The genre fluidity of Mundus novus

Alberic[us] Vespucci[us] Laure[n]tio Petri Francisci de Medicis salutem ...

1503

-

p. 1

p. 1The Paris edition is traditionally considered to be the earliest surviving version of Vespucci’s report (1503). It was probably translated from the original Italian manuscript by Giovanni Giocondo of Verona (c. 1445 – c. 1525), the royal architect to the French king.

The publication is still clearly marketed as a letter, with Vespucci’s salutation to his friend Pierfrancesco de’ Medici on the first page serving as a title. The rest of the page is filled by the elaborate printer’s device of Felix Baligault and Jehan Lambert, a combination of separate woodblocks and typography.

Mundus nouus

1504

-

p. 10

p. 10Eucharius Silber in Rome and Johannes Otmar in Augsburg chose a different marketing strategy for Vespucci’s account. The text is still recognizable as a letter, with the salutation in a larger font and separated from the main text block.

However, the addition of a clearly distinct title – Mundus novus – powerfully shifts the text’s focus to Vespucci’s claim to have discovered a new continent. Johannes Otmar even separated the title from the text, creating a captivating half-title page.

De ora antarctica per regem Portugallie pridem inuenta

1505

-

p. 7

p. 7This 1505 Augsburg edition adds additional paratext to the letter, making it less ephemeral, more attractive, and more prestigious. This edition is the first to show New World imagery on the title page: a group of naked (dancing) Natives and a scene of five ships with men in Oriental clothing. The editor of the text, the Alsatian humanist Matthias Ringmann, added an introductory epistle and a poem relating to the newly encountered lands as preliminaries.

Ringmann also changed the title to the more learned-sounding “On the Antarctic coast recently discovered by the king of Portugal.” Based on the work of Ptolemy and Virgil, he was convinced that the lands described by Vespucci were located “almost under the Antarctic pole.”

The title did not catch on in later editions, but Ringmann’s work had the result of bringing together a group of scholars who decided to update the work of Ptolemy, resulting in the 1507 world map where the fourth continent was named America.

Von der neu gefunden Region die wol ein Welt genent mag werden, durch de...

1506

-

p. 7

p. 7The original manuscript letter (now lost) was written in Italian and subsequently translated into Latin for the first printed editions. Less than two years later, publishers in Basel, Nuremberg and Augsburg popularised the text by providing a German translation (1505). Translations in other languages soon followed: Italian (1505), Czech (1505), Dutch (1509), and French (1517).

Included in the Mundus novus letter are a number of simple scientific illustrations. One of them represents the spatial relationship of Europe vis-à-vis the new world in the shape of a triangle, whose legs mark their relative locations of the twomcontinents: “da sind wir” (we are here) and “da sind sie” (they are there). This model triangulates the geographical location of the inhabitants of Lisbon compared to those of Brazil, taking into account the shape of the world.

Van der nieuwer werelt oft landtscap nieuwelicx gheou[n]de[n] va[n]de[n]...

1507

-

p. 1

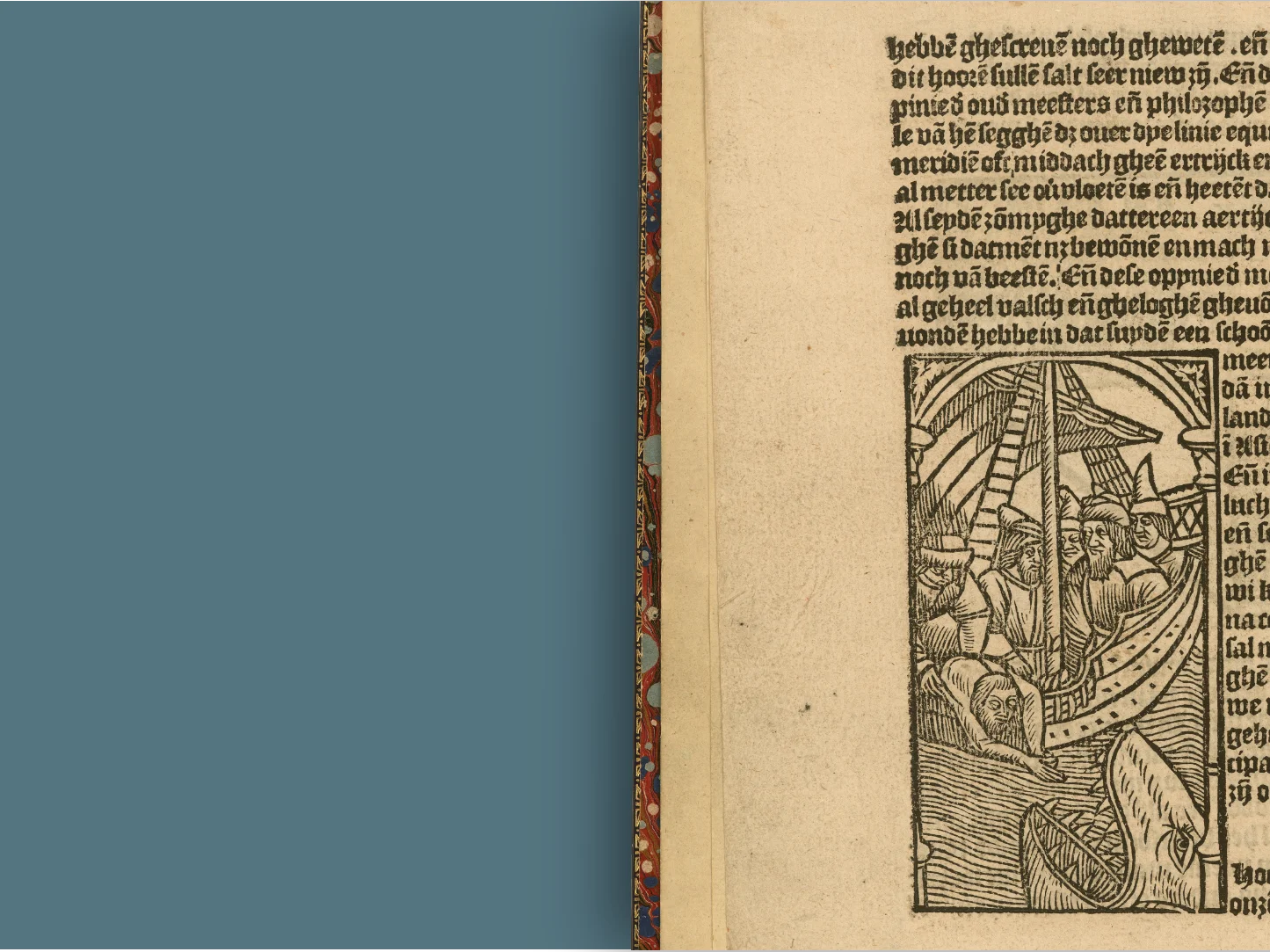

p. 1This Dutch adaptation of the letter survives in only one copy and was printed by the Antwerp publisher Jan van Doesborch, who built his success on illustrated romances and other popular genres in the vernacular. Van Doesborch seems to have judged the letter of Vespucci to be a perfect fit for his publisher’s list and transformed it into a chapbook. The story is divided into chapters and is illustrated with six woodcuts of mostly naked Natives. The print omits Vespucci’s last name, and hints that “Alberic, the best pilot in the world”, may have been an inhabitant of the Low Countries serving the Portuguese king.

Especially captivating is how Van Doesborch added another layer to the “Vespucci triangle”. The addition of illustrated scenes on the legs of the triangle changes the drawing’s original geographical meaning into a cultural one. The 90-degree angle in which the group of noble Europeans touch the naked Americans can be interpreted as symbolizing both cultural differences and encounter.

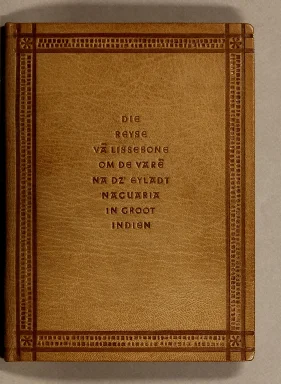

Die reyse va[n] Lissebone om te vare[n] na d[at] eyela[n]dt Naguarir in ...

1508

-

p. 7

p. 7In the Journey to Lisbon, Van Doesborch decontextualizes Vespucci even urther, to the point of transforming him into a fictional character or a generic European explorer. The publisher merges the journey of his main character, Alberic, with the German traveler Balthasar Springer’s trip to India, part of the 1505 mission of the Portuguese Francisco de Almeida. The earliest surviving printed account of Springer’s travels dates from 1509.

This rare edition puzzled a number of nineteenth-century scholars and collectors, who believed for some time that the work actually described an unknown voyage of Vespucci to the East.

The many readings of the Brevísima relación

Breuissima relacion de la destruycion de las Indias

1552

-

p. 7

p. 7At the end of his life, Las Casas returned to Europe and retired from his duties as bishop of Chiapas, spending his remaining years writing and securing his legacy. Between 1552 and 1553, he engaged some of Seville’s best printers to print his treatises.

The Brevísima relación was written ten years before as an eye-witness account in a legal case to convince the emperor to reform the 1513 Laws of Burgos: to suppress the forced labor and involuntary conversion of the indigenous people. Although his pleas were initially successful and resulted in the New Laws of 1542, they were later watered down due to violent protests by Spanish landowners.

Since Las Casas wanted a new group of American missionaries to take the treatises with them, he did not want to wait until he had the required license. This however allowed his opponents to denounce him to the Inquisition, resulting in the text being seized and banned.

Seer cort verhael vande destructie van d'Indien

1578

-

p. 9

p. 9The first re-edition and translation of the Brevísima relación (and three other treatises) happened in a completely different political setting. Since 1566, a civil war had broken out in the Low Countries between Netherlandish protestants who demanded religious freedom and Spanish governors, who increasingly responded with violence to these demands. In 1576, a mutiny amongst Spanish troops resulted in the plundering of several cities in the Low Countries, killing thousands of civilians and resulting in the open rejection of Spanish authority.

This anonymously published translation is faithful to the work of Las Casas. It keeps the original title, and adds only a one-page introduction from the translator, who avoids openly connecting the situation in the Indies to the Netherlands.

Tyrannies et cruautez des Espagnols, perpetrées Indes Occidentales, qu'...

1579

-

p. 1

p. 1One year after the Dutch translation, a French translation was made by the Flemish protestant minister Johannes van Miggrode (1531–1627). Miggrode remarks that he was about a third of the way through translating the Brevísima into Dutch when he discovered that a Dutch translation had just appeared. Consequently, he decided to avoid doing double work and produced a French version instead.

The paratext of this edition clearly aims for a different message. The title of the work is changed to Tyrannies et cruautez des Espagnols (“Tyrannies and cruelties of the Spanish”) and further down on the title page Miggrode clearly expresses that the work should be seen as a “warning to the XVII Provinces of the Low Countries.”

Narratio regionum indicarum per Hispanos quosdam deuastatarum verissima

1598

-

p. 1

p. 1The goldsmith-turned-engraver-and-publisher Theodor de Bry (1528–1598) became a Protestant in 1570 and lived in England and the Low Countries before settling in Frankfurt in 1588. His firm reached international acclaim with the production of a multi-volume, multi-lingual series of lavishly illustrated travel narratives.

In the last year of his life, De Bry published a Latin edition of Las Casas, with 17 engravings visualizing the most cruel passages from the text. Tormented, mutilated and murdered Amerindians are represented as Christian martyrs. De Bry’s version was published in the context of a war of images between Protestants and Catholics.

De Bry’s visualisation of Las Casas has to be read as a warning of the atrocities that Spaniards could inflict against Protestant nations.

Le miroir de la tyrannie espagnole perpetree aux Indes Occidentales

1620

-

p. 7

p. 7The images of De Bry’s Las Casas were very popular in Protestant Europe and were even sold without Las Casas’s text, especially in the newly established Dutch Republic. The Dutch- and French-language editions, illustrated with engravings based on De Bry, were printed nineteen times in the seventeenth century. By using the title The Mirror of the Spanish Tyranny, the editions emphasized the impact of the images and at the same time made explicit the reference to the present war between the Dutch and the Spanish.

Las obras del obispo d. Fray Bartolome de las Casas, o Casaus, obispo qu...

1646

-

p. 1

p. 1There was only one Spanish edition of Las Casas’s work in the seventeenth century, comprising five of his treatises, and including the Brevísima. The original titles were changed in three of them, adding “por los Castellanos” or “los Reyes de Castilla.” In doing this, the edition emphasized that the term Castilian had to be read in the narrow sense, and not to to be understood as Spanish.

It was printed at the request of the vicar general of the diocese of Barcelona, in the middle of the conflict between the Spanish Crown and the short lived Catalan Republic (1641-1652). The independent republic was supported by France and the conflict was part of the broader Franco-Spanish war (1635–1659). The violent repression of the revolt in several Catalan towns inspired the regional reinterpretation of Las Casas work: the Castilians, not the other Spanish regions, were responsible for the atrocities in the Indies.

The tears of the Indians

1656

-

p. 1

p. 1Las Casas’s work received - yet again - a new title in this new English translation: The Tears of the Indians. The title was possibly inspired by The Teares of Ireland (1642), a work describing the cruelties inflicted on Protestants in Ireland during the Irish Rebellion of 1641.

The translator John Phillips (1631–1706), a nephew of John Milton, dedicated the work to Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658), who had become head of state as the Lord Protector of the Commonwealth (1653). Phillips hoped that the work would inspire his countrymen to put an end to the civil war and reunite all Englishmen against their real enemy, the “Popish” Spaniards.

The cruelties of the Spaniards in the Indies were also used as a justification for English claims in the West Indies. It was the divine mission of the Lord Protector to avenge the tears of the Indians and chase the Spanish out of the Americas.

Breve relacion de la destruccion de las Indias occidentales

1822

-

p. 1

p. 1In the midst of the Latin American wars of independence, Las Casas was re-edited many times and for the first time in the Americas: Bogotá (1813), Puebla (1821), Philadelphia (1821), Guadalajara (1822), and Mexico City (1822). The editor José Servando Teresa de Mier (1765–1827) was a priest and an important supporter of Mexican independence.

In the Mexican edition’s preliminary discourse, Servando Teresa de Mier proclaimed Las Casas to be the prophet of American liberty and called for a statue of him to be erected as soon as independence was reached. From Mier’s perspective, the Creoles – that is, American-born descendants of Spanish colonists – had become the American Natives, who needed protection from Spanish colonial power.

Marketing and Formatting The History of the Americas

La istoria de las Indias. y Conquista de Mexico

1552

-

p. 9

p. 9López de Gómara’s work was published at the end of 1552 by Agustín Millán in Zaragoza (active from 1551 to 1564). The coat of arms of Charles V dominates the title page. There is almost no space for the actual title: La istoria [!] de las Indias is followed on the next line by “y conquista de Mexico.”

Published five years after the death of Cortés, there is no mention of him or the author on the title page. In an unusual introduction, López de Gómara directly addresses the readers, translators and publishers, claiming to have a privilege for ten years.

Conquista de Mexico

1553

-

p. 7

p. 7It is unclear if the edition of Guillermo de Millis – published only a couple of months later – was approved by López de Gómara. However, since the paragraph mentioning the privilege is omitted here, it seems unlikely.

Although clearly inspired by the Zaragoza edition, De Millis introduced a number of changes to make his edition more appealing. First of all, the title page was printed in two colors and in the more modern roman typeface (compared to blackletter in the 1552 edition). Secondly, De Millis tried to appeal to a Spanish rather than a Habsburg audience, by changing the coat of arms to that of Spain and by adding “Hispania victrix” in large letters at the top. Lastly, he changed the title by dividing the text in two equal parts and enlarged the title to make it more engaging.

La conquista de Mexico. 1552

1553

-

p. 5

p. 5The answer from Zaragoza to the Medina del Campo imprint was immediate. Miguel de Suelves (or Zapila), one of Zaragoza’s most prolific printers and probably a co-investor in the production of the text together with Millan, issued a new title page for the original 1552 edition, clearly aimed as an answer and warning to Millis in Medina del Campo.

He kept the Habsburg coat of arms and the blackletter typeface from 1552, but copied the longer title from Millis and introduced red ink to the title page. Finally, he emphasized that this was the authorised edition by moving the vague reference to the privilege from the introduction to the title page.

Historia de Mexico

1554

-

p. 7

p. 7Less than two years after the first edition in Zaragoza, two different 1554 editions appeared involving no less than four different Antwerp printers. On the one hand, there was the edition by Joannes Nutius, with a local privilege. On the other hand, there was the édition partagée of publishers Joannes Steelsius and Joannes Bellerus, printed by Joannes de Laet. The latter tried to surpass Nutius’s original edition by advertising (on the title page) the elaborate geographical index they had added.

La historia general de las Indias

1554

-

p. 7

p. 7A typical character of the early Antwerp re-editions of Spanish bestsellers was the smaller and more economical formats in comparison to the Spanish printers. In the case of Historia general de las Indias the Antwerp editions used 40% less paper, reducing not only material but also labor costs.

Lost in Translation: Exquemelin’s Pirates

De Americaensche zee-roovers

1678

-

p. 1

p. 1When Exquemelin sailed back from the Caribbean in 1674, he went to the Netherlands to study medicine. During his time there, he published his eyewitness account on the heyday of buccaneering, before returning to the Americas many times as both a surgeon and a buccaneer. The work is very critical of the behavior of the privateers or buccaneers, and uses the word zee-roovers (sea robbers) to describe the French and English seamen attacking the Spanish territories.

The work contains twelve engravings showing the fearless-looking leaders of the different bands, combined with scenes of violence, torture and plunder.

Eduward Meltons, Engelsch edelmans, zeldzaame en gedenkwaardige zee- en ...

1681

-

p. 1

p. 1This curious set of travel narratives was published by Exquemelin’s printer Van Hoorn under the pseudonym of Edward Melton, who supposedly travelled to Egypt, New Netherland, the West Indies and Asia. However, Melton seems to have been an invention of the publisher, who used existing travel narratives from Johann Michael Wansleben (1677), Adriaen van der Donck (1655) and Arnoldus Montanus (1671) to create the fictional journey attributed to Melton.

The account of the West Indies is in part taken from Exquemelin’s De Americaensche Zee-Roovers (1678), and allowed Van Hoorn to reuse some of the impressive plates that were made for this work.

Piratas de la America

1682

-

p. 5

p. 5In 1681, Exquemelin’s account was published in a mysterious, Spanish language edition with the fictitious imprint: Cologne, by Lorenzo Struickman. The real printer, however, was David de Castro Tartas, a Portuguese Jew from Amsterdam. Exquemelin was introduced to the community through the translator of this edition, the Sefardic Alonso de Bonne-Maison or Buena-Maison. Both men studied medicine in Leiden and shared a house in Amsterdam.

The plates in this edition are altered versions of the same plates used by Van Hoorn in 1678, so they must have been borrowed or bought for the creation of this work.

The use of the imprint Cologne, a Catholic city, made it possible to sell the work without suspicion in the Catholic world.

Bucaniers of America: or, a true account of the most remarkable assaults...

1684

-

p. 1

p. 1Exquemelin had painted an often grim and critical picture of the dealings of the French and English buccaneers. He was especially critical of Henry Morgan’s attack on Panama (1669) and accused him of stealing from his men. In the first English translation, the tone of the account changed radically: Morgan was transformed from a villain to the central hero of the story. The printer Crooke got his hands on the original Dutch plates, who were altered for a second time to create English captions.

The demand for the work called for a second edition three months later that included two additional chapters on the English buccaneers Cook and Sharp.

Histoire des avanturiers qui se sont signalez dans les Indes

1686

-

p. 7

p. 7Exquemelin returned to France in 1684 and met vice-admiral d’Éstrées whom he impressed with his stories. The vice-admiral asked his protegé Thomas de Frontignières to polish the French manuscript and the work was published in 1686 for the first time in its original language. It contained new pirate biographies (Daniel Montbars and Alexandre Bras-de-Fer), but also incorporated elaborate descriptions on natural history.

All illustrations for this edition were new and focused no longer on the fearful side of the pirates, but rather on geographical and biological descriptions. Here we find for the first time the famous image of the buccaneer in his hunting outfit, illustrations of turtle hunting at night, and the manatee, to which Exquemelin devoted a special study.

Historie der boecaniers, of vrybuyters van America

1700

-

p. 1

p. 1More than 20 years after the original publication of Exquemelin’s work, it was published again in Dutch and in Amsterdam, by the son of the original printer Van Hoorn. The 1700 edition however looks nothing like the original. It is a translation of the 1699 English edition published by Newborough.

Exquemelin’s account is only one of the stories. It also contains accounts by Basil Ringrose (1st pub. London, 1685), Raveneau de Lussan (1st pub. Paris, 1689) and Montauban (1st pub. Amsterdam, 1698). Gone is the word zee-roovers (sea robbers), gone are the scenes of destruction and cruelty, to be replaced by more heroic depictions.

Gender and the Politics of Authorship: The Case of the Peruvian Letters

Letters of a Peruvian princess

1792

-

p. 1

p. 1Despite the immediate success, the unique ending on the novel was not universally appreciated. Zilia neither chose her Peruvian lover Aza nor her European savior Déterville, and, in addition, did not accept the primacy of European values by converting to Christianity.

This resulted in a number of male rewriting or additions to the – at this point – still officially anonymous Lettres, giving them a more conventional ending. Ignace Hugary de Lamarche-Courmont published Letters of Aza, or of a Peruvian, Conclusion of the Peruvian Letters (1748). These 35 letters from the perspective of the male protagonist end with the promise of marriage, in this way creating a more traditional ending that redefined. Many later editions include the additional Letters of Aza, as if they belong to the original work.

Lettres d'une Péruvienne

1782

-

p. 3

p. 3Guiseppe Deodati de Tovazzi (born in Turin 1694) gave Italian lessons in Paris and was known for his discussions with Voltaire on the whether Italian or French was the most perfect language. His Italian translation of the Lettres (1759) appeared a year after Graffigny’s death and was published multiple times, both in Italian and in bilingual (Italian/French) editions. It aimed to be a teaching aid for those who wanted to practice Italian.

In a French language 1782 edition, Deodati is even identified as the author of the Lettres. There are however more problems with this edition, since the printer mentioned on the title page died in 1775.

Cartas de una peruana

1792

-

p. 7

p. 7Maria Romero Masegosa y Cancelada is known only for the Spanish translation and serious alteration of Graffigny’s Lettres. She added numerous moralising notes, suppressed critical passages on religion, softens the original negative judgement on the Spanish colonisation and even adds one letter at the end.

In this letter, Zilia does decide to convert to Catholicism and justifies the conquest of Peru by stressing how it improved the wellbeing of the local inhabitants.

Letters

1771

-

p. 1

p. 1After the initial success of the first edition of the novel, Graffigny’s name appeared in the privilege of the second edition (1752). But even if she was not named explicitly on the title page, reviewers identified her as the author from the very beginning.

The absence of Graffigny as the official author therefore has to been seen as an expression of expected female modesty. Only after Graffigny’s death did her name feature prominently on the title page of a good number of the editions. Since 1762, some even added a portrait and a biography.

Raynal's work(s)-in-progress

Stedman's visions of Surinam

Credits

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library