Overview

Background and Timeline of Publication

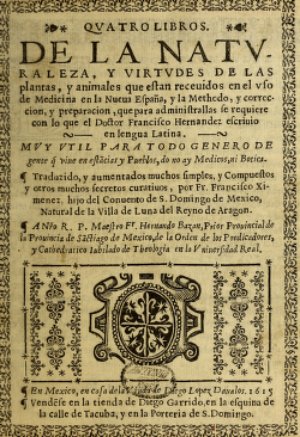

Quatro libros. De la naturaleza, y virtudes de las plantas, y animales q...

1615

-

p. 7

p. 7This is the title page of the Quatro libros de la naturaleza published in 1615 by Francisco Ximénez, a friar at the Convent of San Domingo de Mexico. The title (and the text itself) emphasizes medical and pharmaceutical uses of the plants and animals recorded by Hernàndez. Despite Recchi's intense edits, Ximénez writes here that the text is based on "what the doctor Francisco Hernández wrote in Latin."

-

p. 14

p. 14In this section of the note to the reader, Ximénez explains that Hernández gained his knowledge of medicinal plants and animals in Mexico through experience, and that his Latin text, written for the king of Spain, was later edited by Nardo Antonio Recchi from Naples. (None of Hernández's handwritten copies left in Mexico survived.) Interestingly, Ximénez adds that he used Hernández's recommendations in a hospital in Oaxtepec and found them effective.

What is the Nova Plantarum?

[Title page] Rerum medicarum Novae Hispaniae thesaurus

1651-1700

-

p. 1

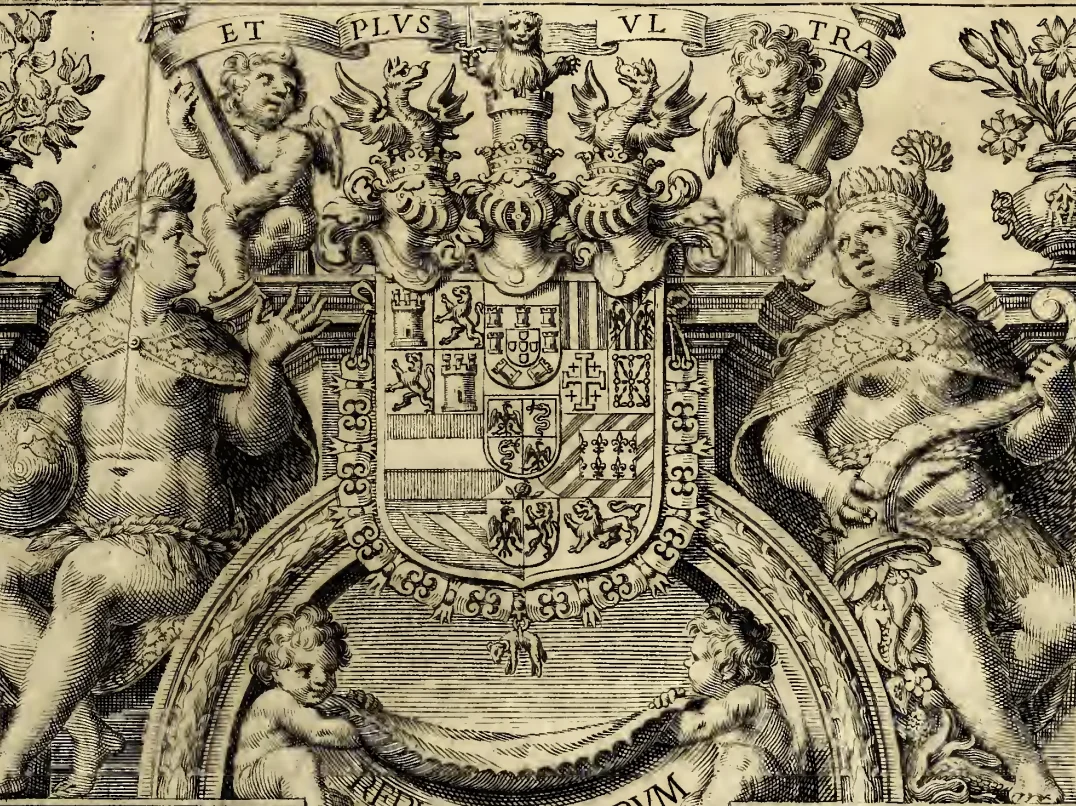

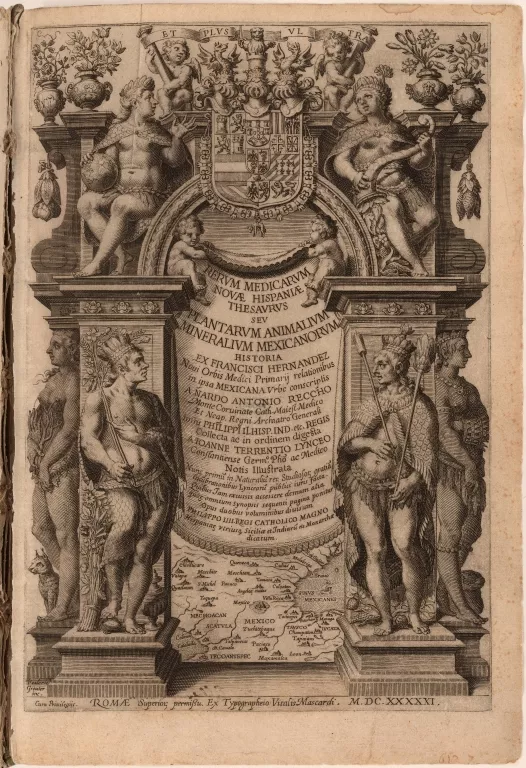

p. 1As mentioned in the "Nova plantarum" essay, this famous title page is an ornate imagining of Spanish domination over American abundance. In the center, atop the Spanish monarchy’s coat of arms and held up by two putti, is the motto "Et plus ultra" (“And farther beyond"), suggesting a metaphor of "discovery" as it contrasts with the ancient story of the Pillars of Hercules, that warned sailors to go "ne plus ultra" ("no further beyond").

-

p. 1

p. 1Two depictions of Indigenous people flank the Spanish king's coat of arms, the one on the right holding a cornucopia representing abundance, and the other on the left holding a globe representing Spain’s global imperial aspirations. They are surrounded by decorated vases containing plants native to the Americas.

-

p. 1

p. 1Four more European depictions of Indigenous people, clad in feather skirts and capes, stand around the title of the book. Some hold golden jewelry, displaying the continent’s mineral wealth, and others hold more native American plants, showing its natural wealth.

-

p. 1

p. 1A lynx sits at the feet of one of the Indigenous people, representing the Accademia dei Lincei, named for the sharp-eyed lynx to reflect the scientific prowess of the academy.

-

p. 1

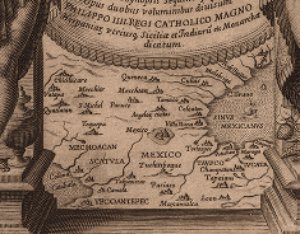

p. 1Below the title sits a map of Mexico, with a combination of Indigenous and Spanish place names.

[De Copalliquahuitl Patlahoac, seu Arbore Copalli latifolia, Copallifera II.]

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Here, Hernández gives the plant's Nahuatl name, Copalliquahuitl Patlahoac, then its Latin name, Copalli latifera. In the Latin name rests part of the Nahuatl name, copalli, meaning incense, demonstrating how the European Hernández relied on, but rarely acknowledged, Nahua knowledge to create this compendium. It is a fitting name for a vibrant autumnal plant smoked with tobacco by many Indigenous American cultures.

-

p. 1

p. 1This plant is most likely what is commonly known in English as the shining sumac, largely used in the United States for landscaping. The processes of colonization have removed its medicinal properties (what Hernández sought) and its ceremonial ones (one of its uses to the Nahua).

Contributions to European Knowledge

1. Tigre Messna. 2. Tlacocelotl. 3. Itzcuintepotzotli. 4. Istrice Messno...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

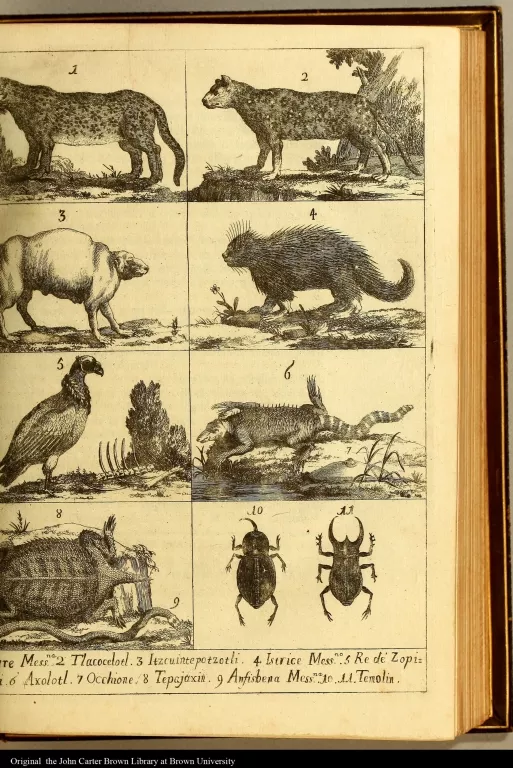

p. 1Here a smaller but otherwise almost exact copy of the "axolotl" (iguana) print in Francisco Hernández's Nova plantarum appears, also labeled as an axolotl. Other books between the publication of the 1651 Nova plantarum and the 1780 publication of the Storia antica del Messico use more accurate salamander or axolotl images to refer to their axolotls, meaning that Clavigero relied specifically on Hernández, not that axolotls were regularly mislabeled in early modern Europe.

-

p. 1

p. 1Like the "axolotl" below it, this porcupine is nearly identical, if smaller, to the image of the hoitztlacuatzin, the "New Spain porcupine," depicted on p. 322 of the Nova plantarum. The image in the Nova plantarum is clearly related to the print of the same animal in Juan Eusebio Nieremberg's Historia naturae maxime peregrinae (p. 154), which was based on the Nahua paintings that Hernández commissioned while in Mexico.

Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium Mexicanorum historia

1651

-

p. 338

p. 338Hernández's entry on the axolotl, a Mexican salamander, uses a woodcut print of an iguana, despite his description clearly referring to an axolotl.

-

p. 993

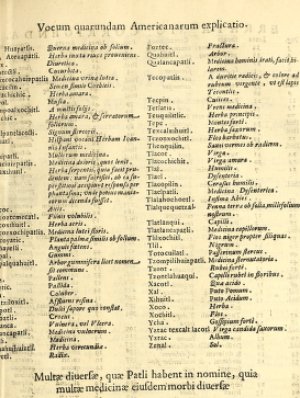

p. 993This is a brief glossary of transliterated Nahuatl terms related to medicine and natural knowledge for which Hernández has provided what he understood as the Latin language equivalent.

-

p. 344

p. 344This print of the Mexican hairy dwarf porcupine is a clear copy of the one in Juan Eusebio Nieremberg's Historia naturae maxime peregrinae (1635), proving that the two printmakers used the same source material – the Nahua paintings commissioned by Hernández during his years in Mexico.

-

p. 650

p. 650This two-headed calf, whose dissected body appears in prints on the previous pages, came from the collections of Federico Cesi and was the subject of public, courtly scientific debate. Johannes Faber, a physician and member of the Accademia dei Lincei included his discussion of this bizarre natural phenomenon in the Nova plantarum, not as part of Hernández's text but as a creature that, in its strangeness, could teach about natural history.

-

p. 819

p. 819This print, also by Johannes Faber, is reminiscent of Cesi's two-headed calf in its strangeness. However, unlike the calf, the amphisbaena, a two-headed serpent, had a history as a mythical creature in western Europe. Faber claims here to have seen an image of a real one, and thus includes it in his natural history addendum to Hernández's encyclopedia.

-

p. 838

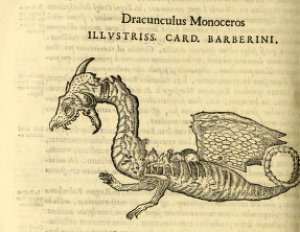

p. 838Cardinal Francesco Barberini, who was also a member of the Accademia dei Lincei, had in his museum collection this mummified dragon, gifted to him by the king of France. Again with a description written by Johannes Faber, this fantastical creature was included in a book otherwise focusing on Mexican natural knowledge in order to bring attention to the Cardinal's investment in scientific knowledge production. It seems likely that Faber and Barberini knew this dragon would catch both the eye and the imagination.

-

p. 7

p. 7Two depictions of Indigenous people flank the Spanish king's coat of arms, the one on the right holding a cornucopia representing abundance, and the other on the left holding a globe representing Spain’s global imperial aspirations. They are surrounded by decorated vases containing plants from the Americas.

-

p. 7

p. 7Four more European depictions of Indigenous people, clad in feather skirts and capes. Some hold golden jewelry, showing the continent’s mineral wealth, and others hold more native American plants, showing its natural wealth.

-

p. 7

p. 7A map of Mexico, with a combination of Indigenous and Spanish place names.

-

p. 7

p. 7A lynx sits at the feet of one of the Indigenous people, representing the Accademia dei Lincei, named for the sharp-eyed lynx.

-

p. 62

p. 62Hérnandez gives the plant's Nahuatl name, Copalliquahuitl Patlahoac, then its Latin name, Copalli latifera. In the Latin name rests part of the Nahuatl name, copalli, meaning incense. A fitting name for a vibrant autumnal plant smoked with tobacco by many Indigenous American cultures.

-

p. 62

p. 62This plant is now commonly known in English as shining sumac, largely used for landscaping.

Print, Elites, and the Imperial Project

Ioannis Eusebii Nierembergii Madritensis ex Societate Iesu ... historia ...

1635

-

p. 166

p. 166Scholars agree that many of the prints in this book were based on paintings commissioned by naturalist and physician Francisco Hernández, author of the Nova plantarum (1651), in the 1570s. This image of the Mexican hairy dwarf porcupine appears in an very similar form in the Nova plantarum. This shows how Hernández's images made their way into early modern European natural knowledge before the official publication of his encyclopedia.

Indigeneity and the Monstrous

Bibliography

Editorial Note

Project Creator(s)

- Michal Loren

- Rachel Moss

- Emily Monty

- The John Carter Brown Library