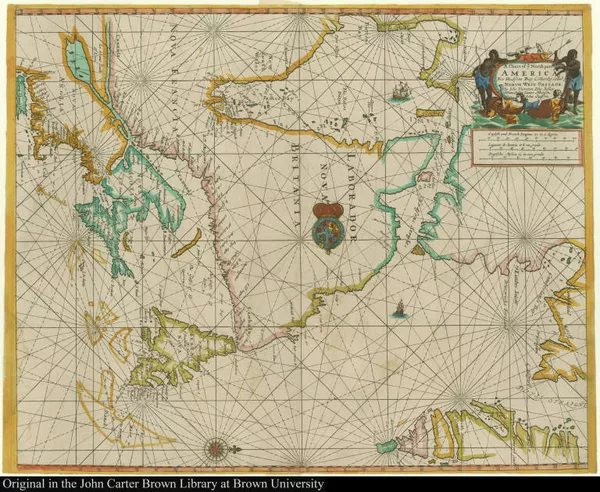

French writers on American waters

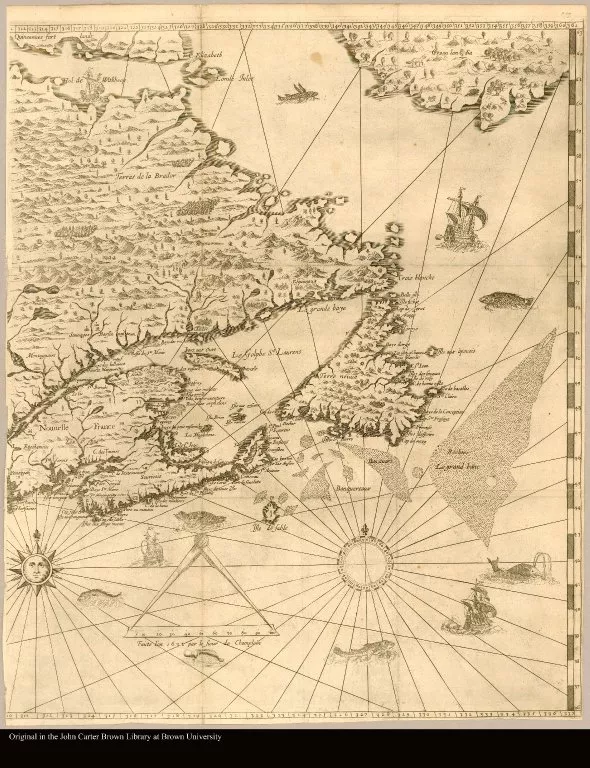

Samuel de Champlain

[Carte de la Nouvelle-France, augmentée depuis la derniere, servant à la...

1632

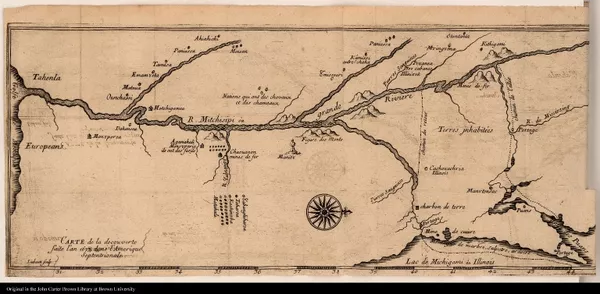

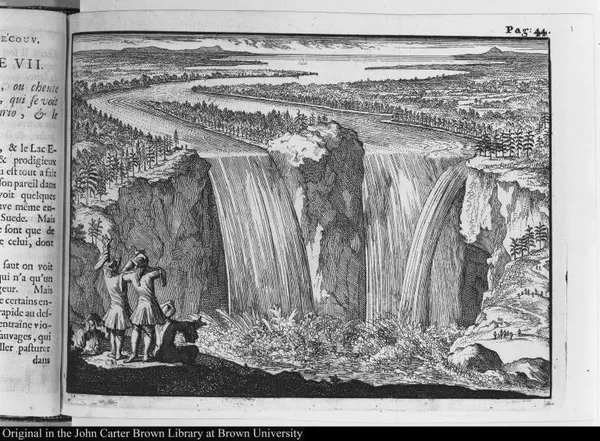

Claude Le Beau e.a.

Geschichte des Herrn C. Le Beau, Advocat im Parlament. Oder Merckwürdig...

1752

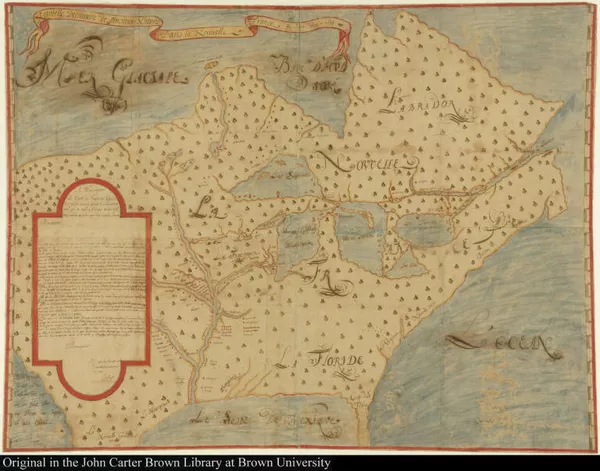

Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues e.a.

Brevis narratio eorum quae in Florida Americae provi[n]cia Gallis acciderunt

1591-1609

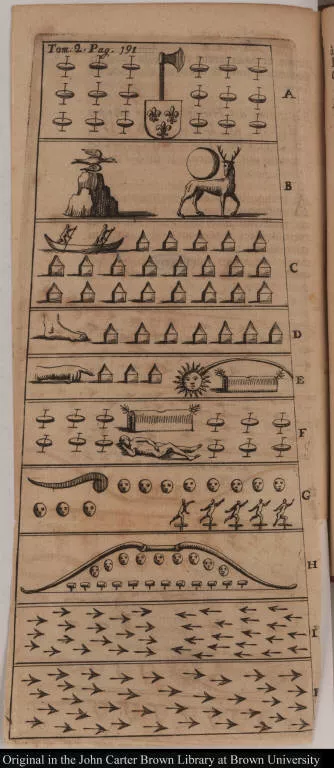

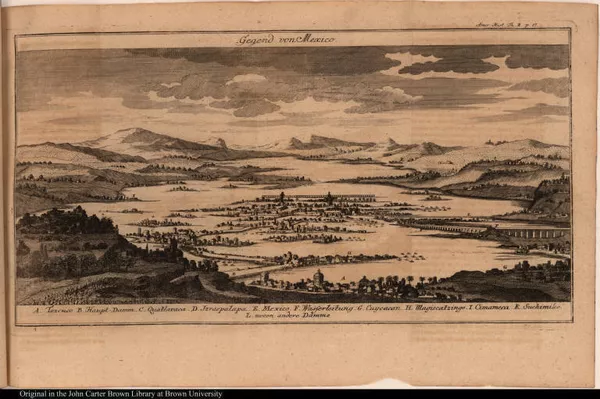

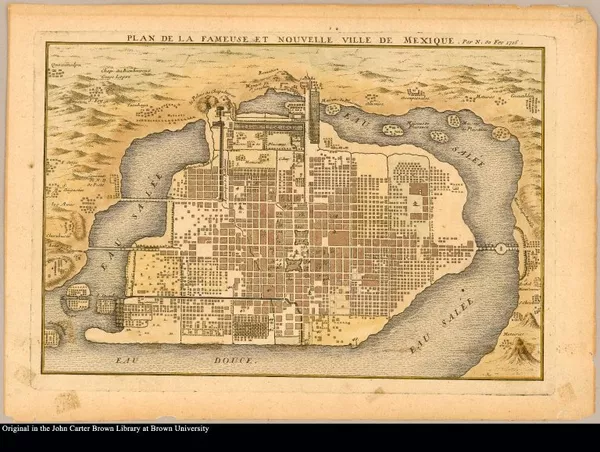

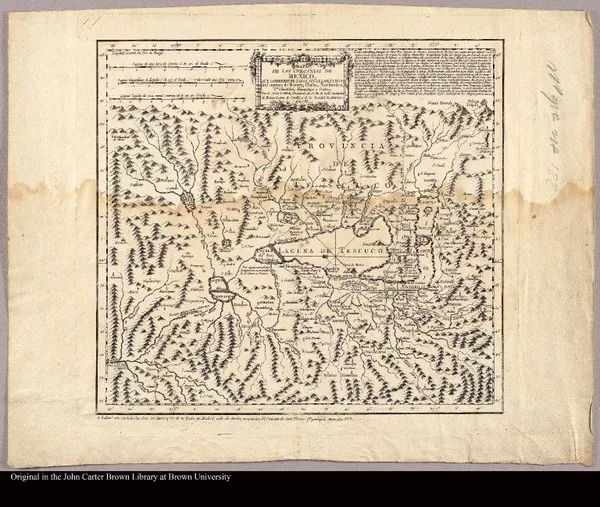

Gegend von Mexico.

1751-1800

Thinking through aquatic activity

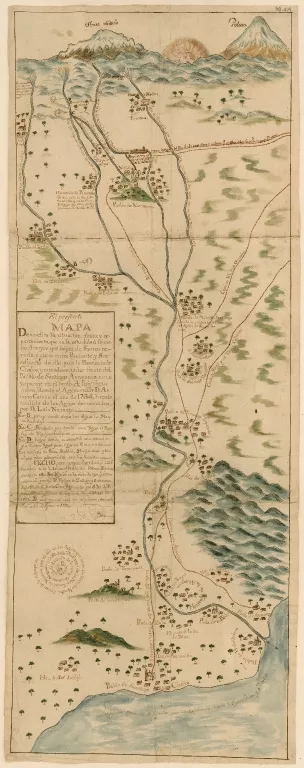

Controlling the waters of Tenochtitlan

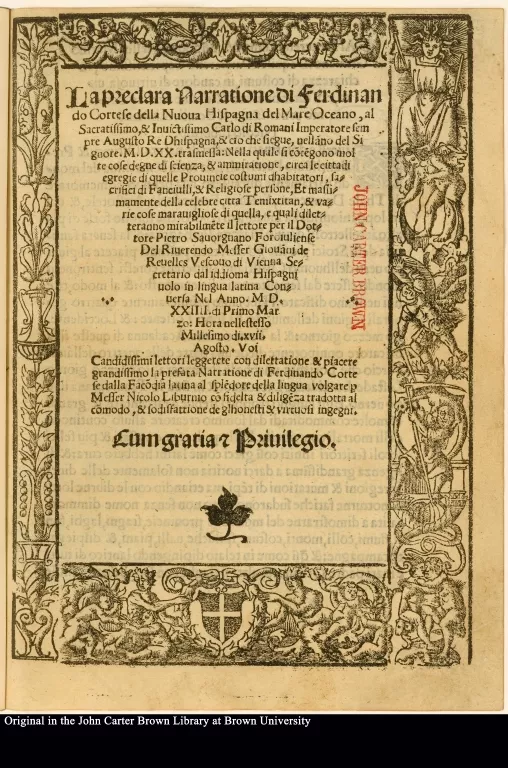

[Title page]

1492-1600

Joseph Francisco de Cuevas Aguirre y Espinosa e.a.

Extracto de los autos de diligencias, y reconocimientos de los rios, lag...

1748

Credits

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library