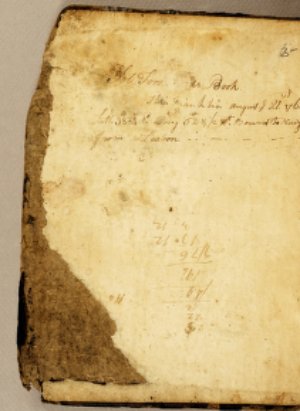

The seaman's daily assistant

1777

-

p. 3

p. 3Printed manuals for ordinary sailors began to be produced and sold in significant numbers in the English-speaking world during the 1750s, and due to the constantly evolving state of navigational information, editions of these manuals soon multiplied.

The seaman's daily assistant

1761

-

p. 2

p. 2Here are multiple editions of the most popular mid-eighteenth century manuals that instructed mariners in daily skills ranging from calculating ships’ position at sea through dead reckoning to keeping a daily log.

The seaman's daily assistant

1770

-

p. 5

p. 5Bound in sailcloth for safekeeping and bearing the intimate marks of multiple owners, these manuals—and their inscriptions—are evidence of the value they possessed for those like Benjamin Greene, Thomas Clark, Seth Worth and Moses Curtis...

The seaman's complete daily assistant and new mariner's compass: being a...

1796

-

p. 3

p. 3... who carried them around the world for decades after their publication.

Section 3: Victualling and Storage

Lyste van de victualien, en ordre op de rantsoenen

1758

-

p. 7

p. 7From the earliest years of their formation, European navies developed systems for the provision of food and drink for the officers and crew who manned the vessels for the duration of their time at sea and while in port. Chartered in 1602, the Dutch East India was an amalgam of private and public interests, but followed common naval protocols in the provision of food during the long trips to Asia, and to the Americas in later decades. The lists of victuals and the approved manner of their distribution and preparation on board ship had been published since 1680 and updated regularly, in efforts to stave off the inevitable health crises suffered by naval crews and caused by inadequate quantities of fresh food and water.

Réponse d'un chirurgien au Second mémoire

1776

-

p. 1

p. 1One French doctor, highly placed in the French naval bureaucracy, devised an innovative solution to the ongoing calamity of scurvy, the deficiency disease that had decimated European mariners for centuries. Antoine Poissonnier-Desperrières proposed an entirely vegetarian diet for naval crews, arguing that the salt beef that formed the core of the French naval ration caused the disease! Because of his political power, Poissonnier-Desperrières succeeded in imposing his vegetarian ration on a few long haul expeditions, prompting a vociferous and scandalized reaction from other naval doctors, including this horrified anonymous response from “un Chirurgien” [a surgeon].

The state of the navy consider'd in relation to the victualling, particu...

1699

-

p. 3

p. 3The thoughts of ordinary seamen about the food imposed upon them at sea were rarely captured in print. However this extraordinary pamphlet - published here in its second edition - was clearly considered saleable by one London publisher at the end of the seventeenth century. In it, an anonymous sailor deplores the mismanagement of the victualling contracts that supplied foodstuffs to the Royal Navy, arguing that “Sailors [were] fed with the Refuse of the Markets” and that the English ships in the Mediterranean should “go by the Name of the Vinegar Fleet by reason of the foul Wines they drank.”

Moyens de conserver la santé aux equipages des vaisseaux

1759

-

p. 243

p. 243France’s premier man of science in the eighteenth century, Duhamel du Monceau, weighed in on the debates over the health of mariners which had such far reaching impacts on the ability of France to effectively wage the global wars of empire that convulsed that century. In addition to designing a new apparatus to clean the fetid air below ship decks, he proposed reforms to the naval diet, going as far as including in this volume recipes for pilaf ‘in the Oriental style,’ German sauerkraut, and epinette, a beverage made from pine trees. This plate illustrates Duhamel du Monceau’s guillotine-like contraption for the rapid slicing of cabbages on board vessels, complete with cabbage.

Arrimage des vaisseaux

1789

-

p. 7

p. 7Given the increase in the size of navies and the number of global naval engagements - in the context of ships’ limited space and the quantity of provisions needing to be stocked on vessels preparing for long naval expeditions - the art of stowage became a nautical science in its own right in the eighteenth century.

-

p. 167

p. 167The four plates that accompanied this manual devoted to stowage illustrate the complexity of the task of embarking and storing hundreds of barrels of provisions such as ships’ biscuit, olive oil, salt, butter, salt cod, cheese, salted meats, wine, vinegar, water, brandy that we see here, in addition to such necessities as cordage, coal, and fuel oil.

Nautical routine and stowage

1849

-

p. 9

p. 9John McLeod Murphy served the United States Navy during the Mexican-American war as a midshipman (the lowest rank of officer) at the age of nineteen. After the war’s end, Murphy wrote this volume based on his experience at sea, declaring in the preface that it was the ‘first methodized treatise [on stowage] ever presented in book form.’ Although this is demonstrably not the case, Murphy’s book most certainly was of more use to the US Navy than earlier British or French books would have been. His updates were limited, however - even though the US Navy had been experimenting with steam for decades by Murphy’s time (formally shifting to steam-powered battleships in the 1890s), his book treats only the intricacies of stowage on ships of sail, such as frigates, brigs, sloops, and schooners.

Section 4: Perspective and Projection

Brown Family Business Records

-

p. 59

p. 59Log book, Ship Ann and Hope, “A journal of a voyage to Canton and return by way of Australia. 1798 – 1799,” Brown Family Business Records

The coastal profile view is one of the earliest cartographic genres to move from manuscript to print during the sixteenth century, first in the Netherlands and then throughout Europe. These early printed pilot guides primarily consisted of rudimentary coastal profile views interspersed with textual sailing directions, before marine atlases developed as their own genre. Manuscript coastal profile views remained (and remain still) a compelling way of depicting coastal formations while located at sea, however, to which this log book attests. The Ann and Hope made five voyages for the Providence-based partnership of Brown and Ives, including the trip to China documented here, and this log book contains many perspectives of the coasts viewed along the way.

Plano y descripcion, Del Puerto del Guarico questa en la Ysla Española ...

1736

-

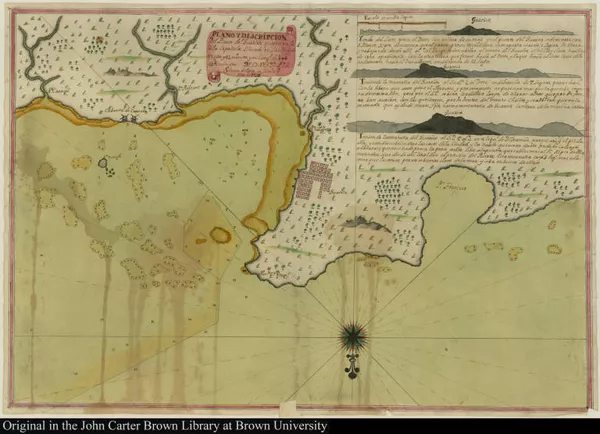

p. 1

p. 1This manuscript chart of the northern coast of Hispaniola was made by Spanish mapmaker and ship captain Simon de Evía, focusing on the port named ‘el puerto de Guarico’ in the cartouche. The toponyms ‘Nue. co. fran.’ and ‘Po Franzes’ point to the name by which it was better known, however, i.e. Cap Français, in the French colony of Saint Domingue. Indeed, the chart shows the embryonic grid pattern of the city that would later become the wealthiest commercial center in France’s Atlantic empire.

-

p. 1

p. 1Nevertheless, in demarcating anchorages, soundings, and sand shoals, and drawing an elaborately decorated compass rose, de Evía presents a ship-board view of the port, not an urban plan.

-

p. 1

p. 1Three inset coastal profiles of ‘el montaña Guarico’ underline its obvious maritime purposes. This elusive view of the French port and its mountainous setting featuring the Indigenous name ‘Guarico’ that the Spanish had always used was almost certainly connected to trans-imperial smuggling with the nearby Spanish colony of Santo Domingo.

Mountserrat Island 1673.

1673

-

p. 1

p. 1This 1673 manuscript map was one of the first William Blathwayt collected when he began his post as Assistant Secretary of the Committee of the Lords of Trade and Plantations in 1675. The map is visually unconventional, representing the coastlines of Montserrat as a series of coastal views, each joined to the next to approximate the shape of the island. The map’s unusual form foregrounds two crucial elements of the seventeenth century mapping of the Caribbean: first, how utterly unknown island interiors were in this period and...

-

p. 1

p. 1second, how the coastal profile view relied on the emplacement of the observer at a precise distance from land. Without this fundamentally embodied perspective, the representation of land could not be rendered in a way that would make the physical features on the map recognizable at sea.

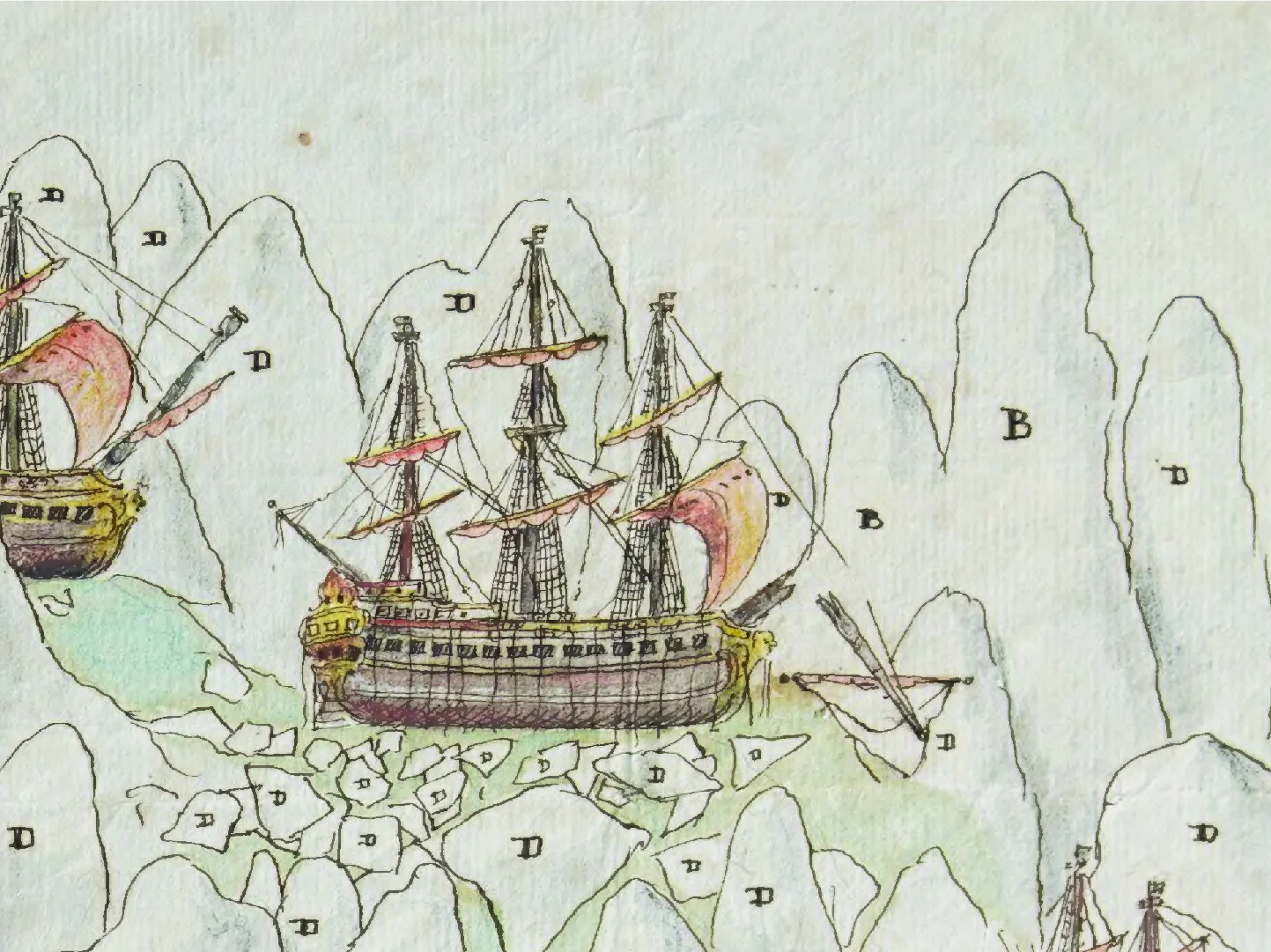

La corveta Atrevida entre bancas de nieve la noche del 28. enero de 1794...

1798

-

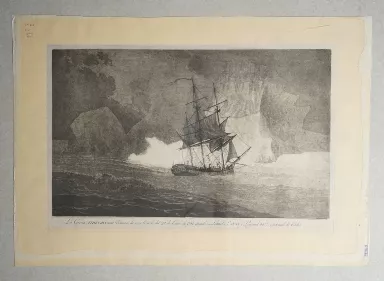

p. 1

p. 1Land was not the only physical feature that maritime crews and passengers sought to represent in eye-witness renderings. Alejandro Malaspina and José de Bustamente y Guerra led a five-year scientific expedition (1789-1794) sponsored by the Spanish Crown in two frigates that sailed the west coasts of the Americas and crossed the Pacific Ocean. The fearsome rounding of Cape Horn involved navigating through fields of the enormous ice floes that are captured in this engraving by Fernando Brambila, one the expedition’s artists on board the Atrevida. Brambila portrayed the passage and its dangers in classic heroic style, showing the ship and its men dwarfed by the looming ice.

La fregata nombrada la Ventura

1770

-

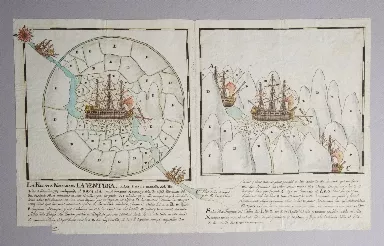

p. 1

p. 1The Spanish merchant vessel La Ventura had successfully made the same hazardous ice-plagued journey around Cape Horn five times prior to the voyage represented in this distinctive drawing, each time with the particularly rich cargo of precious metals, cinchona bark and cacao that made the risk worth the investment. The drawing’s legend recounts how, on October 8, 1769, the vessel encountered a ‘mountainous range’ of ice floes and had to pick its way through them to safety. In the drawing, the author ‘maps’ these floes using letters explained in the key, ingeniously depicting the ship’s progress through the range of ice floes by combining a range of perspectives rarely employed on more formal maps.

Section 5: Birth and Death

Résumé du témoignage donné devant un comité de la Chambre des communes d...

1814

-

p. 5

p. 5Abolitionist Thomas Clarkson’ history of the anti-slavery movement in Britain was first published in 1808, the year after the passage of Britain’s Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, appearing subsequently in many translations.

-

p. 8

p. 8The image was a powerful piece of visual rhetoric employed by the anti-slavery movement in various graphic forms for decades. This French translation of Clarkson’s history was issued with a re-engraving of the Brookes. The artist and engraver chose to include a startling and disturbing detail not present in the original Brookes engraving - the figure of a captive woman giving birth in the ship’s hold, assisted by another captive. As pregnant African women were indeed kidnapped - and women were raped during transatlantic crossings, resulting in pregnancies - birth in this manner was certainly an historical occurrence. This harrowing representation of birth reminds all viewers of the intrinsic racial violence of seagoing life–and its representation–in the age of transatlantic slavery.

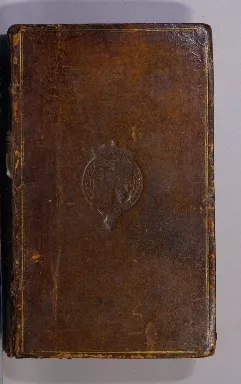

The English pilot. The fourth book

1745

-

p. 9

p. 9The first ambitious marine atlas project undertaken in England was begun in 1671 by John Seller, a prominent London cartographer, in a period dominated by Dutch chart- and map-making. It was entitled The English Pilot, and was published in different “books” that corresponded to different world regions. The pilot contained a combination of newly drawn and engraved charts and those copied from Dutch and French originals. The JCBL collections contain many editions of The English Pilot, Fourth Book, which was devoted to navigation “from Hudson’s Bay to the Amazon” that came to the Library from John Carter Brown’s seafaring family.

-

p. 153

p. 153Containing scraps of the original eighteenth-century burlap that had covered it and marked with the sealing wax that bound the burlap to the covers, this copy of the 1745 pilot was used at sea by Captain James Brown, the eldest great-uncle of John Carter Brown.

-

p. 152

p. 152Indeed, coming full circle, the pilot memorializes James Brown’s death at sea—an all too familiar maritime experience—at the age of 25, in a succinct note inscribed on the endpaper: “York in Virginia, February 15, 1750, Capt James Brown died half an hour past 6 ½ at Nite.”

Section 6: Risk and Opportunity at Sea

The narrative of the honourable John Byron

1768

-

p. 9

p. 9This account of the 1741 shipwreck of the HMS Wager and subsequent events underlines the omnipresence of risk at sea in many of its potential manifestations. Lost from the squadron led by George Anson after a disastrous rounding of Cape Horn, the Wager foundered on an island off the coast of Chili, where the surviving crew were marooned. The strict shipboard social hierarchy soon collapsed, leading to mutinies, separate desperate return voyages to Great Britain, court martials, and the emergence of conflicting and antagonistic narratives of the entire misadventure, including this one by midshipman John Byron.

A new account of some parts of Guinea, and the slave-trade

1734

-

p. 7

p. 7An avid and experienced slave trader from the early eighteenth century, William Snelgrave used his printed account of his 1719 capture by pirates to defend the burgeoning British trade in human beings, dedicating the work “To the Merchants of London trading to the Coast of Guinea.”

-

p. 209

p. 209The danger and volatility inherent in the trade’s dehumanizing of African prisoners is forcefully revealed in this passage recounting one of the countless shipboard insurrections led by Africans against their British captors. It exposes the inability of the British to understand the actions of African people in all of their linguistic and ethnic diversity, to distinguish amongst them, and to control them.

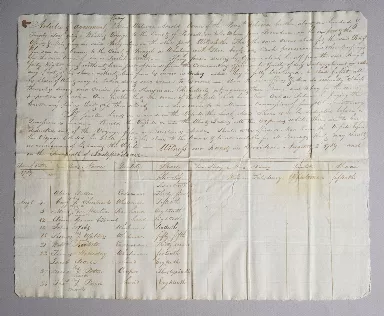

Arnold Family Business Records

-

p. 2

p. 2Portage bill, Brigantine Rebecca, August 1789, Arnold Family Business Records

The sea, and the constant need for labor aboard sailing ships, also could also offer opportunities for African-descended men otherwise constricted by bonds of servitude. An enslaved Rhode Islander, Mint Martin, voluntarily signed on as a ‘raw hand’ to the brig Rebecca, a ship belonging to Welcome Arnold, to join a whaling voyage bound for Brazil in August 1789. While the Rebecca’s portage bill shows Mint Martin’s wages (an eighteenth share of the cargo), there is no mention of his race or of his civil status.

-

p. 2

p. 2Portage bill, Brigantine Rebecca, August 1789, Arnold Family Business Records

The sea, and the constant need for labor aboard sailing ships, also could also offer opportunities for African-descended men otherwise constricted by bonds of servitude. An enslaved Rhode Islander, Mint Martin, voluntarily signed on as a ‘raw hand’ to the brig Rebecca, a ship belonging to Welcome Arnold, to join a whaling voyage bound for Brazil in August 1789. While the Rebecca’s portage bill shows Mint Martin’s wages (an eighteenth share of the cargo), there is no mention of his race or of his civil status.

Arnold Family Business Records

-

p. 1

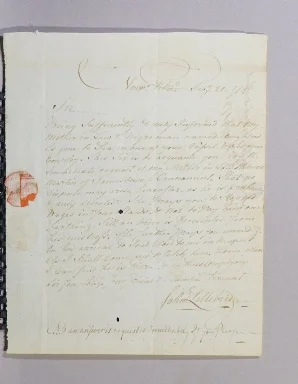

p. 1John Lillibridge to Welcome Arnold, 1790 February 21, Newport, Rhode Island, Arnold Family Business Records

In a letter to Welcome Arnold written six months later, however, John Lillibridge condemns Mint Martin’s disappearance on behalf of his mother-in-law Rebecca Martin, Mint Martin’s enslaver, who learned that Mint had ‘gone to sea.’ Rebecca Arnold was now seeking both to re-enslave Mint Martin and to take possession of his wages from his labor aboard the Rebecca.

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library