1. Representing Nuns

R. de la M.R.M. Maria Ignacia de Azlor, y Echeverz, Fundadora Patrona, y...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

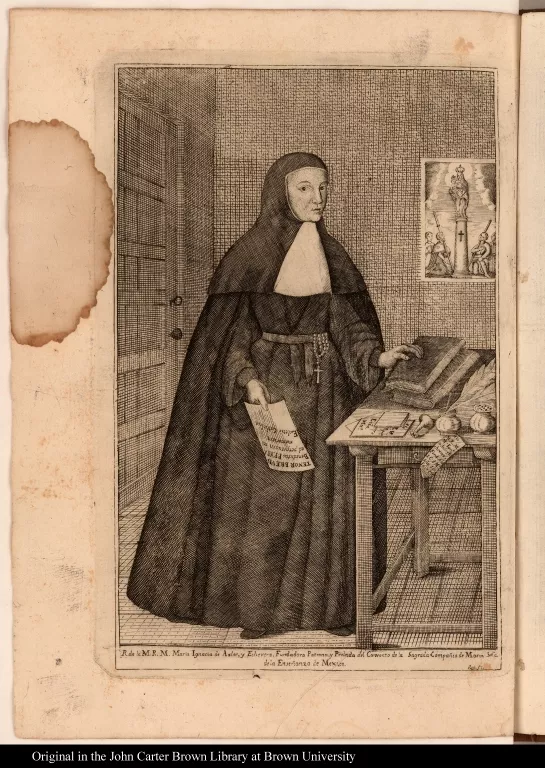

p. 1This portrait of María Ignacia de Azlor y Echeverz (1715–1767) illustrates an account written by members of the convent she founded in Mexico City, La Enseñanza, whose nuns devoted their lives not to solitary contemplation, but to running a school for girls. The Mexican artist, José Simón de la Rea, depicted María Ignacia wearing a rosary at her waist and accompanied by objects pertaining to her vocation as founder and abbess. In one hand, she holds a brief of foundation from Pope Benedict XIV, and on the desk beside her are an inkwell, plumes, a seal, books, and letters bearing her name. In keeping with María Ignacia’s commitment to holy poverty, the wall behind her is adorned with a single image: Our Lady of the Pillar, patron of the convent, as she appeared in Spain to the apostle Saint James (the bearded figure at the foot of the pillar) and the newly converted. Their presence here may refer to the conversion of indigenous peoples in colonial Mexico.

La M. Iosepha Petra Iuana Nepomucena de Sr. S. Miguel. Religiosa profess...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1This engraving illustrates a letter commemorating the short life of Josepha (or Josefa) Petra Juana Nepomuceno de Señor San Miguel (1741-1757), a nun from a prosperous Mexican criollo family, who died at age sixteen. In the engraving, Josepha dons the simple habit of a black-veiled Dominican nun. The crown on her head denotes her status as a bride of Christ and an imitator of the Virgin, the Queen of Heaven. The engraving’s iconography relates closely to the painted portraits of crowned nuns that were produced frequently in eighteenth-century Mexico. As in other representations of crowned nuns, Josepha bears upon her chest an escudo (a shield) depicting a holy figure, in this case, the Virgin of the Rosary, to whom the Dominicans were especially devoted. (See also the Mystical Marriage of Rose of Lima in the present exhibition.) Complementing the escudo’s imagery, Josepha wears a long string of rosary beads, which allude to her enthusiastic embrace of Dominican practice. She is depicted as young and beautiful: the epitome of the virginal innocence described throughout the Carta.

Relig[io]sa gero[ni]ma Sor Juana Ines de la [Cruz] ...

1651-1700

-

p. 1

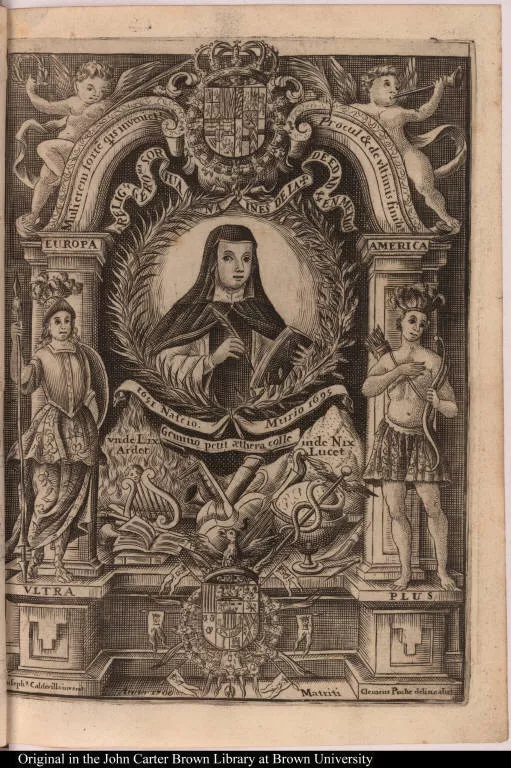

p. 1In this engraving, the great Mexican poet Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651-1695) appears holding a pen and a book, denoting her status as an author. She is framed by laurel leaves and other allusions to her literary fame. Beneath her portrait, figures labeled EUROPA and AMERICA stand upon the bases of columns, which bear the words VLTRA and PLUS. The engraving thus illustrates Spain’s imperial motto (Plus ultra refers to going beyond the pillars of Hercules that purportedly signaled the end of the known world) and highlights Sor Juana’s importance on both sides of the Atlantic. As indicated by the full title of Sor Juana’s posthumous works, contemporaries hailed her as a “tenth muse”: a woman whose poetic achievements rivalled those of the nine classical muses. Her status as an exception to her sex is reinforced by the Latin inscription above her portrait: “You will not find anyone to equal the strong woman you find here.”

Yet the engraver, the Spaniard Clemens (or Clemente) Puche, mitigated this emphasis on Sor Juana’s purportedly masculine strength by depicting her as a generically delicate feminine beauty cloaked in a religious habit. Unlike Puche, who probably had little knowledge of Sor Juana’s physical features, several eighteenth-century Mexican artists portrayed her as a woman with a dark, distinctive brow and an intense outward gaze. There is evidence to suggest that those artists had access to a (now lost) portrait painted of Sor Juana during her lifetime, and perhaps even to a portrait that the nun painted of herself.

Discurso theologo-juridicio, que escrive Fr. Miguel de S. Agustin, procu...

1718

-

p. 1

p. 1Teresa of Ávila (1515-1582) was, together with Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556), the most influential saint of the Spanish Catholic Reformation: the Church’s response to the “threat” of Protestantism and a movement to embrace what were deemed the original Christian ideals. Teresa founded the reformed, or discalced (literally, “barefoot”), branch of the Carmelite order, renewing its commitment to poverty and religious contemplation. When Teresa was made a saint in 1622, Church officials hailed her as a woman who had heroically transcended the supposed weakness of her sex, and women and men alike modeled their spiritual lives upon her example.

In the tract displayed here, Teresa’s portrait functions as a means of granting authority to male Carmelite friars (the convento in the title refers to a community of men) who disputed a tax levied on the profits they made from farmland in New Spain. The engraving is modeled directly upon the portrait of Teresa that was painted from life in 1576 by the Discalced Carmelite artist, Fray Juan de la Miseria. When she saw that portrait, the aging Teresa apparently lamented that the painter had made her “look ugly and tired.” Yet because it was the only pictorial record of Teresa’s physical features, it was revered by the faithful and served as the foundation for images of Teresa across the Spanish world.

2. Journeys

La Ve. Me. Maria de Iesus de Agreda. Predicando a los Chichimecos del Nu...

1701-1750

-

p. 1

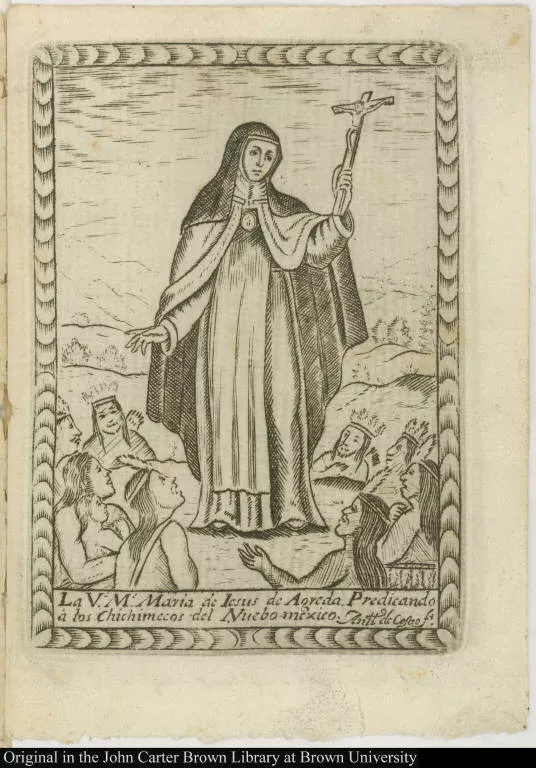

p. 1This engraving illustrates an account of Sor María de Ágreda’s (1602-1665) celebrated bilocation to the province of New Mexico, where she was believed to have preached without ever bodily leaving her convent in Spain. First published in 1631, the account was written by the Portuguese friar, Alonso de Benavides, who had worked in New Mexico and sought to strengthen missionary efforts there. According to Benavides, the indigenous peoples of New Mexico corroborated the story of María’s miraculous journeys, describing a woman clad in blue (the color of the nun’s cloak) who had preached to them and aided in performing baptisms. Benavides affirmed that, in her bilocations, María worked to evangelize the Jumanos and other groups in what is now northern Mexico and the southwestern United States. In the engraving shown here, however, María preaches to the “Chichimecos”: a Nahuatl term appropriated (and misunderstood) by the Spaniards, who used it in characterizing the peoples of New Mexico as “uncivilized.”

Exemplo de todas las virtudes. Y vida milagrosa de la venerable madre Ge...

1713

-

p. 208

p. 208The nun Gerónima (or Jerónima) de la Asunción (1555-1631) was renowned in her lifetime for the historic journey she undertook at age sixty-five. In 1620, she left her convent in Toledo, Spain, and embarked upon a year-and-a-half long voyage to found the first women’s convent in the Philippines. En route, she stopped for several weeks in Seville, where her portrait was painted by the great Spanish artist, Diego Velázquez. She then crossed the Atlantic and spent six months in Mexico before embarking again for Manila, where she triumphed in her mission.

This engraving by the Mexican artist Joseph (or José) Mota portrays Gerónima as an emaciated figure, her face creased with wrinkles and mouth sunken with age. At her side are a skull, hourglass, and crucifix, and before her lie various devices that she supposedly used to punish her body: chains, a whip, and a crown of thorns. Mota’s portrait thus contrasts markedly with the far more famous depiction of Gerónima by Velázquez, who portrayed her as a commanding figure staring at the beholder and holding her cross like a weapon. Mota would have been too young to have met Gerónima, and he seemingly based his image on textual accounts. The engraving and the book in which it appears formed part of a broader, if unsuccessful, movement to have Gerónima made a saint; she is also the subject of Bartolomé de Letona’s Perfecta religiosa in the present exhibition.

Modo de andar la Via-Sacra

1793

-

p. 2

p. 2This Crucifixion engraving adorns a diminutive booklet – one small enough to be carried or put into a pocket – that explains how to perform the stations of the cross. The text sheds light on how nuns and other members of the faithful perambulated inside churches. It provides precise instructions for the reenactment of Christ’s march to Calvary, indicating how many steps to take for each station: for example, eighty steps in emulation of Christ falling under the weight of the cross and seventy steps in commemoration of his encounter with the Virgin. Fittingly, these instructions for the literal and spiritual imitation of Christ’s journey are based upon the writings of Sor María de Ágreda (1602-1665), the Spanish nun who supposedly undertook mystical voyages to the Americas, where she preached the gospel.

Venerable Madre Maria de Jesus de Agreda. Redondez de la tierra y de los...

-

p. 13

p. 13This is a rare manuscript copy of an extraordinary cosmographical treatise by Sor María de Ágreda (1602-1665), the “lady in blue” who was said to have preached miraculously in the Americas without ever physically leaving her convent in northern Spain. In the treatise, María describes the earth, its continents, and its inhabitants as shown to her by angels. Despite its purportedly divine origins, her account of the earth’s geography reveals her study of scientific works such as Peter Apianus’s Cosmographia (1524), which was available in Spanish translation (the JCB has several early copies). Far less scientific was María’s description of those who lived outside Europe. Clearly dependent upon ancient and medieval descriptions of far-off places, María believed that the peoples of Asia, Africa, and the Americas were “barbarous”: “they are hairy and … the tallest are eight yards high, and some of them are very savage; there are others who are dwarfs, only half a yard high.” In keeping with her desire to preach the gospel, however, she also affirmed that “they have souls, as I do … and they are worth the same.”

3. Sacred Images

Vita della beata Rosa di Santa Maria, Peruana, del Terzo ordine di San Domenico

1668

-

p. 5

p. 5This image literalizes nuns’ status as brides of Christ. Like Saint Catherine of Siena before her, Rose of Lima (a Dominican tertiary, or lay sister, 1586-1617) married the Lord in a mystical ceremony. One Palm Sunday, Rose went to pray before an image of the Virgin of the Rosary: a subject of particular devotion to the Dominicans. As Rose prayed to the image of holy mother and child, a miracle occurred. Christ turned to Rose and said, “Rose of my heart, be my bride” (as shown in the Latin inscription here). According to the Vita, Christ gazed “almost with desire [at the nun],” and his words “penetrated … the depths of her heart.” In illustrating this exchange, the engraver, Giovanni Federico Pesca, conveyed the erotic quality of Rose’s vision, in which Christ, even as a child, assumed his place as beloved bridegroom. The rose garland that surrounds the figures alludes to Rose’s name, her devotion to the rosary, and her purity, of which her mystical marriage – a union of spirit rather than flesh – was the ultimate example.

When the Vita was first published in 1665, Rose was not yet an official saint. The Vatican beatified her (giving her the title of “blessed”) in 1667 and declared her a saint in 1671, making her the first person born in the Americas to receive universal veneration by the Church. The Vita is the only Italian-language work in the present exhibition; it was published in Naples, which was ruled by the Spanish crown from 1504 until 1713.

V. R. de la Milagrosa Ymagen de Na. Sa. de Sn. Juan de los Lagos

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1This engraving of Our Lady of Zapopan depicts an imagen de vestir: a sculpture meant to be clothed and adorned. Catholic decrees throughout the early modern period warned that dressing sacred sculptures in elaborate finery came perilously close to the sin of idolatry. From the Church’s perspective, the problem of idolatry would have seemed especially relevant to the Mexican city of Zapopan, which had functioned in pre-conquest times as a pilgrimage site, where the populace paid tribute to Teopintzintl, the Tonala Child God. Yet in Zapopan and across the Spanish world, members of the Catholic faithful and even clergymen themselves continued the practice of clothing religious sculptures, outfitting them in accoutrements that became ever-more elaborate over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

It was common for nuns to clothe such sculptures and to display them on altars resembling the one shown here, which is garnished with candles, flowers, curtains, and a brocade frontal. Like many Catholics at the time, nuns sought to ornament sculptures of the Virgin in a manner befitting her status as the Queen of Heaven. Toward that end, they sewed and embroidered sumptuous garments for the sculptures; made them wigs of long, real hair; and festooned them with jewels and crowns. In so doing, they helped to construct a visual culture in which rich material objects were placed at the center of religious devotion.

[Interior of a church]

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1This engraving depicts the Lord of the Miracles, a wonder-working image in the church of the Lima convent of the Nazarenas. According to tradition, the Lord of the Miracles was painted in 1651 by an Afro-Peruvian slave, and its power was revealed when it withstood a series of earthquakes. Having begun their institution as a humble house for lay women in the mid-seventeenth century, the Nazarenas worked hard to establish their convent on the site of the miraculous image, which became the official patron of Lima in 1715. They inaugurated their new convent twelve years later, becoming fully cloistered members of the Discalced Carmelite order and custodians of the most important shrine in Lima.

The engraving here shows the Lord of the Miracles at a time when its powers – and the piety of the nuns who housed it in their church – were deemed more necessary than ever. In 1746, a catastrophic earthquake and tsunami nearly destroyed Lima and the nearby port of Callao. The Lord of the Miracles survived, even as the walls of the church around it crumbed. This engraving commemorates the rebuilding of the church twenty-five years later, when it was constructed as a Neoclassical structure whose magnificence was considered appropriate to the image marvelously able to withstand even the most violent movements of the earth.

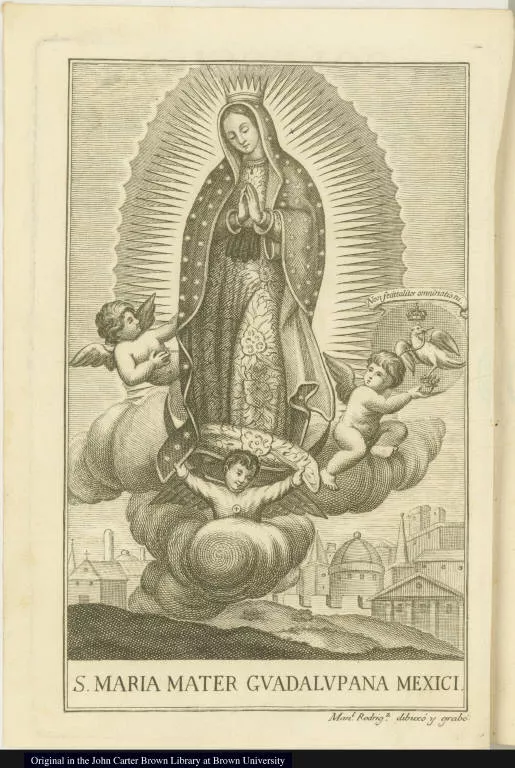

S. Maria Mater Guadalupana Mexici

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1No less than other members of the faithful, nuns in colonial New Spain expressed ardent devotion to the Virgin of Guadalupe. Tradition has it that the Virgin of Guadalupe first appeared to an indigenous Mexican peasant, Juan Diego, on a hill near Mexico City in 1531. She spoke to him in Nahuatl, his native language, and instructed him to have a church built on the site. The Archbishop, Juan de Zumárraga, dismissed the story until an even greater miracle occurred: when Juan Diego opened his cloak before the cleric, roses fell from it, and the Virgin herself appeared, imprinting her image upon the cloth. That “original” image was the prototype for the Guadalupe shown here and for hundreds of other devotional images.

The cult of the Guadalupana (as the Virgin of Guadalupe is sometimes known) grew steadily throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and Pope Benedict XIV declared her the official patron of New Spain in 1754. Although produced in Spain, the engraving displayed here highlights the Virgin of Guadalupe’s status as a Mexican figure of devotion. The Latin inscription above the eagle devouring a snake (a symbol of Mexico City) reads, “He hath not done in like manner to every nation,” a passage from the Psalms that, in this context, refers to the divine favor enjoyed by Mexico. At the bottom of the engraving, the subject is identified as “Saint Mary Guadalupana, Mother of Mexico.”

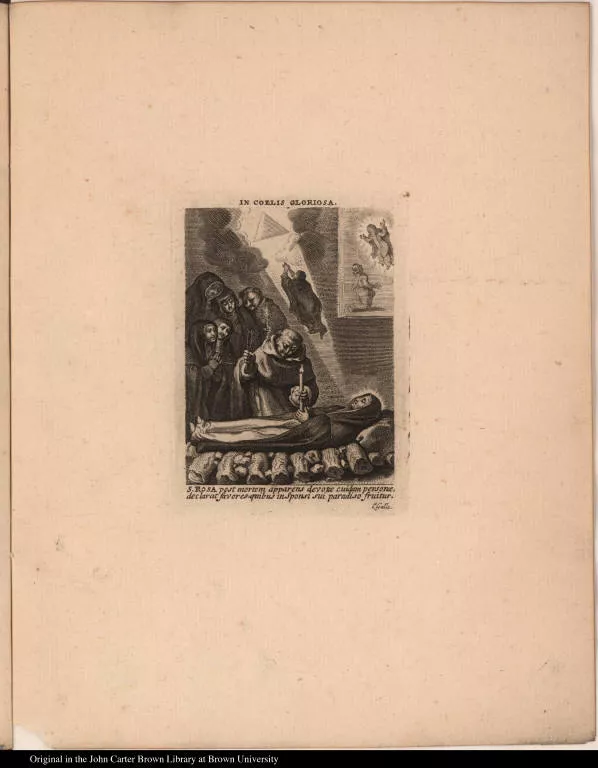

In coelis gloriosa.

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1This engraving depicts Rose of Lima (1586-1617) whipping herself in demonstration of the penitence for which she became revered. Her body is stripped almost naked, and her shorn head bears a crown of thorns. Beneath her lie the hard logs that reportedly served as her bed, and, on the shelf before her, the skull, hourglass, and book symbolize her meditation on the brevity of earthly life. Also on the shelf is a sculpture depicting Christ on the cross: the inspiration for Rose’s penitence and the model of suffering that she, like other holy women and men, sought to imitate. The print tacked to the wall behind alerts the viewer to Rose’s reward for her penitential practice. This picture within a picture depicts the Virgin Immaculate holding the Child Christ, alluding to their miraculous appearance to Rose, who married the Lord in a mystical union (see also the Mystical Marriage of Rose of Lima in the present exhibition).

4. Divine Love

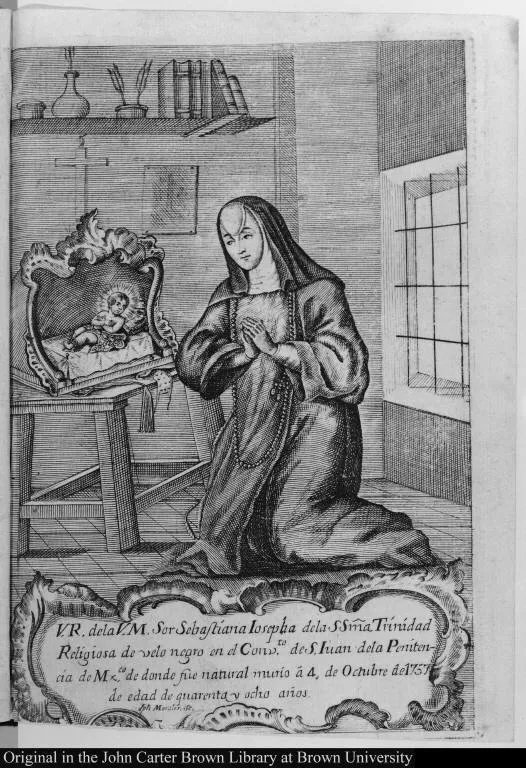

V. R. dela V. M. Sor Sebastiana Iosepha dela SSma Trínídad Religiosa de ...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1As suggested by the title of her biography, Sebastiana Josepha (or Josefa) de la Santísima Trinidad (1709-1757) was praised by her religious superiors for the intensity of her penitential practice, which involved whipping herself, refusing sleep, and fasting ceaselessly. In fact, Valdés’s biography suggests that Sebastiana starved herself to death at age forty-eight. Yet the engraving shown here makes only scant reference to her corporeal self-punishment: a whip and a penitential chain rest on the table beside the comely, youthful Sebastiana, who folds her hands in prayer.

Rather than penitence, the engraver emphasized Sebastiana’s devotion to the child Christ. Like many nuns, Sebastiana kept a sculpture of the infant Christ in her cell. According to a story recounted by Valdés, the sculpture performed a miracle which demonstrated the divine favor granted to Sebastiana: the image grew in size, in the manner of a real child. In her adoration of the holy infant, Sebastiana adhered to the devotional practice of her convent, whose nuns expressed particular reverence for another Christ child sculpture, the Santo Niño de San Juan (the Holy Child of Saint John). As Valdés has it, the Santo Niño saved the convent church during an earthquake, when it held up, “with two fingers,” the archway beneath one of the altars.

Villancicos, que se cantaron en la Santa Iglesia Metropolitana de Mexico...

1676

-

p. 5

p. 5The woodcut shown here provides a gloss on the carols that the poet and nun, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651-1695), wrote in celebration of the doctrine which proclaimed that the Virgin had been conceived without original sin. Unlike many of the more elegantly produced images included in the present exhibition, this woodcut would not have been designed to illustrate a specific text. Instead, it is a standard image of the Immaculate Conception – one in which the Virgin stands on the crescent moon, her hands clasped in prayer and head crowned by stars – and it was probably used in a number of seventeenth-century books and pamphlets. This image of the Virgin surrounded by angelic musicians was, however, especially appropriate for Sor Juana’s carols, verses set to music in which singers praised the mother of God for vanquishing the “fierce dragon,” itself depicted at her feet.

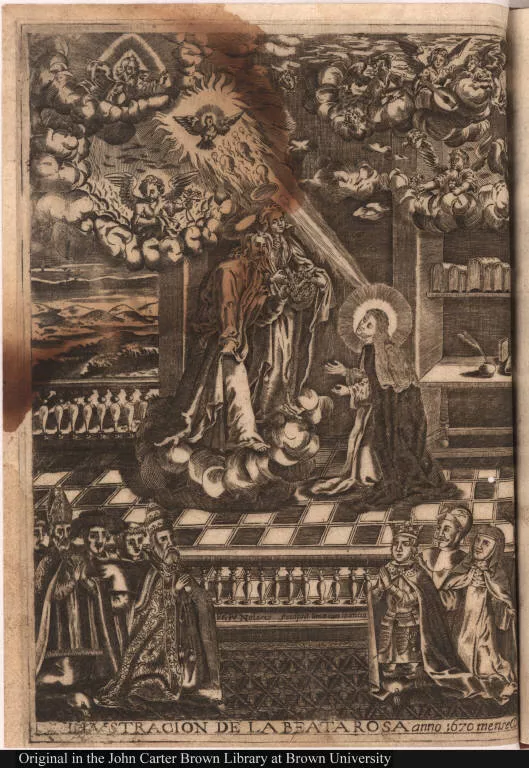

Illustracion de la Beata Rosa

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1This engraving adorns a book celebrating Rose of Lima’s (1586-1617) beatification in 1667, when the Vatican granted her the official status of “blessed” and thus paved the way to declaring her a saint. In the composition, Rose receives a crown of roses from Christ and the Virgin, a gift referring to her name and signaling the divine favor she enjoyed. The engraving also alludes to the supernatural illumination that infused Rose with perfect knowledge of sacred mysteries such as the Trinity (figured by Christ, God the Father, and the dove of the Holy Spirit): knowledge that equaled or surpassed the works of learned theologians (represented by the books on the composition’s right-hand side). Although difficult to identify with precision, the figures below bear witness to Rose’s holiness. They include a tonsured Dominican friar (a member of the order that Rose joined as a tertiary) and a man in a papal tiara (probably Clement IX, who oversaw Rose’s beatification).

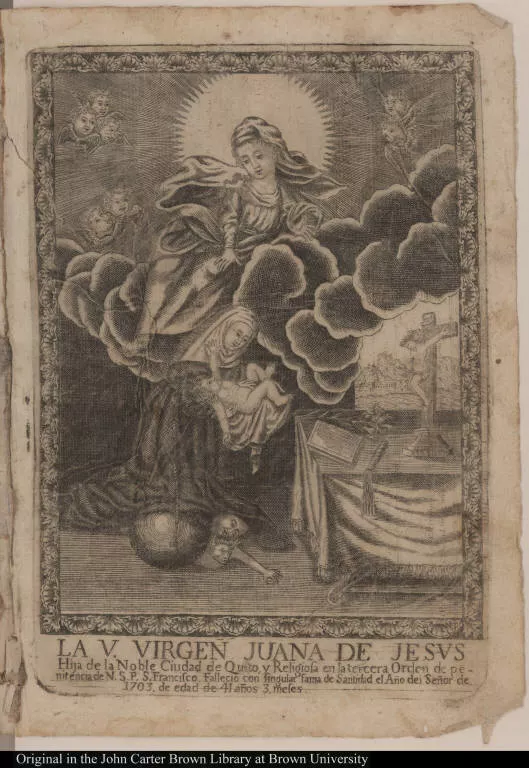

La V. Virgen Juana de Jesus Hija de la Noble Ciudad de Quito ...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Like many of the women featured in the present exhibition, Juana de Jesús (1662-1703) experienced ecstatic visions in which she embraced, mothered, and tended to the Christ child. In Juana’s case, these miracles had particular resonance because she first entered Quito’s convent of Poor Clares as an abandoned infant. Juana eventually became a lay sister in that same convent, and she cared for an orphaned toddler inside her cell. She supposedly used the sacred paintings and sculptures that adorned the convent to instruct the boy in the faith and drew inspiration from the purity and simplicity of his devotion. For Juana, as for many religious women at the time, love of the infant Christ and affection for real children thus became deeply intertwined.

5. Wealth and Rank

Obras del ilustrissimo, excelentissimo, y venerable siervo de Dios don J...

1762

-

p. 179

p. 179The lavishness of this engraving, and of the tome in which it appears, is appropriate to its exalted subject. Margarita de la Cruz (1567-1633) was a daughter of the Emperor Maximilian II and his Spanish wife, the Empress María. As a teenager, Margarita outraged Spanish court officials by refusing to marry her aging uncle, King Philip II, and instead taking vows as a Poor Clare. She spent the rest of her life in Madrid’s Descalzas Reales, a convent of women from the royal family and upper nobility. In the image shown here, Margarita stands between allegorical figures of Poverty (on the left) and Prayer (on the right). Beneath Poverty are crowns, coins, and other riches: illustrations of the worldly goods that Margarita renounced upon entering the convent.

The Vida of Margarita shown here is included in the Obras of Juan de Palafox y Mendoza (a man whose titles included Bishop of Puebla de los Ángeles, Mexico, and Viceroy of Mexico), but its authorship remains a subject of debate. When the text was first published in 1636, its author was listed as Margarita’s confessor, the royal preacher Juan de Palma, from whom King Philip IV had commissioned the work. Nevertheless, the editor of the Obras, Palafox’s nephew, contended that his uncle had written the Vida based on “materials and information” supplied by Palma, and the future bishop may well have been called upon to burnish the confessor’s prose.

6. Nourishing Body and Soul

Perfecta religiosa

1662

-

p. 595

p. 595The inscription shown here, written in a seventeenth-century hand, indicates that the book was to be read aloud in convent refectories and rooms designated for chores: “This book by Father Letona is appropriate for reading in the refectory and in the work room because all of it deals with our religious state. God grant that you enjoy it. Fare you well.” While eating or doing handiwork, nuns (and, for that matter, men in religious orders) listened to pious readings, which were meant to remind them never to lose sight of God as they nourished their bodies or engaged in the daily labors associated with convent life.

The Perfecta religiosa described in this book is Gerónima de la Asunción (1555-1631), also the subject of the Exemplo de todas las virtudes featured in the present exhibition. Letona constructed Jerónima as a pious exemplar who demonstrated her holiness by punishing her body with unusual rigor. According to Letona, Gerónima would “sometimes enter the refectory” wearing a crown of thorns, her head covered in blood, and then, in front of the entire room, “give her face three hard slaps.” Whether horrified or inspired, the nuns who heard these words read aloud as they ate their communal meals surely turned their thoughts from the worldly pleasures of food to the mortification of the flesh.

Arte de cocina, pasteleria, vizcocheria, y conserveria

1778

-

p. 5

p. 5Written by a chef to three Spanish kings and first published in 1611, this cookbook provides a window onto the culinary world of early modern nuns. The author, Francisco Martínez Montiño, details the preparation not only of elaborate banquets like those he served at the Madrid court, but also the kinds of sweet treats produced and sold by convents across Spain and its colonies: marzipan, sugary fritters, and almond and cherry tarts. Shedding light on the renown of convent baking, Martínez Montiño singles out nuns’ technique, claiming that a big, broad-handled spoon is required for those who want to “beat [their] batter with two hands, as nuns do.”

Credits

Editorial Notes: Items Pending Integration

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library