During the migration of our legacy catalogs and past exhibitions into Americana, there are occasionally items that cannot be immediately included in our new environment. This may happen for two reasons: the item in question is not yet cataloged, or it was lent by another institution.

Any items that are not integrated into Americana are included in this section and added to our processing queue.

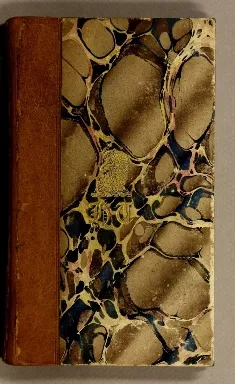

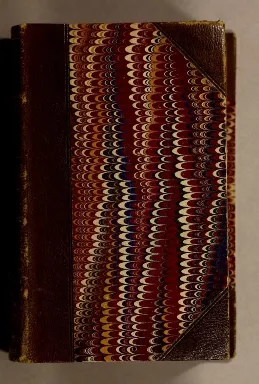

27

Manasseh Ben Joseph Ben Israel

Esperança de Israel

Amsterdam: Semuel ben Israel Soreiro, 5410

[i.e., 1650]

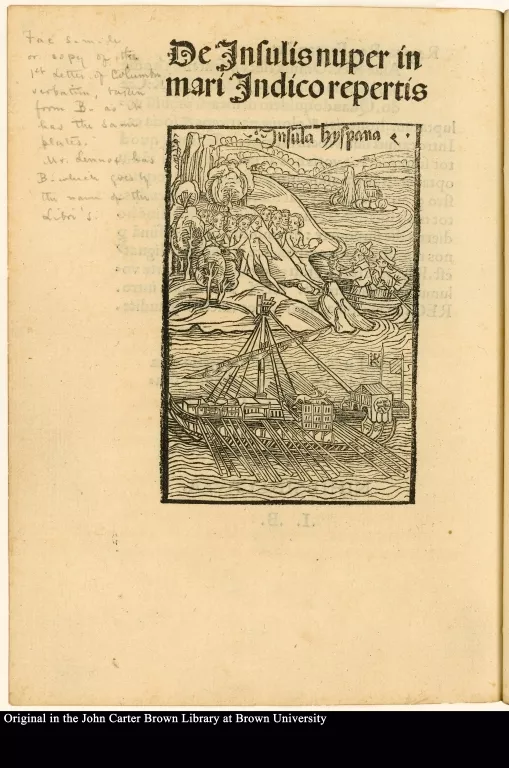

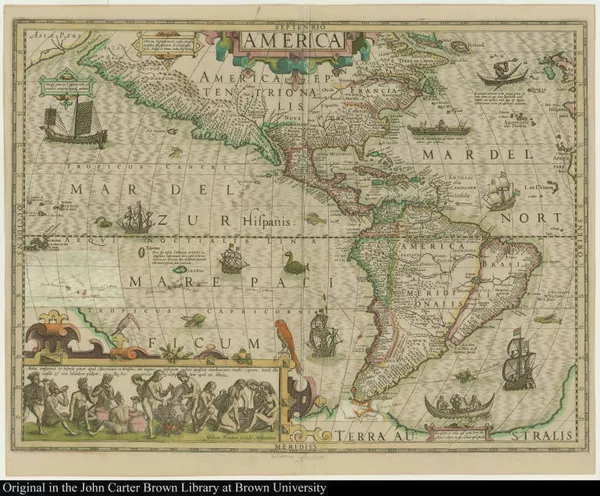

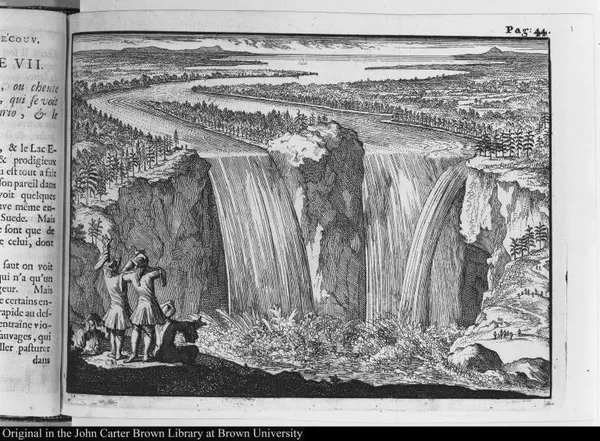

The idea that the Indians descended from the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel seems to have been discussed early in the sixteenth century, but was not proposed in print until 1567. Joannes Fredericus Lumnius's De Extremo Dei judicio et Indorum vocatione (Antwerp, 1587) was apparently the first book to set forth the thoughts associated with this concept. Several Spanish writers, some of whom worked in sixteenth-century Mexico, also circulated in manuscript form the idea of a Hebrew origin. Aztec legends of great migrations helped to inspire this view, but for the Spanish, it was just one of several competing theories.

The Hebrew origin theory gained new vitality in 1644, when a Portuguese Jew named Antonio Montesinos arrived in Amsterdam from South America. Montesinos spoke of a mysterious "Holy People" hidden in the mountains of the Spanish colonies. The people had disclosed themselves to Montesinos as Jews, he said, but had kept their religion hidden from the Spaniards, though they had long ago converted the natives in their midst to Judaism. It was their intention to come forth, rid themselves of the Spaniards, and reunite with Israel. Montesinos's account created a stir among the Amsterdam Jews and interested many gentiles.

The story was disseminated in print by Rabbi Manasseh ben Israel, who was also of Portuguese background. Manasseh was a brilliant scholar and writer and the book was but one of several successful publications. The work was published the same year in Latin (Spes Israelis) and in English (The Hope of Israel), and numerous other editions were printed. In addition to presenting the story of Montesinos, Esperanga de Israel also related Manasseh's own views on the subject, drawing comparisons between American Indian customs and Jewish tradition, and predicting a return to Jerusalem. In this complex relation, drawing on much existing thought, Manasseh even refers to the first Hebrew Americanum, Abraham Farissol's [Iggereth orhoth 'olam], (Venice, 1586).

The most famous of all books on the subject, Manasseh's work appeared at about the same time as several others, including Thomas Thorowgood's Jews in America, or Probabilities that the Americans are of that Race (London, 1650). Thorowgood's millennialist sentiment corresponded well to Manasseh's. Thorowgood wanted to hasten the final Christianization of the Jews, fulfilling the Biblical prophecies, while Manasseh saw full dispersal of the Jews as a necessary step leading to the coming of the Messiah. The worldly objective of both men was the readmission of the Jews to England, from which they had been banned since 1290. Despite efforts made in Parliament, however, the naturalization of Jews in Great Britain was still a century away.

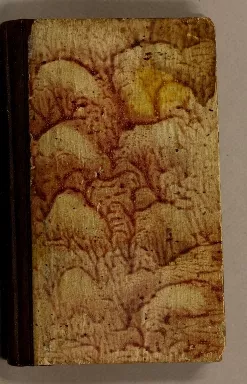

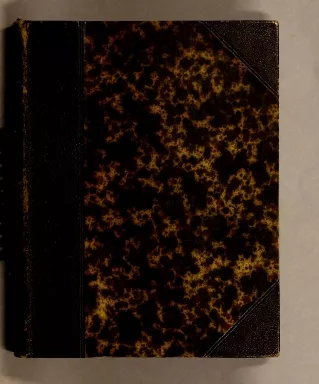

37

Robert Boyle

Some Considerations Touching the Usefulnesse of Experimental Natural Philosophy

Oxford: H. Hall, for R. Davis, 1664-71

American subjects often appear in the copious writings of Robert Boyle, the great English chemist and natural philosopher. He had various links to the English colonies, whether through his governorship of the Corporation for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England or his role on a council managing the colonies. He sometimes became directly involved, as when he provided John Eliot with financial assistance for an edition of the famous Indian-language Bible printed in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Boyle’s Some Considerations Touching . . . Natural Philosophy (originally published in Oxford in 1663), contains numerous references to American phenomena and natural resources, especially its food, drink, and medicines.

"For almost every day either discloses new Creatures, or makes new Discoveries of the usefulness of things; almost each of which hath yet a kind of Terra incognita, or undetected part in it. How many new Concretes, rich in Medicinal virtues, does the New World present the inquisitive Physicians of the Old?"

Maize, which grows where wheat will not, is just one of the many natural treasures that excite and amaze him. As shown in the exhibition, Boyle’s “Appendix,” page 34, discusses tobacco, indigo, and the wonderful way Indians use the cassava plant. In other writings, he explored still other facets of the natural world of America, from hurricanes and Andean winds to Indian mining techniques.

Another side of Boyle’s consciousness, informed by his religious convictions, emerges in his book, The Excellency of Theology, Compar’d with Natural Philosophy (London, 1674), a work later translated into Latin and German. There he discusses what he perceived as the relative uselessness to human civilization of the Spaniards’ monumental mining operations in America. Boyle rejected, on the whole, the pervasive materialism inherent in the advancement of commerce that was brought on by the new discoveries in geography. For Boyle, the true value of the New World lay not in its rich veins of mercury, gold, and silver, but in the new forms of life that excite the intellect and the new foods and medicines that would improve the lives of all humans.