1. Controlling Cartographic Knowledge in Iberoamerica

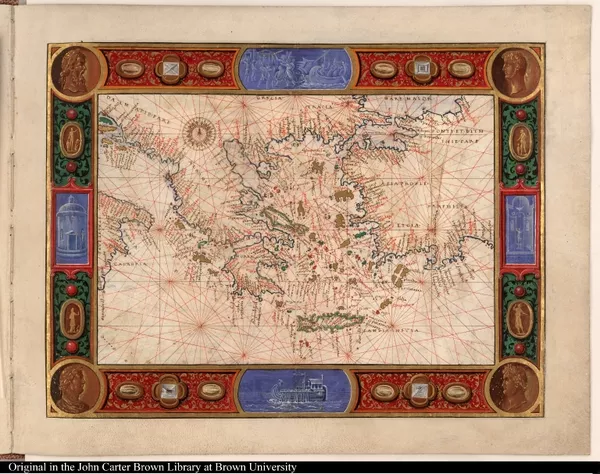

[Map of Greece and the Aegean Sea, including part of Turkey]

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1A Connected World

The world map in the Agnese Atlas, one ofthe jewels of the JCB collections, celebrates the first circumnavigation voyage by show-ing the new route connecting the Atlantic tothe Pacific and achieving the long-desiredgoal of opening a Western route linking the ‘Old World’ to the Far-East. The track of the circumnavigation forms an unbroken line connecting for the first time previously separate regions of the globe.

La carta uniuersale della terra ferma & Isole delle Indie occide[n]tali ...

1534

-

p. 1

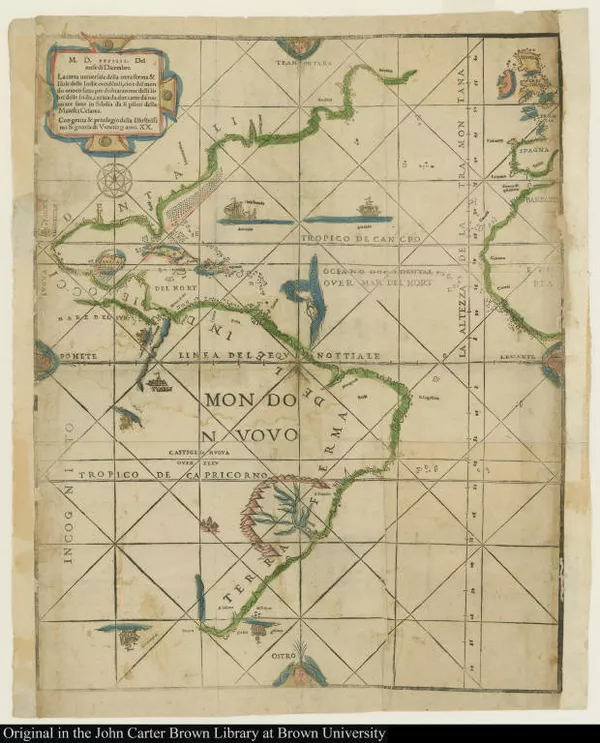

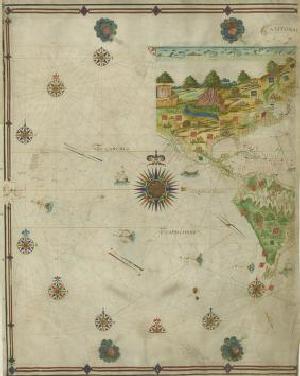

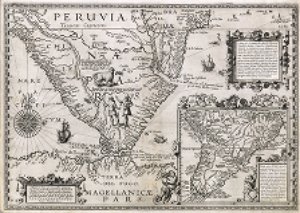

p. 1America before the Strait of Magellan

Before the opening of the Southern route to the Pacific Ocean, Europeans lacked knowledge about large portions of the West coast of the Americas. This very rare printed map, commonly called the “Ramusio Map,” illustrates the extent of Spanish control in the Americas and of Spanish cartographical knowledge in 1534, within fifteen years of the completion of Magellan’s circumnavigation.

Magellan’s name marks the strait while unknown lands on the west coasts are designated as “incognito.”

Los Indios acometen à Los Religiosos ÿ otros ÿ ponen fuego à la casa ò a...

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Magellan: A Controversial Figure?

Magellan, a Portuguese navigator, led the circumnavigation voyage under the patronage of the Spanish Crown. As a result, nobles and bureaucrats of both countries would raise suspicions about the navigator's loyalty and would have competing claims on Magellan's legacy. This rivalry, which nonetheless cemented the Iberian control of South America, causes disputes even today.

[Early representation of Newfoundland, Lower California, the Amazon, and...

1545

-

p. 1

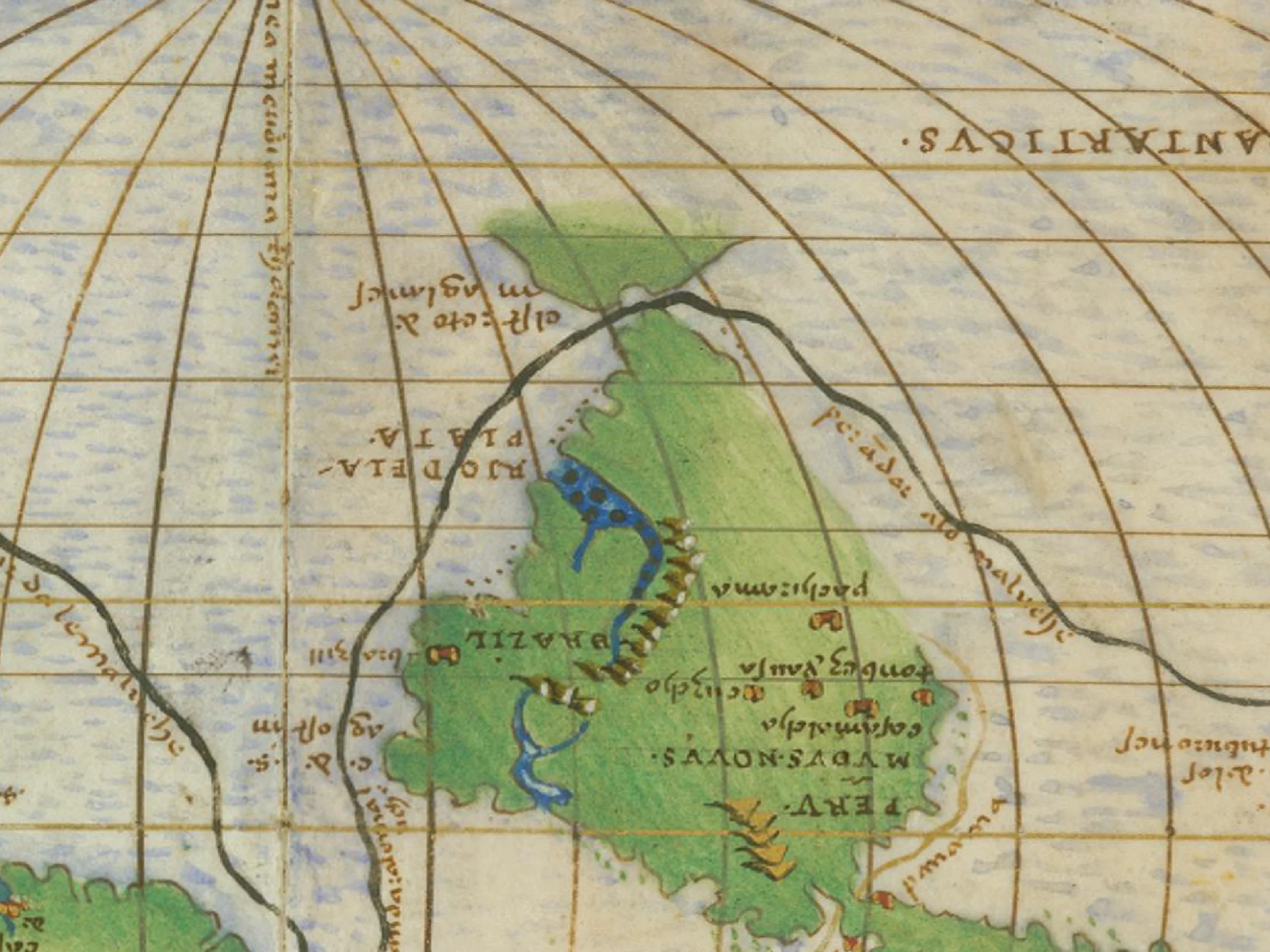

p. 1The "Spanish Lake"

When Magellan sailed through the strait, he claimed it for the Spanish Crown, which came to control both passages to the Pacific Ocean: the overland route in Panama and the newly found maritime route in the south. As a result, the Pacific Ocean was known as the "Spanish Lake" in the sixteenth century. This highly-colored manuscript map is one of very few pre-1550 maps that depicts the momentous geographic discoveries in the Americas made by Europeans. The Spanish coat of arms liberally scattered throughout the region indicates the extent of Spanish claims, both terrestrial and maritime.

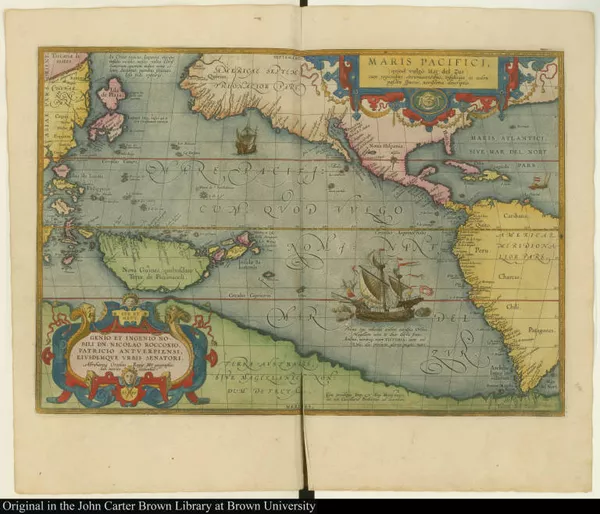

Maris pacifici, (quod vulgò Mar del Zur) cum regionibus circumiacentibus...

1589

-

p. 1

p. 1An Interconnected World

Spanish dominion in the Pacific Ocean led to renewed inter-imperial competition for access to the markets of East Asia. Abraham Ortelius' 1591 map illustrates the new connections between the West Coast of the Americas and Southeast Asia that the Strait of Magellan facilitated, underscoring to other Europeans the potential advantages that successful navigation of the route could bring.

2. From “Spanish Lake” to Global Sea

Franciscus Draco nobilissimus angliae eques, rei nauticae ac bellicae pe...

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1A Spanish Lake No More: Drake and the Second Circumnavigation

Since crossing the Strait of Magellan proved to be extraordinarily difficult, Spanish authorities believed that the risks of navigating the passage would prevent rivals from hazarding their own circumnavigations. However, when English privateer and slave trader Francis Drake was able to cross the Strait successfully in 1578 and went on to circumnavigate the globe, he demonstrated that this was a misconception. The map in this French edition of Drake's account of his voyages illustrates the route he took.

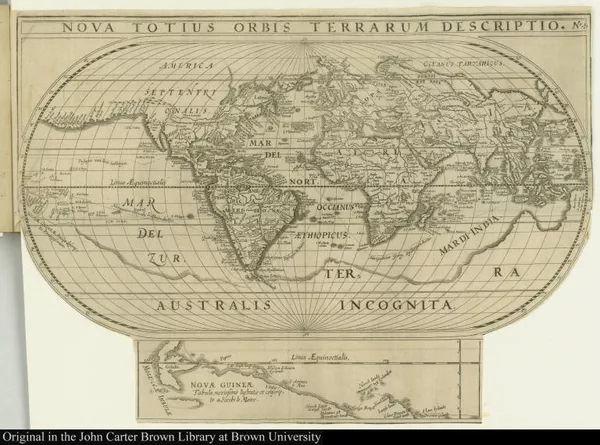

Nova totius orbis terrarum description. No. 1

1619

-

p. 1

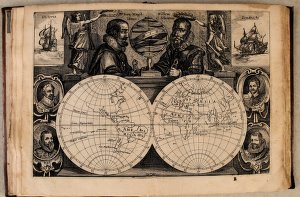

p. 1The Dutch Worldwide Scheme

In addition to their ongoing battles to gain independence from Spain in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Dutch attacked Spanish power in the Americas. Their main objective was to control access to the Pacific Ocean, thus challenging the Spanish monopoly and opening a new commercial route to Asian markets. Joris van Spilbergen was the Dutch admiral who commanded the Dutch East India Company fleet that successfully sailed through the Strait in 1614. This engraving from his journal depicts the flora and fauna of the region and includes a scene in which the Dutch amicably greet indigenous peoples.

Iournal ou description du merveilleux voyage de Guilliaume Schouten, Hol...

1618

-

p. 15

p. 15Opening the Two "Locks" to the South Sea

In 1616, two Dutch navigators, Jacob Le Maire and Willem Schouten, sailed around Cape Horn, successfully identifying a second path (or "lock") to the Pacific Ocean by crossing a strait located to the south of the Strait of Magellan, which they named "Le Maire Strait." With this discovery, the Dutch, who had already mastered the navigation of the Strait of Magellan, came to have complete access to the Pacific. This engraving celebrates Magellan and Schouten, the navigators who opened the two "locks," alongside other noted mariners, including Cavendish, Drake, van Spilbergen, and van Noort.

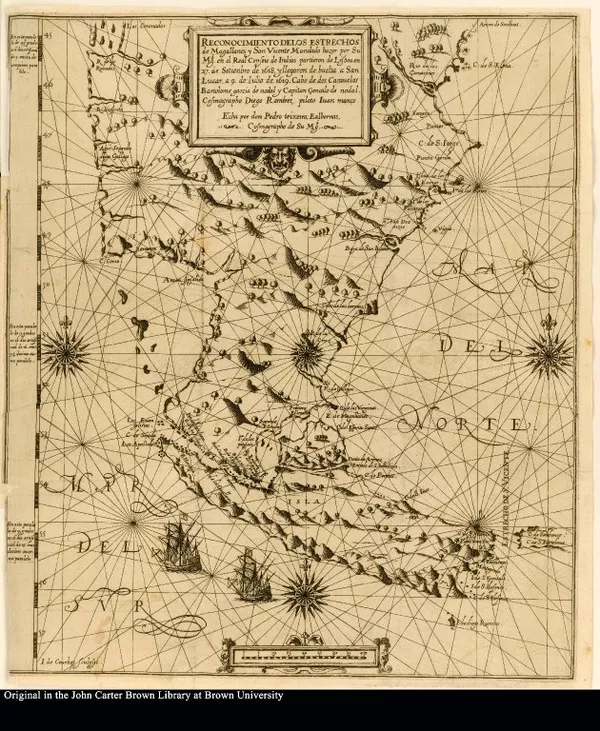

Reconocimiento delos estrechos de Magallanes y San Vicente Mandado hazer...

1621

-

p. 1

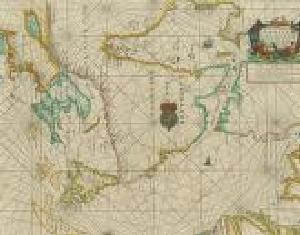

p. 1The Spanish Empire Strikes Back

While the Dutch celebrated the discovery of a new route to the Pacific Ocean, Spanish officials were frustrated that the Dutch did not disclose the location of this new passage. An expedition commissioned by the Spanish Crown and led by the brothers Bartolome and Gonzalo García de Nodal successfully reconnoitered the Cape of Good Hope in 1618-9, discovering the "Le Maire Strait." The brothers renamed the strait the "Estrecho de San Vicente," as this map in Bartolome García de Nodal's 1621 journal confirms.

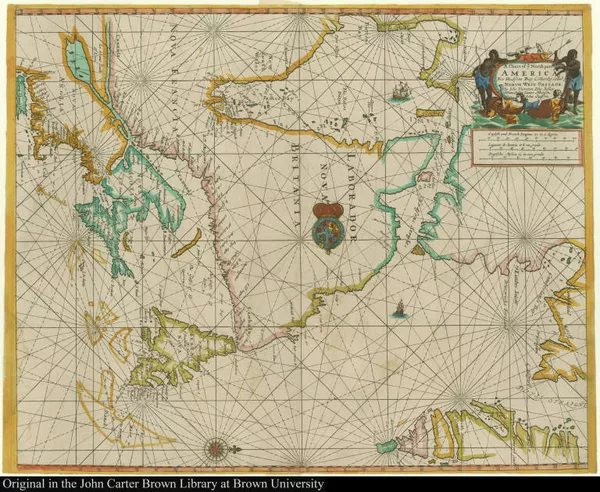

A Chart of ye North part of America For Hudsons Bay Com[m]only called ye...

1677

-

p. 1

p. 1English Endeavors

English buccaneers, traders, and royal agents also sailed to the southernmost corner of the Americas in the seventeenth century. Like their Dutch predecessors, the English sought to expand their influence at the entrance to the Pacific Ocean along the western American coasts and into Asia. They did this by attempting to establish a trading post near the Strait of Magellan. Sir John Narborough's 1669-71 expedition to open trade to Chile was a failure, except for the cartographical record of his voyage through the Strait of Magellan that Narborough produced upon his return to England, displayed here.

3. Europeans imagine America’s southernmost lands

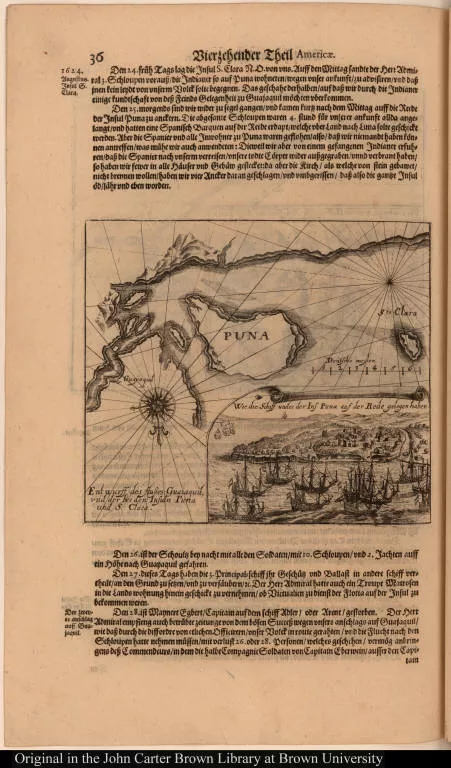

[Guayaquil and the isla Puná]

1601-1650

-

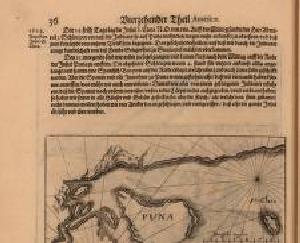

p. 1

p. 1The South American Imaginary

The transmission of knowledge about the new route around South America had an immediate impact on European print culture. This influential 1631 map engraved by Hondius and published by De Bry presented Patagonian giants, grotesque sea monsters, and scenes of cannibalism as defining elements of the Americas. It integrated these southern peculiarities into a hemispheric perspective and highlighted the mysterious southern reaches of the continent in an inset map of a "Terra Australis Incognita," strongly identified with Magellan.

View of a Town in the Island of Terra del Fuego.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1The Giant "Patagones"

The average height of European men in the early modern era was 5.3 feet, while men of the Tehuelches, one of the indigenous people of the Southern Cone, were enormous compared to Europeans, measuring approximately 6.5-7 feet tall. Magellan named the Tehuelches "Patagones," probably referring to their big feet ("patones") and possibly influenced by the widely-read chivalric romance "Primaleon," which featured a monstrous giant named Patagón. The legend of Patagonian giants rapidly spread throughout Europe and the Americas and proved enduring. Commodore John Byron's eighteenth-century travel account of his circumnavigation included this illustration of an enormous Patagonian woman.

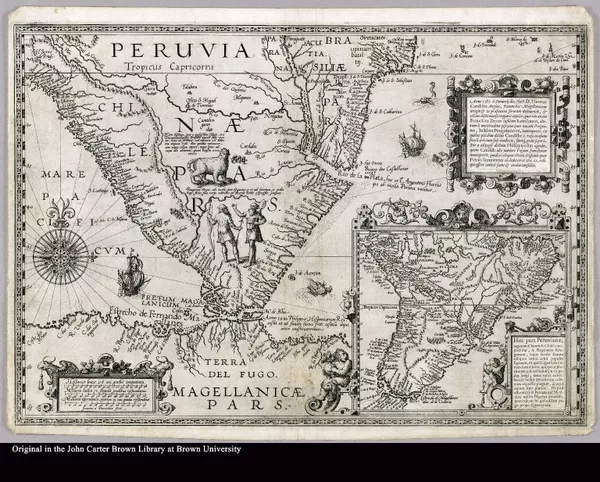

Haec pars Peruvianae, regiones Chicam & Chile[nsem] complectitur, & Regi...

1592

-

p. 1

p. 1Giants in a Southern World

In Plancius' magnificent c. 1592 map of Peru, muscular Patagonian giants, standing below a sloth, are represented as both (or perhaps either) a club-bearing savage and/or a Europeanized man bearing a bow and arrow.

-

p. 1

p. 1All of these figures are the inhabitants of a fantastical southern world made up of two large landmasses. One was South America, and the other, across the narrow Strait of Magellan, was an expansive second southern continent marked by European settlements named after Magellan, and whose northern reaches are named "Tierra del Fuego."

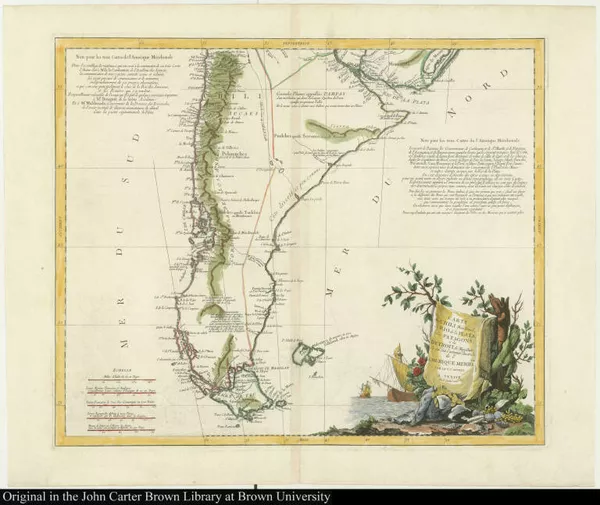

Carte du Chili Méridional du Rio de la Plata, des Patagons, et du Détroi...

1779

-

p. 1

p. 1The Legendary City of Caesars, Peopled by Shipwreck Survivors

The Strait of Magellan is one of the most difficult maritime passages in the world, which caused many shipwrecks in Magellan's time and later. These tragic maritime voyages fueled the belief in the existence of a wealthy city populated by the survivors of these failed expeditions. The idea of a "City of Caesars" founded by survivors of a 1540s shipwreck endured to appear in D'Anville's 1779 map of Chili, which identifies a location in northern Patagonia inhabited by "Cesares," a mixed-race people whose predecessors included Spaniards coming from Chili in the 1550s.

4. Beyond imagination: American realities

Journael ende historis verhael van de reyse gedaen by oosten de straet l...

1646

-

p. 1

p. 1The Araucanos as Mirror-Image of the Dutch

The Dutch saw the "Araucanians," indigenous peoples from Chile, as potential allies against the Spaniards, since both peoples resisted Spanish conquest. This European-American alliance sought to end Spanish rule in Peru, and the cooperation worked out until the Dutch asked the Araucanians [Huilliches] for gold. This image depicts indigenous Chileans, accompanied by their llama, conversing with Dutchmen; it is taken from the journals of Hendrick Brouwer who commanded the fleet sent by the Dutch West India Company to seize the Spanish gold mines of Valdivia, Chile, in 1642.

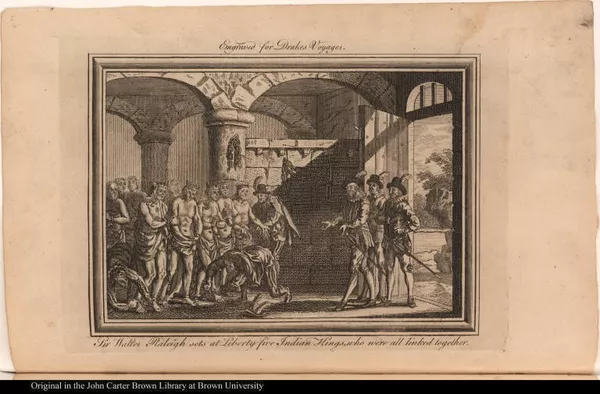

Sir Walter Raleigh sets at Liberty five Indian Kings, who were all linke...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

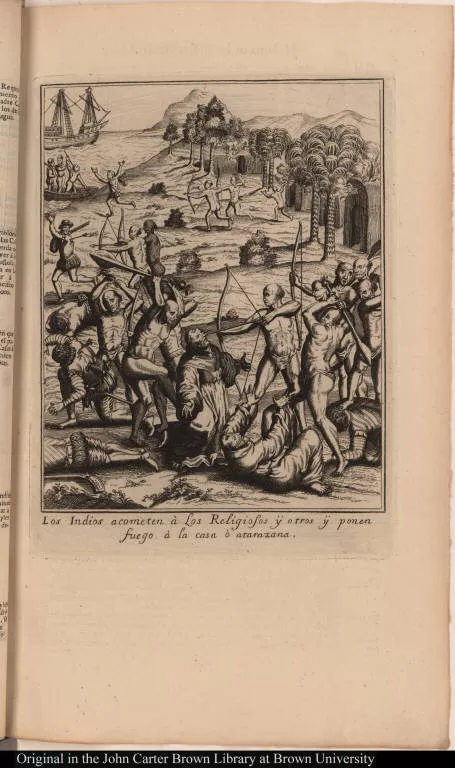

p. 1Violent Encounters

Between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries, increasing imperial competition over the region of the Strait and, centuries later, deliberate policies of genocide led to the annihilation of many indigenous populations. Wars, diseases, and famines decimated the Yaghans, Tehuelches, Selk'nam, and Kawésqar, and survivors were treated inhumanely. For instance, captives from the last three groups were put on display in the "human zoo" at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1889. The print here refers to a 1599 Dutch massacre of a community from the Tierra del Fuego, in which there was a single adult female survivor.

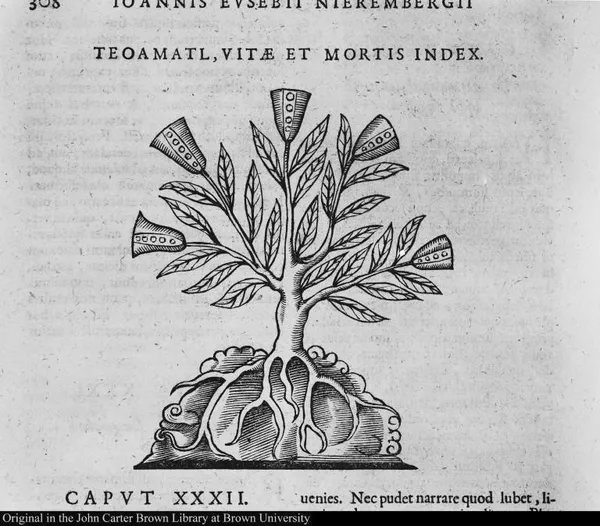

Teoamatl, Vitae et Mortis Index

1601-1650

-

p. 1

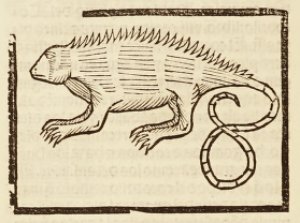

p. 1New (Dangerous?) Fauna

Europeans had their own vulnerabilities, and the unfamiliar and often alarming fauna of the Strait fed their worst anxieties about the harm that these new environments could bring them. Even well-known animals, like the armadillo, were perceived as dangerous.

La historia general delas Indias

1535

-

p. 222

p. 222In 1557, Fernández de Oviedo described armadillos as “belligerent animals” that wielded their urine against Europeans when threatened, and the illustration depicts them as menacing and aggressive.

Description du penible voyage faict entour de l'univers ou globe terrestre

1602

-

p. 41

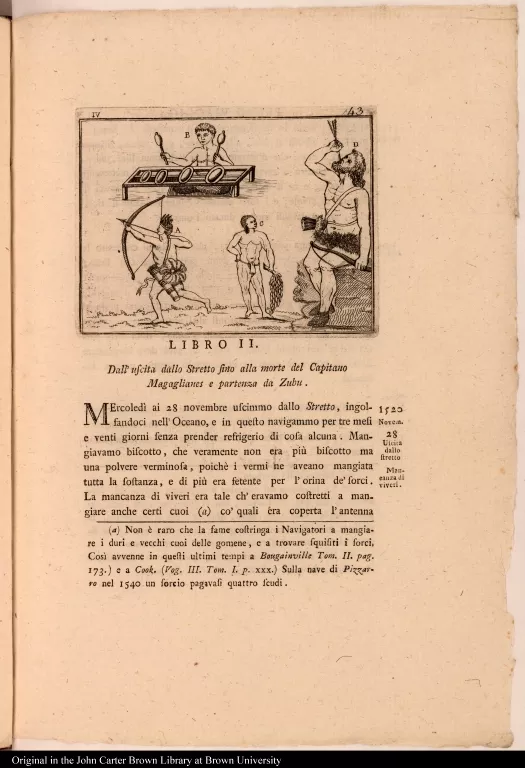

p. 41Everyday Life in the Strait of Magellan

There were several indigenous communities living in the Strait: the Tehuelche, the Selk’nam, the Kawésqar, and the Yaghans. In the 19th century, they were collectively known in the English-speaking world as "Fuegians."

Lord Anson Mort à Londres en 1762.

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1These groups were nomadic seafarers and hunter-gatherers living in Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. Some of their daily objects, such as those on display here, were collected by European and North American explorers and ended up in Western museum collections.

5. The southern passage and early modern globalization

Kaisei chickyu bankoku zenzu

1780

-

p. 1

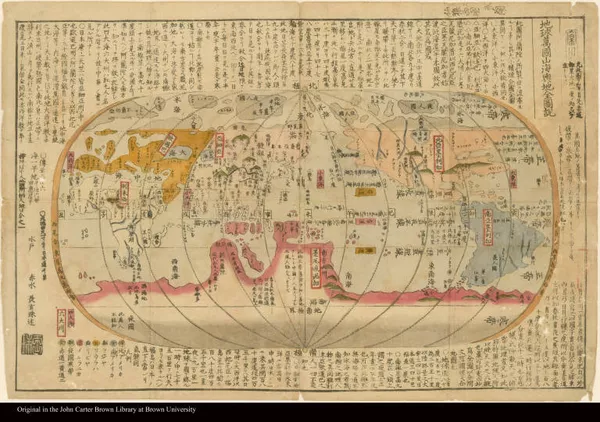

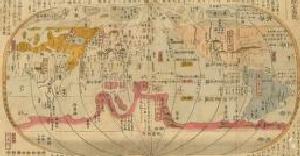

p. 1The view from the east

The Southern route allowed for the growth of interactions between Asia and the Americas, and, as a result, new cartographic representations of this interconnected world appeared in places beyond the realm of European empires. The '(Kaisei) Chikyû bankoku sankai yochi zenzusetsu' map, or the "(Revised) Complete Explanatory Illustration of the Countries of the World and Mountains and Seas" by Nagakubo Sekisui (1717–1801), a famed Japanese cartographer, was probably based on Matteo Ricci's and Dutch maps. This Japanese map is considered to be one of the first examples of "scientific" cartography produced in Japan.

[Indians of South America]

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1A globalized world

Although globalization is often regarded as a modern phenomena, it has its roots in the sixteenth century. This 1800 edition of the 1522 Pigafetta map of the first circumnavigation route reveals the enduring practical and symbolic relevance of the Strait of Magellan for an ever more interconnected and interdependent world.

Credits

Editorial Notes: Items Pending Integration

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library