1. Geography and History

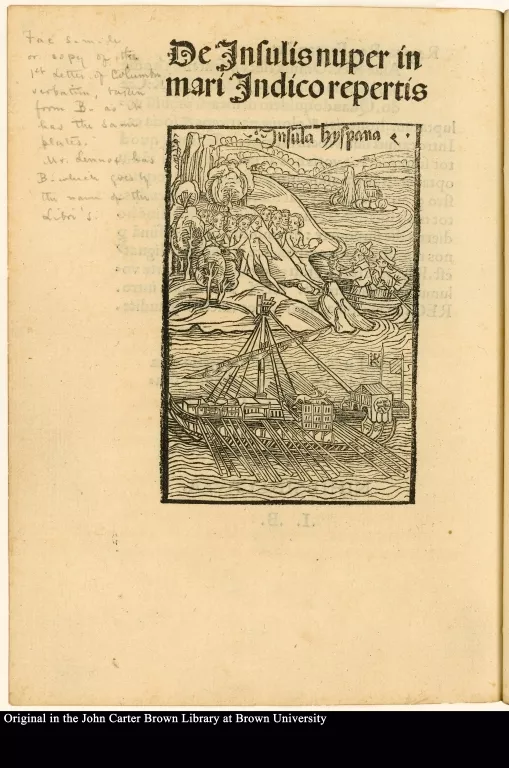

De Insulis nuper in mari Indico repertis

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1The earliest Americanum, or book about America, is the famous letter of Christopher Columbus to the court of Spain, reporting on his findings. Its contents anticipate much about how the Spaniards, the first colonizers, viewed the new lands and would continue to view them.

While describing the islands' physical features, Columbus's report focuses on three key points: first, that the islands are rich in gold and other natural resources; second, that these riches are now the property of Spain; and third, that the islands are populated by an attractive and tractable people who by his actions have become subjects of the king and queen. He also believed them to be imminent converts to the Holy Faith.

Columbus saw himself not as an emissary to these people but as the agent of their new ruler. The role of emissary was reserved for his meeting with the great Khan, the leader of a civilization comparable to Spain's, which he expected to find on the Asian mainland. As a technologically inferior culture, the islands were automatically deemed appropriate for conquest.

The explorer stressed that his arrival was an event of high importance and that his claim for Spain represented a victory granted by God to the king and queen. The riches, of which gold is most frequently mentioned, were intended to accrue to the rulers of Spain. In justification of his journey, Columbus promised all the gold their Majesties might require, as well as spices, cotton, mastic gum, drug aloes, and—finally—slaves.

The island natives, who, Columbus observed, were without clothing, were described as timid, guileless, and vulnerable, as well as intelligent, skillful, and pleasing in form. Columbus assumed a mantle of paternalism and generosity, making many gifts and forbidding the sailors to take advantage of the people. Since the islanders had no iron and lacked weapons comparable to the Europeans', he was confident that they represented no danger to the explorers. Aware of their belief that his company was from heaven, Columbus was also unconcerned about the dangers posed by their stories of fierce natives from another island, who were said to be warlike and to practice cannibalism.

Columbus's conception of his mission existed in two dimensions, earthly and spiritual, and was of overarching importance, he believed, in both. The worldly benefits were to come not only to Spain, he concluded, but to all Christians. At the same time, great fame was to be visited on the sovereigns through the religious conversion of untold nations in the new lands—a momentous spiritual event.

Thus began the greatest colonial undertaking of modern times, an empire to rival that of the Romans. Spain would exploit the resources of the New World as its assumed just right in the age-old role of conqueror. It would also export European culture, laying divine claim on a people who appeared to be without the practices of religion. It was a Holy Mission in two realms, and it was to be fulfilled as Columbus envisioned. There is in his letter not the slightest suspicion, however, that the new lands would also have a tremendous impact on the lands of his fathers.

Cosmographiae introductio

1507

-

p. 7

p. 7Columbus sought a shorter path to the "Indies" and assumed at first that he had reached Asia. "Cuba," for example, he took to be the local name for Japan. While the explorer took note of native names and reported them to his sovereigns, the name "Indies" became inextricably linked with what Columbus recognized by the time of his third voyage to be a rich new territory. He applied the term "Indias Occidentales," or West Indies, in his own writing.

The name "America" happens to resemble a variety of native names, such as Ameca, but we owe its application to the continent to a German geographer. In 1507, Martin Waldseemiiller published two world maps with the new lands identified as "America." Waldseemuller justified such usage in his pamphlet Cosmographiae introductio, which also contained Amerigo Vespucci's accounts of his New World voyages. The pamphlet enjoyed at least four more editions or issues the same year, and the map itself was printed in at least 1,000 copies. The success of Waldseemiiller's booklet propelled the name "America" into popular usage and resulted in the competing usage of "Americans" for the native inhabitants, who continued to be known as "Indians" in other publications.

Waldseemiiller used Vespucci's voyages as his source of geographical information on the New World and mistakenly identified him as the discoverer of the fourth part of the world, after Europe, Asia, and Africa. The name was specifically applied to South and Central America and the West Indian islands. Waldseemiiller drew the curious conclusion that it was proper to name the continent for this eminent male explorer because Europe and Asia took their names from women. The geographer erred even in this perhaps lighthearted suggestion, since the names for Europe and Asia probably derived from the Assyrian words for "West" and "East." The symbolic representation of the continents as women does, of course, enjoy a long tradition.

The success and wide-ranging influence of Waldseemiiller's early maps and writings overtook his own professional reconsideration. By the time he realized his error in assigning priority to Amerigo Vespucci and attempted to recall the use of the name America, it was too late. The name was already too deeply entrenched in common usage.

Vespucci's book of travels appeared in no fewer than thirty editions even before the end of the sixteenth century. It was printed everywhere from Rome to Antwerp and from Paris to Leipzig. While Amerigo Vespucci was not the bold innovator we know in Columbus, he did take part in as many as four transatlantic voyages between 1497 and 1503, and he provided a relatively lengthy and adventurous account of his company's encounters with natives, describing their appearance and customs. One of the earliest portrayals of New World cannibalism appears in his relation. In the story of his third voyage, he described females who killed and ate a young member of the crew while the other Spaniards watched in horror. Telling is Vespucci's account of the process of policy making on the first voyage: the Spaniards first determine to treat the natives as their friends; failing that opportunity, they will treat them as enemies, but in the end, they intend to capture as many as they can and make them their slaves.

Introductio in Ptholomei cosmographia[m]

1512

-

p. 14

p. 14While the earliest Polish Americanum is Joannes de Sacro Bosco's Introductorium of 1506, Jan ze Stobnicy's introduction to Ptolemy, the second most venerable work, is of greater visual interest because of the two maps apparently issued with it. These maps are clearly copies of the hemispheric representations that appeared at the top of Martin Waldseemiiller's large map of the world in 1507. One of the maps presents the known continents of Europe, Africa, and Asia. The other, the American map (see fig. 1.3), was based in part on the reports of explorations up to that time but also required a sizable leap of Waldseemiiller's imagination in terms of the placement and extent of the land mass. The essence of his achievement is the representation of two continents connected by a peninsula, with information on the Pacific coastline and northern reaches being necessarily limited and conjectural, but with manifest separation from Asia. Waldseemiiller's remarkable graphic proposal was not confirmed until the global circumnavigation completed by Magellan's crew.

For many years, the Jan ze Stobnicy version was the only known copy of the Waldseemiiller map, which was not rediscovered until 1901. It is to the Polish author's credit that Waldseemtiller's work was thus disseminated, though it is unfortunate that he failed to credit the German cosmographer. These maps are probably the earliest of any to be printed on Polish soil, and the captions, less than ideally legible, differ in several ways from the Waldseemiiller original. The name "America" does not appear.

Jan ze Stobnicy (Joannes Stobnicensis), born at Stopnica, Poland, around 1470, was a professor of philosophy at the University of Cracow, one of the great centers of learning in Europe; he later joined the Franciscan order. His geographical text, really a compilation from several authors, is also distinguished by being the first Polish book to contain several firm references to the New World, as opposed to the slight reference to an unspecified new world in Sacro Bosco. Jan ze Stobnicy's American remarks, like his maps, are demonstrably derived at least in part from Waldseemtiller's text, and he credits Vespucci three times as the continent's discoverer, making no mention of Columbus. The fourth part of the world, while named "America" for the explorer, is said to be known popularly as "novus mundus."

Claudii Ptolemaei Alexandrini Geographicae enarrationis libri octo

1535

-

p. 1

p. 1The power of the ancient Romans was so great, and their travels so wide-ranging, that they necessarily acquired a vast and sophisticated knowledge of geography. Such information was in fact systematically collected. Roman knowledge passed to the Arabs, who preserved and developed it, and it was only with the Renaissance that this ancient knowledge was recovered by Europeans. The discovery of the New World and the growing recognition of its importance in no way diminished the discipline of ancient geography, which remained a subject of active scholarship, as new or modern geography became a field in its own right.

The last great astronomer of ancient times, Ptolemy, was a Greco-Egyptian mathematician and geographer in the second century a.d. He is most famous for working out the earth-centered cosmography that was commonly accepted until the heliocentric Copernican system began to displace it in the sixteenth century. Ptolemy knew perfectly well that the earth was round and prepared estimates, admittedly small, of its size. His treatise on geography is almost as important as his work on astronomy, although it is less well known. The first printed edition of Ptolemy's geography appeared in 1475, and from 1508, editions began to be published with some treatment of the new discoveries in the West. The edition of 1535 is of special interest to Americanists because of the editorial comments of Michel de Villeneuve, i.e., Michael Servetus, a Spanish physician and scholar who worked and traveled across Europe. As an example, on the back of map 28, "Oceani Occidentalis seu Terrae Novae Tabula," Servetus makes an effort to correct existing misapprehensions:

Therefore, those who strive to name this continent "America" are very much mistaken, since Amerigo [Vespucci] went to the same land long after Columbus; nor did he go there with the Spanish, but with the Portuguese, in order to exchange his wares.

Michael Servetus is best known in the history of medicine and science for his landmark discovery of the circulation of the blood through the lungs, announced in book five of his Christianismi restitutio (1553). The impact of this discovery was diminished severely by the early destruction of all but three copies of that publication. To his ultimate misfortune, Servetus also applied himself diligently from his youth to the study of the Scriptures, using the recently printed polyglot texts that widened the availability of the Bible to scholars. Servetus went in search of what he felt to be a simpler basis of theology, distancing himself from the Trinitarian constructs of church doctrine. The Unitarian views resulting were published in De trinitatis erroribus libri septem (1531) and Dialogorum de trinitate libri duo (1532), which aroused the enmity of Catholic and Protestant authorities alike. The books, printed when Servetus was barely twenty years old, were banned and burned, and the author condemned.

The young student assumed the name Michel de Villeneuve (as listed in the Ptolemy), found work as an editor of Classical texts, and pursued a medical career. Despite his success in taking on a new identity and working as a physician for two decades, Servetus eventually felt impelled to seek further publication of his theological views. As a result, he was captured while traveling through the theocracy of Geneva. After having been tried for heresy by Jean Calvin, the founder of the Reformed Church, he was burned at the stake in 1553.

In the trial, Servetus seems to have been one of the first to have identified America as a refuge from the persecutions characteristic of Europe in the Reformation. Calvin's record of the event reports that Servetus charged he would denounce him to the new lands, where he would establish opposition to Calvin's tyranny.

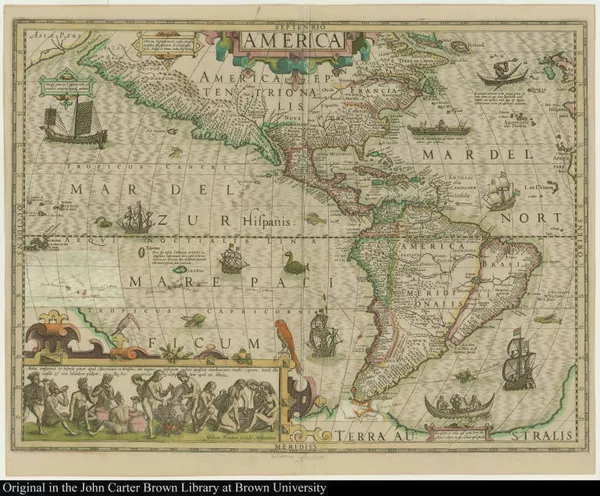

America

1619

-

p. 1

p. 1With general acceptance of the term "America" for the continent of South America, it was Gerardus Mercator who applied it to the north and introduced in printed form the distinction of North and South America, "Americae pars septentrionalis" and "Americae pars meridionalis." These first appeared in his Latin world map of 1538, which had its basis in Ptolemy. The Mercator names eventually achieved nearly universal acceptance, although some non-standard usage persisted well into the eighteenth century. Some German writers, for example, called most of North America "Kanada," reserving the name "America" for the lands to the south.

Gerardus Mercator began a great atlas in 1585 which was completed by his son Rumoldus ten years later. The Atlas sive Cosmographicae meditationes (first published, Dusseldorf, 1595) is the first complete version of the three-part work. (For a detail of the 1623 edition, see fig. 1.4.) Mercator atlases were extensively published, modified, and augmented in Latin, German, English, French, and Dutch. The Atlas minor, das ist: Eine kurtze jedoch gründliche Beschreibung der gantzen Welt (Amsterdam, 1651) was a more modest atlas, aimed at a wider market, and was an enormous success.

Mercator's greatest impact, however, was the new projection of the world presented in many of his maps after 1568. For navigators' maps of the world, the Mercator projection has been used more widely than any other projection. It has the advantage of showing true direction and presents latitude and longitude as straight lines that intersect at right angles. On the other hand, this cylindrical method increasingly misrepresents areas and distances as one moves away from the equator.

Wunderbarliche, doch warhafftige Erklärung, von der Gelegenheit vnd Sit...

1590

-

p. 9

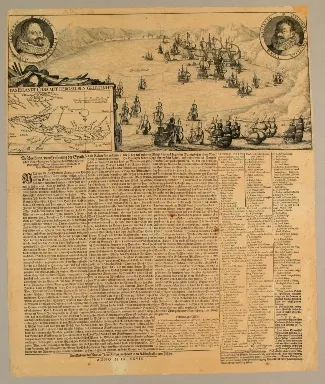

p. 9"Virginia," the first English colony in America, was a project promoted by Sir Walter Raleigh, an adventurer seeking to elevate his position in the court. Among those chosen to accompany the colonization attempt in 1585 were his Oxford tutor, Thomas Hariot, and a gifted artist, John White. Hariot, who later established a reputation as a mathematician, had the assignment of studying the customs of the native population and describing the new land's geographical features. White, who served as governor of a later settlement, was to draw and paint what he saw and act as a surveyor.

Raleigh had much to gain from the success of the colony and saw to the publication of Hariot's report as A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia in 1588. On a visit to London, the Frankfurt engraver Theodor de Bry was encouraged, possibly with the aid of Richard Hakluyt, to publish the report together with engraved versions of the watercolors of John White. The magnificent publication that resulted was printed and engraved the same year in four languages: Latin, German, French, and English. It also formed the first volume of de Bry's great series of lavishly illustrated travel accounts, known collectively as his America series or the "Grands Voyages."

Hariot's report, while generally accurate, also served the purposes of propaganda, painting the colony in the most positive light. The illustrations of John White are characterized not only by evident artistic skill but by a high level of accuracy. His portrayal of Indians and nature would establish a standard of presentation, and the images themselves would be copied countless times in the centuries ahead (see fig. 1.1). The work of both men is prized as a careful representation of local conditions at the time of the settlement. Occasionally, the de Bry engravings differ slightly from White's watercolors, bestowing a more Europeanized appearance on the Indians. Contemporary copies of White's originals have largely been preserved and are kept in the British Museum; they have recently been published.

The area actually treated by White and Hariot is Roanoke Island and the coast of what is now North Carolina. The report emphasizes natural resources and products, such as metals, furs, dyes, nuts, turkeys, herring, and local food crops; also provided is an account of the indigenous population and their way of life, accompanied by observations and anecdotes. Even as a man of science, Hariot cannot fully account for the unintended impact of this European incursion. As it is expressed in the English edition, "within a few dayes after our departure from every such towne, the people began to die very fast, and many in short space... This happened in no place that wee coulde learne but where wee had bene." The unavoidable introduction of alien disease to those without immunity (in this case perhaps smallpox), so pernicious to New World populations, could not yet be recognized. Nevertheless, Hariot closes his account with his positive hopes for the new colony, "seing therefore the ayre there is so temperate and holsome, the soyle so fertile." He assumed that an amicable coexistence with the Indians would be possible.

Beschryvinghe vander Samoyeden Landt in Tartarien

1612

-

p. 9

p. 9The first work in this small compendium edited by the Dutch cartographer-bookseller Gerritsz is Isaac Massa's description of Russia, which gives the volume its title. Massa, born at Haarlem in 1587, and hence a countryman of Gerritsz's, was sent to Moscow in his teens to learn about commerce, especially the silk trade. He remained in Russia for eight years, during which time he also learned much of Russian geography and history and compiled reports from explorers.

Massa's account of Russia and Tartary focuses on the people and natural phenomena, but he closes it with the opinion that the inhabitants of America arrived there by crossing the "Anian Strait" between Asia and America. This idea had already been proposed by Jose de Acosta in 1588, but it is all the more significant when voiced by a visitor to Russia who had contact with explorers at a time when little was known about Siberia. Massa reported estimates of the Anian Strait's breadth to be as great as 100 miles, though he thought it more narrow. What we recognize today as the Bering Strait has a width of only 56 miles.

The two hemispheres shown in Gerritsz's world map (fig. 1.5) feature the various discoveries mentioned in the volume and display both the further reaches of Asia and the assumed extent of North America. On the overleaf to the map of Siberia, Gerritsz elaborates on the question of migration, mentioning Massa's proposal and New France. In his preface, he discusses Henry Hudson's search for a Northwest Passage, as well as Martin Frobisher, Newfoundland, Virginia, Peru, and the writings of Acosta. The last item in the volume is Pedro Fernandes de Queiros's Verhael van... Australia incognita, translated from his 1610 Pamplona memorial requesting permission to establish a new colony in the Pacific.

Later the same year, Gerritsz issued a new edition with a supplement containing the first printed accounts of Hudson's North American discoveries, as well as the earliest separate map of Hudson Bay and the adjacent country, detailing the area shown on the world map in this first edition. The full work soon appeared in Latin and was reprinted in 1613, finding its way also into the de Bry family's East Indian series in German and Latin.

The royal commentaries of Peru, in two parts

1688

-

p. 9

p. 9Anchored in two worlds throughout his life, Garcilaso de la Vega was born at Cuzco, Peru, in 1539, the son of a Spanish conqueror and an Inca princess. His cultural dichotomy and the relationships from which it stemmed informed his life's work. As a child, he was steeped in the oral tradition of the Inca, whose history he was encouraged to chronicle. Yet at the age of twenty, he was called to Spain and lived out his adult life there, never to return to South America.

His first work, La Florida del Inca, written about 1584, was first published in Lisbon in 1605. This study of Hernando de Soto, while a work of non-fiction, had something of the narrative quality of a novel, with its battle scenes and dialogues. The author viewed de Soto's mistaken journeys as a tragedy reflecting both man's greatness and the ultimate futility of many of his endeavors. Significantly, the book was not published in Spain until the eighteenth century, but was already translated into French by the mid-seventeenth century.

Garcilaso's second important work, the culmination of his life's efforts, was the Commentarios reales, que tratan del origen de los Yncas, reyes que fueron del Peru, first published, Lisbon, 1609 (part 1) and completed, Cordoba, 1616, just before the author's death. While indisputably a historical narrative, the literary properties of this book qualify it as the first great work of Spanish American literature.

The first part, a treasury of native American heritage, relates the story of the Inca before the arrival of Europeans. It gives an account, as retained from stories learned by Garcilaso as a child and youth, of Inca history, government, religion, and custom. The second part relates the Spanish conquest of the Inca, including criticism that would be unavoidable in any history other than a whitewash.

While recognized today as a responsible work of history, it incurred the wrath of contemporary Spaniards, who pointed to the author as an Indian and defamer of Spain. Yet Garcilaso had no such intention, truthfully recounting historical fact and even judging the Spanish conquest as a worthy and important development for his people, in its bestowal of Christianity. In this regard, he differed from Bartolome de las Casas, who discredited the whole colonial undertaking. Nevertheless, the Spanish court eventually forbade the sale of Garcilaso's book as a rebellious and anti-Spanish document.

An abridgment appeared in English as early as 1625, and the first part was translated into French by 1633. In 1688, the full work appeared in English. While an imperfect translation of Garcilaso's original, this English edition is of greater visual interest than the first Spanish edition, which is not illustrated. Chapter eleven of the second part, relating the arrival of Pizarro in Peru, tells of the fear of the Indians upon seeing a tall European in armor, Pedro de Candía. The complex entanglement of the author with the narrative is conveyed by Garcilaso's note that he went to school with the son of this Pedro de Candía. One is touched by his caution in citing a Spanish source for another anecdote, a story from Pedro de Cieza de León, "that so I might have the Testimony of a Spanish Author, in confirmation of the truth of what I have wrote."

The sea-atlas or the watter-world

1660

-

p. 1

p. 1One of the essential tools of the navigator was the nautical chart that accurately portrayed the seacoasts. In the seventeenth century, it was the Dutch who, as masters of the seas, pioneered in the production of quality land and sea maps and atlases. Working chiefly in Amsterdam, they printed in Dutch, French, Latin, English, German, and Spanish, fairly dominating the European trade for a century.

Hendrick Doncker was one of the most prolific publishers of maritime works in the latter part of the seventeenth century. His success is evident in the wide distribution of his sea atlases and navigation books, which were distinguished by being the most up-to-date of any available in his time. Doncker's Zee-atlas, first published in 1659, was an important, original creation that went through editions with prefatory text and title pages in English (The Sea-Atlas, 1660), French (L'Atlas de Mer, 1689), and Spanish (La Atlas del Mundo, [1669]), as well many Dutch editions. His later Nieuwe Groote Vermeerderde Zee Atlas, 1669, was a still larger work in format and volume, and its publication was continued and further improved by Doncker's son, also named Hendrick.

The elder Doncker's Sea-Atlas, as here represented, merely masquerades as an English edition; it is a collection of navigational charts with place names in Dutch and is fitted out with the standard Dutch preface-only the title page is in English. Yet at least one 1660 copy survives with text in English, proving the existence of that edition.

The preface describes such colonies as Brazil, Cuba, Florida, and Peru, and provides a short history of world navigation, including the American discoveries. The ten American maps in this copy show coastlines stretching from Greenland and New France in the north to the Strait of Magellan, as well as the islands of the Caribbean.

"Profedens," appearing on the map of New Netherland, Virginia, and New England, is thought to be the first appearance of Providence, Rhode Island, on a printed map. The listing of such neighboring places as "Warrick," "Klips kil" (Fall River), "Pleymuyt," and "Baston" indicates the settlements of importance. New Netherland as here laid out is shown in the twilight of its existence; in 1664 it would yield to British control. The Dutch settlements eventually became part of the states of New York, Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, and Pennsylvania.

Nouvelle decouverte d'un tres grand pays situé dans l'Amérique, entre ...

1697

-

p. 1

p. 1Hennepin's Description de la Louisiana (Paris, 1683) was the first printed account of Louisiana, as well as the earliest description of Niagara Falls. The work is amplified in his Nouvelle decouverte, which also provides the first engraved view of the falls. In the London edition of 1698, A new discovery of a vast country in America, he writes,

"Betwixt the Lake Ontario and Erie, there is a vast and prodigious cadence of Water which falls down after a surprizing and astonishing manner, insomuch that the Universe does not afford its Parallel.

. . . The Waters which fall from this horrible Precipice, do foam and boyl after the most hideous manner imaginable, making an outrageous Noise, more terrible than that of Thunder. . . . From the great Fall. . . the two Brinks of it are so prodigious high, that it would make one tremble to look steadily upon the Water, rolling along with a rapidity not to be imagin’d."

The author discounts comparisons with Switzerland and Sweden as inadequate to describe the Niagara.

Hennepin was a Franciscan Recollect friar who took part in the expedition that discovered the upper Mississippi. He was captured by the Sioux but rescued a few months later, and returned to France, where he began to publish. The magnificent achievement of his narratives is shrouded in controversy as a result of his extravagant claims that he was the expedition's leader and that he traveled on to the mouth of the Mississippi. Despite an earnest desire to return to North America, he failed to gain royal approval. The narratives remain a rich source for descriptions of Indian life and of nature, even if Hennepin's assertions cannot always be accepted.

2. Missions and Religious History

Copia dela bula dela concession q[ue] hizo el papa Alexandre sexto al Re...

1511

-

p. 1

p. 1In the era of the discoveries, the Catholic Church in Rome was not only the seat of responsibility for foreign missions, but was still the only supranational authority available for the arbitration of conflicting interests. By the closing years of the fifteenth century, the papacy was approaching the peak of its outward splendor, even if its claim to universal political sovereignty had been broken with the death of Pope Boniface VIII, nearly two centuries before. Alexander VI, pope from 1492 to 1503, was a Spaniard whose illegitimate children included Cesare and Lucrezia Borgia. The personal power and corruption associated with his reign made his name symbolic of worldly impiety.

In 1493, Alexander VI established the legality of Spain's New World claims by setting a line of demarcation in the Atlantic Ocean, assigning lands and waters east of the line to Portugal, and those west to Spain. Being just one hundred leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands, it effectively granted all of America to Spain, while according India and Africa to Portugal. The following year, the countries themselves confirmed the pope's ruling through the Treaty of Tordesillas, but moved the line 270 leagues further west, in the interest of Portugal's African and maritime pursuits. The new line, running through the eastern projection of South America, established the legal basis for the future Portuguese colony of Brazil. At the time of the treaty, geographical knowledge was still very limited, and it continues to be debated whether Portugal was secretly aware that the movement of the line to the west would give it control over a large portion of South America.

The 1493 Bull was of sufficient importance for Spain to be printed twice around 1511, but neither Spain nor Portugal chose to make the land grants to the papacy that a bishop had proposed in 1493 as a reward for the pope's role in arbitration. Lacking the resources for the large campaigns needed for the conversion of the natives, the Church turned the financing and administration of missionary activities over to the Spanish crown.

Histoire de la mission des peres Capucins en l'isle de Maragnan et terre...

1614

-

p. 5

p. 5Claude d'Abbeville's history of the French Capuchin mission to Maranhao seems to be the earliest account of that island off the coast of Brazil. It is also an expression of the competitive spirit between the Capuchins and their rival missionaries, the Jesuits, with whom they also contended in Canada. The Capuchin author only remained for about four months in the colony, returning to Paris with six Indians whose presence in the city caused a sensation. He sought to promote the colony, emphasizing the positive, as exemplified in the portrayal of the ideal of peaceful conversion of the naked masses. The accompanying illustration (fig. 11.1) shows Spaniards and Indians, soldiers and priests kneeling together, all equal before the symbol of the Church.

The French colony was a political liability, however, being conducted on land already claimed by Portugal. The mission was cut short after the marriage of Louis XIII in 1615 to a Spanish princess, in an effort to maintain good relations with Spain, which was then in political union with Portugal. Claude d'Abbeville's descriptions of nature and the Indians of Maranhão remain as the intellectual legacy of that short-lived mission.

Question moral si el chocolate quebranta el ayuno eclesiastico

1636

-

p. 7

p. 7The author of numerous legal and historical papers, Leon Pinelo was born in Peru and served Spain's Consejo de las Indias as an advocate. In Question moral, he pondered the ethical problem of priestly consumption of chocolate as a drink before mass. He concluded that it does not break the fast, but discoursed at length on chocolate, its origin, and methods of preparation. His work stimulated a controversy that continued into the eighteenth century. Along the way, he also considered the issue of priestly smoking. Citing various ecclesiastical regulations, Leon Pinelo concluded that priests would sin grievously by smoking tobacco prior to the celebration of mass.

In this same volume, the author described nearly every beverage known at the time (i 18 in all), particularly those of America. The drinks include cassava beverage, a drink made from the coca plant, and pulque, which is made from the aloe plant. The author took a negative view of the excessive consumption of some beverages by Indians.

A key into the language of America: or, An help to the language of the n...

1643

-

p. 3

p. 3The exacting spiritual standards Roger Williams employed and his particular interpretation of Christianity's mission led to repeated conflicts with his fellow churchmen in New England. He took issue with the various ways civil authorities in Massachusetts impinged on freedom of conscience, with the eventual result of his banishment in 1635. Traveling southward in 1636, Williams turned his energies toward the creation of a new colony where differing religious views could flourish in a spirit of toleration. His leadership in Providence and nearby settlements also led to the development of government forms that were, in general, more responsive to the consent of the governed than those in Massachusetts had been.

Roger Williams was among the first ministers in New England to take a serious interest in the conversion of the Indians. The months he spent living among them and learning about their life gave birth to his book, A Key into the Language of America. At the time, Williams was nearly unique among English colonists in his interest in native culture and religion, treating his Indian neighbors as equals. He was also the first New Englander to consider their legal rights, arguing against the legitimacy of royal land grants in Massachusetts and purchasing land directly from Indians when he founded the colony of Rhode Island. He continued to work for fair and egalitarian treatment of the Indians, with the result that he was able to forge successful alliances that benefited all of New England until the time of King Philip's War.

Williams's linguistic treatise touched on every aspect of Indian life, providing Narragansett vocabulary and anecdotes to assist the reader's understanding. The topics of chapters included salutations, eating and entertainment, sleep and lodging, names for numbers and family relationships, household business, parts of the body, basic communications, telling time, and the seasons. Further chapters dealt with travel, the heavens, weather, animal and plant life, fish and the sea, nakedness and clothing, religion, government, money, trading, hunting, games, war, art, illness, and death.

Everywhere there is evidence of his egalitarian spirit. In naming the parts of the body, Williams observed, "Nature knows no difference between Europe and Americans in blood, birth, bodies &c. God having of one blood made all mankind, Acts 17." In his chapter on religion (see fig. 11.4), he was careful to include Indian religious terms and concepts along with those he used to explain Christian doctrines. He reported a discussion with a Connecticut Indian in which the source of religious authority was at issue. The Indians accepted their ancestors' oral tradition that souls go to the southwest, but no one could tell of the destiny of souls by experience. An Indian noted, however, that the Englishman brought "books and writings, and one which God himself made, concerning men's souls, and therefore may well know more than we that have none, but take all upon trust from our forefathers."

Already in New England, Williams had doubts about the legitimacy of conversion; as his religious thinking continued to develop, he began to question whether Indian religious practices should be displaced by those of the Europeans, a sentiment that ended his work in missions.

Rosa de S. Maria virgo Limensis è Tertio Ordine SS. P. Dominici

1668

-

p. 7

p. 7The very first American to be declared a saint by the Roman Catholic Church was Rosa of Lima in 1671, nearly two hundred years after Columbus first carried Christian beliefs to the New World. Born in 1586 to parents of Spanish extraction, she appears to have been an unusually devout child. Having taken a vow of virginity fairly early in life, as well as showing many other signs of disowning a worldly existence, she became a Dominican nun at the age of twenty. Especially in adult life, she turned to self-denial and mortification, habitually wearing a spiked metal crown and a girdle of iron chains, and lying upon a bed of thorns, glass, stones, and potsherds. The hallucinations associated with severe fasting understandably took, for her, the form of religious imagery.

Following her death in early adulthood in 1617, various miracles are said to have taken place. She was beatified in 1667, just fifty years later. The standard biography of the Peruvian saint, Leonhard Hansen's Vita mirabilis . . . sororis Rosae de S. Maria, was first published in Rome in 1664, quickly becoming a bestseller across Europe. It was printed in Spanish in 1665, in Polish in 1666, in German in 1667, in Flemish in 1668, and in Portuguese in 1669. Multiple editions appeared in each language as Rosa's fame spread among the faithful.

Even before the success of Hansen's volume could be predicted, those who wished to promote Rosa's cause sought the widest possible circulation for her life story. Antonio Gonzalez de Acuna, advocate for her beatification in the Vatican, arranged for the preparation of a concise biography, based upon Hansen, that could be sold more cheaply than the latter book. A young theological student in the Roman College, Giovanni Lorenzo Lucchesini, agreed to take on the task.

The resulting volume, the product of Lucchesini's literary skill, had success comparable to the work on which it was based. The Compendium admirabilis vitae Rosae de S. Maria Limanae (Rome, 1665) was reprinted in Latin under various titles, carrying with it the name of Gonzalez de Acuna, who had seen to its approval and publication. The edition exhibited also included documents regarding her beatification. French and German translations were printed in 1668, and a Spanish edition appeared at Rome in 1671. Several French editions were even followed by an abridged French version. The work was routinely associated with the Dominican Gonzalez de Acuna's name until 1696 when the name of Lucchesini at last appeared on the title page of the ninth Latin edition, printed at Rome. Despite accusations of plagiarism, the literary responsibility of Lucchesini, a Jesuit, was ultimately vindicated. Understandably, various editions continue to be cataloged under Gonzalez de Acuna's name even today.

Antinomians and Familists condemned by the synod of elders in New-England

1644

-

p. 1

p. 1Writers on religion in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, while generally impatient with heresies of whatever kind, seemed to have a special reserve of ire to vent on those religious traditions, like that of the Quakers, that permitted women to contribute to religious thought. Such an element was certainly involved in the persecution of Anne Hutchinson, who became part of the Antinomian controversy. The name "Antinomian" was applied to those who were perceived as placing themselves above the moral law of the Old Testament. John Winthrop, governor of the Massachusetts colony, describes her in this way: "Mistris Hutchison ... a woman of a haughty and fierce carriage, of a nimble wit and active spirit, and a very voluble tongue, more bold than a man, though in understanding and judgement, inferior to many women." Winthrop grants her wholesome scriptural teaching, but contends that she "dissembled" in order to join the church of Boston and charges that in private religious meetings, she quickly began "to set forth her own stuffe." Moreover, as a midwife, she was in a position to have considerable influence in the community.

Winthrop lays out the exchanges with Hutchinson in court, where she was charged. Her reasoned replies to her interrogators are rich with scriptural references and sensible observations. The authorities' reply, however, is: "you shew not in all this, by what authority you take upon you to be such a publick instructer." Her chief doctrinal crime seems to have been her belief in a "covenant of grace" in which the individual may experience direct intuition of divine grace and love, as opposed to the accepted doctrine of the "covenant of works." Hutchinson's offense, however, may be attributed in equal measure to her having overstepped the bounds of her feminine station. She defended herself by arguing that she was trying to follow the Apostles, a role traditionally associated with males. The assembled gentlemen appeared genuinely to fear that the gospel would be driven out of New England, and the result was a sentence of banishment. Hutchinson was identified with the worst Anabaptist excesses of Europe, with Satan threatening the Kingdom of Christ.

Anne Hutchinson and her family first moved with some supporters to a new colony on Aquidneck Island, present-day Newport, Rhode Island. Following the death of her husband, the family moved to New Netherland, a colony known for its relative tolerance. There, all but one member of her household were murdered by Indians in 1643.

Anabaptisticum et enthusiasticum Pantheon und geistliches Rüst-Hauss wi...

1702

-

p. 1

p. 1To state-church conservatives, the left-wing radical reformers were anathema. In particular, the Anabaptists or Mennonites, largely peasants with simple Christian enthusiasm, were marked by association of name with the most radical of their number, the revolutionaries who established a commune at Munster in Westphalia. Far from the modest, conservatively-styled agricultural Mennonites of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Anabaptists at Munster sought in 1535 to "reform" the very foundations of society, forbidding private property and traditional marriage. When Catholic forces with much slaughter retook the city, in their extreme reaction, they forbade any form of Protestantism.

More than a century later, the Society of Friends—the Quakers—were also to become the subject of much fear and loathing. While emphasizing inward spiritual experience in reaction to the formalism of Christianity in seventeenth-century England, the Quakers had some adherents who, in their enthusiasm, turned to shrieking and trembling with religious ecstasy. Others exhibited various forms of unusual behavior, appearing nude at public meetings, prophesying, or wearing sackcloth. The Anabaptisticum et Enthusiasticum Pantheon, a complex collection of German tracts featured here, highlights strange stories of Quakers committing murder and defiling religious articles. The work sought to expose all such excessive behavior, presenting stories and portraits of those who were felt to be the chief theological malefactors, like James Naylor, a Quaker with messianic tendencies; Jacob Arminius, who sought to soften the harsh determinism of Calvinism; and Menno Simons, a leader of the Dutch Anabaptists. Other illustrations emphasize violence and bizarre behavior. In fact, every departure from Orthodoxy, from the arch-heresy of Socinianism to New England Congregationalism, is held up to ridicule. In one illustration (pp. 168-169), representatives of suspect groups are shown, and the sectional head announces chapters on Quakers, Ranters, Robinsonians, Jews in England, and the conversion of the Indians.

In actuality, the editors fall short of presenting the horrors on every page that seem to be promised by the sensationalistic title pages; this is especially true of American subjects. A section on the conversion of the inhabitants, "Wie sie mit den Indianer verfahren," is a fairly straightforward, selective synopsis of early Puritan missions, citing essential English publications; a footnote on the savagery of Indians is the only part to suggest misdeeds of any kind. A separate publication on Oliver Cromwell and Hugh Peters, Der verschmitzte Welt-Mann und scheinheilige Tyranne, also issued in the collection, enumerates the beliefs of "Independents" or Congregationalists and lists, in a suitably negative tone, the ways the New England branch purportedly differs from the English. "The Law is no rule or guideline for life," and "It is indecent if one wishes to force a Christian to do good works," are among the tenets attributed to their religious code.

Magnalia Christi Americana: or, the ecclesiastical history of New-England

1702

-

p. 1

p. 1Even as successful experiments in religious toleration were being conducted in Rhode Island and Pennsylvania, another voice in Massachusetts pointed back with nostalgia to a simpler past when only right thinking was rewarded, and those who strayed from the prescribed path found banishment and death. Cotton Mather, the brilliant son of a family prominent in Boston church history, prepared a theological retrospective that outlined the Puritan struggle in the first eight decades on American soil. Opening with a line paraphrasing Virgil, Magnalia Christi Americana was intended to be a great epic history of New England. Through a collection of biographies, chiefly of ministers and governors, it painted such a rich portrait of early colonial life that it served as a source for numerous American authors, including Hawthorne and Melville.

Emphasizing the lives of exemplary men such as John Eliot, John Winthrop, and William Bradford, Mather's biographies presented moral lessons and engaging anecdotes; he delivered poignant accounts like the Indian captivity of the bravely resolute Hannah Swarton and admirable stories of model "praying Indians." The narrative also contains sermonizing and attacks against what Mather regarded as a decline in religious values. The idea that one might achieve salvation in any sect, as long as one conducted life diligently and conscientiously under its teachings, seemed to him a principle "fitter for Mahometans than Christians".

The latter part of Mather's history concerns those he felt to be the enemies of the New England Congregational establishment, figures like Roger Williams, Anne Hutchinson, and the defendants in the Salem witchcraft trials. Though he was a man of science known to intellectuals in Europe, and an early proponent of inoculation against smallpox, Mather accepted the existence of witchcraft as a reality and related in detail the accusations against the supposed witches. The thoughtful author of 450 printed and manuscript works nonetheless cast a critical eye on some of the proceedings, conceding that mistakes had been made in the Salem trials.

An account of the Society for Propagating the Gospel in Foreign Parts, e...

1706

-

p. 1

p. 1The English were the first Protestants to mount organized missionary campaigns. Under Cromwell, an ordinance was passed in 1649 establishing the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England. The charter of this organization was strengthened when the monarchy returned to the throne. Soon the Society of Friends, or Quakers, began their own efforts. In 1701, Dr. Thomas Bray, having visited Maryland under the official auspices of the Church of England, secured a patent for the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. The Anglican Church thus launched a campaign not merely directed at the souls of the Indians, but in competition with the Catholic Church, especially with their renowned front line troops, the Jesuits.

The Society's plans and reports were routinely publicized in printed sermons and other papers. One of the earliest such sermons contains the discussion of a report from Robert Livingston, Secretary for Indian Affairs in New York. Livingston maintained that the Indians of New York were in urgent need of ministers to instruct them in Christianity. The "French Jesuits," he noted,

were by all Arts and Terrors endeavouring to make Proselytes of them and had drawn over a considerable Number of them to Canada . . . where they had Priests to instruct them, Land to plant, and Soldiers to protect them in Time of War.

Livingston urged the "redeeming of the poor Indians from this Slavery to the Popish Priests" and the establishment of programs to instruct them in the "plain and true Principles of Christianity" (as opposed to the Roman doctrines). He then set forth how this was to be done. Missionaries, he said, should go and live among the Indians, learning their language, and erect a chapel and house. "And that each Minister should be furnisht with some cheap Toys, to give to the Indians, and so engage their Affections, as was the Custom of the French Jesuits among them &c."

The concerns expressed in the report are not only focused on spiritual welfare but touch on other abuses threatening the Indians' survival. As related by another correspondent in the same report (Mr. Moor),

The Indians are daily wasting away, and in forty years it seems probable that there will be scarce an Indian to be seen in all the English Parts of America. In the mean Time the Christians selling the Indians so much Rum is a sufficient Bar, if there were no other, against their embracing Christianity.

The reports discuss numerous problems faced by the missionaries, such as the difficulty in convincing Indians that Englishmen wish them a place in heaven when they steadily deprive them of space on earth.

Neuer Welt-Bot

1733

-

p. 8

p. 8The particularly strong missionary commitment of the Jesuit order and the political dimension that was commonly one of its facets are both displayed in this book as these traits came to be employed among the Chiquito Indians of Paraguay. Originally composed in Italian, the work was first published in Spanish as the Relacion historial de las misiones de los Indios, que llaman Chiquitos (Madrid, 1726). The first German edition appeared in 1729 under the title Erbauliche Geschichten derer Chiquitos. Italian and Latin editions were printed a few years later.

While chiefly an account of new missions to the Chiquito Indians, including descriptions of the population and environment, the work also contains stories of journeys and missions to various other Indian groups, the discovery of the Rio Paraguay, and the incursions of interlopers from Sao Paulo on the Paraguayan missions. The German editions added a description of Guiana and Cristobal de Acuna's account of the Amazon River, originally published in French in 1682.

The Jesuits in Paraguay oversaw the most famous of the "reductions," communal settlements of Indians begun in the seventeenth-century colonies to facilitate the teaching of Catholicism and Spanish ways and to make the most effective use of native labor. The missions prospered, and the Jesuit caretakers tried to protect the Indians against outsiders who robbed or kidnapped them for slavery.

Martin Dobrizhoffer, an Austrian Jesuit missionary who later came to Paraguay and prepared his own ethnographic study, wrote that some of the Indian accounts related by Vandiera strained his credulity. The work nevertheless provides a fascinating record of missionary efforts and perceptions.

Pennsylvanische Nachrichten von dem Reiche Christi, Anno 1742

1742

-

p. 3

p. 3Born at Dresden in 1700, Zinzendorf was raised in the atmosphere of German Pietism. The movement emphasized study of the scriptures and personal religious experience, in opposition to the formalism of orthodox Lutheran practice. Much of Zinzendorf's belief was formed by his godfather, Philipp Jakob Spener, the early leader of the Pietist movement; in time, Zinzendorf developed the view that Christianity could more effectively be spread by loose collections of believers outside the Lutheran church.

In 1722, Zinzendorf began accepting German refugees at his estate in Saxony. Members of the Moravian Brethren, an independent Christian sect predating the Reformation, were fleeing Catholic persecution in Bohemia and Moravia. The village of Herrnhut, established on his estate, soon attracted not only many Moravians but adherents of various other persecuted sects. Zinzendorf established a common order of worship for the assembled Moravians, Pietists, Separatists, Schwenkfelders, and others, and organized them on the model of family life. A vigorous publishing program issued vast numbers of books, tracts, hymnals, catechisms, and small Bibles.

Under his leadership, the Moravians were the first Protestant body to declare officially that the evangelization of the "heathen" was a duty of the church. From 1732, a broad program of missions began, sending representatives to slave populations and Indians in the West Indies, Greenland, and North America. Before Zinzendorf's death, missionaries also traveled to the Baltic countries, Surinam, North Carolina, parts of South America, the East Indies, and South Africa. Zinzendorf himself traveled to the Caribbean and North America on behalf of the Moravians, as related in part by his Pennsylvanische Nachrichten, a work first published as a series of pamphlets in Philadelphia. In this work, the count tells of a remarkable conference at Germantown in January 1741/2, when he approached all the evangelical Pennsylvania sects with his unifying zeal. In the first of several conferences, Quakers, Mennonites, Dunkers, Schwenkfelders, Separatists, Hermits, members of the Ephrata community, and others delivered opinions and were brought to joint agreement on several resolutions. If Zinzendorf had intended with these meetings to forge a single religious body under Moravian leadership, he was disappointed, but the firm missionary commitment of the Moravian Brethren survived him.

3. Ethnology

Merueilleux et estrange rapport, toutesfois fidele, des commoditez qui s...

1590

-

p. 1

p. 1The town of Secota, as painted by John White, was one of the illustrations used in de Bry's version of Hariot's "Virginia" pamphlet, here shown in its French translation, Merveilleux et Estrange Rapport. The engraving shows the Indian habitations, gardens with tobacco (E) and pumpkins (I), a ceremonial fireplace (K), a guardhouse to spot animals in the cornfield (F), planting distance between cornstalks (H), the place of the ceremonial dance (C), the place of communal dining (D), a place of prayer (B), and the tombs of their rulers (A). White's original watercolor lacks the identifying letters, but labels the three cornfields as showing different stages of growth.

The English edition of Hariot's work is fairly familiar, but the French edition is less often exhibited. Like item number 6 in this catalogue, Hariot's German edition, this volume represents the first book in Theodor de Bry's monumental illustrated series on the Americas. Only with this first work did de Bry attempt to publish French and English editions in addition to those in Latin and German; but it did prove feasible to produce another twelve volumes in uniform Latin and German editions. The de Bry family also issued a similar, splendidly illustrated series to publicize the voyages made to the East Indies, "India Orientalis." The John Carter Brown Library holds complete sets of both series, as well as various subsequent editions

The manners, lawes, and customes of all nations

1611

-

p. 9

p. 9Johann Boemus was a Catholic priest in Ulm, Germany, where he earnestly studied Hebrew language and literature, learning much from the town’s Jewish population prior to their forced departure in 1498. Boemus’s intense interest in other cultures led to a comparative study of customs and mores. This frequently published work, first printed in 1520, was amended as early as 1542 to include American material. From that year, extracts from various sources, including Damião de Góis, Girolamo Giglio, Maximilianus Transylvanus, and Jacob Ziegler, were added to the editions and translations. In 1604, a portion of Jean de Léry’s famous work on Brazil was added to a Latin Boemus edition and both texts were translated into English in 1611. Of the many editions of Boemus, in various languages, only a few contain the Léry extract.

Léry’s original Histoire d’un voyage fait en la terre du Brésil (La Rochelle, 1578) concerned Villegagnon’s attempt to form a French colony in Brazil. Nicolas Durand de Villegagnon, a pupil of Jean Calvin, had advertised his intention to establish a non-creedal colony in Brazil, a sort of spiritual predecessor of William Penn’s city of brotherly love, Philadelphia, a century later. Jean de Léry was one of the French Protestant colonists who answered the call to settlement. Upon their arrival, the Huguenots met instead with persecution. They fled the colony, hiding among the Indians until they were able to escape to Europe. A subsequent report by André Thevet portrayed the Protestants as troublemakers and poor colonists. Léry, who later became a minister at Geneva, published his relation to counter the tendentious misrepresentations he felt had been promulgated by Thevet.

In the course of his account, Léry devoted some time to reporting on the environment and people. The extract that appears in the Boemus (pages 483—502) describes plants, animals, and Indian behavior. The reader learns of such things as the maraca, a dried gourd used as a musical instrument, the ‘boucano’ or barbecue, and the way Indian women carry children about on their backs as they perform other chores. There is also a full explanation of the preparation of manioc as a food and beverage.

Léry describes at length the fondness of the Tupi for a life of nudity, explaining the burdensome inconvenience clothing poses for them. He assures his European readers that, at least after initial exposure, the nakedness of the Indian women is less a “provocation to lust and lasciviousness” than the elegant clothing, hairdressing, and makeup employed by European women. Having placed himself at some peril in his deliberate, reasoned defense, he goes on to cite the story of Adam and Eve, declaring that no one should think him favoring the adoption by Europeans of “this wicked and beastly custom” that he has allowed for by “those wretched and miserable Americans.”

Neundter vnd letzter Theil Americae

1601-1602

-

p. 1

p. 1José de Acosta, a Jesuit missionary, was the first European to approach in a truly objective fashion the question of Indian origins. Having worked closely with native populations in the course of seventeen years in Peru and Mexico, he relied more on experience and observation than on philosophy and tradition. Distancing himself from the conventional theories based on cultural comparisons with ancient races, Acosta instead used the tools of logic, eliminating each theory that would not stand up to reason. The theories involving transatlantic sailings were rejected because the Indians had no compass or lodestone; passage over land or a narrow strait therefore seemed most probable to him. Rejecting also the European notion of the lost continent of Atlantis, he thought the migration of peoples had most likely occurred either by way of Tierra del Fuego, Greenland, or the "Anian" strait then presumed to lie between North America and Asia.

Though not a scientist, Acosta was an acute observer and a clear thinker who practiced restraint in his pronouncements and sought to align his theories with a body of fact. His thinking with regard to the Indians was closely allied with his observations on plants and animals. While providing little in the way of enumeration, he raised key questions about how America could have a thousand different plants and animals unknown to Europe. Much more pointedly than other Spanish observers of New World flora, such as Oviedo or Monardes, Acosta emphasized the tremendous difference between the biology of the New and the Old World. He noted, importantly, that Oviedo's use of Spanish names for "similar" plants masked striking variances. However, as with any theologically-trained thinker of the time, Acosta had to incorporate in his understanding the story of Noah and the Flood. He rejected the idea some proposed for a "second" ark for America. The animals, too, had to have gotten to America by means of a land link or shallow strait.

Acosta's positive contributions to the empirical thinking of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries were especially influential in northern Europe. His De Natura Novi Orbis (Salamanca, 1588), enlarged (Seville, 1590) as Historia Natural y Moral de las Indias, was soon published in Italian (1596), Dutch, German, and French (all in 1598), and English (1604). Exhibited is the German edition of 1601, one of numerous seventeenth-century reprints. The illustration of Aztec ritual sacrifice is drawn from one of Acosta's studies of religious practices in Mexico and Peru.

Warhaftige Historia vnd Beschreibung eyner Landtschafft der wilden, nack...

1557

-

p. 7

p. 7For Europeans, the most repellent practice of indigenous Americans was their alleged anthropophagy. The earliest writers, including Columbus and Vespucci, distinguished timid, peaceful Indian groups from fierce, warlike cannibals. Some modern, revisionist historians have proposed that the yoke of cannibalism was superimposed on the natives by the conquering powers as a means of justifying exploitation, subjugation, enslavement, or annihilation. Nonetheless, detailed, believable accounts of cannibalistic customs among at least some Indian groups can be found in the contemporary printed literature.

One of the most popular early accounts is that of Hans Staden, a German from the town of Homburg in what is now the federal state of Hessen. Staden made two voyages to South America in the mid-sixteenth century, motivated by curiosity about the Indies. On his second visit, while in Portuguese service, he was taken into captivity by the Tupi Indians of Brazil, and for nine months was exposed to their life and customs, as well as to recurrent punishments and threats. Upon his release and return to Europe, he was encouraged to publish two accounts of his experiences, which were accompanied by simple illustrations. The resulting book is one of the earliest and most widely dispersed works on Brazil, having been frequently reprinted and translated.

While among the Indians, Staden continually feared for his life, but particularly of being eaten. He repeatedly turned to his Christian faith for comfort, and utilized it in efforts to calm his fellow prisoners. Staden witnessed various acts of cannibalism, and related in detail the manner of preparation. His imprisonment was abetted by a French trader who believed him to be Portuguese.

The German was finally released through the intercession of other French traders who devised a ruse that touched the sensibilities of his captors. As throughout the affair, it is apparent that those who were eaten by the Tupis were those considered to be their enemies and inferiors, whether the hated Portuguese colonizers or neighboring tribes. The French traders, with whom the Tupinamba maintained friendly business relations, were, as equals, able to negotiate Staden's freedom, despite his early misidentification.

The Warhaftige Historia is the first edition of one of the earliest captivity narratives and an important source for the ethnology of early Brazil. In the year of publication, there were three more German editions, and the book was also published in Latin and Dutch before the close of the century; it continued to be published in Dutch well into the eighteenth century. This work of Protestant piety is striking because of the narrator's sincerity and objectivity.

Narratio regionum indicarum per Hispanos quosdam devastatarum verissima

1614

-

p. 1

p. 1The Spanish thought of their undertakings in the New World as a sort of Holy Mission; Christianity and European civilization were to be brought as gifts to the peoples of America. The sense of rectitude, pride, and self-confidence they felt as a nation was very much like that felt by the great colonial powers of the nineteenth century and the international commercial powers of the twentieth. It was therefore with considerable distress that they received the published reports of Bartolome de las Casas, a priest in Spanish America for many years.

Las Casas, the son of a man who had accompanied Columbus to America, studied law at Salamanca, but became a priest in Hispaniola a few years later. The young missionary soon became involved in what would be a lifetime obsession, his work for native American rights and welfare. Those Indians who had survived the initial conquest had become the virtual slaves of their Spanish colonizers. Las Casas's concern for their plight led to persistent lobbying efforts that were instrumental in winning new, more humane laws for Spain's Indies in 1542. His work necessarily offended existing property interests, and the laws were weakened by amendments. Las Casas opposed the laws' feudal aspect, however, and sought to bring his concerns directly to public attention.

In 1552, Las Casas began the publication of a series of pamphlets, the first of which was entitled Brevissima Relacion de la Destruycion de las Indias. The pamphlets painted in brutal detail what appeared to be nothing less than the extermination of a people, including shocking estimates of lost populations. The priest had come to view the whole colonial enterprise as a vast, morally bankrupt fraud, masking naked avarice with ecclesiastical banners. Las Casas's obsession and convictions deprived him of any vestige of impartiality, however, and he targeted Spanish national character in his propagandizing polemics, exaggerating to an extreme degree in defense of what he felt to be the essential truth. He saw Spain's colonization as an unpardonable offense committed against a sovereign people. Religious conversion and acceptance of Spanish rule should have been free decisions, he argued.

Within three decades, the story told by Las Casas had been printed in Holland, France, and England; it appeared in Latin and German by the end of the 1590s. Italian and many more Dutch editions were printed in the early seventeenth century. Shocking illustrations in some editions fueled not only the righteous indignation of the northern European Protestants and rival Catholic countries, which had an interest in undermining Spanish authority and power, but undoubtedly also fed public fascination with depictions of torment, much as later cinematic purveyors of violent images would do (see fig. ill. 5). Some of the images draw on the tradition of the iconography of Christian martyrdom.

Las Casas's writing became the cornerstone of the Black Legend, that is, the tendency to take the image of Spanish colonial misdeeds as the norm of their behavior. Much of the rest of Europe, predisposed to view Spain as the evil empire of its day, likened the American abuses to the misdeeds of the Inquisition and the crimes committed in the Low Countries during Spain's occupation of them, all aspects of an institutional tyranny.

With the advent of the historical study of disease in the twentieth century, the likelihood emerged that virulent diseases unknown to the New World, such as smallpox, rather than slaughter, had been the primary scourge of the defenseless native populations, wiping out whole areas. Still, some radical intellectuals, focusing on colonialism, contend that the Las Casas accounts were actually representative and demonstrate a pattern that has been carried on up to the present time, especially by repressive Latin American governments and business interests, as native rights are ignored in favor of other objectives.

Abrah: Milii Merckwürdiger Discurss von dem Vrsprung der Thier, vnd Aus...

1670

-

p. 9

p. 9Most writers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries interpreted literally the story of the Flood and Noah's ark. Confronted by the realities of American aborigines and unfamiliar species, some sought to modify the story, suggesting the existence of a second ark, or of a special creation of life in America, or tried to juggle the supposed dating of the Indians' arrival there with the dating of the Flood. The Dutch author, Abraham van der Myl, who was trained in theology, read all the great works on the subject and tried to explain on a Biblical basis, in a volume he wrote at the age of seventy, how life in the New World had come into being. His De origine animalium, et migrationepopulorum (Geneva, 1667) was published thirty years after his death and was translated three years later into the German edition shown (see fig. ill. 6), to which the translator, J. C. Bitterkraut, added some contributions of his own.

Myl fully accepted the idea that details on America could be gathered from the Bible, and that evidence could be found that connected ancient peoples to those in the New World. King Solomon was thought to have sent a shipping fleet to America and built the front of the temple in Jerusalem with Peruvian gold. America was populated, however, by people who passed across a strait and covered the two parts of America in their travels.

Under the influence of rationalism, Myl thought it incredible that the entire world should have been covered by water—even the high mountains of America! And if there were no people there, and thus no sinners, why would Divine punishment have been meted out there? He concluded that not all of the world came under the Flood. Further, he wrote, since the animals in America are without parallel in Europe or Asia, one must conclude either that these animals lived through the Flood, or they would have to have been newly created after it. Because the second theory conflicts with the creation story of Genesis—God's work being complete after the sixth day—there can have been no further creation.

A new voyage to Carolina

1709

-

p. 5

p. 5Lawson, a traveler and surveyor, is best known for his account of North Carolina. The book, which saw four early English editions and two in German, offered a remarkably good account of the natural history of that region and also of the indigenous population and its customs. He described many birds and fish, and a number of mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. His account of no less than 267 different North Carolina species is remarkable when one considers that Carolus Linnaeus, the father of the modern classification of plants and animals, was able to describe for the entire globe only 4,400 species. Lawson's descriptions contain numerous curious observations, as in the case of the skunk: "The Indians love to eat their Flesh, which has no manner of ill smell when the Bladder is out."

Lawson observed the Indians closely, not failing to note the appeal of the women:

"When young, and at maturity, they are as fine-shaped creatures (take them generally) as any in the Universe. They are of a tawny Complexion; their Eyes very brisk and amorous . . . and their whole Bodies of a smooth Nature. . . . Nor are they Strangers or not Proficients in the soft Passion."

His views of Indian languages were less positive. He was distressed by the supposed imperfection of their moods and tenses, judging them "deficient." The widely varying languages of different groups of Indians were seen as a serious detriment to their social development: "Now this Difference of Speech causes Jealousies and Fears amongst them, which bring Wars, wherein they destroy one another; otherwise the Christians had not (in all Probability) settled America so easily as they have done." A six-page glossary of words and expressions in English, Tuscarora, Pamlico, and Wacco suggests the sorts of exchanges that occurred between a contemporary Englishman and a Carolinian.

On returning to England and publishing this work, Lawson was named surveyor-general of North Carolina. He also became involved in a plan that settled a colony of 600 Germans and Swiss-Germans in the region, resulting in the foundation of New Bern. In 1711, while on an expedition in North Carolina, Lawson was seized by Tuscarora Indians and put to death, probably by tortures he had himself described.

Mœurs des sauvages ameriquains, comparées aux mœurs des premiers temps

1724

-

p. 7

p. 7A Jesuit missionary to the Iroquois in Canada prepared this comprehensive study of aboriginal customs, which is represented here by its first edition. A defender of Indian rights, Lafitau worked especially hard against the trade in brandy. The book was important enough to be translated into Dutch in 1731, as De zeden der wilden van Amerika. Lafitau's work discusses such questions as the Indians' origin, essentially covering all the origin theories, their religion, government, marriage customs, education, village occupations, hunting and fishing methods, the activities of women, war, intertribal relations, commerce, games, medical knowledge, death and mortuary customs, and language. In the origin essay, he seeks to establish a link with ancient peoples, providing many sources of comparison; this theme continues throughout the book.

Even on the subject of games, Lafitau takes pains to relate his observations to supposed similarities with early peoples. In discussing lacrosse, "le jeu de Crosse," he cites examples in Classical writings, including Pollux and Martial, to suggest that the Indians have preserved the pastimes of ancient Europeans; another ball game of relative simplicity is similarly linked to ancient Rome.

Ceremonies et coutumes religieuses des peuples idolatres

1723-1728

-

p. 1

p. 1The present volume, the sixth of an eight-volume series on the religious ceremonies and customs of peoples throughout the world, focuses on those of the West Indies, or America. Because it was edited by Jean Frederic Bernard, the publisher, authorship has often been attributed to him. It is, however, a compilation from the writings of a number of French authors. The collection was translated into Dutch and published from 1727 to 1738 as Naaukeurige beschryving der uitwendige godtsdienstplichten... van alle volkeren der waereldt; an English edition, The religious ceremonies and customs ... of the known world, was printed at London between the years 1731 and 1739.

Some of the illustrations in this original French edition are rather fanciful, placing Indians in settings that suggest ancient Roman architecture and statuary or traditional European carpentry, furniture, and decorative wooden floors. Bernard's collection treats such individual topics as combat, sacrifices, religion, funeral customs, romance, and marriage, touching on many of the same themes as Lafitau, but drawing from disparate sources for their interest value. Rather than the concentrated didactic work of a single scholar-priest, it is a diverse collection of materials drawn from many writers, forming something like an early coffee-table book. Indian groups throughout the known American territory are treated.

In the chapter "Ceremonies nuptiales des peuples de la baie de Hudson, du Mississippi & du Canada," one of the sources Bernard draws on is "Hontan, or Louis Armand de Lorn d'Arce, baron Lahontan, who traveled widely in New France, and reported on his observations in Nouveaux voyages... dans I'Amerique septentrionale (first published. The Hague, 1703). Lahontan has been described as a freethinker who had little regard for the clergy. His work appears to be authentic, being in many respects borne out by others writing independently on the same subjects. It has also been recognized, however, that his stories were sometimes embellished. Lahontan used the full freedom of a secular viewpoint, considering Indian customs on their own merits, free of orthodox value judgments. His popular writings were published largely in the Netherlands, where the press was subject to fewer strictures, although a few editions appeared in London and Protestant German cities. None were published in France.

Lahontan did not hesitate to consider the full extent of the question of romance. He even suspected the motives of Jesuit priests, suggesting that girls and young women not be exposed to their interviews unescorted. He relates in some detail how the Indians of Canada conduct their affairs after dark (see fig. 111.8). The young man enters the hut well-covered, bearing a small torch lit from the embers of the campfire. The female may reject him by withdrawing more deeply into the covers. If she should extinguish the flame, he lies down next to her. The English expression "carrying a torch," to describe being in love, derives from this description.

Lahontan is especially mystified by the high level of sexual independence which seems to precede marriage. With expressions of astonishment he relates, in an early English translation, "They'll suffer anybody to sit upon the foot of their bed and have a little chat; and if another comes in an hour after, that they like, they do not stand to grant him their last favours." Lahontan assures the reader that the young girls drink the juices of some roots either to prevent conception or to terminate a pregnancy. It was said of Caribbean natives early in the sixteenth century that they also possessed herbal agents for inducing abortions. He notes that a girl will not be able to get married if she has a child.

4. Science

La historia general delas Indias

1535

-

p. 9

p. 9Fernandez de Oviedo y Valdes, known to the English-speaking world as Oviedo, was named overseer of mines in Hispaniola in 1513, an office he assumed the following year. It was a position that afforded him an excellent opportunity to observe and report on all things found in the Spanish Indies. Oviedo crossed the Atlantic at least a dozen times and lived in America for more than twenty years, advancing to the governorships of Cartagena and Hispaniola. The early explorers had routinely listed and described the events and phenomena they were exposed to, but it was Oviedo who for the first time approached his subject in a historical context in his 1526 "De la natural hysteria" and his 1535 "Historia general," a work commissioned by Emperor Charles V.