Intro

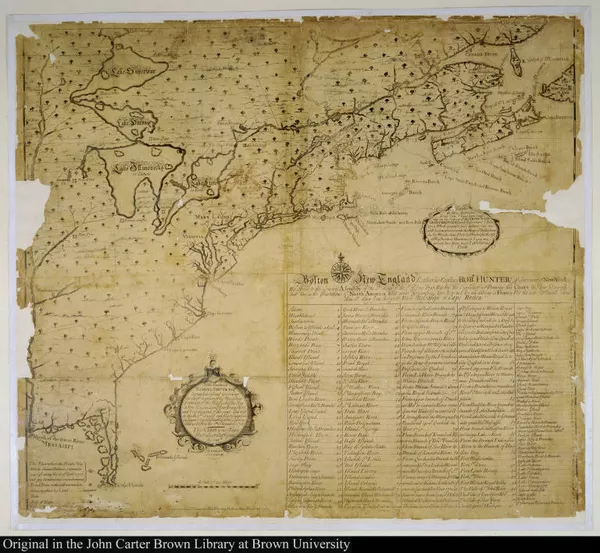

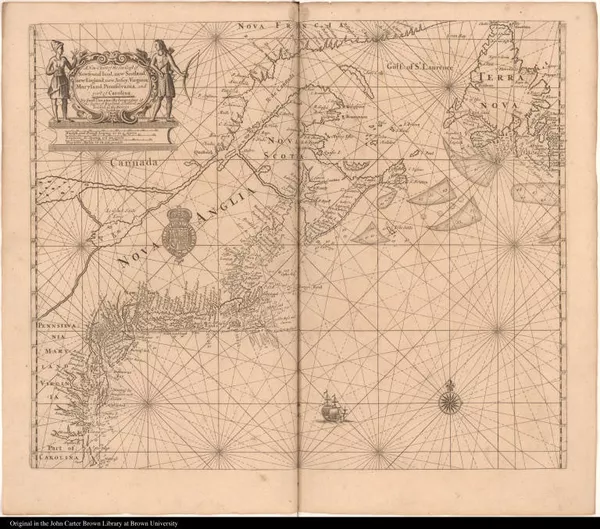

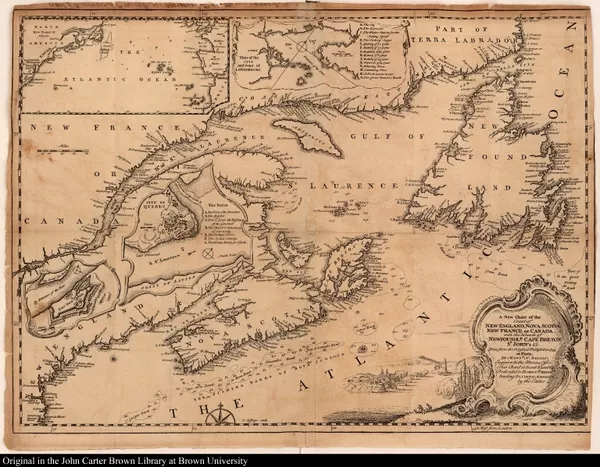

[A new chart of the English Empire in North America]

1717

-

p. 1

p. 1New England Warns of the French Threat

In this first copperplate map published in the British colonies, the New England view that the French were poised to push the New Englander's into sea makes it essentially a "war map." Southack take pains to point out (with crosses) the location of the French forts that surrounded the British colonies.

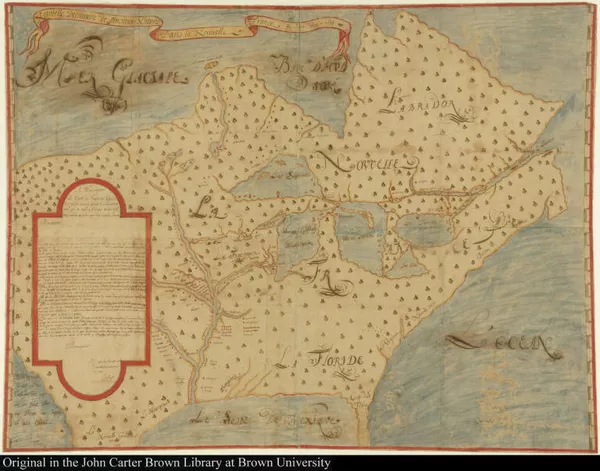

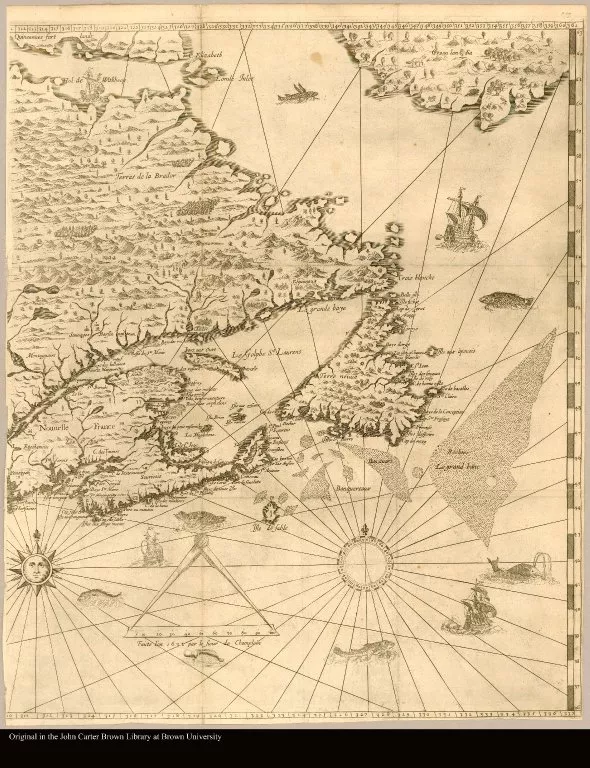

Nouvelle Decouverte de plusieurs Nations Dans la Nouvelle France en l'an...

1674

-

p. 1

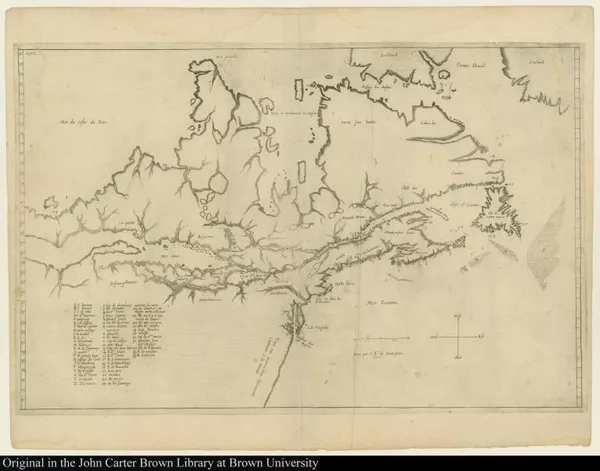

p. 1Knowledge and Possession

In 1673 the French fur trader Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit missionary, explored the Mississippi River, but records they kept of their trip were lost in a canoe accident. Upon his return to Quebec, Jolliet drew a map from memory, and the manuscript shown here—one of the earliest representations of the course of the Mississippi—is one of several copies that were made at the time. Away from the areas the French party actually traversed, the geography is fairly poor, but the map accurately shows the location of various Indian nations, information of vital interest to French traders and missionaries.

The cartouche at the left is a copy of a letter to the Governor of New France, Count Frontenac, in which Jolliet alludes to the fertility of the country and also to a (non-existent) water passage that would connect the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. With this kind of information about the interior readily available to the French, New Englanders' concerns were certainly realistic.

1. The Early French Exploration and Settlement: Inventing New France

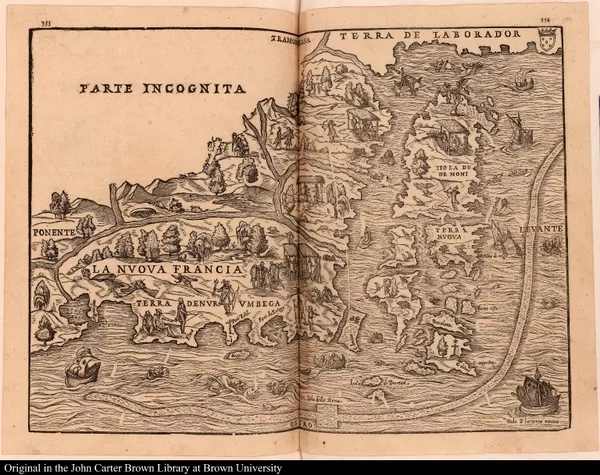

La Nuova Francia

1606

-

p. 1

p. 1This is the first printed map to focus on New England and New France. The geographic information is based on the 1524 voyage of Giovanni Verrazzano, who explored the American coastline for King Francis I of France. His avoidance of the dangerous coastline and shoals from Cape Cod to Maine created the "information gap" that gives this map its confused, foreshortened look.

Nonetheless, it clearly states French claims to the St. Lawrence region and emphasizes French fishing activity in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. Although Ramusio discusses the explorations of Jacques Cartier in his book, no Cartier information shows on this map.

1.1. Jacques Cartier and "Canadian Diamonds"

Discours du voyage fait par le Capitaine Iaques Cartier aux terres-Neufu...

1598

-

p. 5

p. 5Interest Rekindled

Because Cartier's explorations had not been financially successful there was no rush to publicize his efforts. But with the passing of fifty years and more, times had changed—France and Spain were at peace and a new king was on the throne (the Huguenot Henri IV, the first of the Bourbons) who encouraged the development through monopolies of mercantile interests such as the fur trade. The account of Cartier's expedition, which had first appeared in Italian in Ramusio's collection of voyages, the Navigationi et viaggi, was translated into French and published in Rouen in 1598. Its publisher expressed the hope that the account would serve as encouragement for a Canadian expedition by the Marquis de la Roche that year.

A shorte and briefe narration of the two nauigations and discoueries to ...

1580

-

p. 1

p. 1In 1580, almost 20 years before the publication of Cartier's account in France, John Florio translated Ramusio's Italian narrative into English and had it published in London as part of an effort to stir up sluggish British interest in overseas exploration and trade. By the turn of the century, the English were looking seriously at the advantages North America had to offer, interest that would eventually lead to colonization in New England and ever-escalating conflict with French interests to the north.

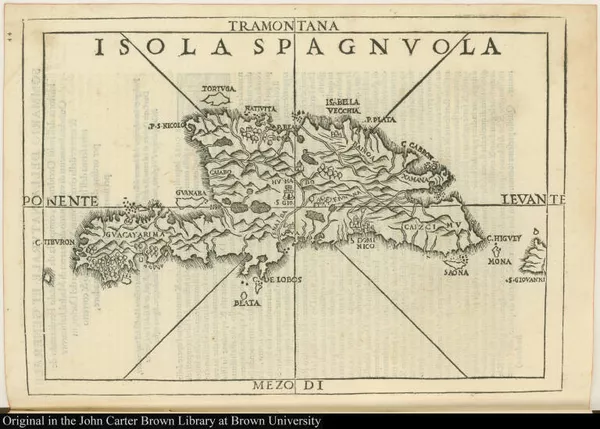

Isola spagnvola

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1Native American Custom?

At the bottom left center of this plan Cartier and his men greet the inhabitants of the Native American town of Hochelaga, near the site of present-day Montreal. Further to the left, two Native Americans carry Europeans "piggyback" fashion. Scholars have suggested that this was perhaps a ceremonial gesture of deference practiced by some tribes in the Americas. Many Europeans did not understand the subtleties of the ritual and expected to be carried everywhere.

Histoire de la Nouvelle France

1609

-

p. 57

p. 57"We do not live by mines"

Marc Lescarbot was a lawyer who spent a year in Canada, accompanying Samuel de Champlain in his explorations up the St. Lawrence River in 1608. He painted a glowing picture of the potential of the country and scolded Frenchmen for distracting themselves with religious discord and fruitless searches for imaginary golden cities, when they could instead be reaping the benefits of the fertility and the vast resources of New France.

Lescarbot's was the first detailed map of Canada published prior to the extensive exploration and mapping of the country by Champlain. The map locates the first trading post at Tadoussac (1600) and the Indian town of Hochelaga. "Kebec" is shown on a map for the first time, here in its Micmac form meaning "narrows of the river." The map also reflects the extensive French activity in Acadia (Nova Scotia and northern Maine), areas soon to be contested with Great Britain.

2. Samuel de Champlain: Father of New France

Brief discours des choses plus remarquables

1635

-

p. 1

p. 1Before New France: Champlain in the West Indies

The "Brief narrative" describes a voyage made by Samuel de Champlain to the Spanish West Indies from 1599-1601, two years before he first set foot in New France. Champlain made the trip as commander of his uncle's ship, which had been leased to the king of Spain for the yearly voyage to the "Indies." As the explorer explains in his introduction, this fulfilled a longstanding desire of his to see a world of things that Spain had kept hidden from prying French eyes and that he intended "to make a true report of them to his Majesty on his return [to France]." There has been considerable scholarly debate as to whether the manuscript "report" shown here is in the actual hand of Champlain, or whether it is a copy made by someone else. The final word on the matter has not yet been spoken (or written), but it is certain that this artistic rendering of landscape, flora and fauna, and the words that describe them is a valuable early view of America.

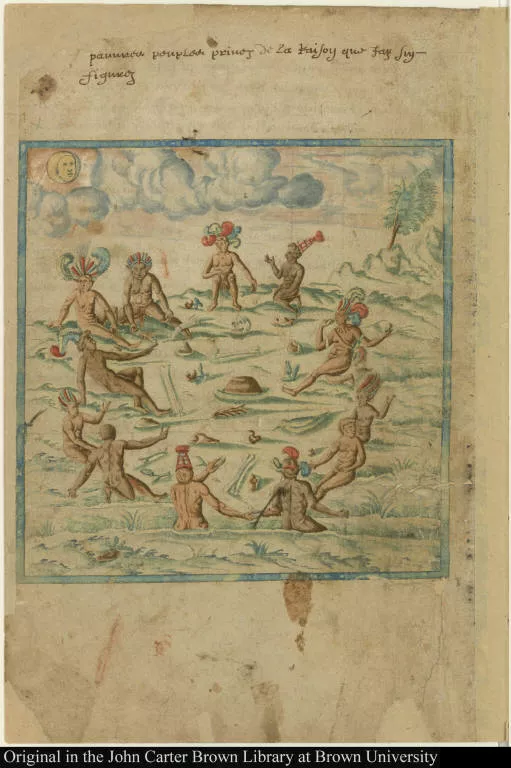

[Native American religious practices]

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1The aforesaid island of Santo Domingo is large, being one hundred and fifty leagues long, and sixty broad, very fertile in fruits and abounding in cattle and good merchandise, such as sugar, cassia, ginger, molasses, cotton, ox hides, and some furs. There are numerous good harbors and good anchorages, and only a single town, named Hispaniola [Santo Domingo], inhabited by Spaniards; the rest of the population are Indians, a good-natured people, and very friendly to the French nation, with whom they traffic as often as they can, but this is without the knowledge of the Spaniards.

[Native American religious practices]

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1This country is rather hot, and pretty mountainous; there are no mines of gold or silver, but only of copper.

[Native American religious practices]

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1At the commencement of his conquests, [the king of Spain] had established the Inquisition among them, and enslaved them or put them cruelly to death in such numbers, that the mere account of it arouses compassion for them. Such evil treatment was the reason that the poor Indians … fled to the mountains in desperation, and as many Spaniards as they caught they ate.

[Native American religious practices]

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1In the said country a great quantity of cochineal is gathered, which grows in fields as peas do on this side of the ocean, and it comes from a fruit the size of a walnut which is full of seed within.

The belief that cochineal (a red dye) was the seed of a plant was prevalent for a long time after the conquest of Mexico. Cochineal is actually an insect that feeds on the nopal cactus, whose dried and crushed bodies produce a high-quality red dye.

2.1. Champlain's First Observations of Canada

Des sauuages, ou, Voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouage, fait en la Fra...

1603

-

p. 7

p. 7When he returned to France in the fall, Champlain reported his observations on Canada and its peoples to the king, and presented them to the public in his first printed book, Des sauvages, shown here. One concession he made to the public taste for the exotic was his account of the Micmac legend of the gougou, a female beast of enormous size who ate men.

2.2. What did Champlain Look Like? And What did Champlain See?

Carte geographiqve de la Novvelle Franse / faictte par le sievr de Champ...

-

p. 1

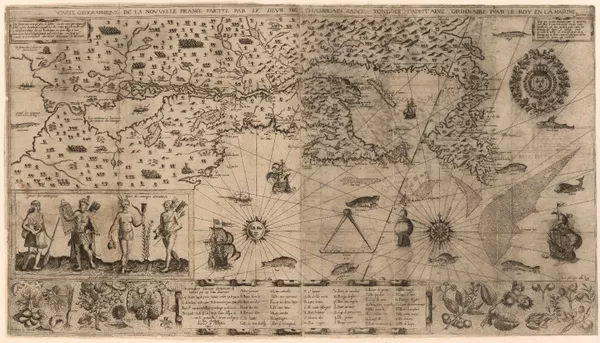

p. 1Champlain in the sun?

Marcel Trudeau, one of the most important historians of New France, believed the face in the compass rose on the 1613 Champlain maps could represent Champlain's face, based on the supposition that cartographers of that age traditionally portrayed themselves in their works.

-

p. 1

p. 1Champlain the Cartographer

Samuel de Champlain was the first truly scientific cartographer in North America and this remarkable map is the first to record personal, on-site observations of the variation of the compass. The top of the map represents magnetic north while the slanting latitude bar on the right indicates true north.

-

p. 1

p. 1Shown for the first time on this map are indications of the location of the Great Lakes...

-

p. 1

p. 1Lake Champlain...

-

p. 1

p. 1... and the outpost of Montreal.

-

p. 1

p. 1The map is decorated with the explorer’s careful depictions of Native American peoples and plants. It is truly a masterpiece.

Les voyages du sieur de Champlain Xaintongeois, capitaine ordinaire pour...

1613

-

p. 275

p. 275This image of a European soldier valiantly firing against a throng of native Americans is a self-portrait originally sketched by Champlain.

-

p. 151

p. 151Here Champlain is shown warning Jean de Biencourt, sieur de Poutrincourt, one of the leaders of the first Acadian settlement.

-

p. 151

p. 151In the summers of 1605 and 1606 Champlain made reconnaissance voyages along the North American coast to assess the potential for trade and settlement farther south, reaching his farthest-south point at Nauset on Cape Cod in the summer of 1606. The chart shown here of "Beau Port," modern-day Gloucester, Massachusetts, is considered the best of the Champlain charts. In Champlain's words, Gloucester was rejected as a settlement site because of “the duplicity of the large native population.” Native American distrust of Champlain's party was, no doubt, a direct result of a century of confrontations with European fishermen and traders who made annual visits to the fishing banks in the summer season. It was also recognized early on that the New England climate would not produce the prime cold-climate furs desired by French fur traders.

-

p. 217

p. 217Site of Quebec

-

p. 229

p. 229Champlain's habitation at Quebec.

[La Nouvelle France]

1616

-

p. 1

p. 1Champlain's Explorations, 1615-1618

Champlain’s Voyages of 1619, to the right, carries his story to 1618, with its recounting of arduous exploration, unsuccessful battles against Native Americans, life-threatening wounds, and constant frustration. The map shown here is something of a puzzle. Its geographical and ethnographical information mesh with the narrative account of Champlain’s explorations of 1615-1618, which would suggest that the map was drawn by Champlain to illustrate Les voyages of 1619. However, no copy of the book contains the map. In fact, no evidence has been unearthed to explain why the map was not issued with the book as published.

2.3. Quebec Surrenders to the English. Champlain Sent Home.

Articles accordez par le roy. a la Compagnie de la Nouuelle France

1628

-

p. 1

p. 1Development Plan for New France

While Champlain was contending with Kirke’s attack in Quebec, attempts were underway back in France to find the means to support the struggling North American colony that was barely able to keep itself going. New France seemed unable to attract positive notice at home. Certainly, the perception of severe weather was a huge image problem, but Canada suffered from a chronic lack of population primarily because the fur monopolists were content with the status quo and not interested in supporting efforts to settle colonists in the territory. The charter shown here was granted by Louis XII to the Company of the Hundred Associates, who were charged with developing Canadian settlements.

Au roy

1630

-

p. 9

p. 9A Plea for Support

When Champlain returned to Paris in 1629, negotiations for the restoration of Canada were already in process and he joined in the effort. The veteran explorer addressed the king directly in this memoir, listing his many services to France and his long residence in Canada, vowing himself after thirty years still resolute, eager to convert the heathen, and determined to discover a western passage to the South Sea (the constant dream of 16th and 17th-century European explorers). For good measure he provided a detailed description of the natural resources that could be developed effortlessly for the glory of France. This is perhaps the rarest of Champlain's published writings.

Traicté entre le Roy Louis XIII. et Charles Roy de la Grand' Bretagne, ...

1632

-

p. 7

p. 7A Dowry Paid, New France Restored

Shown here is the treaty that restored New France to France. French success was finally achieved by the discharge of an old debt—Louis XIII paid his sister Henrietta Maria's dowry, owed the English crown since she was married to Charles I of England in 1625.

[Carte de la Nouvelle-France, augmentée depuis la derniere, servant à la...

1632

-

p. 1

p. 1A Lifetime of Exploration

Champlain’s last map accompanies his most complete publication, which describes events in Nouvelle France from the beginning up to 1629. In the years since his last publication Champlain had not been occupied with personal exploration, but instead by lobbying and working for the good of the venture, mostly in France...

[Carte de la Nouvelle-France, augmentée depuis la derniere, servant à la...

1632

-

p. 1

p. 1A Lifetime of Exploration

... Banished from Quebec by the English in 1629, Champlain was finally able to return in 1633. He suffered a stroke in October, 1635, and died on Christmas Day. At the time of Champlain’s death Quebec had just 200 people, while the English colonies numbered many thousands.

3. Delenda est Canada! Canada must be Destroyed!

An encouragement to colonies

1624

-

p. 51

p. 51Contested Ground

King William's War was primarily a series of bloody French and Indian raids on the northern flanks of the British colonies in New York and New England, and both English and French settlers in the contested ground bore the brunt of organized military and guerilla actions...

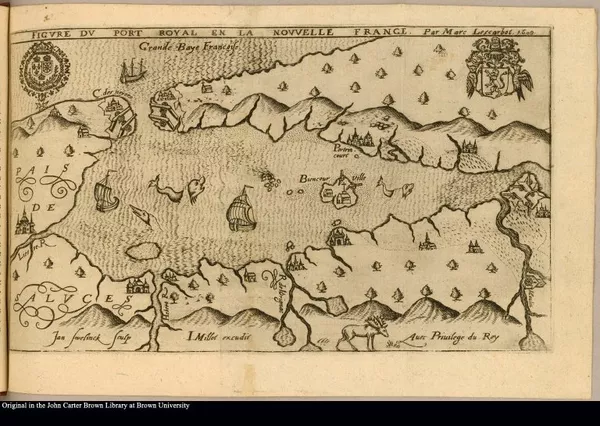

Figvre dv Port Royal en la Nouvvelle France

1618

-

p. 1

p. 1Contested Ground

.... A look at the two maps of the period shown here illustrates the overlapping territorial claims and assumptions that were to lead to prolonged hostilities between England and France until France decisively lost her territory in 1763.

A journal of the late actions of the French at Canada

1693

-

p. 1

p. 1Lachine, Canada, 1689 / Schenectady, New York, 1690

In the summer of 1689 news arrived at Albany that England and France were at war. Enthusiastically, the Iroquois allies of the English descended on Lachine, near Montreal, killing French settlers and destroying buildings, crops, and animals. The following winter of 1690 the French returned the favor, employing those same Iroquois tactics in their attacks against the English settlements of Schenectady, Salmon Falls, Fort Loyal, and fortified Mohawk towns (called "castles" by the English) in the Albany area. Shown here is the official account of the attack on Schenectady by Nicholas Bayard, one of the English defenders.

Histoire de l'Amerique Septentrionale

1722

-

p. 84

p. 84Instilling Fear

Many of the French raids on English northern frontier settlements were made by French Canadian coureurs du bois and by French soldiers camouflaged in Indian dress and war paint. The idea that white men (even Catholic white men) would attack and scalp "their own kind" was particularly horrifying to English settlers alone on the frontier.

3.1. The "Religion Card"

Memoirs of odd adventures, strange deliverances, &c. in the captivity of...

1736

-

p. 1

p. 1Pemiquid, Maine, 1689

We had some that we took inform us, that if we had come but four days sooner, they had not above 600 men in town, but being so long in the river before we got up, they had notice of us, and had sent for all their strength thither, so that there was now in the town 3,000 men and eight hundred that were near us in swamps and woods, to keep us constantly alarmed.

Pemaquid, the most outlying settlement of the English on the coast of Maine, surrendered to a force of French and Maliseet Indians in 1689. John Gyles, then age nine, was abducted along with his mother and siblings and taken north to Canada. He was terrified of "Jesuits," and when a French missionary offered him a biscuit to eat he buried it–although he was very hungry–for fear that it contained some kind of magic that would make him "love" the enemy. Gyles spent six years with the Indians and three years with a French master. When finally released he spoke English, French, Maliseet, and Micmac, and was in demand as an interpreter for peace negotiations and prisoner exchanges.

An account of the late action of the New-Englanders, under the command o...

1691

-

p. 1

p. 1The Phips Expedition, the "Glorious Enterprise" of 1690

In October, 1690, the French turned back an attack on Quebec by a naval force led by Massachusetts governor, Sir William Phips, who was riding a wave of enthusiasm following his capture of Port Royal, Nova Scotia, the previous spring. But the outcome this time was far different. Because of a lack of competent pilots with knowledge of the St. Lawrence River, the fleet took nine weeks to reach Quebec and hope of any measure of surprise faded. In addition, many of the troops were sick with small pox, and only 1,200 of the original 2,000 were able to land. Thomas Savage, the author of this account, was a part of the expedition.

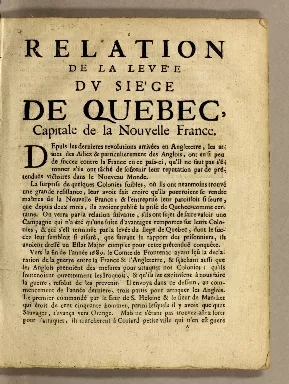

Relation de la levée du siège de Quebec, capitale de la Nouvelle France

1691

-

p. 1

p. 1Celebration of French Victory

On the other side, the inhabitants of Quebec rejoiced, and it was noted with satisfaction that what the English had bragged would be an easy victory did not come to pass.

4. War of the Spanish Succession, Queen Anne's War and the "Great Design"

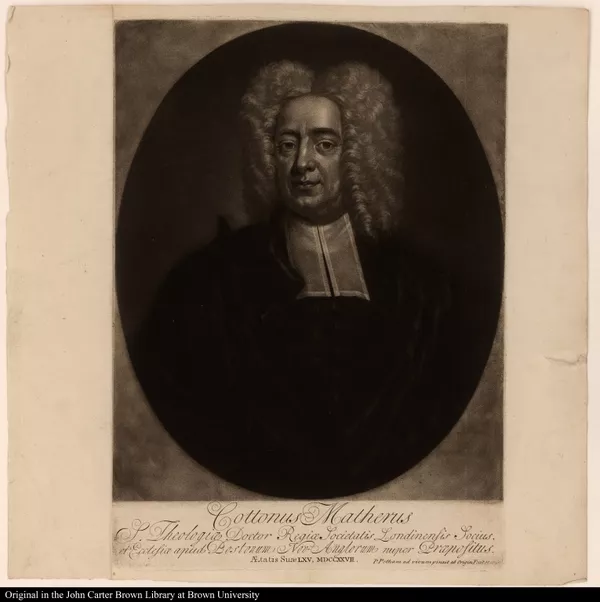

Cottonus Matherus S. Theologiae Doctor Regiae Societatis Londinensis Soc...

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Victory Will Come

Like Israel engaging against Benjamin, it may be we saw yet but the beginning of the matter; and that the way to Canada now being learnt, the foundation of a victory over it might be laid in what had already been done.nce.

The Phips expedition of 1690 was the first substantial New England operation against Canada, and although it failed, many, like Cotton Mather, perceived that it would lead to future success because the troops had been able, without any interference from the enemy, to reach the ramparts of Quebec.

The deplorable state of New-England

1708

-

p. 1

p. 1New England Humiliated at Port Royal, 1707

The years following the defeat of the Phips expedition saw an escalation of New England interest in mounting another attack on the French in Nova Scotia and Quebec, which was fueled by continuing French and Indian attacks on English frontier settlements. In 1707 Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island provided about 1,000 men and twenty-five vessels for an expedition to attack Port Royal in Acadia. Although the French garrison had fewer men, it held off the attackers until reinforcements arrived and New England experienced defeat once again. Angry voices, such as Cotton Mather's, (whose ability to craft a title is truly impressive) were raised in condemnation of the perceived mismanagement of the expedition.

Relation du voyage du Port Royal de l'Acadie, ou de la Nouvelle France

1708

-

p. 1

p. 1French Victory at Port Royal, 1707

This addendum to Diereville’s account reprints a news sheet item of February 25, 1708, celebrating the Acadian’s victory over New England forces.

Duodecennium luctuosum

1714

-

p. 5

p. 5Mather's Lament for the Abducted

"To think of it; that we should still have some scores of our people, enchanted and enslaved, in the idolatries of Canada, and so held in chains of darkness by the frauds, and cheats, and chicaneries of the French priests."

A New Chart of the Sea Coast of Newfound land, new Scotland, new England...

1706

-

p. 1

p. 1Expedition in Disarray

Adding to the problems caused by fog and a lack of pilots experienced in St. Lawrence River navigation, there was also the issue of inadequate cartographic information. The chart of the St. Lawrence shown here is an example of what was available to British seamen at the time. It is plain that the lack of specific information about soundings and currents and the small scale and general nature of the chart made it especially important to have knowledgeable pilots to guide the fleet.

A letter to a noble lord, concerning the late expedition to Canada

1712

-

p. 1

p. 1Picking up the Pieces

The situation of that country gives the people an opportunity to invade all the British colonies when-ever they please. … And as the French are on the back of us, so the Indians are behind them, who with their united force often fall upon the English, and may be able in time (if not extirpated) to drive 'em into the sea.

The 1711 British naval expedition against Quebec has been considered one of the most inglorious operations in British military annals. It ended Admiral Hovenden Walker's naval career and gave rise to spirited debate. Here, Jeremiah Dummer sets out to answer two recurring questions about the debacle. First, would the campaign have been worth the effort and expense even if it had been successful (he says yes); and, second, where should the blame be laid for its failure. In reply to this last question Dummer found it necessary to answer the charge that the failure was New England's fault. Rumor had it that there had been notable and criminal lack of enthusiasm for the venture among Boston merchants who profited from trade with the enemy and dragged their feet in gathering provisions for the troops.

4.1. The Four Indian Kings

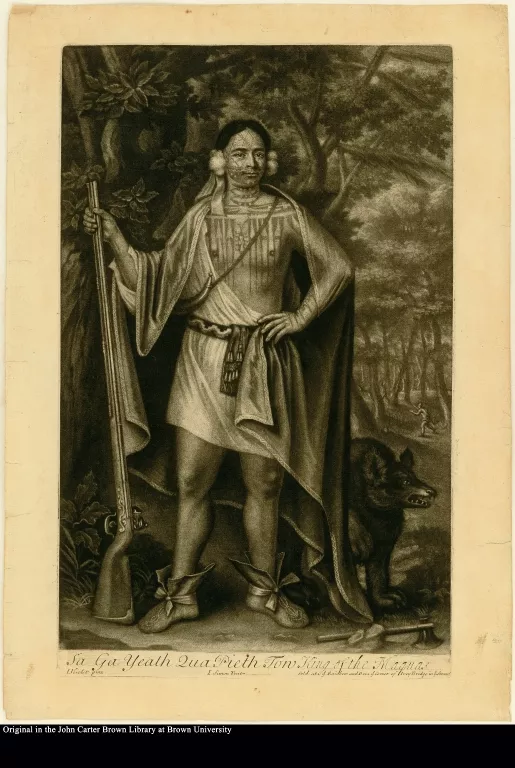

Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Ton King of the Maquas

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Sa Ga Yeath, also called Brant, was a pro-English Mohawk with no formal claim to a leadership position.

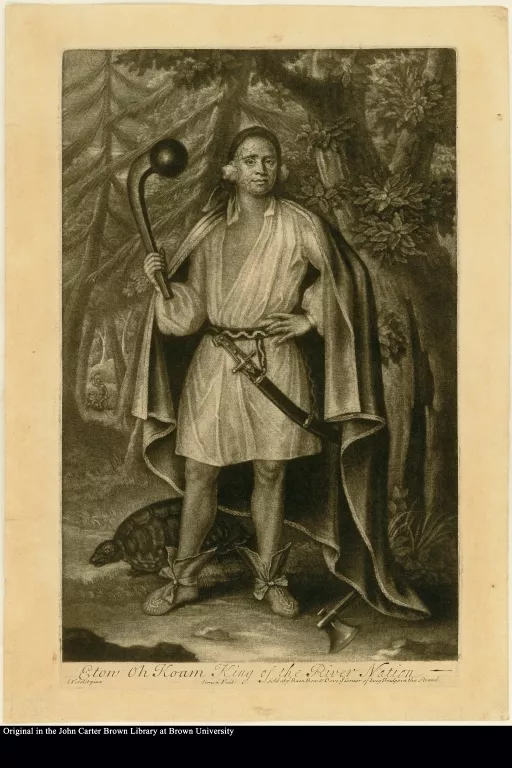

Etow Oh Koam King of the River Nation

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1One of the "kings," also called Nicholas, was not an Iroquois at all. The River Nation was another name for the Mahicans, who were under the influence of the Mohawks, but not part of the confederacy. Etow Oh Koam may have been important later, but in 1710 was without status.

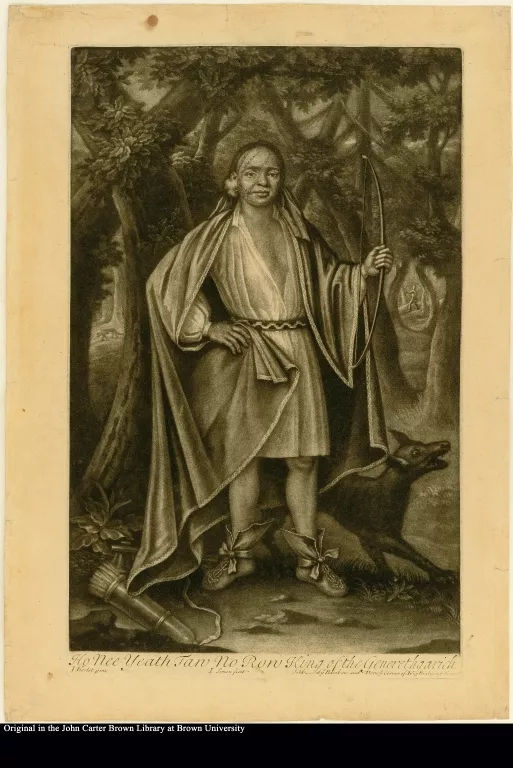

Ho Nee Yeath Tan No Ron King of the Generethgarich

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Ho Nee Yeath, also called John, was another pro-English Mohawk with no formal claim to leadership status.

"Generethgarich" is apparently a reference to Canajoharie, a western Mohawk town in what is now New York State.

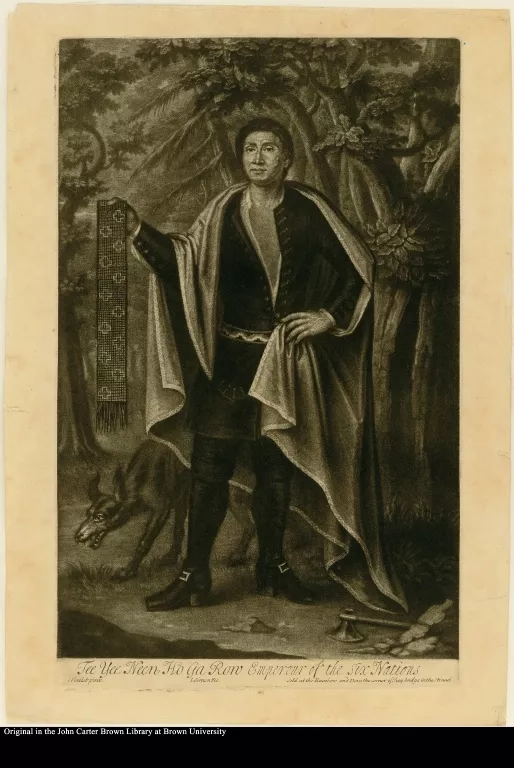

Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row, Emperour of the Six Nations

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Only one of the "kings" could possibly be described as a sachem, and that would be a stretch. Theyanoguin, whose Christian name was Hendrick, belonged to the council of the Mohawk tribe, but not to that of the Iroquois confederacy as a whole. Even among the Mohawks he was still, at the age of thirty, a minor figure and hardly an "Emperor."

The brave old Hendrick the great Sachem or Chief of the Mohawk Indians, ...

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1The identity of the man in this engraving is disputed. A Mohawk named Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row, also called King Hendrick, was presented to Queen Anne in 1710 as one of the so-called "Four Indian Kings" who traveled to London on a diplomatic mission.

The common story has been that in 1744 he returned to England for an audience with King George II, at which time he had his portrait painted. The historian Alden Vaughan, however, argues that the engraving shown here was of different individual—Hendrick Theyanoguin—a Mohawk known for his activities during the Indian wars of the 1740s, for his speech to the Albany Congress of 1754, and for his death at the battle of Lake George in 1755.

Vaughan believes that this man never traveled to England and the portrait (now lost) upon which the engraving was based was painted by an itinerant English or American artist in America.

5. The War of the Austrian Succession, 1740-1748

A View of the Landing the New England Forces in ye Expedition against Ca...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1New England's Success Against Louisbourg

The provincial force that successfully attacked Louisbourg was a cross-section of nonprofessional soldiers and inexperienced volunteers with little conception of discipline. Overall command of the invasion force was given to General William Pepperrell of Maine and from the start there was a harmony between the soldiers and the officers that was a credit to the leaders of the expedition.

Massachusetts and the District of Maine raised 3,250 men, Connecticut 500, New Hampshire 450, while New York sent guns, and Pennsylvania and New Jersey sent money (Rhode Island sent some men as well, but they were late in arriving). The provincial fleet included transport ships and armed vessels with 240 guns; it was supplemented at Canso by a small British squadron of 10 warships and 500 guns.

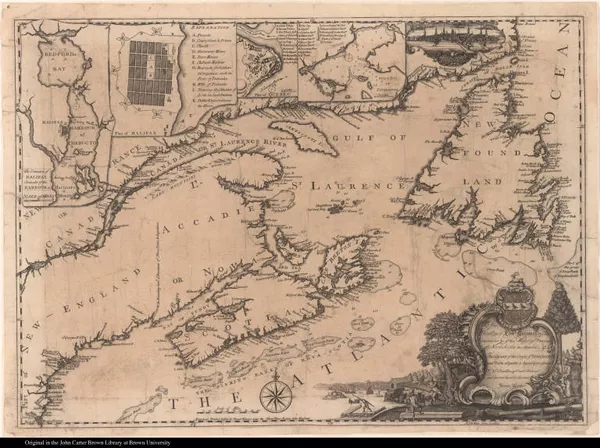

A New Chart of the Coast of New England, Nova Scotia, New France or Cana...

1746

-

p. 1

p. 1Victory Celebration

A celebratory dedication and explanatory cartography mark the victory of the New Englanders at Louisbourg. The map itself has a great deal to say—it situates the French fortress on the North Atlantic coast, provides close-up plans of Louisbourg and Quebec and, next to the title cartouche at the lower right, shows the siege in progress.

To the Hon. Wm. Shirley, Esq; Governor and Captain-General of Massachusetts Bay, Who projected; To Sir Wm. Pepperell, Knt. General, Who commanded; To Peter Warren, Esq; Admiral, Who assisted in; And to all the brave New-England People, Who served at,The enterprize against Cape Breton

Lettre d'un habitant de Louisbourg

1745

-

p. 1

p. 1The French Point of View

Highly critical of French colonial policy, this letter—the only unofficial account of the Louisbourg siege from the French standpoint—was written by an eyewitness to the action and was printed in Paris, not in Quebec as it states on the title page. The anonymous author says that one of the reasons for the French defeat was the low salaries paid to colonial officers, which made it necessary for them to engage in private trade, which in turn made them hold personal interest above national interest and led to distrust between the leaders and their troops.

An astronomical diary, or, An almanack for the year of our Lord Christ 1747

1746

-

p. 1

p. 1"Victory implor'd for success against the French in America." In: Nathaniel Ames, An astronomical diary … for the year of our Lord Christ 1747, Boston, 1746.

To his Excellency Edwd Cornwallis Esq; Governour &c of his Majestys Prov...

1750

-

p. 1

p. 1The Founding of Halifax

Canadian raids against frontier settlements in Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts actually increased after the fall of Louisbourg. In August, 1745, Fort Massachusetts was captured and its garrison taken captive to Canada. Saratoga, New York, was captured and destroyed that same November by a force of Canadians and Indians, and in the winter of 1746-47, a daring raid on Grand Pré, Nova Scotia, overwhelmed a surprised New England garrison. To combat this heightened French threat the British established Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1749. In 1750 James Turner, an English engraver newly arrived in the colonies, satisfied Bostonians' desire to keep up-to-date with unfolding events in the North by publishing this map, a visual handbook for the face-off between New England and New France. Note the cartouche at the lower right, which shows the building of Halifax. The view of Boston at the upper right recalls Thomas Johnston's view of Quebec.

5.1. The French and Indian War, 1755-1763

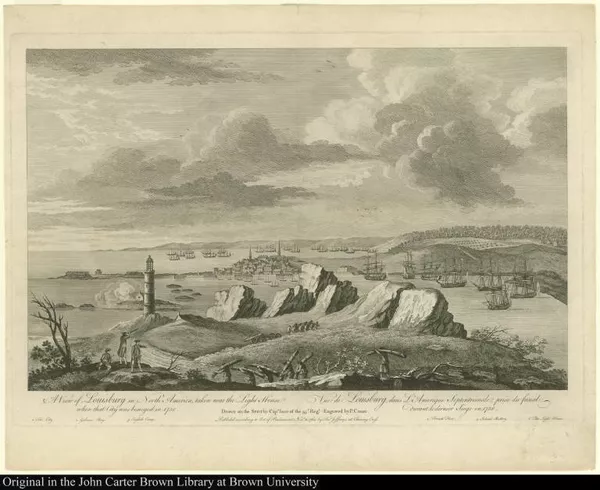

A View of Louisburg in North America, taken near the Light House when th...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Louisbourg Falls Again

The English expedition against Louisbourg in 1758 consisted of about 10,000 British troops, including colonials, under the command of Sir Jeffrey Amherst. The attack was fiercely resisted by the French, but English cannon doggedly pounded the fortress into rubble and the defenders were forced to surrender after eight weeks. This left the route to Quebec undefended, but it was too late in the season to mount an attack there. Instead, remembering Louisbourg's rise after its first defeat in 1745, the British spent their time leveling the fortress to eliminate any future threat.

By what I could learn when I was among them, they do not fear our numbers, because of our unhappy [internal] divisions, which they deride, and from them expect to conquer us entirely! which may a gracious God in mercy prevent!

A faithful narrative, of the many dangers and sufferings, as well as won...

1758

-

p. 9

p. 9Intelligence Gathering

Throughout the course of a century and a half of war and skirmish between the colonists of the northern British colonies and those of New France, numerous settlers and soldiers were captured and taken to Canada, often staying for years as servants or as adopted members of French or Indian families. Those who managed to escape or buy their way out of Canada often returned home and sold their stories, which were read by an eager audience who enjoyed "captivity" tales of all kinds. These stories also provided intelligence about the enemy in Canada—the society and customs of the inhabitants and the state of their defenses and fortifications.

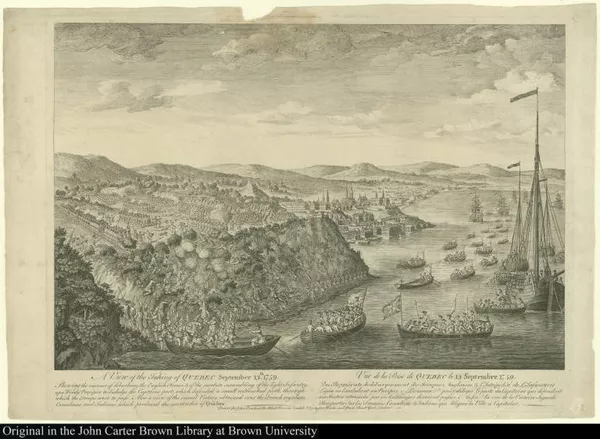

A View of the Taking of Quebec September 13th. 1759. Shewing the manner ...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1British and Colonial Forces Finally Take Quebec

In the fall of 1759 Sir Charles Saunders led a vast armada of warships and transports up the St. Lawrence for the siege of Quebec, impressive on its rocky 200-foot eminence commanding the river. At the same time, British General Wolfe landed his 9,000 troops (supplemented by American Rangers) on the Isle d'Orleans just below the city. The French tried, but failed, to dislodge the British fleet with fire ships, but Wolfe still had trouble making any headway. In a surprise night maneuver he led a landing party of 4,500 that scaled the heights of Quebec, where a short fight followed on the Plains of Abraham in which both Montcalm, commander of the French forces, and Wolfe were mortally wounded. Five days later, on September 18, Quebec surrendered. The British troops holed up in the city through the fierce winter, and in the spring faced another French army that had marched from Montreal to dislodge them. A bloody fight followed in which the English, outmanned and weakened by a winter of disease and privation seemed destined to lose, but the timely arrival of the British fleet allowed them to evacuate instead.

An astronomical diary

1759

-

p. 1

p. 1Quebec: A Celebration in Verse

"When proud Quebeck must fall"

The conquest of Quebec. A poem. By Joseph Hazard

1769

-

p. 5

p. 5Quebec: A Celebration in Verse

Joseph Hazard of Lincoln College and the Reverend Cooke, Fellow of New College and Chaplain to the Marquis of Tweedale, were two runners-up for the "conquest of Quebec" poetry prize offered by the Earl of Litchfield, Chancellor of the University of Oxford.

5.2. Canada Surrendered to the British

5.3. French Caricatures of Colonial Troops

6. The American Invasion of Canada, August 1775-October 1776

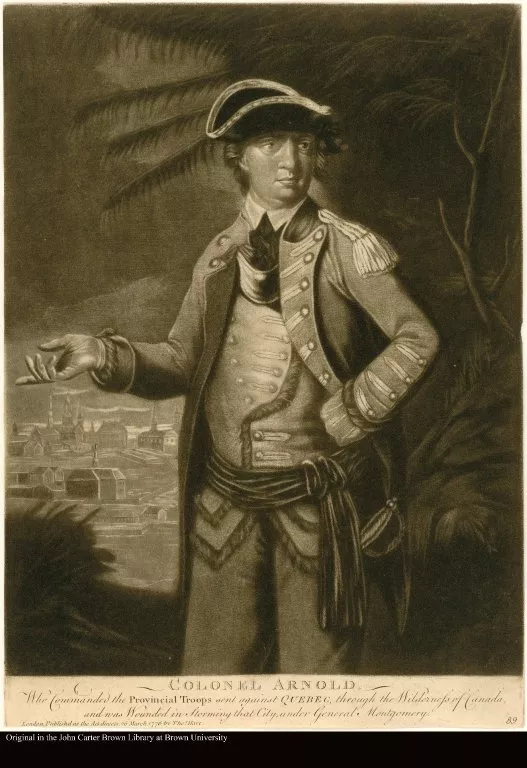

COLONEL ARNOLD. Who Commanded the Provincial Troops sent against QUEBEC,...

1776

-

p. 1

p. 1Benedict Arnold, Flawed Hero

Before Benedict Arnold turned traitor in 1780, he was widely considered one of the most up-and-coming young military leaders of the American Revolution. The two-pronged American offensive in Canada had been authorized by Washington, with one army traveling overland to attack Montreal while a secondary force of 1,000 navigated up the Maine river system to Quebec. Benedict Arnold was appointed to command the Maine contingent. Troops were sent from Boston to Newburyport, where river bateaux had been constructed to transport the soldiers the 320 miles to Quebec. The expedition left on September 19th, but since only green wood had been available for construction of the boats,few of the craft made it beyond the first third of the journey. The inexperienced troops, ill-prepared for the hardships, slogged on—a third turned back, a hundred died of exposure, and survivors were reduced to eating soap, shoe leather, and cartridge boxes. About 600 finally reached the St. Lawrence River on November 9th where they were joined by General Montgomery with 300 more men. The combined forces began the siege of Quebec on November 19th.

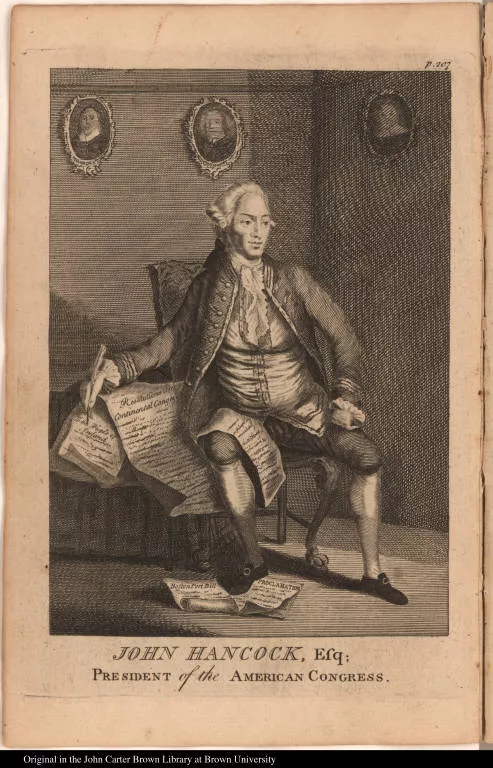

John Hancock, Esq; President of the American Congress.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1After the fermentation of party zeal has subsided, and men coolly consider the actions of others, and their principles, they will be obliged to confess, that the march of colonel Arnold and his troops is one of the greatest exploits recorded in the annals of nations, whether the way in which they marched, the season of the year, the severity of the climate, and the many other disadvantages and hardships which attended them are considered. They were only new soldiers, who had but hardly taken up arms for the defense of their liberties, and had never been accustomed to the hardships of war; they were led through a wilderness unexplored by human eye, where there were no paths, and through thickets almost impenetrable, and swamps next to impassible. They had no possibility of obtaining any more provisions than they carried with them, till they came to Canada, either by force or otherwise, and it was uncertain when they should arrive there.

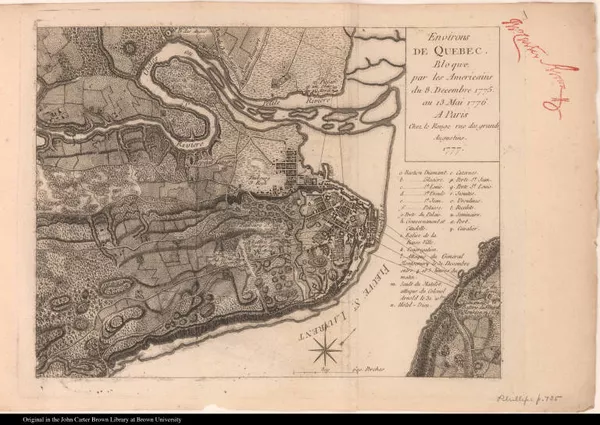

Environs de Quebec. Bloque par les Americains du 8. Decembre 1775. au 13...

1777

-

p. 1

p. 1Failed Assault

Invested in a siege that could last for months and faced with their troops' expiring enlistments on January 1, the American commanders arranged an attack on Quebec's formidable defenses for the early morning of December 31, 1775. The attack was quickly detected (Murray in his Impartial history, claimed they were given away by a traitor) and Montgomery and fifty others were killed. Arnold and thirty-six others were wounded and 387 Americans were taken prisoner. British losses were seven killed and eleven wounded. Direct attack had failed, but a siege dragged on throughout the winter. By spring it was obvious that the Americans could not take Quebec, and in May, when the British fleet sailed up the St. Lawrence toward the capital, the Americans fled after the battle of Three Rivers on June 8. This is a French copy of a British map published the previous year in London.

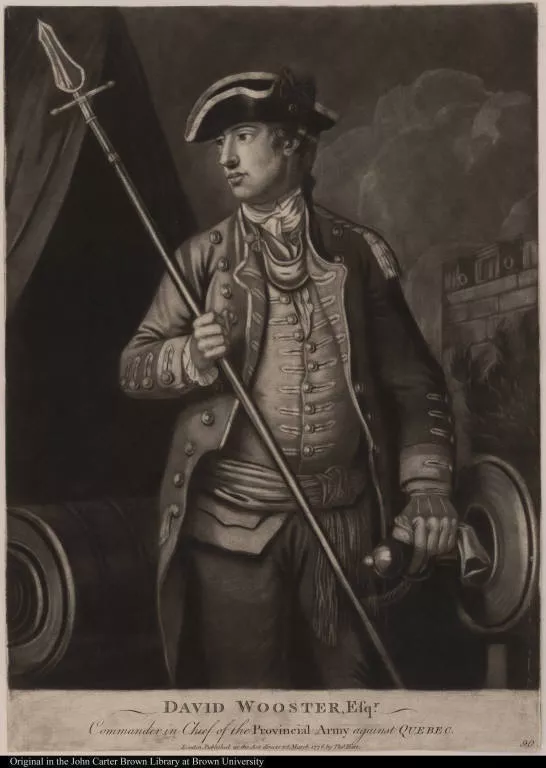

David Wooster, Esqr. Commander in Chief of the Provincial Army against Quebec.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1David Wooster, Flawed Leader

David Wooster was a seasoned soldier, having served Connecticut in several colonial wars. After the failed American assault on Quebec, during which Montgomery was killed, Wooster succeeded to the command, but his informality with the enlisted men undercut discipline, and his arbitrary, restrictive, and religiously biased actions towards the civilian population outraged Canadian Catholics. Petty jealousies led to quarrels with younger generals, including Benedict Arnold, and Wooster was replaced and shortly thereafter dismissed from the service as "totally unfit to command." Eventually, he was exonerated by a congressional investigation and he reentered the Continental army. He was killed in battle at New Haven, Connecticut, in April, 1777.

Quebec, The Capital of New-France, a Bishoprick, and Seat of the Soverain Court.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Images of Quebec

There are few views that portray Quebec between its founding by Champlain in 1608 and General Wolfe's siege of 1759. Thomas Johnston, a native-born Boston engraver, contributed to the public understanding of the news of the day with visual imagery. His view of Quebec was advertised for sale in the Boston News-Letter for August 16, 1759, as the British and New England forces were beginning their assault on Quebec, which would fall that September. Although the advertisement for the print states that it was done "from the latest and most authentic French original," it is actually based on an inset on a map by Nicolas de Fer published in 1718.

6.1. Fantasy Views of Quebec and Boston

Credits

Editorial Notes: Items Pending Integration

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library