1. France and Spain on the North American Coast

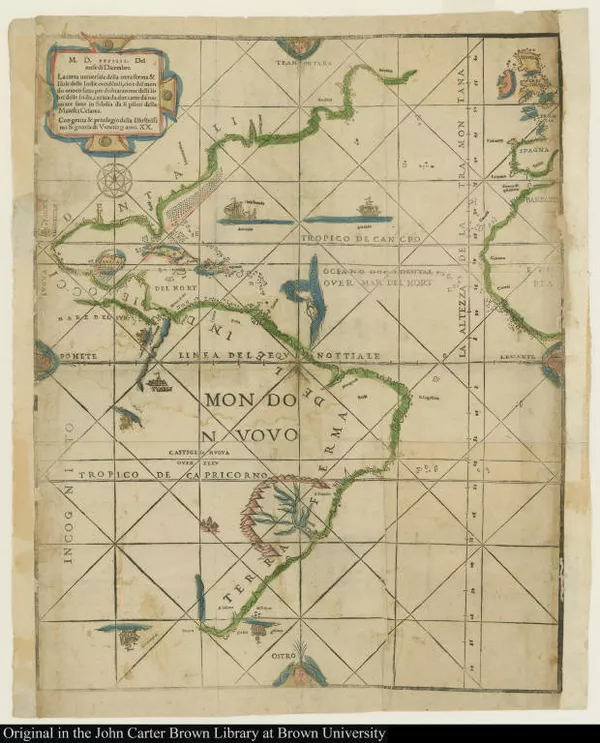

La carta uniuersale della terra ferma & Isole delle Indie occide[n]tali ...

1534

-

p. 1

p. 1The Spanish View of North America

The Ramusio map of 1534 was derived from the official Spanish cartographic record of New World discoveries, the padron real. On this map, "licentiato ailon" refers to Lucas Vazquez de Ayllón (ca. 1475-1526) who received a license from the Spanish crown to explore the coast of Spanish "Florida" in 1520. After an initial reconnaissance voyage, he returned to plant a colony in 1526 and his settlement, San Miguel, was located where the English would later establish Jamestown. Vazquez de Ayllón died of a fever four months after his arrival and his quarreling colonists soon abandoned the settlement. "Stevã Gomez" recognizes the 1525 reconnaissance voyage by Estevan Gomez along the New England coast. These references are reminders of active Spanish interest in the American coast well to the north of present-day Florida.

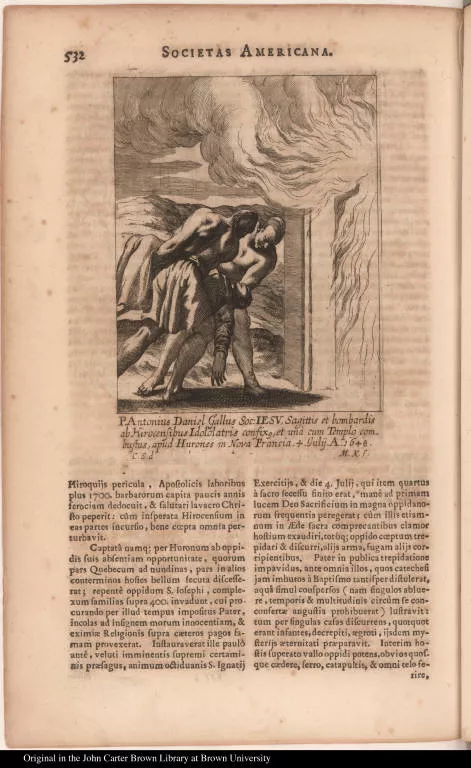

P. Antonius Daniel Gallus Soc: Iesu, Sagittis et bombardis ab Hirocensib...

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Attempted Spanish Settlement on the Chesapeake

In 1561 Paquiquineo, a high-born Paspahegh youth from Chesapeake Bay, joined a party of Spanish explorers. Treated as an aristocrat, he eventually wound up in Spain, converted to Catholicism, and was baptized Don Luis after his sponsor, Viceroy Don Luis de Velasco. In 1570, he returned to North America in the company of Father Joannes Baptista de Segura and his companions, who were on a mission to the Indians in the Chesapeake Bay area called by the Spaniards the Bahia de Santa Maria de Ajacán. After the missionary party landed, Don Luis renounced the Christian faith and returned to his people. The Fathers protested and Don Luis, apparently angered by their harangues, murdered the missionary party. The Paquiquineo/Don Luis story suggests the complicated issues of cultural convergence and conflict that were an integral part of the encounters between Americans and Europeans in this early period.

[Fort Caroline]

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1France and Spain Face Off in the Southwest

Sixteenth-century French attempts to establish a presence on the southeast coast of North America tell a sad story from beginning to end. In 1562 Jean Ribaut led a group of Huguenots to Parris Island, South Carolina, and erected Fort Caroline. The venture was short-lived. Ribaut returned to France for reinforcements and his colonists, unable to support themselves, followed a few months later. Two years later, René de Laudonnière made another colonization attempt further south near present-day Jacksonville, Florida. That colony was destroyed by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, who had been entrusted by Spain with the task of driving the French from the region and establishing a colony in Florida to defend Spanish claims.

Obra nueuamente compuesta, en la qual se cue[n]ta, la felice victoria qu...

1571

-

p. 7

p. 7Spanish Celebration in Verse

This account in verse of the destruction of the French colony is the only contemporary printed record of the Spanish/French conflicts from the Spanish point of view. Midcourse it becomes a promotion tract for a Spanish colony that Pedro Menéndez de Avilés was trying to establish in Florida as a buffer against French and English incursions.

2. Stirring up English Interest

The arte of nauigation

1561

-

p. 1

p. 1The Translators—Richard Eden, 1521?-1576

By mid-century Spanish travel accounts and navigation manuals began to appear in English translation. Stephen Borough, chief pilot for the Muscovy Company, which had been established in 1555 to expand English trading networks, visited Spain in 1558 and was impressed by the maritime expertise and organization he saw there. He persuaded the Company to support the translation into English of Martín Cortés’s official Spanish treatise on navigation. The translator was Richard Eden, who had held a post as a Treasury official and was probably an historian of the Muscovy Company as well.

Ioyfull nevves out of the newe founde worlde

1577

-

p. 1

p. 1The Translators—John Frampton, fl. 1577-1596

In 1559 John Frampton, an English merchant resident in Seville, fell into the hands of the Spanish Inquisition. Years elapsed before he was able to make his escape and return home, bankrupt and disheartened. To solve his financial problems Frampton turned privateer and raided Spanish shipping. His most effective long-term revenge, however, was the translation of six Spanish books that focused the attention of Englishmen on the wealth of the Indies that they had, by default, allowed to enrich Spain and Portugal. The Joyfull newes of the title shown here refers to the anticipated profits from the cultivation and sale of New World commodities such as the potato, sarsaparilla, and sassafras (a supposed cure-all)—a strong financial motive for Sir Walter Raleigh and others to undertake the colonization of North America.

The principall nauigations, voiages and discoueries of the English natio...

1589

-

p. 1

p. 1The Compilers—Richard Hakluyt, ca. 1551-1616

Richard Hakluyt's major work, The Principall navigations, shown here, is so celebrated that it often overshadows his long and active role in making the literature of discovery available to his countrymen. From 1580 to his death in 1616 he was directly or indirectly responsible for twenty-eight works on geography and exploration. He cast his net widely and developed a network of scholars, publishers, and explorers in England and abroad with whom he exchanged information and ideas.

Diuers voyages touching the discouerie of America

1582

-

p. 1

p. 1The Compilers—Richard Hakluyt, ca. 1551-1616

Humphrey Gilbert was granted a patent to colonize regions of America to the north of Spanish claims in Florida and Mexico, but was having difficulty raising funds. Richard Hakluyt’s Divers voyages was intended as propaganda for the venture. In order to familiarize his public with the region, Hakluyt translated original documents, provided accounts of prior English voyages to the New World, and supplied descriptions of the land from a variety of sources. The work was introduced with a preface that stated Hakluyt's views on the larger aims his country ought to pursue: (1) the revival and advancement of national glory through trade, (2) the colonization of North America as a stepping stone to Asian markets and as a place of opportunity for England’s destitute, and (3) the development of British sea power through the education of her seamen.

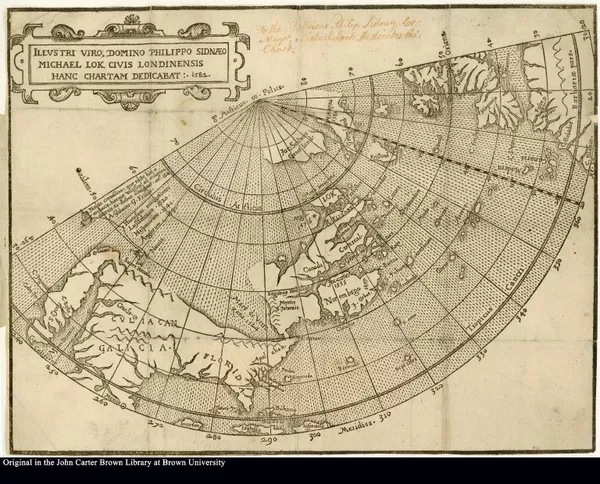

Illustri viro, domino Philippo Sidnaeo Michael Lok civis Londinensis han...

1582

-

p. 1

p. 1Lok's provocative North American geography suggests an easy connection between the Atlantic Ocean and the markets of Pacific Asia.

The original writings & correspondence of the two Richard Hakluyts

1935

-

p. 1

p. 1Richard Hakluyt's Colonial Design

Hakluyt's Discourse was written in 1584 as a result of his association with Sir Walter Raleigh, who was making plans for a colonial establishment in North America. Addressing this work to Queen Elizabeth, Hakluyt explained how an effective English presence depended upon the solid backing of the Crown. Mass emigration, the establishment of several centers of settlement, and the creation of a multi-level society to transplant the seed of English culture were measures recommended by Hakluyt to avoid expensive and tragic failure. He also underlined the political advantage of a secure English foothold in North America to counter the Spanish menace. This was a private diplomatic document, not published during Hakluyt's lifetime, and it is difficult to assess its contemporary impact.

3. The Beginning of the Virginia Venture

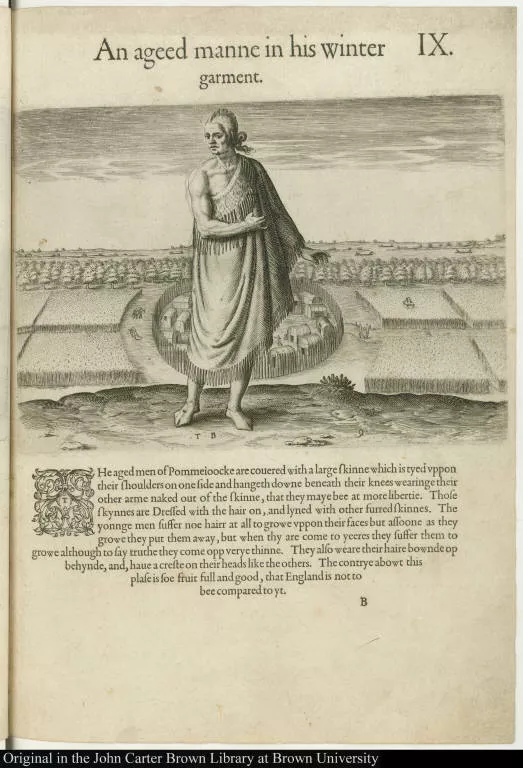

An ageed manne in his winter garment.

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1The Roanoke Outpost

Queen Elizabeth had granted Sir Humphrey Gilbert a patent to plant a colony in North America but he had died at sea on his second attempt. In 1584 Gilbert's half-brother, Walter Raleigh, took over the charter and sent out a reconnaissance expedition of his own, which explored the Outer Banks of North Carolina and Roanoke Island looking for a site that could support a settlement and serve as a base for English privateers to prey on Spanish shipping. Roanoke was chosen on the advice of the Portuguese pilot Simon Ferdinando, who was familiar with the area from his earlier service with Spain. The next year Raleigh sent out a colonizing expedition that included the artist John White and the scholar Thomas Hariot, whose reports and drawings gave Europeans their first view of the American inhabitants of Virginia and their culture.

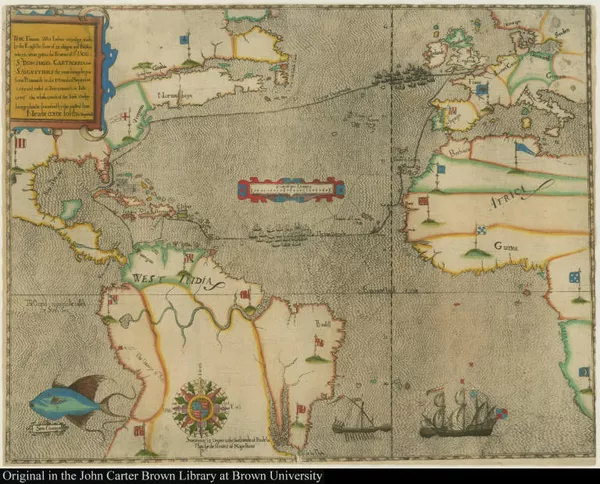

The Famouse West Indian voyadge made by the Englishe fleete of 23 shippe...

1589

-

p. 1

p. 1Drake to the Rescue

In 1585, with the official support of Queen Elizabeth, Sir Francis Drake set out to terrorize the Spanish in the West Indies by attacking their cities and capturing treasure. On the way home, Drake stopped at Roanoke, where he discovered the settlers in grave straits following a harsh winter. Unloading the "several hundred" passengers he had picked up in the course of his Caribbean adventures—African slaves, South American Indians, and galley slaves (including Europeans and Moors)—Drake made room on his ships and took the Roanoke settlers back to England. No one knows what happened to the West Indian passengers so unceremoniously left behind at Roanoke.

Postscript to the Lost Colony

4. John Smith and Jamestown, 1607-1609

A true relation of such occurences and accidents of noate as hath hapned...

1608

-

p. 7

p. 7Christopher Newport, one of the captains who had transported the colonists in 1607, returned to Virginia to resupply the colony the following year. Smith gave him a report on what had transpired since their arrival and probably a map as well, which showed the extent of the colonists’ explorations to date. The map has been lost, but Smith’s report was eagerly received and printed (without his permission) for an audience hungry for the first news of the venture. Smith’s report didn’t mince words about what he thought were the sources of the colony’s problems. To be sure, there were elaborate diplomatic dances and skirmishes of wits between the American natives and the ever-more-desperate English, but the colonists’ inability to set aside rank and status to work together for the common good was especially destructive.

"The Indians, thinking us neare famished, with carelesse kindness, offered us little pieces of bread, & small handfuls of beanes or wheat, for a hatchet or a piece of copper."

"At this time were most of our chiefest men either sicke or discontented, the rest being in such dispaire, as they would rather starve and rot with idleness, than be persuaded to do anything for their own reliefe without constraint."

A good speed to Virginia

1609

-

p. 27

p. 27Ethics of Colonization

As word of problems within the colony itself and between the colony and the Native Americans began to filter back to England through official and unofficial letters and reports, several authors began the process of questioning or defending the legitimacy of the colonization process itself.

“…there is no intendment to take away from them [the Indians] by force that rightfull inheritaunce which they have in that countrey… wee desire not, neither do wee intend to take anie thing from them, … but to compound with them for that we shall have of them: and surelie except succession and election, there cannot bee a more lawfull entrance to a kingdome than this of ours."

A sermon preached in London before the right honorable the Lord Lawarre,...

1610

-

p. 1

p. 1"Christianitie for their souls ..."

[We give them] "such things as they want and neede, and are infintely more excellent than all wee take from them: and that is

1. Civilitie for their bodies

2. Christianitie for their suls:

The first to make them men:

the second, happy men."

The historie of travaile into Virginia Britannia

1849

-

p. 1

p. 1"Chapt. 5. A true description of the people."

William Strachey, Secretary of the Virginia Company, spent close to two years in Virginia. This compendium, which he wrote for the benefit of the Company, combines information about his experiences on the Chesapeake with a determined justification of English claims to North America. Strachey here suggests that a prophecy of foreign invasion, which was revealed to Powhatan by his priests, could explain much of the American leader's suspicion of the settlers.

The manuscript shown here was copied in the nineteenth century from the original document in the British Library. Before the availability of cameras and photocopy machines, libraries and collectors would routinely pay to have important texts hand-copied.

A map of Virginia

1612

-

p. 8

p. 8Smith’s great map of Virginia was not published until 1612 in the book shown here, which was an expanded version of the True relation of 1608 and a showcase for Smith’s wide-ranging curiosity and powers of observation. The information on the map was gathered on Smith’s reconnaissance voyages in the summer of 1608—the crosses on the map show the extent of English exploration, while geographic detail about the land beyond the crosses was provided by Native Americans. This map had a long life and was not superseded until Augustine Herrman’s map of the Chesapeake was published in 1673.

Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies

1623

-

p. 1

p. 1The Hurricane of 1609

In June 1609, the Virginia Company sent out five ships and a new governor, Sir Thomas Gates, who was given absolute power to institute martial law and bring order and progress to the struggling settlement. But the fleet was dispersed by a hurricane and the ship with the governor was shipwrecked on Bermuda. The remainder limped into the Chesapeake and attempted to oust John Smith, but without the presence of the new governor and his official authorization Smith refused to step down. The impasse between the rival factions was broken when Smith, badly injured in a gunpowder explosion, returned to England in October, never to return to Virginia.

The storm in which Governor Gates and his men were thought to have been lost inspired Shakespeare's Tempest, which was first performed in London in 1611. Shakespeare made use of several Virginia-related details—Caliban's refusal to continue to provide food for Prospero reflected similar tensions in Virginia between the colonists and the Native Americans—and much of the play's language recalls the words of those who had experienced, and lived to write about, the great storm.

A true declaration of the estate of the colonie in Virginia

1610

-

p. 9

p. 9The Winter of 1609/1610: The Starving time.

By the fall of 1609 the strong-willed John Smith had returned to England leaving in place a government of hurricane survivors who lacked the official papers necessary to legally govern. The settlement, wracked by internal dissension and external harassment by Powhatan, barely made it through the winter. Meanwhile, in London, unaware that Gates had survived the hurricane, the Virginia Company attempted to deal with the bad news that their newly appointed governor had perished. In this pamphlet the Company defends the legality and future profitability of the Virginia colony and announces the appointment of a replacement governor, Thomas West, Lord de la Warre, whose projected arrival at Jamestown in that spring with supplies and reinforcements would immediately turn the struggling colony around.

5. A Second Chance for Jamestown

For the colony in Virginea Britannia

1612

-

p. 1

p. 1Military Regime, 1610-1618

Lord de la Warre realized that the survival of the colony depended on the re-establishment of order. His commission as Captain General authorized him to attack the colony's enemies, which he did with vigor. This list of laws covers virtually all aspects of life in the colony.

29. No man or woman (upon paine of death) shall runne away from the Colonie, to Powhatan, or any savage weroance whatsoever.

31. What a man or woman soever, shal rob any Garden, publike or private, being set to weed the same, or wilfully pluck up therein any root, herbe, or flower, to spoile and wast or steale the same … shall be punished with death.”

Nevves from Virginia

1610

-

p. 1

p. 1"God will not let us fall"

In verse, Rich celebrates the deliverance of Sir Thomas Gates from the hurricane and the Virginia colony from the failure predicted by its detractors.

"And to th' Adventurers thus he writes,

Be not dismayed at all:

For scandal can not doe us wrong

God will not let us fall.

Let England know our willingnesse,

For that our worke is good.

Wee hope to plant a Nation,

Where none before has stood."

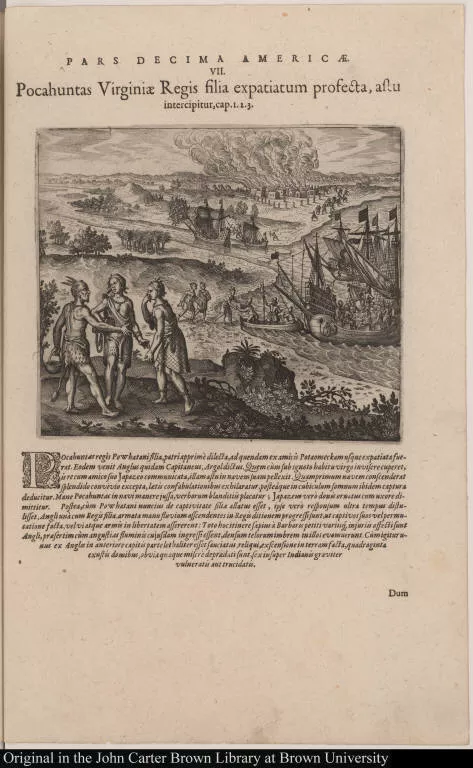

Pocahuntas Virginiae Regis filia expatiatum profecta, astu intercipitur,...

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1Pocahontas Kidnapped

Hostilities between the Americans and the Virginia colonists escalated steadily. In the spring of 1612, Capt. Samuel Argall was trading for corn and heard that Powhatan's daughter was visiting a local chief. With the help of the chief's brother and his wife, Pocahontas was lured on board Argall’s vessel and taken to Jamestown, giving the English leverage to exact a promise of peace from Powhatan in return for her safety. Pictured here is Pocahontas facing the Native American couple (holding their rewards) who lured her into the English trap.

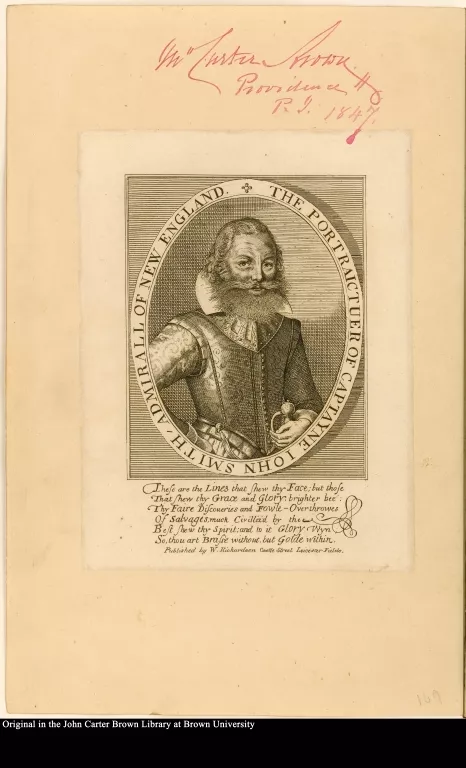

The Portraictuer of Captayne Iohn Smith Admirall of New England

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1Pocahontas / Matoaka / Rebecca Rolfe

Pocahontas never returned to her people. She converted to Christianity, was baptized Rebecca, and married the Virginia planter, John Rolfe, in 1614. After giving birth to a child they named Thomas, the Rolfe family returned to England where they caused a stir in London. Pocahontas fell ill at the beginning of their trip back to Virginia in 1617, died, and was buried at Gravesend, England. John Rolfe returned to Virginia, remarried, and died in 1622. Their son, Thomas, was raised in England by an uncle and returned to Virginia in 1620.

The image on the left was engraved by Simon van de Passe (ca. 1595-1647) from a drawing of Pocahontas taken from life. It was added to Smith's Generall historie by a nineteenth-century book collector who wished to "improve" the status of his edition.

6. Settlement Encouraged

A declaration of the state of the colony and affaires in Virginia

1620

-

p. 31

p. 31Supply List for Virginia

The Company began to send over thousands of new settlers. This pamphlet lists supplies sent to the colony in 1619, as well as the delivery list of 1620. It also provides the names and the amount invested by each "adventurer" (i.e., investor) in the Virginia project.

The inconveniencies that have happened to some persons which have transp...

1622

-

p. 1

p. 1What to Pack?

In the scramble to send large numbers of people to Virginia on short notice costly mistakes were made. Many arrived without proper supplies, food, or clothing, and colonists were often sent at the wrong time of year, in the spring instead of the fall. The warm seasons were the times of greatest mortality on the Chesapeake and many "unseasoned" newcomers died shortly after their arrival.

Americae pars decima

1619

-

p. 105

p. 105Idyllic Vision of Virginia

Overly optimistic written and pictorial descriptions of the country lured the unwary by presenting Virginia as a kind of "no work required" land of milk and honey.

The Portraictuer of Captayne Iohn Smith Admirall of New England

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1Strained to the Breaking Point

Pocahontas’s marriage to John Rolfe in 1614 bought peace for a time, but the influx of English settlers beginning in the summer of 1618 strained English/Native American relations to the breaking point. As they took up tobacco cultivation the settlers began to occupy prime agricultural lands along the James River, which disrupted native life at a time when leadership was in flux following the decline of Powhatan. When Powhatan died in 1618, his brother Opechancanough took control of the empire and was disturbed by what he saw. Aside from the inexorable English encroachment on Indian lands, Opechancanough was particularly concerned by Christian proseletyzing aimed at Indian children, many of whom were susceptible because they worked on English farms.

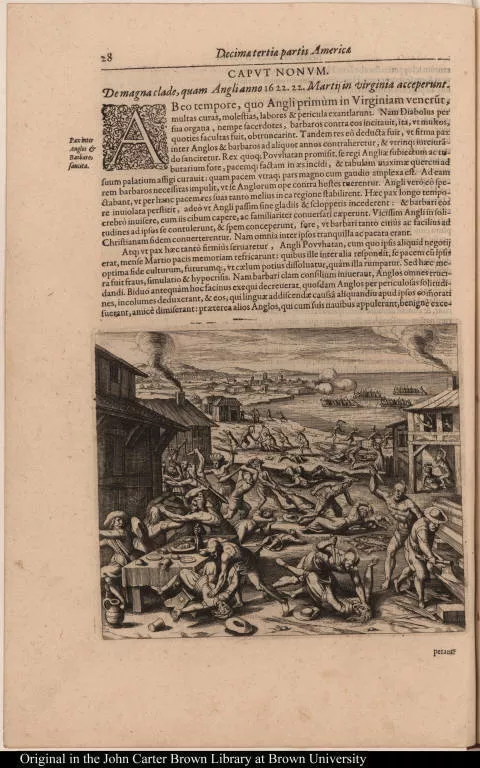

[De magna clade, quam Angli anno 1622. 22. Martiij in virginia acceperunt.]

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1The Indians now realized how threatening an established and expanding English presence would be to their way of life. Undercurrents of hostility came to a head on March 22, 1622, with the massacre of the colonists around Jamestown. Some plantations received last-minute warnings from Indian friends, but few English managed to escape. The massacre put a damper on English settlement for a decade.

A declaration of the state of the colony and affaires in Virginia

1622

-

p. 43

p. 43Aftermath of 1622

English pamphlet-writers reacted to the news of the massacre with horror. Waterhouse said that the colonists were too friendly with the Indians and had been lulled into a false sense of security. Here he lists the names of the 347 English dead and gives his views on the way to deal with the Indians. After March 1622, the English in Virginia embarked on a program of guerrilla warfare against the Native Americans that would last a decade.

“Because the way of conquering them is much more easie than of civilizing them by faire meanes, for they are a rude, barbarous, and naked people, scattered into small companies, which are helps to victorie, but hinderances to civilitie: besides that, a conquest may be of many, and at once.”

A plaine path-way to plantations

1624

-

p. 126

p. 126Marriage among the Colonists

“If they [unmarried colonists] will marrie, they shall not easily finde with whom, unlesse it be with the natives of those countries, which haply wil be nor handsome nor wholesome for them, certainly profitable and convenient (they having has no such breeding as our women have) it cannot be.”

7. Virginia Commodities

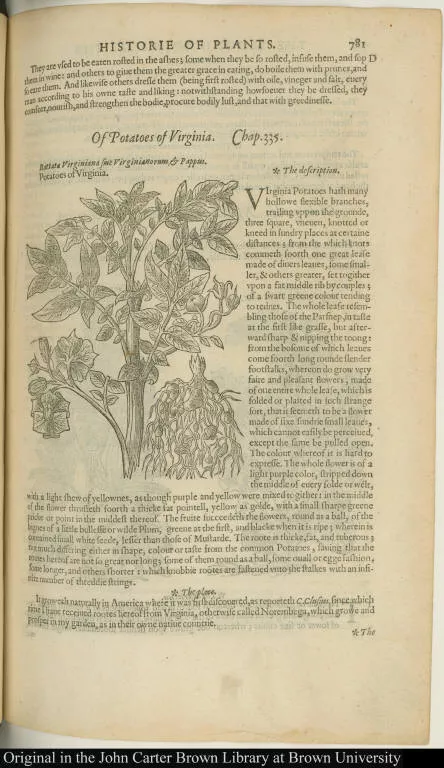

Battata Virginiana sive Virginiarnorum & Pappus. Potatoes of Virginia

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1Potatoes

This is the first published picture of the white potato (as distinguished from the sweet potato, also native to America), a plant that eventually became a staple of European diets. In 1585 one variety of potato was bought to England by Sir Francis Drake, who had encountered them in his raids on Spanish outposts in the Caribbean–it was on this trip that he stopped at Virginia and brought the Roanoke colonists home. Perhaps this is the origin of Gerard's mistaken notion that the white potato was native to Virginia; on the other hand, it may have been his desire to flatter Queen Elizabeth by introducing this new food plant as a product of her namesake colony.

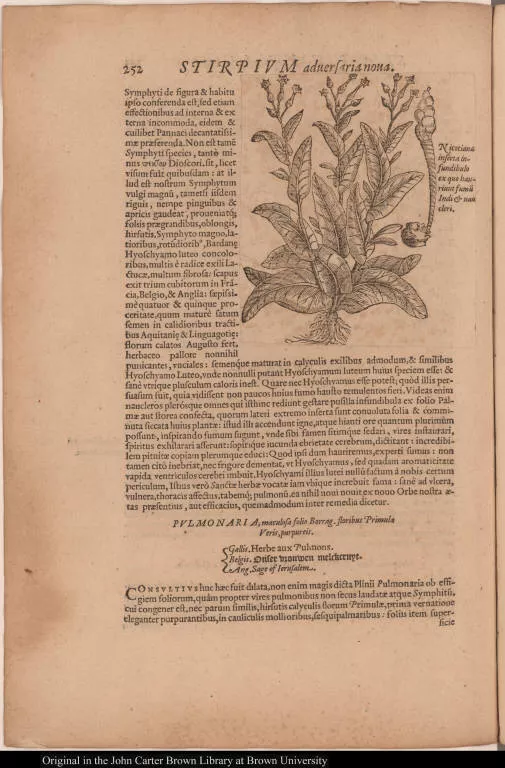

Nicotiana inserta infundibulo ex quo hauriunt fumu˜ Indi & naucleri.

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1Tobacco

By 1569, tobacco was familiar in English gardens, but it was Spain that supplied the herb in the quantity required to satisfy the demand for recreational smoking in England. In the early imagery and writing about tobacco it is often impossible to tell which of the two American species is being described. Brazil was the origin of Nicotiana tobacum, which by the contact period had spread to the West Indies; Mexico was the origin of rustica, which had spread naturally to areas east of the Mississippi and north along the Atlantic coast.

Early English settlers in Virginia considered the rustica too harsh, but the milder Nicotiana tobacum was introduced from the West Indies by John Rolfe in 1612. By 1616, the majority of Virginia plantations were farming tobacco. The Company was not happy about this turn of events and continued to campaign for diversification, but accepted the reality that tobacco cultivation was essential to getting the colony established. It was, however, never supposed to be anything but a temporary solution.

In the text, the authors describe a type of "funnel" in which tobacco was smoked, but the illustration appears to be some kind of exaggerated cigar made from twisted leaves.

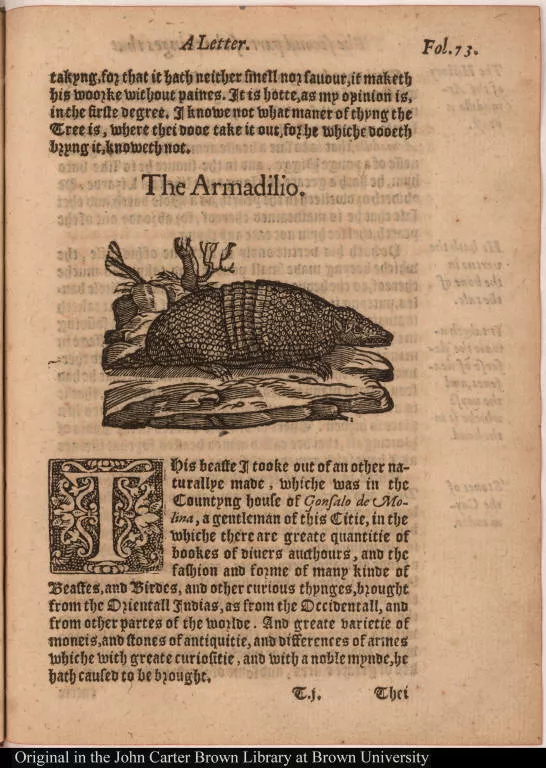

[The Armadilio.]

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1Tobacco

Frampton's translation from the Spanish of this work by Nicolas Monardes was the first in the English language to illustrate the tobacco plant, although it is unclear whether the plant pictured is Nicotiana rustica or tobacum.

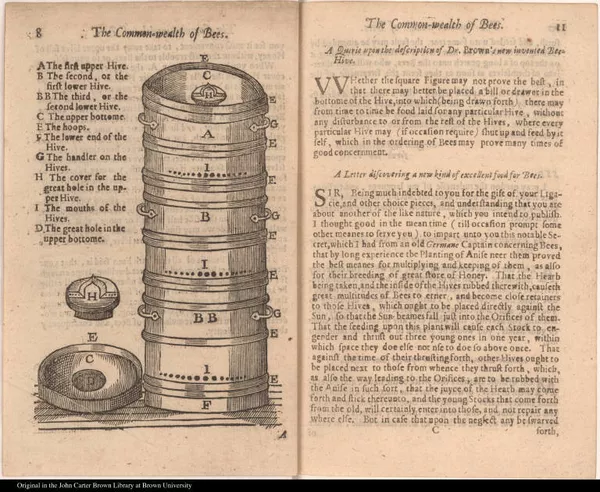

[Bee Hive]

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Bees

There are conflicting statements about when European honeybees were first brought to North America, but there is no doubt that escaped domestic bee—called by Native Americans "white man's flies"—spread rapidly ahead of the colonists as they moved west. Without the honeybee, many European crops could not be grown, a fact that confronts our agricultural system today as it copes with the still-mysterious condition known as "colony collapse disorder" that has resulted in abnormally high die-offs of honeybee colonies in the United States.

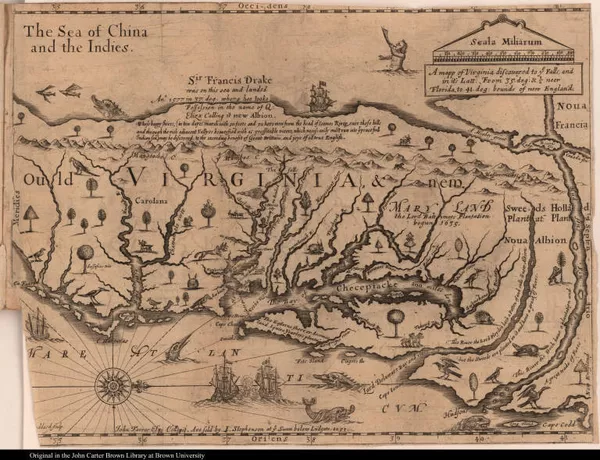

A mapp of Virginia discouered to ye Falls, and in it's Latt: From 35 deg...

1651

-

p. 1

p. 1Sawmills

Instead of burning off all the wood as land was cleared for agriculture, sawmills made it possible to recycle trees into useful and exportable products.

Obseruations to be followed, for the making of fit roomes, to keepe silk...

1620

-

p. 1

p. 1Prices Current for Virginia

"A valuation of the commodities grown and to be had in Virginia: rated as they are worth."

Among the products listed are clapboards at thirty shillings a hundred, honey at two shillings a gallon, and beeswax at four pounds a hundredweight.

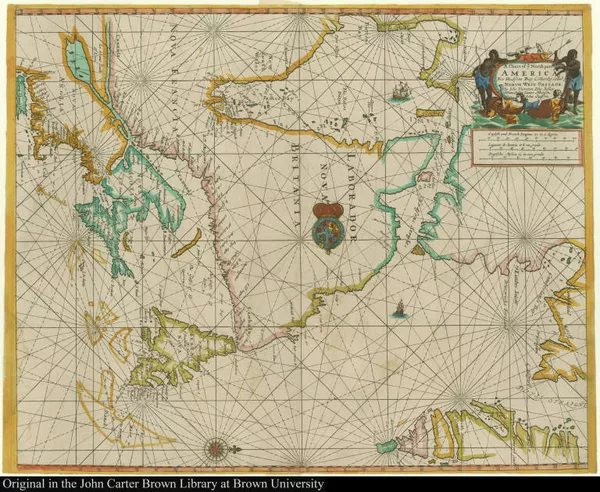

A Chart of ye North part of America For Hudsons Bay Com[m]only called ye...

1677

-

p. 1

p. 1Promotional Map

John Farrer and his daughter, Virginia, were actively involved in attempts to develop the American silk industry. Williams's book extols the virtues of Virginia, and the section about the benefits of silk production was most likely supplied by Virginia Farrer. In fact, the map itself (with north to the right) could be considered a tool to encourage emigration aimed at an English audience that probably still recalled the massacre of 1622. Considerable liberty is taken with North American geography to present the continent as manageable and very English. Farrer tips his hat to the old dream of an easy passage to Asia by announcing that a ten days march will take a traveler from the Chesapeake to the Pacific. Sir Francis Drake's New Albion on the California coast emphasizes its nearness and its Englishness.

His Maiesties gracious letter to the Earle of South-Hampton, treasurer, ...

1622

-

p. 31

p. 31Indians as Slave Labor?

This illustration shows the structure where the silkworms were placed to spin their cocoons. Part of the discussion of Virginia commodities involved who would perform the labor. After the massacre of 1622, enslavement of the Native Americans seemed like a good idea to many Virginia promoters. Bonoeil also tempts his audience with the old dream of a passage to Asia.

“they that know no industry, no Arts, no culture, nor no good use of this blessed country heere, but are meere ignorance, sloth, and brutishness, and an unprofitable burthen onely of the earth: such as these … are naturally borne slaves.”

[furthermore a] “passage to the South Sea, will, beyond our falls and mountaines, through the continent of Virginia, assuredly be found.

Advertisements for the unexperienced planters of New-England, or any whe...

1631

-

p. 22

p. 22In Hindsight: Lessons Learned

Published in the year of his death, John Smith's plan for successful colony-planting in New England was drawn from his experience in Virginia. Lambasting Virginia Company officials in London, who caused needless hardship in Virginia by issuing orders based on dreams and theories rather than experience, Smith recommended a practical approach.

First, fishing, the economic base on which New England was to be founded, was far more secure than illusory searches for gold, a passage to Asia, or commitment to a nonessential product like tobacco.

Second, creating new societies and fostering initiative could best be accomplished by transferring day-to-day control of the colony to the colonists themselves.

"With such tedious letters, directions, and instructions… we did admire how it was possible such wise men could so torment themselves and us with such strange absurdities and impossibilities."

Credits

Editorial Notes: Items Pending Integration

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library