1. Sloane in Context: Assembling the Natural History of Jamaica

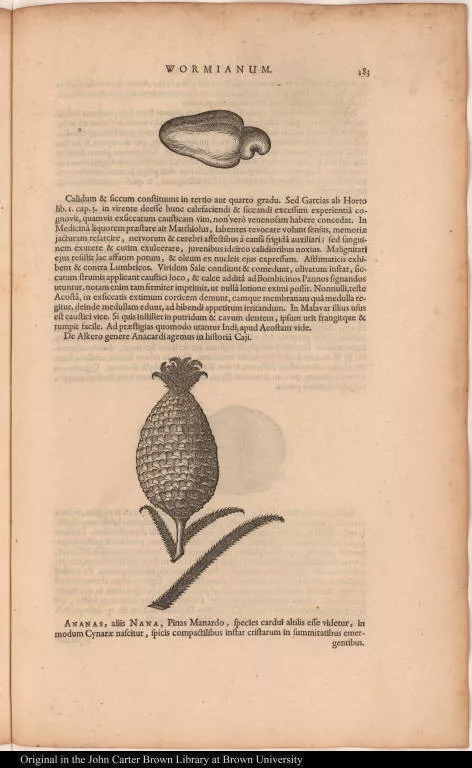

[Cashew apple and pineapple]

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Cabinets of Curiosity

Worm was a Danish physician and antiquary. His famous frontispiece (evidently an accurate view of his collections) is emblematic of the early modern cabinet of curiosities. Renaissance traditions of collecting the rare and marvelous, featuring striking juxtapositions rather than strict classificatory order, continued to influence seventeenth-century collectors. Like Worm, Sloane was a physician, an identity reflected in the large number of natural specimens in his collection. Worm’s image vividly captures the range of objects that enticed the curious, from natural specimens to artificial curiosities. Exotic objects were especially prized by such collectors, who envisioned their work as the gathering of new and useful particulars and the pious re-assembly of God’s universe in microcosm.

Jamaica viewed

1661

-

p. 1

p. 1Surveying Jamaica

Hickeringill was a church minister who fought against Charles I in the English Civil Wars, before spending time in Jamaica. A Spanish colony since Columbus first made landfall there in 1494, Jamaica’s early economy revolved around ranching and exporting hides. The Spanish introduced Africans, many as ranchers, as the indigenous Taino population was decimated by the diseases they brought. In 1655, although it failed to capture Hispaniola, Oliver Cromwell’s ‘Western Design’ for supplanting Spanish power in the Caribbean did succeed in taking Jamaica. There was little sign that the island would become among the most lucrative American colonies, as sugar-planting had not yet been established. Hickeringill’s text is one of several early English surveys—often rather defensive—of the island’s potential value. Sloane owned a copy.

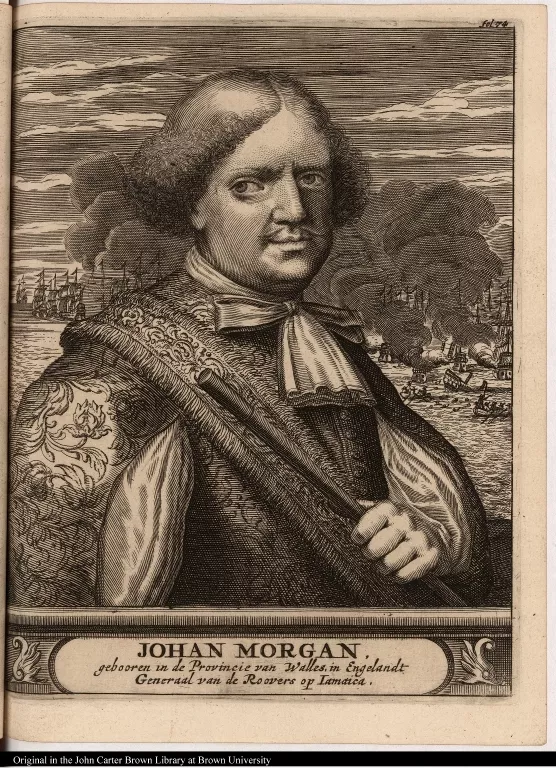

Johan Morgan gebooren in de Provincie van Walles in Engelandt Generaal v...

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1From Piracy to Plantation

Captain Henry Morgan’s career epitomizes the intense military rivalry among Europeans in the Caribbean. A state-sponsored privateer, enjoying the Crown’s license to harass foreign and especially Spanish shipping and settlements, Morgan executed numerous raids, the most celebrated being his sack of Panama in 1671, despite England then being formally at peace with Spain. Instead of being punished, he was made lieutenant-governor of Jamaica. When Sloane came to Jamaica in 1687, the aging Morgan became one of his elite clients, although he also engaged the services of African healers on the island. His death in 1688 symbolizes the transition in the political economy of Jamaica from privateering to plantation-based agriculture.

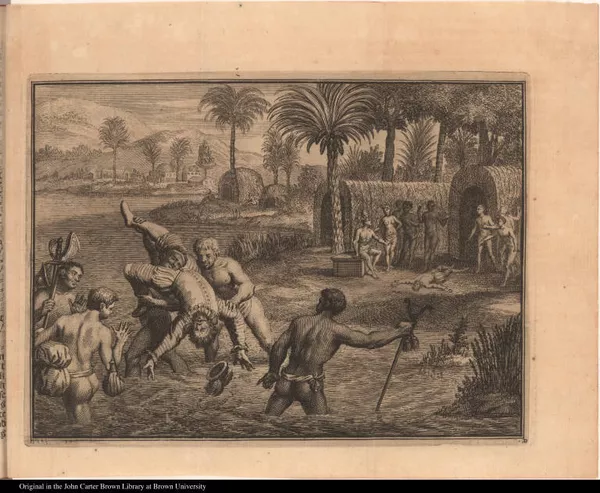

[Native Americans throw a European into a stream]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Divers Things

Sloane’s patron in Jamaica was Christopher Monck, 2nd Duke of Albemarle, the new governor. Monck purchased enslaved African laborers soon after disembarking, but more important in his decision to accept the governorship was likely his desire to repeat the fortune he had already made sponsoring underwater Caribbean salvage dives in the 1680s. Contrary to van der Aa’s depiction, most such projects engaged not Europeans but African and Amerindian divers to fish bullion from sunken Spanish treasure ships. While Sloane warned about the tall tales of fortune that seduced the credulous into investing in phantom treasure hunts, he brought several submarine curiosities back from Jamaica, fished from the depths by divers, including coral-encrusted coins and beams from Spanish ships.

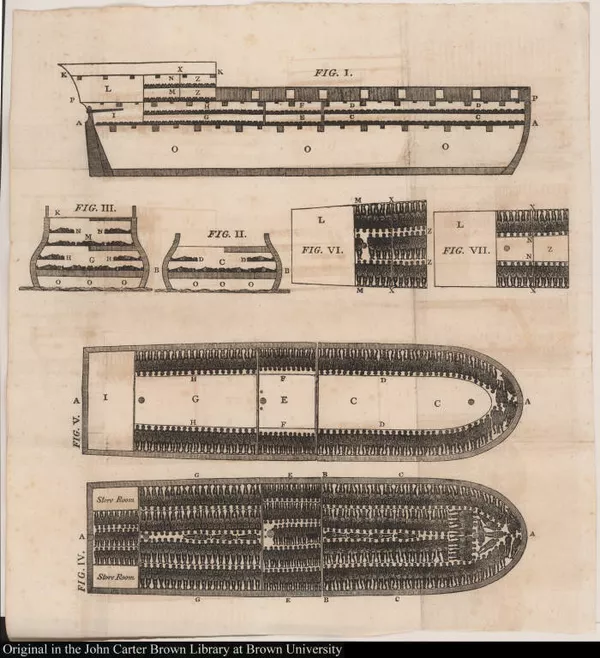

[Diagram of a slave ship]

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1African Voyages

This woodcut representation of the middle passage based on the slave ship Brookes was first circulated by British abolitionist campaigners in the 1780s. Although several anti-slavery pamphlets were published in the years around Sloane’s voyage, there was little broad-based political debate about the morality of the slave trade at that time. Many Africans transported from the Gold Coast (Ghana) to Jamaica were Akan-speaking Coromantees, a people well versed in the arts of war who played a prominent role in uprisings of the enslaved. Many Maroons were also Coromantees. Clarkson's image calls to mind the precision with which merchants conducted and calculated the slave trade to maximize profitability. Surviving ledgers in the Lincolnshire Archives record numerous deliveries to Sloane of hogsheads of sugar from Knollis and Mickleton, his wife Elizabeth’s plantations.

A trip to Jamaica

1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Torrid or Temperate?

Ward was the sharp-tongued London satirist who infamously described Jamaica as “the dunghill of the universe,” a phrase that conjured an image of vice and depravity on a cosmic scale. This was merely the most memorable statement, however, of a much more diffuse idea: that lying in the Torrid Zone, the West Indies were an arena of physical, moral and racial degeneracy. The pirate haven of Port Royal epitomized this anxiety: its destruction by earthquake in 1692 prompted several commentators to praise divine retribution in punishing sin. Sloane, by contrast, took pains to write about Jamaica as a temperate island entirely fit for English colonization. His account of the earthquake was wholly naturalistic. He was committed to seeing the island flourish as an English colony susceptible to scientific analysis and profitable management.

Jamaica, Americae Septentrionalis Ampla insula. Christophoro Columbo detecta

1680

-

p. 1

p. 1Island Reconnaissance

This map depicts the state of English settlement in Jamaica in the years before Sloane’s visit. Many early Jamaica maps note specific names and locations of planters, engaged in growing sugar, cacao and other crops. Sloane’s voyage came well before the heyday of sugar’s profitability in the mid-eighteenth century, and during the transition from indentured white servitude to enslaved West African labor. Repeated rebellions by enslaved Africans, the persistence of free Maroon communities, and the threat of natural disaster and foreign raids did not deter the English from pursuing this increasingly lucrative transition. While traveling from St. Iago de la Vega (Spanish Town) to St. Ann’s on the North coast, Sloane likely met Elizabeth Langley Rose. Their subsequent marriage brought income from sugar plantations directly into the family.

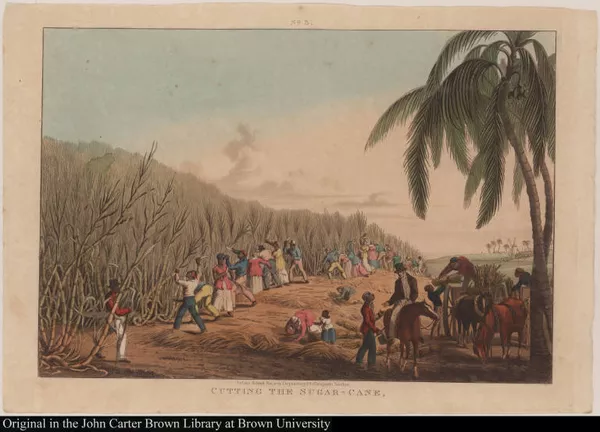

Cutting the sugar-cane

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Anatomy of a Sugar Island

This emancipation-era publication reprints images from Views of sugar production on Antigua (1823) by William Clark. This one is entitled “Shipping Sugar, Willoughby Bay.” Clark captured the environmental complex of the Caribbean plantation system. In depicting hogsheads of sugar being hauled to merchant ships, and ultimately European markets, Clark—likely a planter—drew diagrammatic attention to the relation between enslaved human labor, ox- and horse-power, and the harnessing of wind as a maritime energy source to make the sugar trade function. Where Sloane’s account of Jamaica was driven by a commitment to Baconian fact-gathering, later picturesque landscape views of Caribbean life—a response in part to mounting critiques of slavery’s inhumanity—artfully harmonized the elements of a society built on the systematic and legalized use of violence.

Venus's Fly-trap. Dionaea Muscipula.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Collecting Techniques

These illustrations of specially designed boxes for transporting seeds come from a set of instructions for field collecting issued by the British botanist John Ellis in the late eighteenth century. Already in Sloane’s day, however, it was common to issue travelers with instructions and even materials, especially paper for folding up and sending back specimens. Sloane’s London associate James Petiver routinely instructed correspondents to train enslaved Africans as collectors, since they often proved more skilled and physically venturesome than colonists. Slaves might be paid in money or in goods like rum. Petiver offered to pay enslaved collectors half a crown per dozen insects, and twelve pence per dozen plants, provided each specimen was whole and distinct. Sloane likely engaged both enslaved collectors and guides while in Jamaica.

Catalogus plantarum quæ in insula Jamaica sponte proveniunt, vel vulgò coluntur

1696

-

p. 1

p. 1The Naturalist as Man of Letters

Composed in Latin, Sloane’s first Jamaica publication was intended primarily for specialists as a guide to synonyms and previous accounts of Jamaican flora. Pages 134-135 show Sloane’s entry for Cacao. After acknowledging his friend John Ray as his source for the name, he lists previous botanical and travel writings that describe the species. Evident here is Sloane’s determination to present himself not just as a traveler or empirical collector, but a man of letters. His synonymy is also a testament to the wealth that enabled his collecting: he culled these references from books in various languages from his formidable personal library. Sloane hoped his natural history would be of practical use to colonists. But it was also part of his self-fashioning as a learned author in the republic of letters. Colonists in Jamaica complained, however, that they couldn’t read Latin.

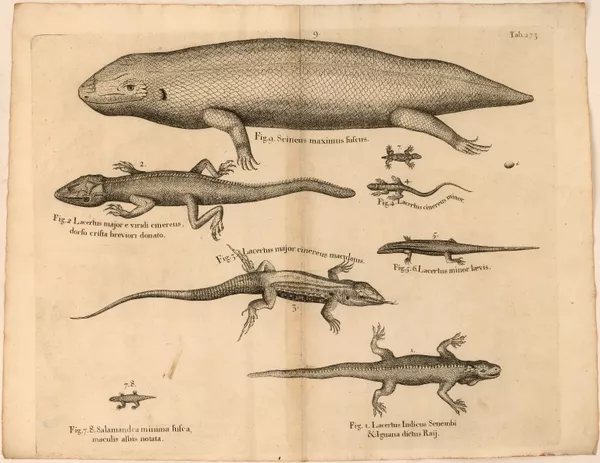

[Lizards, skink, salamander, and iguana]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Seeing Jamaica in London

Cacao provides an example of how Sloane envisaged the crucial role of illustrations in his ‘histories’ of species. Sloane’s published engraving is of a live plant, sketched in Jamaica in the 1680s by the Reverend Garrett Moore, whom he employed as he toured the island. But the engraving also combines sketches of preserved cacao pod bark and nut made c. 1699-1701 in London by a Dutch draughtsman named Everhardus Kickius, who drew Sloane’s numerous dry specimens for the Natural history. ‘Witnessing’ what grew in Jamaica thus combined both live and preserved specimens and was a transatlantic collaborative process that lasted several years. As a Baconian naturalist, Sloane was committed to depicting individual specimens rather than idealized composites. Linnaeus used these sketches to designate Theobroma cacao in 1753.

A voyage to the islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica

1707-1725

-

p. 57

p. 57Curious Plant Ethnography

While Sloane’s lavish engravings attracted considerable attention, they were accompanied by significant textual work. His entry on Cacao featured anatomical description, notes on the preparation of drinking chocolate, and extensive excerpted commentary on the cacao nut’s function as a form of money in Native American societies. It omitted to mention the role of enslaved Africans in harvesting these nuts in the Caribbean, however. This commentary served multiple purposes, such as showcasing Sloane’s learned ethnographic curiosity and appropriating Spanish commentary for English readers. Narratives of the ‘Scientific Revolution’ have often stressed the primacy of empirical knowledge and the importance of experience-based representations. But Sloane was determined to be viewed as a learned natural historian in the tradition of Renaissance humanism. In one instance where readers found fault with his illustrations, he suggested that his verbal descriptions were more reliable since, unlike the engravings, they were his own unmediated observations.

-

p. 620

p. 620Insectology’s Bodies

Sloane paid close attention to insect species in Jamaica, collecting numerous varieties. From being considered unclean (they were supposedly absent from the Garden of Eden) insects became recast in the seventeenth century as exemplars of God’s rational design in its minutest form, thanks to illustrated publications like Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1655). Insects, however, also threatened Sloane’s collecting project. Black ants, for example, devoured several of his hummingbird specimens. On one occasion, an enslaved woman removed a “chego” from Sloane’s foot. Insectology (as it was then called) also intersected with discussions of slavery. Sloane engaged with Jamaica planters and Royal Society associates in discussions of the causes of ‘worms,’ a medical problem that undermined Africans’ value as laborers. These engravings were probably made from preserved specimens back in London.

-

p. 640

p. 640Double Agents

Animals weren’t simply specimens in waiting: they were unpredictable agents who mediated between Jamaica’s English and African populations. Sloane delighted in telling stories about local creatures as well as describing and collecting them. This drawing of the Great Black-Bird appears to have been done from the life by Garrett Moore. After describing its anatomy, Sloane explains that it “haunts the Woods on the Edges of the Savannas … making a loud Noise, upon the sight of Mankind.” This warning call made hunting next to impossible, but it also meant that “when Negros run from their Masters … these Birds on sight of them as of other Men, will make a Noise and direct the Pursuers which way they must take to follow their Blacks.” The folk song “Chi chi bud-oh” preserves, by contrast, vernacular Afro-Caribbean catalogues of Jamaican birds.

Le More-lack, ou Essai sur les moyens les plus doux & les plus équitabl...

1789

-

p. 10

p. 10Evils of Chocolate

This abolition-era image shows a European rising from a table where chocolate is being consumed and raising a stick at an approaching African. “Sir Hans Sloane’s Milk Chocolate” – marketed not by Sloane but a London grocer named Nicholas Sanders – appears to have emerged as the world’s first brand drinking chocolate in the mid-eighteenth century. It was reputedly made from Sloane’s recipe and sold as an elixir for the stomach. Such salubrious claims had to counter long-standing concerns, however, about the physical and moral dangers of consuming chocolate. The Spanish associated it with native diabolism; commentators feared it would darken the skin; and Hogarth, anticipating Marsillac, linked its luxurious consumption with the injustice of slave labor in Marriage à la Mode part 4 (1745).

Nova plantarum americanarum genera

1703

-

p. 93

p. 93French Connections

After returning from Jamaica, Sloane sent duplicate plant specimens to his former Paris mentor, the taxonomist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort. According to Sloane, this exchange influenced the Minim friar Charles Plumier’s collecting trips to the West Indies and the production of this illustrated volume. Because Sloane was too busy to publish until 1707, some of Plumier’s species descriptions anticipated his own, although Sloane’s published engravings were rather more detailed. Sloane’s ongoing relationship with Tournefort reflected his careful cultivation of an extensive network of international scientific contacts, notwithstanding both intellectual and imperial rivalries. Like England, France was then a rising power in the Caribbean, thanks to the increased importation of African labor to harvest sugar. French raids were a recurrent threat in Jamaica in the late seventeenth century, and Saint Domingue would eventually outstrip the British Caribbean islands as the most lucrative of all American colonies.

Mariae Sibillae Merian Dissertatio de generatione et metamorphosibus ins...

1719

-

p. 89

p. 89“Myne Slaven”

In 1711, James Petiver purchased images of plants and insects for Sloane that had been painted by Maria Sybilla Merian in Surinam. Originally from Frankfurt, Merian traveled to South America with the Dutch East India Company in the 1690s and published several illustrated natural histories. These achieved lasting renown, especially for their ‘ecological’ combination of plants and animals, highly unusual for the time. Early visitors to the British Museum singled them out as being amongst the most beautiful albums in the collection. Like many colonial naturalists, Merian either bought or was given slaves (“myne slaven”), likely a combination of Africans and Indians, whom she engaged as guides and probably auxiliary collectors. Unlike Sloane and Petiver, however, she openly criticized the institution of slavery. Notice how different Merian’s depiction of Cacao is from Sloane’s.

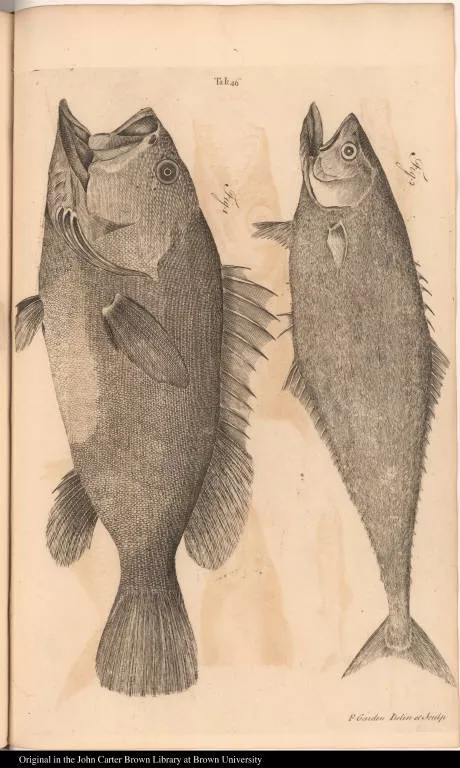

[Fishes]

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Universal Taxonomies, Private Interests

Browne was an Irish-born physician who traveled to Jamaica as sugar and slavery became increasingly profitable in the eighteenth century. Unlike Sloane, however, Browne’s botany dispensed with learned plant ethnographies and concentrated on plants’ sexual anatomy, as dictated by Linnaeus’ new system. Browne was among the first Anglophone authors to follow it extensively, and its principles were reflected in George Ehret’s illustrations for his book. Linnaeus used both Sloane and Browne as sources on Jamaican flora for his Species plantarum (Stockholm, 1753). But while naturalists aimed to draw together as many species as possible to create a universal taxonomy, botanizing in Jamaica after Sloane remained a fragmented rather than collective endeavor. In the 1790s, Thomas Dancer lamented the lack of support for a public botanical garden. This absence was an expression of enduring planter hostility to public institutions that might impinge on private interests.

A caution to Great Britain and her colonies

1767

-

p. 1

p. 1The Abolitionists’ Sloane

Benezet was a French Huguenot who settled in Philadelphia and became one of the leading early voices in transatlantic abolitionism in the 1750s. He was one of several authors who quoted Sloane’s graphic 1707 description of the torture and execution of Africans who rebelled in Jamaica. (In this section of this edition, where Benezet cites Sloane, the quotation actually comes from another writer.) Abolitionists like Benezet drew on Sloane’s credibility and alleged impartiality, now powerfully augmented by his status as the benefactor of the British Museum, as an unimpeachable eye-witness to the “inhumanity” of slavery. In so doing, they redefined the status of his account of slave punishments, which Sloane had produced as curious observations intended, if anything, to justify such treatment. Anti-abolitionists were quick to contest the reliability of Sloane’s eye-witness account.

2. African Culture: From Curiosity to Ambush

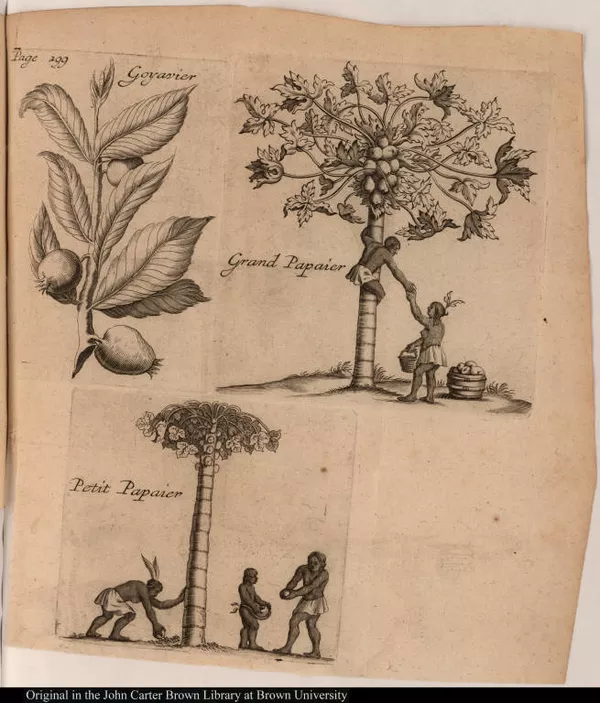

Goyavier; Grand Papaier; Petit Papaier

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Ancient Jamaicans

This anonymous depiction of indigenous Americans harvesting guava and papaya in the Caribbean draws our attention to the absence of Jamaican Tainos in Sloane’s time, decimated by disease and violent confrontation with the Spanish. By Sloane’s day, such harvests were performed by enslaved West Africans, whom he sought out as the living repositories of indigenous and Spanish knowledge of the island. Sloane noted the presence of recent Amerindian migrants in Jamaica and their hunting prowess but remained vague on their provenance. He was more concerned with the Taino. He brought back fragments of clay urns and indigenous human remains discovered in a cave near Red Hills. An English Protestant, he framed these as evidence of Spanish atrocities, keeping alive the ‘Black Legend’ of Spanish cruelty. Interestingly, he classified these urns in his Antiquities catalog, along with ancient British, Greek, Roman and Egyptian artifacts.

Arrivée des Européens en Afrique

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1African Animals and Environmental Transformation

Freret’s engraving portrays the encounter between Africans and Europeans on the West African coast as one mediated by the animals (parrots) offered to the new arrivals, possibly as gifts or an invitation to trade and exchange. The image appears ambiguous: it might be seen as heralding African natural mastery (hence the parrots, tusks, fish, monkeys, feathers and elephants at their command) or a fantasy of resistance-free European access to such bounty. By 1795, slave trade ships had for decades brought domestic animals to the Caribbean: guinea fowl and sheep (as well as guinea grasses) were an important food source. Freret’s image by contrast focuses on exotic specimens. Sloane made observations of both rare animals and livestock in Jamaica, noting African provenance where possible, making his Natural history an important document of Caribbean environmental transformation.

Christopher Columbus and his Sons Diego and Ferdinand.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Afro-Caribbean Harvests

By foregrounding the presentation of exotic fruits at the feet of English colonists in St. Vincent (the site of an important botanical garden) by a doubled-over African woman, this image seems to suggest colonial projections of painless access to local agricultural abundance and female obeisance therein. But in associating this woman with the harvest of local fruits, it also calls to mind the provision grounds run by Africans to feed themselves in lieu of proper provisioning by Caribbean planters. Sloane likely visited such grounds while in Jamaica and noted the cultivation of potatoes, yams and plantains by the enslaved. Such ‘gardens’ were spaces of enslaved agricultural autonomy that sustained African botanical traditions.

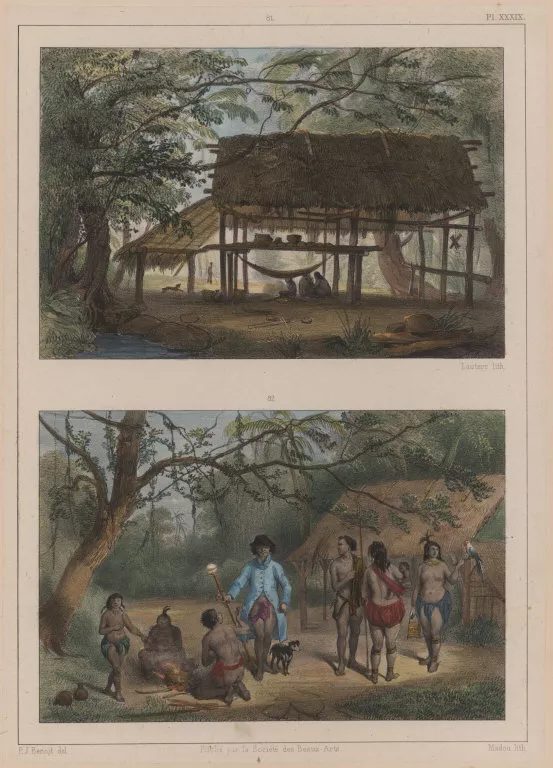

81. Un carbet. 82. Une famille.

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Market Exchanges

This image from the Belgian artist Benoit’s romanticized account of his Surinam travels recalls similar depictions of markets in St. Vincent by Agostino Brunias and Antigua by William Beastall. These markets were fundamental to the internal economy of Caribbean societies and already existed in Jamaica by Sloane’s time. It is likely that Sloane – who documented the provision grounds of enslaved cultivators – would have visited them, drawn by his curiosity about local flora and fauna. We know that his friend Henry Barham did so; representations, including Benoit’s, regularly feature white visitors mixing with enslaved and free Africans. Itinerant African traders known as higglers brought livestock, dairy and agricultural produce, rare animals and objects for commercial sale or exchange in kind. Sloane may have purchased specimens from such traders.

Hortus Americanus: containing an account of the trees, shrubs, and other...

1794

-

p. 1

p. 1Botany Among the Enslaved

Barham was a physician and planter based in Jamaica in the early eighteenth century. He was Sloane’s closest correspondent on the island, and a dutiful annotator of the Natural history of Jamaica (Sloane incorporated several of his corrections and additions in volume two). Barham’s own natural history was published posthumously decades after his death. His manuscripts reveal how his residency in Jamaica gave him a more detailed appreciation of African knowledge of the island’s flora and fauna than Sloane’s. For example, Barham acknowledged enslaved expertise in medicine, including the practice the English referred to as Obeah, and used African names where Sloane adopted only English and Latin terms. He supplied Sloane with numerous specimens and some singular curiosities, including bullets and clothing that he said came from Jamaica’s Maroons.

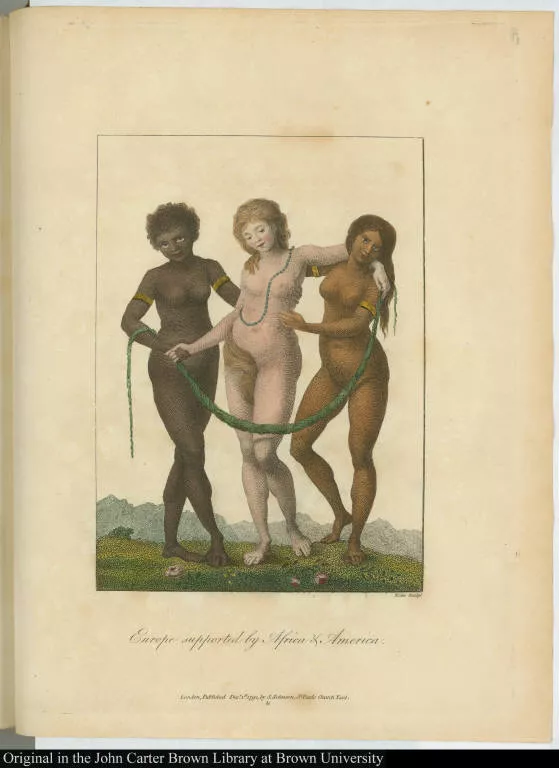

Europe supported by Africa & America.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Snake Charmers

This image, from the Scottish-Dutch soldier Stedman’s narrative of his Surinam journey, depicts him directing three African men to kill and flay a large snake named Aboma. It is not clear if these men are slaves or if Stedman is paying them for their services. Perhaps unwittingly, the image emphasizes European passivity and African dexterity in the face of American fauna. Collectors like Sloane would often have turned to African or Indian hunters as sources of elusive or dangerous specimens. Sloane recounted stories of Indian snake-charmers in Jamaica and, evidently eager to emulate such mastery, attempted to ship a live six-foot yellow snake back to London. He fed it carefully, but it escaped its makeshift container and was shot dead by the Duchess of Albemarle’s startled attendants.

Europe supported by Africa & America.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Traduttore/Traditore

Even when compensated, virtually no Africans engaged by colonizers to collect were individually credited in published works of natural history. The outstanding exception is “the Celebrated Graman Quacy,”—otherwise known as Kwasímukámba—who secured his freedom by helping Dutch soldiers hunt down runaway slaves in Surinam. Quacy had the Quassia Amara named after him by Linnaeus, was sometimes referred to as “Professor of Herbology in Surinam” and was presented to Prince Willem V of Orange in the Hague in 1776. This engraving by William Blake portrays him dressed as a gentleman, with a Dutch fort in the background (notice how Quacy’s clothes echo the colors of the Dutch flag). Stedman, who encountered him in Surinam, described him as “very proud” and “very saucy” and “not unlike one of the Dutch generals.”

Acts of Assembly, passed in the island of Jamaica, from the year 1681 to...

1787

-

p. 1

p. 1Acts of Assembly

When Sloane visited Jamaica, legislation for the discipline and punishment of enslaved Africans was becoming increasingly important, given the expansion of the black population. After the Restoration, a 1661 proclamation had declared white settlers “free Denizens of England,” while the first comprehensive act concerning slavery in 1664 (based on legislation in Barbados in 1661) described “Negroes” as “Heathenishe brutish and uncertaine and dangerous.” This justified laws for their coercion, punishment and restriction of movement as “protection” from “arbitrary cruell and outragious [sic]” treatment. In response to further rebellions among the enslaved and continual agitation by the Maroons, these laws were strengthened in 1696 (to include anti-poisoning measures, for example). This legislation reveals how difficult it was for colonial authorities to police the movement and co-operation of Africans in Jamaica. Sloane described the means of punishing enslaved rebels in his Natural history but said almost nothing about the rebellions themselves or Maroon resistance.

A voyage to the islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica

1707-1725

-

p. 179

p. 179Jamaican Curiosities

The composition of this engraving reflects Sloane’s multiple preoccupations as a naturalist and collector: the desire to document local customs, link natural materials and artificial productions, and compare the craftsmanship of the world’s different peoples. It features (front to back) South Asian, Jamaican and West African stringed instruments. It punningly juxtaposes a Jamaican luteus plant (“5”) with which Africans cleaned their teeth: Sloane described what he called the Jamaican “Strum Strum” as being an “imitation of lutes.” Sloane brought this instrument back from Jamaica in 1689 and had it drawn by Kickius. He described it as consisting of “small gourds fitted with necks, strung with horse hairs, or the peeled stalks of climbing plants or withs.” The means of its acquisition is unknown: Sloane may have paid for it, exchanged for it, or taken it through coercive means.

-

p. 70

p. 70Music in Transit

Sloane claimed to have witnessed performances of African dance and music in Jamaica. This remarkable transcription, made by a man named Baptiste, is one of the earliest known recorded pieces of African music in the Americas. It notes three West African variants identified as “Angola,” “Papa,” and “Koromanti.” The ethnomusicologist Richard Rath has argued that these embody an early stage in the development of African-American music, part pidgin, part Creole, including both West African elements and West Indian fusions. The words suggest a variety of possible themes: sexuality, the spirits of dead ancestors, children at play and physical comfort. While other Caribbean travelers described African music, Sloane’s collection of instruments and transcriptions was without precedent and perhaps paradoxical. His written descriptions emphasized the base passions of such performances, but he nevertheless took pains to preserve their artifacts.

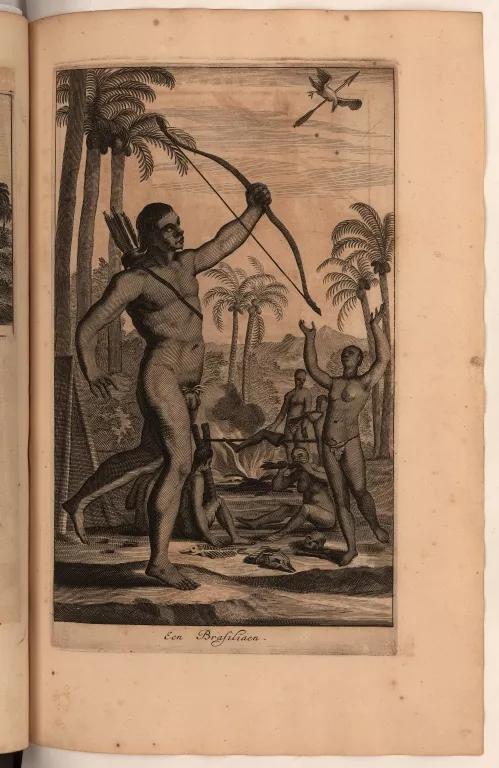

Een Braziliaen.

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Instruments of Rebellion

Nieuhof was a traveler who worked for the Dutch East India Company and held official positions in India and Ceylon. He was best known for his writing on China, but also visited Brazil. Unlike Sloane’s images of African instruments and music in the style of isolated specimens, this image portrays Africans in Brazil dancing and playing a calabash and tambourine. Sloane noted in 1707 that the British had banned the use of trumpets and drums in Jamaican festivals, in recognition of their military use in West Africa and their ability to foster solidarity and potentially rebellion among the enslaved. Their prohibition doubtless heightened their value as curiosities. Sloane’s ‘Akan Drum’ – one of the drums used to exercise Africans on the Middle Passage, sent to him from Virginia by a man named Clerk after 1730 – is held by the British Museum.

81. Un carbet. 82. Une famille.

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1African Healing

This image features Benoit’s encounter with a female African practitioner in Surinam of what he called “sorcery”: “Mama Snékie” or the “Mere des Serpents,” also known as “Water Mama”(Benoit’s guide is also in the frame). Benoit regarded African healers as charlatans, but was deeply curious about them and their tools. “Tata, Tata, helpie wie,” he recorded her words, which he translated as “God, help me.” Female African healers were regarded as powerful and sometimes dangerous figures in African-American societies. While rejecting their belief systems, settlers often turned to them for medical assistance, acknowledging their greater experience with local plants and animals. Sloane ignored such ‘magical’ practices in Jamaica and wrote dismissively of African healing techniques. However, he did record fragments of the conversations he had with Africans about disease and medicinal plants while in Jamaica.

A new and accurate description of the Coast of Guinea, divided into the ...

1705

-

p. 1

p. 1Fetishism

The Dutch traveler Bosman’s account of European interactions with Akan gold traders on the West African coast has been identified as a crucial moment in which Europeans first began formulating their concept of the ‘fetish.’ The origins of later theories of fetishism, such as Marx’s theory of commodity fetishism, have been traced to these accounts that describe African ascriptions of active spiritual powers to artificially made objects. Commentators in the eighteenth-century West Indies likewise identified the practice of Obeah as a transplanted form of West African sorcery or witchcraft that deployed carefully constructed obis as charms for protection and attack. Unlike other travelers, Sloane, perhaps surprisingly, says almost nothing about such practices or objects in Jamaica. He was likely ignorant as to the full extent of their usage and significance but may also have deliberately ignored them.

The history of Jamaica. Or, General survey of the antient and modern sta...

1774

-

p. 479

p. 479Obeah

Long was a Jamaica-based English planter whose published survey of the island included a racialized defense of slavery as a force for civilizing Africans, while also criticizing planter corruption. He described Jamaica’s civil and natural history and documented many individual plant and animal species, emulating Sloane and citing him approvingly. In the aftermath of the significant slave uprising known as Tacky’s Rebellion in 1760, he wrote warningly of the role of “Obeiah-men” as “pretended sorcerers” who emboldened African resistance through supernatural belief in physical invulnerability. The notion that such “priests” were charlatans credited only by credulous Africans may help explain Sloane’s neglect of this phenomenon. Since eighteenth-century scientific writers increasingly contrasted enlightenment botany to ancient druidical magic, Obeah doubtless struck Europeans as a highly atavistic if also threatening form of magical practice.

Notes on the two reports from the Committee of the Honourable House of A...

1789

-

p. 1

p. 1Contested Powers

The anti-abolitionist Stephen Fuller, Jamaica’s agent in Westminster, was Sloane’s grandson-in-law (Elizabeth Rose, Sloane’s step-daughter, had married into the Fuller family of Sussex in 1703). His reports warned about the dangers of Obeah. While European collectors like Sloane gathered plants and animals for both cosmological and practical purposes (taxonomy and pharmacopoeia), Africans mobilized similar specimens and objects for their own purposes: healing, poisoning, religious worship and trance-based spiritual communication with ancestors. They used grave dirt, animal parts, feathers, rum, eggshells, blood and various plants in their preparations. The British attempted to ban their use by law after Tacky’s Rebellion and Fuller described the execution of Obeah-men bearing feathers and other regalia. He also cited Sloane and Barham as sources on the dangers of African poisoning.

[upper left] Jack receiving Obi. [upper right] Jack escaping from Prison...

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Three-Fingered Jack

This novel offered one version of the celebrated exploits of a formidable fugitive Afro-Jamaican named Jack Mansong (“the terror of Jamaica”) who defied recapture until he was finally killed by the Maroon allies of the British in 1781. This contest is represented in the novel’s early frontispieces, which also depict the obi Jack reputedly carried around his neck. The Kingston surgeon, William Moseley, claimed that Jack’s obi consisted of a goat’s horn containing grave dirt, ashes, the blood of a black cat and human fat. It was said that Jack received his obi from an old cave-dweller in the Blue Mountains. His story was made into a stage play and performed in London in 1800 and he became a romantic hero as debate raged over the abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire.

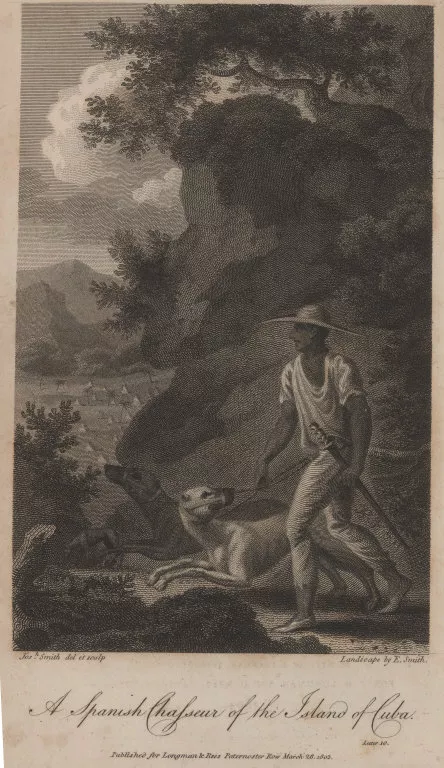

A Spanish Chasseur of the Island of Cuba

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Trees, Memory and Identity

“Old Cudjoe making peace” is a British commemoration of the peace treaty they signed with Jamaica’s Maroons, led by Captain Cudjoe, in 1739. The background suggests the crucial role trees played in Jamaican life. Sloane’s drawings of trees (done by Garrett Moore) isolated them from their environmental and human contexts, rendering them as delocalized specimens and potential resources for export as timber. But trees performed powerful functions in Afro-Jamaican society. Africans spoke of duppies (spirits) haunting cotton and almond trees; Maroons placed defensive charms in specific trees; Matthew ‘Monk’ Lewis recorded how cotton, cocoa and mahogany trees marked important places and moments in the ‘Anansy’ stories his slaves recounted; and Cynric Williams told of one African who claimed compensation from a master who had cut off the branch of a calabash tree that his grandfather had planted.

Memoirs and anecdotes of Philip Thicknesse

1788

-

p. 1

p. 1Ambush and Camouflage

Thicknesse was a British soldier and author who described British “astonishment” at the camouflage and ambush tactics of Maroons in the 1730s. The British recognized the Maroons by treaty in 1739 in return for a controversial agreement to return runaway slaves. Maroons often practiced what they called “Science” (similar to Obeah) against their enemies. The 1739 treaty acknowledged Maroons’ unequalled mastery of Jamaica’s mountainous landscape. Sloane avoided Maroon country on his travels and his use of the term “ambush” may signal his awareness of their camouflage prowess. Jamaican Jonkonnu parades to this day feature a camouflage-style figure called “Pitchy Patchy.” The origins and significance of this figure are ambiguous. Although compared by the British to their folk character called “Jack in the Green,” it probably derives from West African masquerade traditions and may also be a form of anti-Maroon satire performed by slaves and their descendants.

Credits

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library