1. Saint-Domingue Before the Revolution

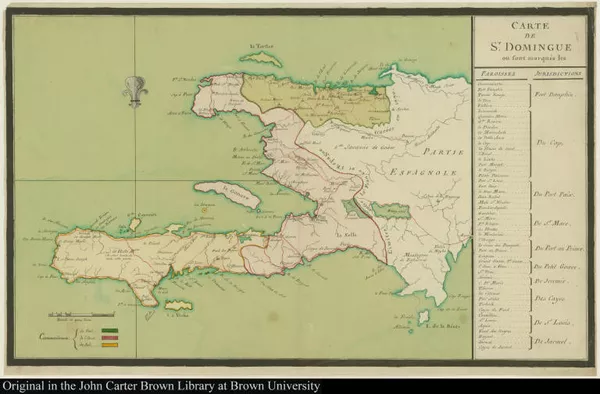

Carte de St. Domingue ou sont marqués les Paroisses Jurisdictions

1770

-

p. 1

p. 1Sugar Plantations

This 1770 map of Saint-Domingue shows the division of the colony into three administrative departments: north, west, and south. (What was called the “western” province at the time is perhaps more intuitively understood as the “central” region). At the right-hand side is a list of parishes and the ten lower-court jurisdictions into which they were grouped. The colony’s leading cities were Cap Français in the north (capital until 1750) and Port-au-Prince in the west (capital after 1750). As of 1789, the colony’s population consisted of about 30,000 white residents, a similar number of free blacks and people of color (also called “mulattoes), and roughly 465,000 (perhaps as many as 500,000) slaves of African descent. The most fortunate and powerful free people of color were prominent as coffee growers in the southern province and as military personnel in the north.

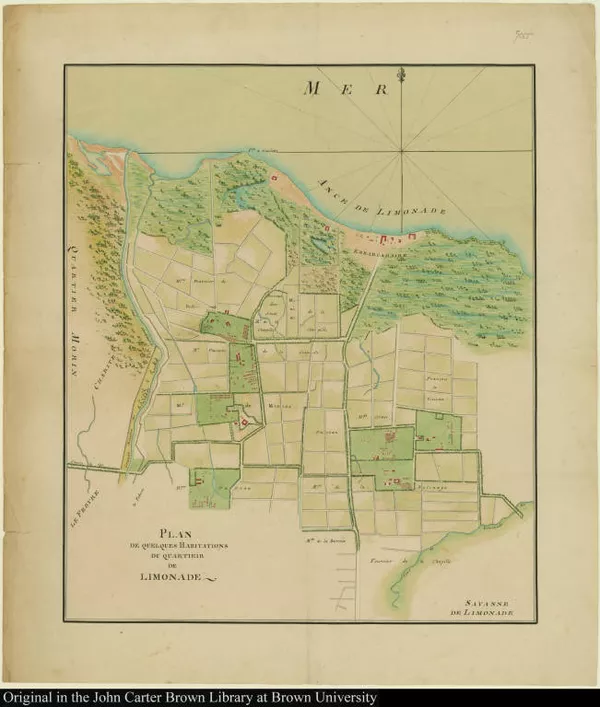

Plan de quelques Habitations du quartieir [sic] de Limonade

1785

-

p. 1

p. 1Sugar Plantations

Each of the three provinces of Saint-Domingue was divided into a set of small administrative units called parishes. The parish of Limonade was located in the northern province, to the east of the commercial capital of Cap Français. Like most of the other parishes in the northern plains, Limonade was dominated almost exclusively by sugar plantations, several of which are represented (in all their geometric precision) in this map from the mid-1780s.

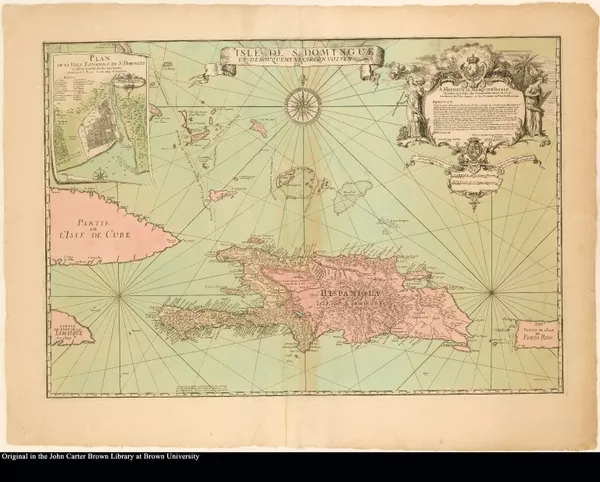

Isle de S. Domingue et débouquemens circonvoisins votre très humble et t...

1724

-

p. 1

p. 1Frézier's map

Frézier, a French military engineer and explorer, served in the colony of St. Domingue from 1719 to 1728. His map provides a wealth of topographical and navigational detail for the island and its surrounding waters. At upper left is an inset plan of the city of Santo Domingo, capital of the Spanish side of the island. Frézier dedicated his map to the Marquis d’Asfeld, director-general of French fortifications.

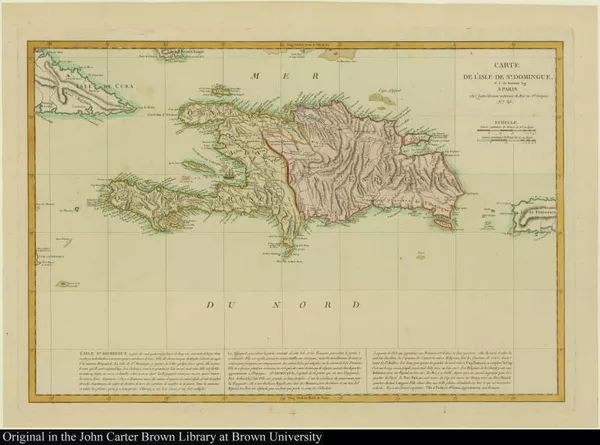

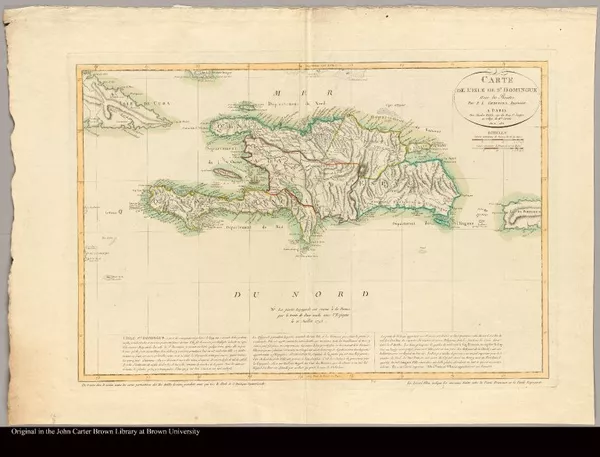

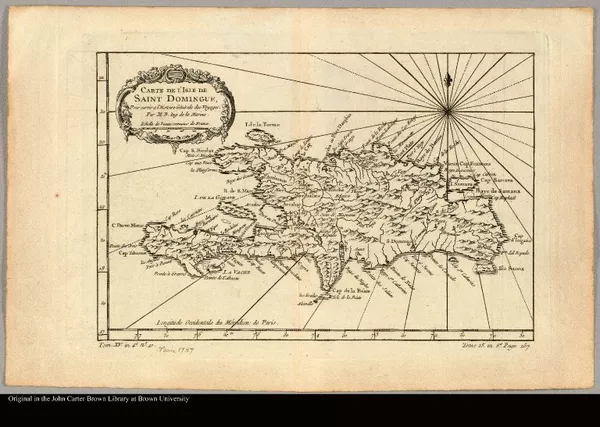

Carte de l'Isle de St. Domingue.

1760

-

p. 1

p. 1Changing boundaries

This engraved map by the Dutch cartographer P. L. de Griwtonn shows the island of Hispaniola circa 1760. At bottom is a detailed description of the French (western) and Spanish (eastern) sides of the island, a division that was formalized by the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697. The French colony of Saint-Domingue was divided into three provinces for administrative purposes: northern, western, and southern.

Carte de l'Isle de St. Domingue avec les routes par P.L. Griwtonn, Ingénieur

1801

-

p. 1

p. 1Changing boundaries

This revised state of Griwtonn’s map issued in 1801 shows the island of Hispaniola with its boundaries after Toussaint Louverture invaded Spanish Santo Domingo in1801 and divided the island into five departments. His control over the Spanish side proved to be short-lived, however. In June 1802 he was captured by an invading French army and deported to France. Leaders of the Haitian Revolution who followed Louverture continued to believe that for the island to remain independent it must be united under Haitian rule. Boundary issues were the cause of regular outbreaks of hostility between Haiti and what is now the Dominican Republic until a definitive border was agreed to by both parties in 1936.

Le code noir ou Edit du roy, servant de reglement pour le gouvernement &...

1735

-

p. 7

p. 7Code Noir (Black Code)

The Code Noir (or “Black Code”) served as the basis of the law of slavery in Saint-Domingue and the other French plantation colonies. It was promulgated by Louis XIV in 1685 at the initiative of his recently deceased chief minister, Colbert, and reflected a combination of French Caribbean legal customs and Roman law principles. Despite sanctioning a rigorously punitive scheme for the discipline of slave labor, the Code Noir legalized manumission and prohibited the torture and mutilation of slaves by other than royal authority. It also granted freed persons the same rights and privileges as those enjoyed by whites. Predictably, these protections fell afoul of the planters and their representatives.

De par le Roi. Réglement de police

1772

-

p. 7

p. 7Regulation to restore “good order”

This administrative regulation from June 1772 is typical of the concerns that motivated planters and administrators in Saint-Domingue throughout the eighteenth century, but especially in the period after the end of the Seven Years War in 1763. Stressing the need to restore “good order” and “a wise administration” after a time of “misfortune” in Port-au-Prince, the colony’s second largest city and administrative capital, the regulation prohibited slaves from bearing arms and assembling in groups. It also barred slaves from selling sugar cane, and criminalized the nighttime dances (known as Kalendas) by slaves and Free people of color.

Histoire philosophique et politique des etablissements & du commerce des...

1773

-

p. 3

p. 3Black Spartacus in the Caribbean

One of the few examples of antislavery sentiment in the pre-revolutionary French Atlantic world, the Histoire philosophique was also one of the great tracts of the Enlightenment, a mammoth multi-volume compilation of writings about European colonization whose authors included such luminaries as Diderot, Holbach, and Pechméja in addition to Raynal. In one of the Histoire’s more memorable passages, Raynal prophesied, twenty years before the event, the rise of a black Spartacus in the Caribbean – “Où est-il, ce Spartacus nouveau?” (“Where is he, this new Spartacus?”)– modeled on the great leader of a slave revolt in ancient Roman times. A perhaps apocryphal story has it that Toussaint Louverture later drew inspiration from this passage, but there is no question that it reflected widespread late colonial anxieties about the instability and viability of the plantation order.

Ordonnance du roi, concernant les procureurs & économes-gérans des hab...

1785

-

p. 3

p. 3Law prohibiting inhumane treatment of slaves

This landmark royal ordinance came at the end of decades of pragmatic concern that the “abuses introduced into the management of plantations located in Saint-Domingue” risked triggering a slave revolt of irreversible proportions. The new law prohibited the “inhumane” treatment of slaves by plantation managers and overseers, whether in the form of mutilation, the application of more than fifty lashes with a whip, or other methods likely to cause “different kinds of death.” The 1784 ordinance unleashed a torrent of criticism from the planters of Saint-Domingue, and the colony’s high courts refused to apply it until it was watered down.

The coffee planter of Saint Domingo

1798

-

p. 5

p. 5Coffee in St. Domingue

The hills that rose above the plains of Saint-Domingue provided convenient sites for the layered terraces on which coffee beans could be grown. A significant number of the colony’s coffee plantations were owned and managed by people of color. Coffee’s importance to the French colonial economy grew dramatically in the period after the Seven Years’ War (1754-63). In this book published as the British occupation of the western and southern provinces of Saint-Domingue (1793-1798) was coming to an end, a white coffee planter named P. J. Laborie offered to share his expertise for the benefit of his British counterparts in Jamaica. The plate shown here illustrates how colonial coffee growers took advantage of the mountainous terrain, unsuited for sugar cultivation, that dominated the western and southern regions.

Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de ...

1797-1798

-

p. 7

p. 7The “science” of skin color

What contemporaries called the “mixing” of races in Saint-Domingue occasioned a plethora of commentaries, nearly all white-supremacist and polemical in character, on the causes and consequences of the colony’s multiracial order. The most famous of these commentaries was by Moreau de Saint-Méry, the colonial jurist and historian whose writings on Saint-Domingue are still a major resource for contemporary scholars. In volume one of his Description, Moreau counted and categorized no less than 128 racial combinations in the colony. The “science” of skin color received one of its earliest formulations in this work, completed in 1798 after the author was exiled to the United States. It seems that Moreau was himself the father of a child by his free-colored mistress.

2. The French Revolution and the Free People of Color (1789-1791)

Vue du Cap Francois, Isle St. Domingue, prise du Chemin de l'embarcadère...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

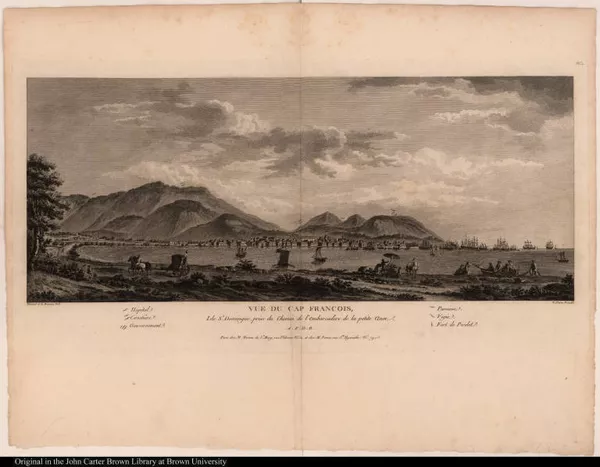

p. 1Cap Français

Throughout the eighteenth century, the city of Cap Français was the undisputed commercial and cultural capital of French Saint-Domingue. Until the colonial administrative headquarter was transferred to Port-au-Prince at mid-century, Cap Français was also the colony’s political center. The meticulously ordered geometry and highly advanced development of the city attest to its political and economic significance in the French colonial order. Cap Français was the site of one of the colony’s two high courts, or Conseils Supérieurs, which heard cases on appeals from the local tribunals and provided a central forum in which matters of administrative concern to the planter elite could be debated.

In this engraving of Cap Français, Ponce offers a panoramic view from behind the town’s prison, where captured fugitive slaves (among others) were held until they could be reclaimed by their masters.

Premier recueil de pièces intéressantes

1788

-

p. 5

p. 5No colonial representation in the French Assembly

The convocation of the Estates General in 1788 and 1789 opened the door to revolution in France. That event also had profound repercussions in St. Domingue. Like their metropolitan counterparts, the colonists (through their representatives) were eager to present their grievances to the king and nation, represented by the three estates of clergy, nobility, and all others (the “Third Estate”). In this letter to the so-called Assembly of Notables, a gathering of the first two estates only that met in the fall of 1788, the commissioners of Saint-Domingue insisted on the colony’s right to representation in the upcoming “assembly” of “the great family” that was France. However, the king’s formal convocation of the Estates in August 1788 had made no provision for colonial representatives to attend.

Motion de M. de Cocherel, député de Saint-Domingue, à la séance du s...

1790

-

p. 7

p. 7Famine vs. mercantilist policies

In the spring of 1789, as France was suffering from drought and poor grain harvests, the governor of Saint-Domingue (the Marquis du Chilleau) authorized the importation of foreign (i.e., U.S.) flour. This decision violated the mercantilist policy known as the Exclusif, which required Saint-Domingue to obtain food supplies solely from the mother country. The Exclusif had been relaxed in 1784, in recognition of the reality that the United States and Saint-Domingue had become major trading partners. But Du Chilleau’s decision was still seen as a violation of royal law, and it led to his recall by the French Naval Minister. Here the Marquis de Cocherel (1741-1826), a deputy to the French National Assembly from the western province of Saint-Domingue, defended Du Chilleau with reference to the famine “now devastating” the colony.

Cahier, contenant les plaintes, doléances & réclamations des citoyens-...

1789

-

p. 5

p. 5“All men are born free and equal”

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was approved by the National Assembly on August 26, 1789. Its Article 1 famously declared that “all men are born free and equal.” Nothing was said in the document itself about whether its terms would apply to the French colonies. The same month in which the Declaration was promulgated, representatives of the white planters and the gens de couleur of Saint-Domingue residing in Paris formed separate political clubs to advocate for their respective interests. In this pamphlet, the self-described “property-owning” free-colored representatives argued that the Declaration’s terms should apply to people of color as well as to whites. They also invoked the Code Noir provisions granting equal rights of citizenship to freed persons.

Observations sur un pamphlet

1789

-

p. 1

p. 1Free blacks criticize free people of color

The claims of the free people of color in 1789 were met not only by the predictable resistance and rejection by the white planter representatives, but also by parallel demands from the free black representatives. In another 1789 pamphlet published just before this one, the free blacks (calling themselves “American colonists”) criticized the free people of color for being of “mixed blood,” in contrast to their own supposed state of “pure blood.” Indeed, there is reason to wonder whether this rhetoric may not have been issued from the pen of an ally of the white planters in Paris. Here, an anonymous representative of the free people of color defends against the charge of racial impurity.

Convocation de l'Assemblée coloniale

1790

-

p. 5

p. 5Free people of color not welcome as equals

Early 1790 was a time of great disarray in the capital of Port-au-Prince. Royal officials were fleeing the colony, garrisons were in mutiny and riots and lynchings had erupted. Councils and assemblies were convened, adjourned, and abandoned. Some wore white cockades supporting the king. In February the white planters of the western province called for a colony-wide assembly to meet at Saint-Marc in late March. Article IX of the call made it clear that free people of color were not welcome as equals.

Just as has always been the case, Mulattos, Negroes, and other free people of color, will not be eligible to vote in the parish assemblies; but they can submit their questions to the selected deputies in each parish, and thus presenting them to the Colonial Assembly; they may, alternatively, apply to the same assembly through a single representative or patron whom they will choose from among white citizens.

Affiches américaines. Numéro 19. Feuille du Cap-Franc̦ais, du samedi 5...

1791

-

p. 5

p. 5Vincent Ogé’s rebellion

As soon as it became clear that none of the pre-existing colonial assemblies would allow free people of color to vote in the newly authorized local elections, a small and unsuccessful merchant living in Paris named Vincent Ogé (1756-1791), a free person of color, secretly returned to Saint-Domingue to organize an armed rebellion, reportedly with the aid of the British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson. Insisting that the National Assembly had implicitly authorized mulatto participation in the elections, Ogé joined forces with another free person of color named Jean-Baptiste Chavanne (1748-1791) to lead a rebellion in the northern province in October 1790. The uprising was quickly and brutally suppressed. Ogé and Chavanne were publicly executed on the wheel in Cap Français in February 1791.

Pétition nouvelle des citoyens de couleur des îsles fran̨coises, a l'A...

1791

-

p. 7

p. 7Petition for equality

The repression of Ogé’s rebellion did not end the efforts of the free people of color to assert their rights to active citizenship in Saint-Domingue. In March 1791, Julien Raimond (1744-1801), one of the leaders of the free colored community in Paris, was one of the authors of this renewed appeal to the National Assembly. The petition called upon the Assembly to enforce its own March 1790 mandate that “all persons paying taxes in the islands” were entitled to vote in the local elections. The need to qualify as taxpayers may help explain why the free people of color so often stressed their slaveholding status during this period.

Doutes proposés à l'Assemblée nationale

1790

-

p. 3

p. 3Local legislative bodies formed

The colonists did not wait for the arrival of the National Assembly’s March 1790 decree to form local legislative bodies in Saint-Domingue to deal with the new political context created by the French Revolution. They had already begun to form provincial assemblies as early as 1788 and 1789. In February 1790, the more conservative, “autonomist” planters decided to convoke a “general assembly” of Saint-Domingue in the name of the colony’s three provincial assemblies. In their “constitutional bases” of May 28, 1790, the Saint-Marc deputies (named after the town on the west coast in which they met) responded to the metropole’s authorization of local elections by insisting that only they could legislate for the colony’s internal regime, and by explicitly disqualifying non-whites from the privilege of active citizenship. In this pamphlet, one of the Saint-Marc deputies argues that the National Assembly implicitly surrendered its right to intervene in the colonies when it promulgated the Declaration of the Rights of Man.

3. The August 1791 Slave Revolt

Carte de l'Isle de Saint Domingue pour servir a l'Histoire generale des ...

1759

-

p. 1

p. 1Revolt in the North

The August 1791 slave revolt broke out in the northern plains of Saint-Domingue, in the area to the south of Cap Français. Two events are believed to have been of particular significance in triggering the revolt. The first was an August 14, 1791 meeting of slave leaders at the Lenormand plantation, in the parish of Plaine du nord, where the rebellion appears to have been planned and organized. The second was the famous voodoo ceremony on the night of August 21-22 in the forest of Bois Caïman, or “Alligator Wood,” supposedly on the mountain of Morne Rouge. There continues to be much debate among historians as to the exact nature and timing of these events.

Discours

1791

-

p. 5

p. 5Paris dictates full civil rights for free people of color

On May 15, 1791, after a highly contentious debate, the National Assembly decreed full civil rights for free people of color born to free parents, effectively enfranchising only a few hundred persons. Nonetheless, white planters regarded the measure as an intolerable intervention in the internal affairs of Saint-Domingue. On August 23, the day after the slave revolt broke out, but roughly two months before news of the uprising could have arrived in France, a planter from the northern province warned a sympathetic Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce that the decree would lead to a massacre of the white population.

Assemblée générale de la partie française de Saint-Domingue. Aux qua...

1791

-

p. 5

p. 5Paris interference = Chaos in St. Domingue

Exiled and dispersed from the colony in August 1790, the autonomist Saint-Marc Assembly was succeeded by the like-minded Second Colonial Assembly. (The Saint-Marc deputies were pardoned by the National Assembly and allowed to return to Saint-Domingue in late 1791). Both the Saint-Marc deputies and their planter-successors in the Second Colonial Assembly doubtless interpreted the news of the slave uprising as a vindication of their position that the legislature in Paris was causing chaos by interfering in the colony’s internal affairs. More immediately, as this broadside addressed by the Second Colonial Assembly to the king and National Assembly testifies, the planters were desperately focused on securing relief from the government in France.

Messieurs et chers compatriotes, nous vous adressons ci-joint des exempl...

1791

-

p. 3

p. 3North reduced to a “pile of ashes”

This remarkable letter details the devastation wrought by the August 1791 slave revolt. It was written by members of the Provincial Assembly of the North, the more moderate body of planters who opposed the autonomism of their counterparts in the Saint-Marc (and later the Second Colonial) Assembly. The northern province, they write, had been reduced to nothing more than a pile of “ashes.” “Our fertile fields are flowing with the blood of our brethren.” Over two hundred sugar plantations and the majority of the province’s coffee plantations, the letter indicates, had been entirely destroyed.

Adresse de l'Assemblée provinciale du Nord de Saint-Domingue à ses commettans

1791

-

p. 3

p. 3Royal backing for the slave revolt?

One of the earliest of efforts to explain the slave outbreak of 1791 took the form of assertions that King Louis XVI of France had emancipated the slaves. Indeed, the connection between royalism and insurrection would grow so strong that for much of the revolution the slaves were forced to rebut charges that they were counter-revolutionary allies of the king, the Capetian “tyrant.” In the immediate aftermath of the August 1791 revolt, however, the planters were concerned above all to refute the suggestion that the slaves’ actions had royal backing. Condemning these rumors as the work of “true enemies” of Saint-Domingue, the Provincial Assembly of the North called upon the planters to unite or face “total ruin.”

Gazette de Saint-Domingue

1791

-

p. 5

p. 5Emancipation as reward

The Gazette de Saint-Domingue began publication during the revolutionary years. The first reference to the August 21-22 slave revolt and its unfolding did not appear until September 3, suggesting an editorial agenda to minimize, if not deny altogether, the reality of the northern planters’ loss of control over their slaves. This report recounts the Colonial Assembly’s decision to emancipate a plantation slave driver named Jean, in exchange for his help in capturing Jean-Baptiste Cap, one of the leaders of the August 1791 revolt. Emphasizing that it was important “in the present circumstances to present this example as a model” to the colony’s slaves, the Colonial Assembly ordered the issuance of a silver medal in the driver’s name. Jean-Baptiste Cap, the elected “king” of Limbé and Port-Margot parishes, had been captured while trying to recruit slaves on a plantation and was broken on the wheel.

Sur les troubles de Saint-Domingue

1791

-

p. 7

p. 7Equality between free people of color and whites deemed essential

It was not surprising that a white planter community threatened by the events of August 1791 would turn to the free people of color for help, for they had traditionally played a significant role in leading and serving in the colonial militias that chased down fugitive slaves in the mountains of Saint-Domingue. This service lent the free people of color a strategic importance that was recognized in October 1791 by a white planter named Milscent, himself a leader of a fugitive slave militia. Milscent intervened to inform the public that his experience in containing slave resistance is “necessarily linked to the facts that trouble the colony at this moment.” For Milscent, the equality of free people of color with whites was essential to the very preservation of slavery in Saint-Domingue.

4. The Civil Commissions, The Free People of Color, and Abolition (1791-1793)

Proclamation des Commissaires nationaux-civils

1791

-

p. 5

p. 5First civil commission to restore order

In November 1791, the first of what would become three separate civil commissions dispatched by French metropolitan assemblies to manage the chaos of colonial events arrived in Cap Français. The first commission, consisting of Philippe Rose Roume de Saint-Laurent, Frédéric Ignace de Mirbeck, and Edmond de Saint-Léger, was charged with restoring order in Saint-Domingue and enforcing the decrees of the National Assembly, including the controversial May 1791 decree that granted full political rights to a limited segment of the free people of color. The commissioners had been initially appointed in July, before the slave revolt broke out; their arrival in the colony under radically changed circumstances only strengthened the pre-existing planter suspicion of metropolitan interference.

Opinion

1792

-

p. 5

p. 5End the oppression of free people of color in St. Domingue!

For a brief but critical period after late August 1791 the white planters of Saint-Domingue and their allies in France seemed to forget all about what they had earlier insisted was the necessity of maintaining a strict regime of racial discrimination against the free people of color. Marguerite-Elie Guadet, a deputy from the Gironde, entered the debate in the National Assembly to argue that the oppression of free people of color must end in Saint-Domingue. Only by doing so, he observed, would whites be able to secure the cooperation of the free people of color in suppressing the slave revolt.

Réflexions politiques sur les troubles et la situation de la partie fra...

1792

-

p. 5

p. 5Whites and free people of color partner to keep slaves on the plantations

In April 1792, the Legislative Assembly (the successor to the National, or Constituent, Assembly in France) ended all racial discrimination against free people of color in the colonies. The decision vindicated those who believed that the Declaration of the Rights of Man ought to extend across racial lines, but also gave the free people of color a reason to ally themselves more fully with the white planters at a time of great mutual insecurity. In this June 1792 pamphlet, Juste Chanlatte (1766-1828) and several other prominent free people of color from Saint-Marc argued that only a “constitutional union between whites and people of color” could return the slaves to the plantations. Violent conflict between whites and free people of color continued as before, but the 1791 revolt also greatly intensified the hostility between free persons of color and the slaves.

Proclamation

1792

-

p. 3

p. 3Second civil commission to restore order

A second civil commission was dispatched to the colony in June 1792, with the ongoing task of “restoring order” to Saint-Domingue, but also to enforce the April law granting full political rights to the free people of color. Léger- Félicité Sonthonax, Etienne Polverel, and Jean Antoine Ailhaud arrived with 6,000 soldiers in Saint-Domingue in late September, only a week after the monarchy was abolished and the first French republic was declared. Their momentous tenure in Saint-Domingue, which lasted until the summer of 1794, witnessed the overlapping radicalization of both the French and Haitian revolutions. In this pamphlet, they made clear their determination that henceforth only two classes of people would exist in the colony: slave and free.

Prospectus pour le rétablissement des Affiches americaines

1792

-

p. 3

p. 3French Revolution opens a “Pandora’s box” in St. Domingue

This short-lived effort to resume publication of the Affiches americaines in Cap Français, after it had been disrupted by the August 1791 slave revolt, revealed volumes about the anxieties of white planters towards the middle and end of 1792. The prospectus argued that the Revolution, while liberating the oppressed in France, had opened a “Pandora’s box” in the colonies. Among the causes of the colony’s distress, the author singled out the explosion of printed material (pamphlets and newspapers) since the beginning of the Revolution. But it was the characterization of the newspaper’s hoped-for audience – both whites and free people of color, united by a “common interest” – that most neatly illustrated the changing nature of colonial politics in the new Saint-Domingue.

Mémoire pour les citoyens Verneuil, Baillio jeune, Fournier et Gervais,...

1793

-

p. 7

p. 7Role of the petits blancs (poor whites)

Far less is known about the role of the petits blancs (or poor whites) in the early phases of the Revolution than about the planter and mulatto elites. They seem to have played an important role in the emergence of “patriot” Jacobin clubs in Saint-Domingue though membership in such groups at other levels of society was driven at least as much by the changing political climate in France as by local political conviction. In this pamphlet, a petit blanc, Baillio, and his associates condemned Sonthonax for sponsoring a race war in Saint-Domingue and failing to enforce the April 4 decree. Baillio’s charges were entirely hypocritical; he and other petits blancs had been deported by Sonthonax for encouraging a December 2, 1792 race riot in Cap Français.

Proclamation. Au nom de la République

1793

-

p. 3

p. 3Sonthonax proclaims emancipation

Sonthonax’s decision on August 29, 1793, to free the slaves of the northern province of Saint-Domingue is one of the most famous and also most ambiguous moments of the Haitian Revolution. Announcing that a “new order of things will be born” and that the “old servitude will disappear,” the emancipation is often seen as one of the great humanitarian vindications of revolutionary ideology. A onetime lawyer and a committed Jacobin, Sonthonax was also an ambitious revolutionary politician determined to make his mark on the course of events. His proclamation came at a time when a dramatic augmentation of French forces was desperately needed to counter the combined Spanish and British military threats.

Proclamation

1793

-

p. 3

p. 3Emancipation proclamation in Kreyòl and French

Commissioners Polverel and Sonthonax fulfill the promise in their emancipation proclamation of June 21, freeing those slaves who came to the defense of the French Republic during the traitorous uprising led by Governor Galbaud. Article XI spells out the process by which rebel slaves could secure their freedom in return for future military service. The commissioners devote most of the proclamation to outlawing French military officers, whom they accuse of counter-revolution and support for a Spanish takeover of the colony.

Proclamation

1793

-

p. 3

p. 3This copy is one of the few published documents of that period written in Kreyòl, the lingua franca of Haiti.

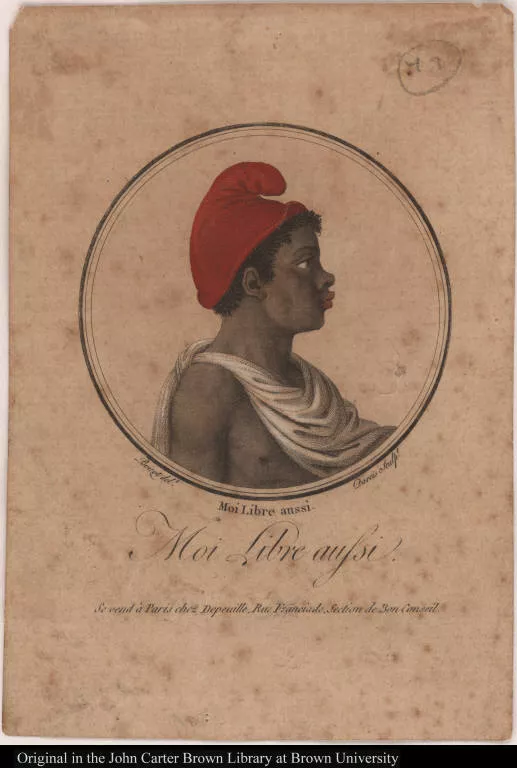

Moi Libre aussi.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Me free, too!

The widespread depiction shown on this medallion reveals that even sympathy for the cause of racial equality could come shrouded in condescension and a subtle form of racism. The “me free too” ideology reflected here essentially denied that free people of color (not to mention slaves) could think and act out of their own sense of political and social interests and goals.

5. War and Occupation (1793-1798)

Courrier politique de la France et de ses colonies

1793

-

p. 1

p. 1British occupation

In September 1793 British forces arriving from Jamaica began a five-year occupation of parts of the western and southern provinces of Saint-Domingue. Sonthonax and his fellow civil commissioners thus found themselves managing a three-way territorial war against both Britain and Spain. In the western and southern provinces this war partly took the form of efforts to secure the allegiance of the free people of color. In this exchange of letters, John Ford, the commander of the British squadron, warned Sonthonax of an impending invasion of Port-au-Prince and promised to safeguard the interests of the free people of color. Sonthonax replied that the city’s white residents were sworn to “remain French or die,” and that they would never again allow their “brothers of color” to suffer the “yoke of barbarous prejudices.”

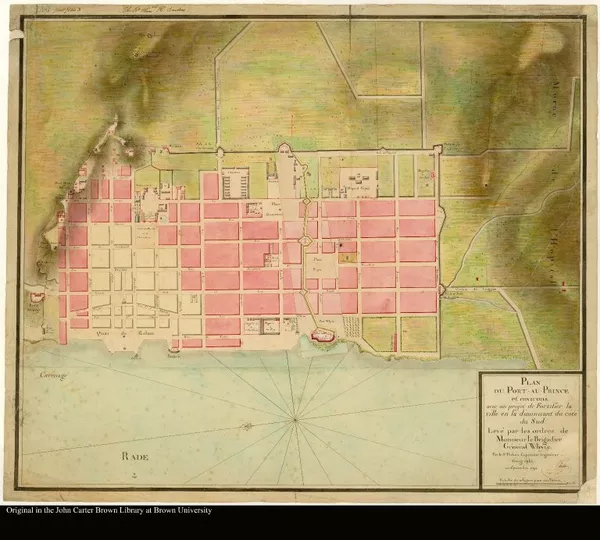

Plan du Port-au-Prince et environs avec un projet de Fortifier la ville ...

1794

-

p. 1

p. 1Port-au-Prince under occupation

Port-au-Prince became the administrative capital of Saint-Domingue in 1750. Like Cap Français, it was the site of one of the colony’s two high courts, or Conseils Supérieurs. In September 1793, British forces arriving from Jamaica began a five-year occupation of parts of the southern and western provinces. The British started by occupying the southern port of Jérémie and would eventually take Port-au-Prince itself in June 1794.

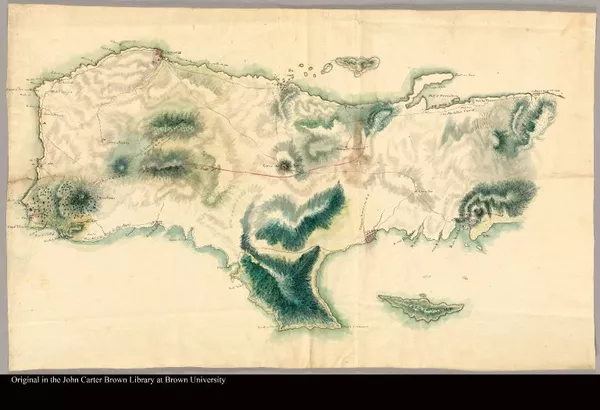

[Haiti, southwestern peninsula, between 1793 and 1798]

1793

-

p. 1

p. 1British invasion, 1793-1798

Military plan. The “British frontier line,” marked in red, refers to the invasion under Brig. Gen. Richard Whyte, 1793-1798.

Sonthonax, ci devant commissaire civil, délégué a Saint-Domingue, a l...

-

p. 3

p. 3Campaign to impeach Sonthonax and Polverel

In the aftermath of slave emancipation and British invasion in late 1793, a group of planter representatives began an unyielding campaign before the National Convention to impeach Sonthonax and Polverel as “counter-revolutionaries” responsible for the “disasters” of Saint-Domingue. The National Convention succeeded to the Legislative Assembly following the overthrow of the French monarchy in August 1792. In addition to Page and Brulley, the group included Jean-Baptiste Millet (a planter from Jérémie) and the lawyer-planter Larchevêque-Thibaud, deported from the northern province by Sonthonax. In June 1793 Sonthonax and his fellow commissioners left Saint-Domingue for Paris to defend themselves. Sonthonax insisted here that the colony would have succumbed entirely to foreign invasion without his decision to free the slaves, which created 200,000 new soldiers “in a single day” for the Republic.

Débats entre les accusateurs et les accusés, dans l'affaire des colonies

1795

-

p. 5

p. 5Sonthonax and Polverel on trial

After a series of delays, the trial of Sonthonax and Polverel proceeded under the auspices of the National Convention’s colonial commission, chaired by an antislavery Parisian lawyer named Jean Philippe Garran de Coulon. Known as “the affair of the colonies,” the debates between the planter representatives and the civil commissioners lasted from January to August 1795, and resulted in an acquittal for Sonthonax (Polverel died midway through the trial). The civil commissioners argued that Saint-Domingue had already been in the midst of upheaval before they arrived, due to the brutally repressive tactics of Brulley and company in responding to the unrest in the northern province.

Extrait d'une lettre du commissaire Sonthonax, au general Bauvais

1797

-

p. 3

p. 3Slave revolution vs. mulatto consolidation

One of the chief axes of division within Saint-Domingue throughout the 1790s was that between the slave revolution in the north, led by Toussaint Louverture, and the mulatto effort to consolidate power in the south, led by André Rigaud (1761-1811). Rigaud was a former member of the French contingent that had served in the American revolutionary war. In this letter written from Les Cayes, Rigaud denied allegations that he was entering into negotiations with the British to surrender Léogane, and promised to put up a fight for the southern province. In 1799, Louverture’s and Rigaud’s forces began fighting the War of the South, which would end in victory for Louverture in August 1800.

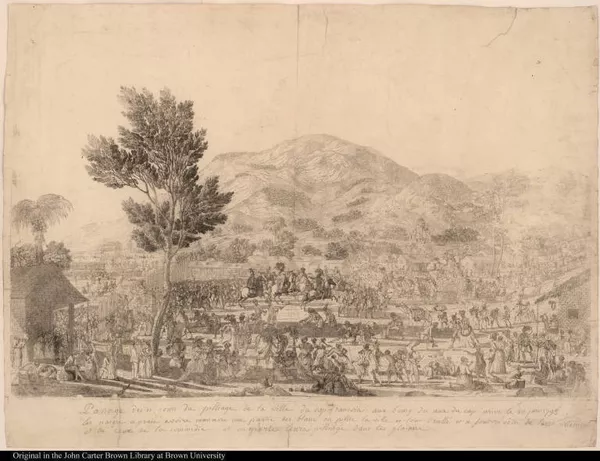

Passage des 11 jours du pillage de la ville du Cap Français...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1The pillage of Haut du Cap

This print shows the pillage of present-day Haut du Cap (here identified as Cap Français) by the insurgents who took the town from republican troops during June 19, 20, and 21, 1793. It’s a scene of warfare, celebration, looting, and drunkenness. Blacks, dressed in costumes from the Cap Français theater, celebrate their victory and mock whites. An inscription on this unfinished proof states that during the eleven days of pillage blacks massacred whites and burned the town. The painter of the work from which this engraving was made is probably J. L. Boquet, a marine painter living in Saint Domingue, who returned to France in 1793. He painted two paintings, now lost, on his return to France. This proof copy appears to be a part of that series.

Relation de l'anniversaire de la fèdération [!] du 14 juillet 1789

1795

-

p. 1

p. 1St. Domingue émigrés celebrate Bastille Day in Charleston

The flow of white and free colored émigrés from Saint-Domingue began with the August 1791 slave revolt and continued in fits and starts until the end of the Haitian Revolution in 1804. Some of these planters brought domestic and other slaves with them to North American port towns such as Charleston, New Orleans, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. This newspaper article recounts the émigré celebration of Bastille Day in Charleston on July 14, 1795. The émigré communities were at pains to advertise their loyalty to the French republican cause and defend themselves from charges of counter-revolutionary treason.

Du gouvernement de Saint-Domingue, de Laveaux, de Villatte, des agens du...

1797

-

p. 7

p. 7St. Domingue’s ills blamed on Sonthonax

This diatribe against two of the key military figures in Saint-Domingue as of 1795 and 1796 was yet another attempt to explain the breakdown of order in the colony by blaming it on persons connected to Sonthonax. Named interim governor of the colony by Sonthonax back in October 1793, Etienne Maynard Bizefrance de Laveaux (a white officer) rose to the top of the military hierarchy to become a division general by 1795. Jean-Louis Villatte was a mulatto who had been given an important military commission by Sonthonax in 1793 and later led a movement against Laveaux. In the passage shown here Laveaux was singled out for destroying the peace of Saint-Domingue.

Discours

1797

-

p. 5

p. 5View from the metropole - Use force to pacify St. Domingue

The restoration of “order” and French sovereignty in Saint-Domingue remained a priority for both the metropolitan government and the planters throughout the years of British occupation and Toussaint Louverture’s consolidation of leadership over the slave revolution. In this address to the Council of 500 (the lower house of the French legislature during the period of the Directory), a former military officer and then-deputy named Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse (1748-1812) advocated the use of force to pacify the “Vendée” of Saint-Domingue. He meant to compare the slave revolution to the royalist, pro-clergy peasant uprising in the west of France in late 1793 that was brutally repressed by the French revolutionary armies, at the cost of tens of thousands of lives. Villaret de Joyeuse would later serve under General Leclerc as commander of the French fleet that invaded Saint-Domingue in 1802.

Rapport sur les troubles de Saint-Domingue

1797-1799

-

p. 7

p. 7Contemporary history of the Haitian Revolution

Not all metropolitan voices in 1797 were raised in favor of a counter-revolutionary restoration of slavery in Saint-Domingue. Garran de Coulon closed his chairmanship of the commission assigned to investigate the causes of the slave revolution with this report “on the troubles of Saint-Domingue.” Technically a summary of the trial of Sonthonax and Polverel before the National Convention, the report remains one of the most important contemporaneous histories of the Haitian Revolution. In his introduction Garran de Coulon warned that any attempt to return the Haitians to slavery would result in the irreversible loss of Saint-Domingue and the massacre of the colony’s remaining white population.

6. Toussaint Louverture

Histoire de Toussaint-Louverture chef des noirs insurgés de Saint-Domingue

1802

-

p. 8

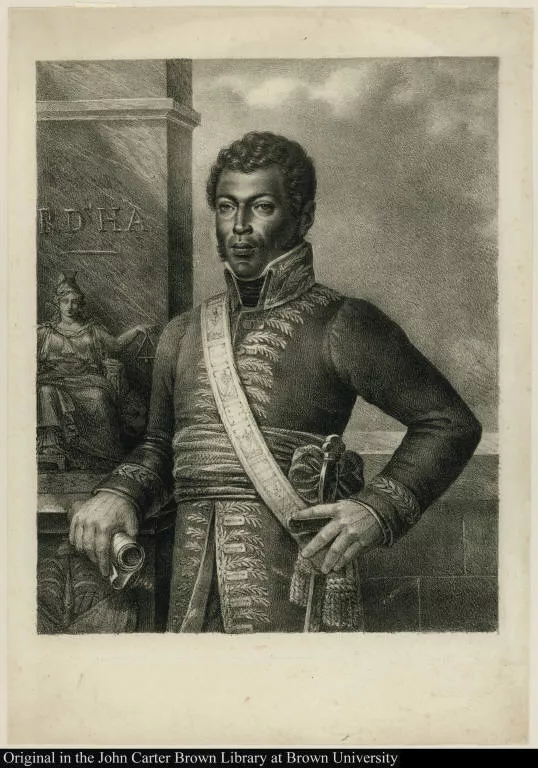

p. 8First published portrait of Louverture

This is the first published portrait of Toussaint Louverture. Although printed during his lifetime, it was probably not drawn from life. Arguably the most formidable and fascinating figure in the story of the Haitian Revolution, the man who called himself Toussaint Louverture (“the Opening”) was a free man before 1789, the coachman and manager on the Breda plantation near Cap Français. He was about fifty at the outbreak of the slave insurrection in 1791. As lieutenant to the insurgent generals Biassou and Jean-François, he wore the uniform of Spain. A devout Catholic, Toussaint distrusted the anti-religious and anti-royalist French revolutionaries. Even after the proclamation of general emancipation in October, 1793, Toussaint led anti-French troops besieging Le Cap. Finally, in May, 1794, because of the Convention’s abolition decree, Toussaint switched sides. Over the next seven years Toussaint united the entire island under his command, worked to revive the plantation economy, and proclaimed an autonomous constitution for Saint-Domingue with himself as governor for life. It was then that Napoleon took notice.

Toussaint Louverture Chef des Noirs Insurgés de Saint Domingue.

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Louverture at the height of his power

This equestrian engraving of Toussaint Louverture, “leader of the insurgent blacks of Saint-Domingue,” was intended to capture a moment when the black general was at the height of his power. In 1800, Louverture had defeated the mulatto forces led by Rigaud in the southern department, thereby giving the black general control over all of the territory of French Saint-Domingue. The following year, 1801, saw Louverture extend his sovereignty over the island’s eastern (or Spanish) side as well. This success proved to be short-lived. Louverture was captured and deported to France in 1802, where he died a prisoner of Napoleon in an Alpine prison near the Swiss border.

Discours prononcé par C. Lavaux, député de Saint-Domingue, le troisie...

1797

-

p. 7

p. 7General Laveaux defends Louverture

Among Louverture’s more crucial supporters in the French military hierarchy in Saint-Domingue was the former governor and French army division general Laveaux, who appointed Louverture his lieutenant in April 1796. After Sonthonax returned to Saint-Domingue in May to commence his second mission, Louverture was elevated to the rank of division general. His authority rendered obsolete, Laveaux returned to France as a deputy of Saint-Domingue to the Council of the Ancients, the upper house of the French legislature, where he defended his former protégé from critics. Citing Louverture’s decision to spare the lives of 200 French émigré prisoners, Laveaux declared that he “must show you the generosity of a black who was [once] a slave.”

Arrêtés des différentes communes de la colonie de St.-Domingue, adres...

-

p. 3

p. 3Former slaves support Louverture

In January 1798 the Directory replaced Sonthonax with a former member of the military command that had handled the repression of the 1793 Vendée uprising in western France, General Gabriel Marie Théodore Joseph d’Hédouville. The ex-slaves instantly suspected Hédouville of wanting to return them to the plantations. Groups of former slaves around the colony drew up petitions asking Louverture to assume full control. A petition from the parish of Petite-Rivière, in the western province, is a rare example of a Haitian Creole document from this period. The former slaves declared their refusal to work until Moïse, one of Louverture’s military subordinates who led his men in an uprising against French authority, was released from prison.

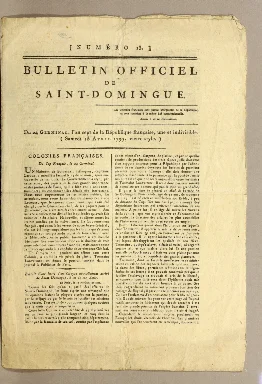

Numéro 13. Bulletin officiel de Saint-Domingue. Du 24 germinal, l'an se...

1799

-

p. 1

p. 1Louverture inspired by Declaration of the Rights of Man

In August 1797 Louverture more or less forced Sonthonax out of the colony, leaving the black leader as the highest ranking official in Saint Domingue, general in chief of the French army. Stories about Louverture’s origins, his rise to prominence, and his ambitions for the future of Saint-Domingue circulated far and wide, in both the Caribbean and in France. In this January 1799 letter, an anonymous writer related the perhaps apocryphal story of Louverture reading the Abbé Raynal’s Histoire philosophiques et politiques des deux indes before the Revolution and taking inspiration from its foreshadowing of a Black Spartacus in the Caribbean. But it was the Declaration of the Rights of Man in 1789, we are told, that gave Louverture the actual idea for the role he would take.

A memoir of transactions that took place in St. Domingo, in the spring of 1799

1802

-

p. 3

p. 3British visitor sees equality in Haiti

This memoir by a British military officer who accidentally found his way to Saint-Domingue near the height of Louverture’s power provides a revealing glimpse of how foreign observers perceived the black general and Haiti. The American hotel in Cap Français where Rainsford stayed presented a “perfect system of equality,” with blacks and whites of different social ranks dining and conversing naturally with each other. When Louverture dropped in unexpectedly for dinner, Rainsford reports, he declined to take the head of the table.

7. The War of Independence (1802-1803) and the Struggle for Recognition

La vie de Toussaint-Louverture, chef des noirs insurgés de Saint-Domingue

1802

-

p. 10

p. 10Campaign to vilify Louverture

The campaign to vilify Louverture acquired even greater ideological stakes with the impending invasion of Saint-Domingue under the orders of Napoleon Bonaparte in early 1802. According to an 1814 History of Toussaint Louverture by M. D. Stephens, published in London, Bonaparte’s regime hired a writer named Jean-Louis Dubroca (1757-1835) to lead the propaganda war against Louverture. Dubroca’s 1802 book (translated into English the same year) castigated the black general for what it described as his “profound hypocrisy and desperate ambitions.” In 1805 Dubroca published a similar diatribe against Dessalines that appeared in Spanish and German versions.

Recensement

1804

-

p. 3

p. 3End to slavery, but not forced labor

The revolution ended slavery in Saint-Domingue but not forced labor. Louverture and several of the early governments of independent Haiti used the army to impose forced work on the plantations, a decision not made any easier by the threat of international embargo and the prospect of famine. This intriguing plantation census form from 1804, the first year of Haitian independence, shows various head counts for whites, free people of color, and free domestic servants, but none for slaves. On the reverse side, however, several hundred (possibly several thousand, the writing is unclear) “slaves” are listed as being subject to the head tax.

Essai sur nos colonies, et sur le retablissement de Saint Domingue

1805

-

p. 9

p. 9Continued threat of French invasion

Starting in October 1802, four months after Louverture was effectively kidnapped and deported to France, the Leclerc expedition was beaten back by the combined forces of Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Alexandre Pétion. For more than two decades after Haitian independence was declared on January 1, 1804, however, the threat of another French invasion hung constantly over the new state. In this 1805 pamphlet, an exiled planter named Jean Abeille argued that “negotiations alone” would not bring Saint-Domingue back under French control. He called for the use of force if necessary to restore the French empire’s most valuable possession.

Faits historiques sur St.-Domingue, depuis 1786 jusqu'en 1805

1814

-

p. 7

p. 7French plan to re-conquer Haiti

That Haitian fears of another French invasion were not illusory is demonstrated by this 1814 pamphlet suggesting a plan for the re-conquest and resettlement of Saint-Domingue. In a companion volume published the year before, the author invoked the success of the British in suppressing slave resistance in both Saint-Domingue and Jamaica as a model for the French to follow. The present volume opened with an epigraph rehearsing the curse of Ham, the biblical passage traditionally used in the early modern period to justify black slavery. The Haitian Revolution led to a resurgence of anti-black racism throughout the early nineteenth-century Atlantic world.

Pieces officielles relatives aux négociations du gouvernement français...

1824

-

p. 7

p. 7France negotiates with the Haitian government

France finally recognized Haitian independence in 1825, in exchange for Haiti’s payment of a debilitating indemnity of 150 million francs. France claimed the indemnity on behalf of former colonists who had lost their plantations and fortunes during the revolution. In this document, published one year prior to the final agreement, the Haitian state expressed its frustration with the fickle and imperious negotiating stances of the French government, which varied from a claim of “abolute sovereignty” over Haiti in 1814, to indemnity in 1822, to “external sovereignty” in 1824.

8. Impact and Representation of the Revolution

A dissertation on slavery

1796

-

p. 1

p. 1Impact of the Haitian Revolution in the U. S.

The news of the Haitian Revolution echoed throughout the slave societies of the Atlantic world. The immediate effects of the Revolution were felt most strongly in the Caribbean, but its ideological impact was perhaps greatest in the United States, where thousands of French planters went to take refuge. In this 1796 treatise advocating the gradual abolition of slavery in America, a leading Virginian jurist and anti-federalist named St. George Tucker wrote that the Haitian experience was “enough to make one shudder” in fear of “similar calamities in this country.” He recommended colonization in unsettled western territory rather than full political equality and coexistence with whites.

An historical account of the black empire of Hayti

1805

-

p. 12

p. 12Sympathetic account of the Haitian Revolution

One of the few fully sympathetic accounts of the Haitian Revolution by outsiders was written by the British military officer Marcus Rainsford. Rainsford’s volume opened with several graphic engravings by J. Barlow illustrating the brutal methods used by French invading forces to repress the Haitian armies in 1802 and 1803, as well as the violent retribution exacted by Louverture’s and Dessalines’s men. This engraving dramatized the use of bloodhounds that General Rochambeau is said to have brought from Cuba to aid in the “extermination” of the black forces.

Le conseil d'état, au peuple et à l'armee de terre et de mer de Hayti

1811

-

p. 7

p. 7Hereditary monarchy for Haiti?

A series of former generals in Toussaint Louverture’s army succeeded to the leadership of Haiti after independence in 1804. Within a few years of independence, Haiti was effectively split into two halves: a northern monarchy led by former black slaves, and a republic led by elite free people of color in the south. One of Louverture’s former officers, Henri Christophe, proclaimed himself president of (northern) Haiti in 1807. In 1811, he convened his council of state to revise the 1807 Constitution with the goal of instituting a hereditary monarchy and nobility in Haiti. Denouncing the “horrible convulsions” and “factions” that had come before, Christophe’s government insisted that a single, hereditary ruler was necessary to bring stability to Haiti. The pamphlet notes that even though Haitians are, like the Americans, “a new people,” the institution of the American presidency was unsuited to the Old World origins of Haitian society.

[Alexandre Sabés Pétion]

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Alexandre Pétion

Alexandre Pétion (1770-1818) was the first president of the (southern) Republic of Haiti upon its establishment in 1807. He served in this office until 1816, when a new constitution made him President for life. Pétion had risen to prominence as an officer in the French army under the French emissary Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, fighting against British forces in Saint-Domingue. He sided with the mulatto uprising in the south against Toussaint Louverture and left the island for France in 1800 upon Louverture’s victory. He returned as a French army officer with the Leclerc expedition in 1802, then switched sides when it became clear that Dessalines and the black army would prevail. Pétion was one of the signatories of the act of Haitian independence in January 1804.

Manuscrit d'un voyage de France a Saint Domingue , à la Havanne et aux U...

1816

-

p. 3

p. 3Eyewitness to the Revolution

The anonymous author of this manuscript eyewitness account of the Haitian Revolution claims to have been present continuously in Saint-Domingue from the revolution’s beginnings in 1789 to its end in 1804, a feat that not many white residents of the colony can claim to have matched. His parents dispatched the author to Saint-Domingue after he refused to obey their wish that he become a Capuchin friar. In Part II of his manuscript, dated 1816, the author writes that the “troubles began in this unfortunate colony towards the end of September 1789” with the importation of the French revolutionary symbol, the “cursed” red-white-and-blue cockade.

Credits

Editorial Notes: Items Pending Integration

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library