Introduction

Traitez nouveaux & curieux du café, du thé et du chocolate

1685

-

p. 5

p. 5Invisible Sweetener

Sugar is an unseen but indispensible ingredient in this scene, as it was in so many images of polite conviviality in this period. This title page imagines the consumption of three increasingly popular beverages imported to Europe as a sociable meeting of a coffee-drinking Turk and a tea-drinking Chinese man. They sit and sip their drinks around a low table, while a Native American stands by (perhaps deemed too savage to share their table), bow in one hand and a large cup of chocolate in the other. While coffee, tea, and chocolate were routinely consumed at their points of origin without sugar, the soluble white crystals invisibly transformed these products into sweet consumables that appealed to European taste.

FREE LABOUR, or THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE WALL

1833

-

p. 1

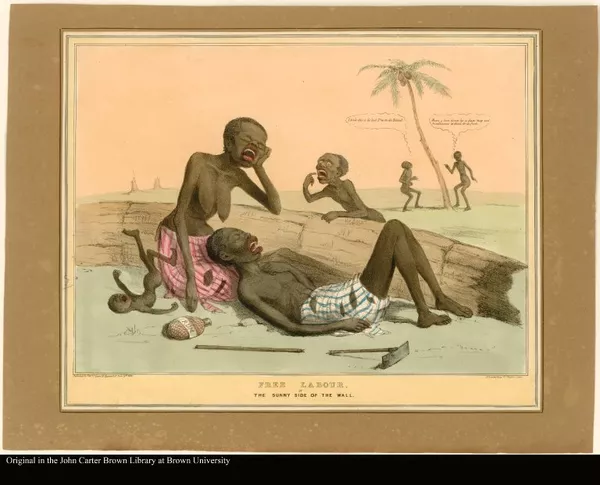

p. 1The Evils of rum and Freedom

Rum was a lucrative by-product of the sugar refining process. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries it was more likely to be pictured as a drink held by tipsy sailors in English caricatures than represented in allegories of colonial wealth or in diagrams detailing the stages of its West Indian production. In this pro-slavery satire, a flask of rum lays beside the dead or delirious figure of a former slave who can no longer labor and feed his starving family. This print promotes the argument repeatedly made by the West Indian interest that slaves were well-cared for by their benevolent masters, and were incapable of caring for themselves.

[Grinding.]

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Rum and Anti-slavery

This woodcuts link the production of rum by slaves to the negative effects of rum on slaves. Rarely do texts or images represent the entire system of sugar commodification from the cane field to markets in Europe.

The history of Jamaica. Or, General survey of the antient and modern sta...

1774

-

p. 9

p. 9Sugar was the engine driving Jamaica, Britain's most profitable colony in the eighteenth century, but it was not included on the colony's original coat of arms (1661). However, sugarcane was added as a grassy flourish to this engraving of the seal, which appeared on the first page of the most authoritative eighteenth-century history of the island. The double spray of cane serves as a discreet background for the seal, which features a helmet (sign of British imperial power), tropical exotics (pineapple and a crocodile) and figures representing the native Arawak Indians, who mostly had been killed or driven out of Jamaica, and displaced by African slaves.

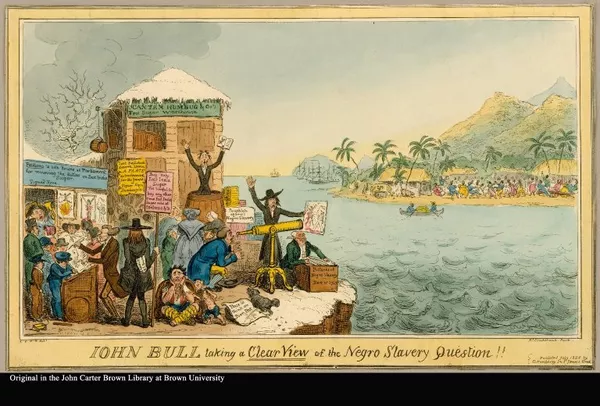

JOHN BULL taking a Clear View of the Negro Slavery Question!!

1826

-

p. 1

p. 1Icing Slavery

This pro-West Indian satire is notable for its unusual and witty use of sugar in its white crystalline form. It appears as a snowy substance that covers the ground and ices the roof of "Canten Humbug and Co's Free Sugar Warehouse." John Bull's telescopic view of the happy festive slaves on the shore of a West Indian island is obscured by the crude print of a slave being whipped, which a fanatical abolitionist waves before the lens. This pro-slavery print directly links the campaign to eliminate the duties on East Indian sugar with the campaign to abolish slavery in the West Indies.

Het Britannische ryk in Amerika

1721

-

p. 9

p. 9Sugar, Putti, and Heraldry

A long stalk of cane, with its flowering top, lies in the foreground, while two putti carry bundled cane and another holds a skimmer used in the boiling house. Cones of refined sugar are strewn about the foreground and held by another putto. To the far right, a lounging putto is sucking on a piece of cane. Putti were frequently used in the early modern period to represent industry and the arts. They do double duty here as stand-ins for black slaves and white consumers. The composition centers on and is framed by heraldic seals of corporate entities and the individuals to whom the book is dedicated (most were involved in the West Indian trade).

Sugar and Conflict

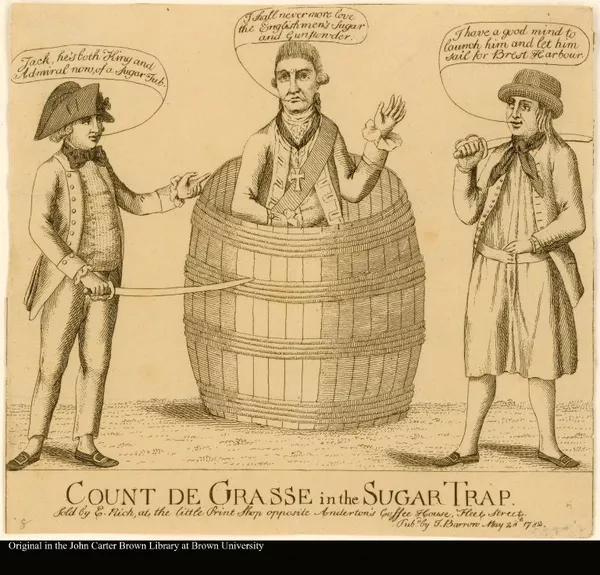

COUNT DE GRASSE in the SUGAR TRAP

1782

-

p. 1

p. 1Sugar Wars on the Seas (continue)

The defeat of De Grasse was treated in this naval battle scene showing his ship on fire, and mocked in this crude satire. In the satire, the French admiral is shown stuck in a sugar hogshead, and placed between Admiral Rodney and a British sailor.

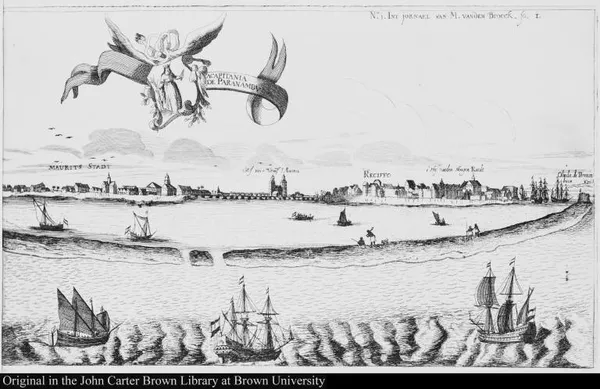

A capitania de Paranambuca

1651-1700

-

p. 1

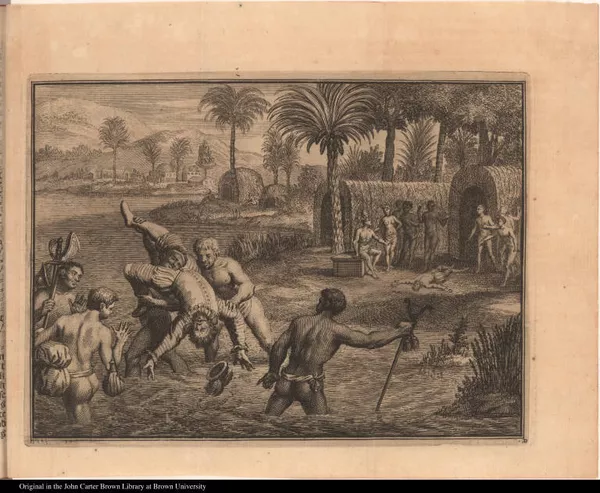

p. 1Mixing Work with War

This engraving represents an attack in 1645 by 1000 Portuguese rebels on a large Dutch sugar plantation that was defended by slaves wielding spears and clubs. The image oddly combines a battle scene with a traditional composite view showing the various stages of sugar processing—as if sugar-making would continue with a battle raging just a few yards away. The line-up of armed slaves doing battle echoes the manner in which a gang of slaves would cultivate a cane field, adding to the uncanny mixture of war and work.

Van den Broeck, who wrote the personal journal in which this print appeared, was a soldier for the Dutch West India Company in the late 1640s, when the Dutch attempted to put down a revolt by the Portuguese that led to the latter's takeover of Brazil in 1654.

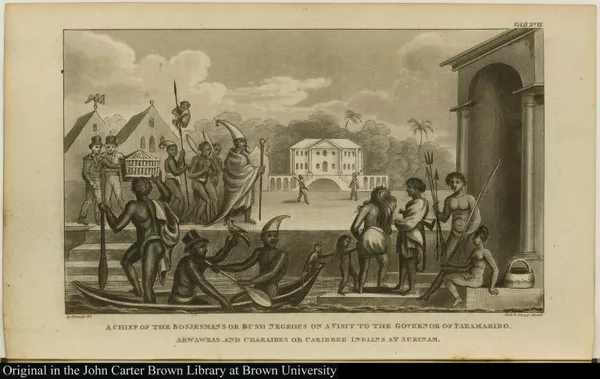

A chief of the Bosjesmans or Bush negroes on a visit to the governor of ...

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Hoes as Weapons?

The happy slaves on the left, dancing and playing instruments, are countered on the right by a vignette of slaves before a cane field and a planter. These energetic slaves, hoes raised in the air, seem to be threatening the planter rather than cultivating cane. Whether intended or not, this "confrontation" could be taken as an ironic reference to the threats planters faced from rebellious slaves in the West Indies in the decade before emancipation (1834).

[Grinding.]

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Aggressive Planting

There is little doubt that these three powerful slaves have more on their minds than just holing cane. The planter, whip held low, seems unaware of the violence that is about to erupt. The engraving is from an anti-slavery children's book that uses humor and irony, as well as sentimentality, to convey its message.

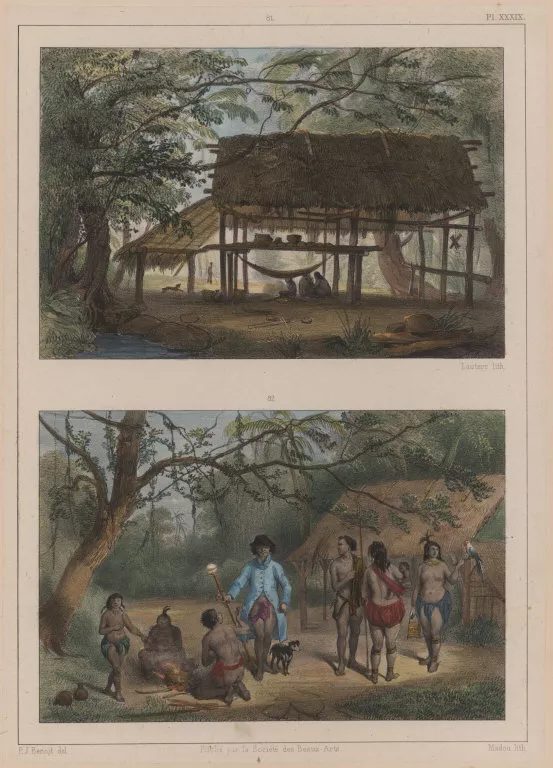

81. Un carbet. 82. Une famille.

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Nature, Calm, and Untamed

The lower image on this page is rather unusual. Storms and hurricanes were ever-present threats to sugar plantations in the Caribbean; they were often discussed, but rarely pictured. Benoit manages this natural threat first by pairing a calm scene with a stormy one, and second, by focusing on a slave hut, not a mill, cane field, or plantation house. These contrasted views might well have been interpreted as symbolizing the threat posed to the colony by the end of slavery. Storms often symbolized human conflict in nineteenth-century art. The British ended slavery briefly when they occupied Suriname, but the Dutch reinstated it, only abolishing it in 1863.

Mapping Sugar

This plott representeth the forme of three hundred acres of Land part of...

1646

-

p. 1

p. 1Imaging Deforestation

This partial plan of Fort Plantation in Barbados is regularly dotted with trees, denoting the forests native to the island; it also strikingly represents the rapid process of deforestation by showing tree stumps in the upper register, designated "fallen land" (under preparation for sugarcane planting), and in lower green sections devoted to pasture and potatoes.

A true & exact history of the island of Barbados

1657

-

p. 19

p. 19Barbados in Flux

In this map, the charming camels reference a doomed attempt to introduce them to transport hogsheads of sugar; the animals languished because no one knew how to care for them. The Indian marks a ghostly presence: most of the island's Caribs were killed, died of disease, or left after the Spanish invaded in 1492. The trees ornamenting the spaces on the map vanished quickly as land was planted in sugarcane: they were gone by the time this second edition of Ligon's book appeared. The hogs the Spanish introduced into the island fared better than the camels, trees, and Caribs: they multiplied successfully and were viewed as pests. They were hunted as runaway slaves were, and Ligon balances a scene of hog hunting (upper right) with slave hunting (upper left). This map raises the question of flux and change as it attempts to fix the island as an artful colonial space.

America: being an accurate description of the Nevv VVorld

1670-1671

-

p. 494

p. 494Mapping Connections and Difference

This outline map stresses Barbados' colonial connection to Britain by calling attention to hilly Scotland, the northern region of the island. This supposed topographical similarity is offset by the difference between colony and metropole suggested in the images that dot the rest of the map: the sugar mill with black slaves, tropical plants (pineapple, cabbage tree, papaw), and imported sugarcane.

-

p. 495

p. 495(continue)

The web of lines overlaying the map recalls the rhumb lines of the Mediterranean portolan chart, which denote particular compass headings for navigational purposes. This "faux" portolan feature lends a note of maritime authenticity to Ogilby's land-focused presentation and emphasizes the colony's connectedness to other sites in the Atlantic world.

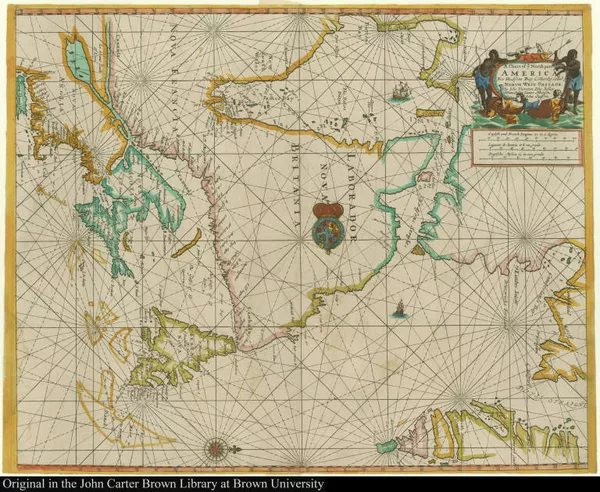

A Chart of ye North part of America For Hudsons Bay Com[m]only called ye...

1677

-

p. 1

p. 1Conflict and Measurement

Moxon's flamboyant reworking of a map of Jamaica by John Man celebrates the island as a British conquest held by force. Military banners bristle in the center of a display framed by two cannons. Animals and exotic plants serve as decorative space fillers for the unsurveyed areas. Moxon has represented ongoing conflict with a vignette of two men firing at each other—at either a great distance or very close, depending on how one reads their position within the triangular border of the unnamed parish that surrounds them. In the lower right, a black slave holds the map's scale in one hand and a bundle of sugarcane in the other. This vignette suggests that sugarcane and slaves are the true measures of this island.

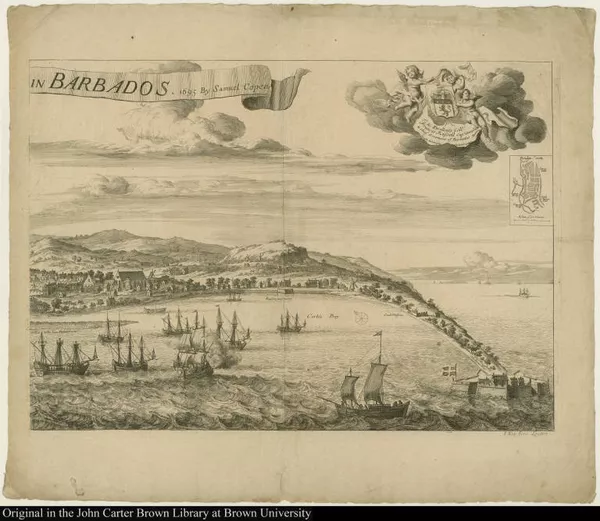

[A Prospect of Bridge Town] in Barbados. 1695 By Samuel Copen.

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Commerce as Movement

This bird's-eye view from the water testifies to the high productivity of sugar plantations in Barbados by picturing the island's only major harbor lined with warehouses and thronged with shipping.

[A Prospect of Bridge Town] in Barbados. 1695 By Samuel Copen.

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1(continue)

The ocean is shown churned up—not by a storm, given the fluffy clouds that ornament the view, but by the movement of ships. The agitated waves lend visual variety to a view lacking dramatic focus and also suggest the pulsing activity of the sugar trade out of this port.

A Chart of ye North part of America For Hudsons Bay Com[m]only called ye...

1677

-

p. 1

p. 1Sugar as Energy and Currency

This map is bristling with names and icons, suggesting the acceleration of agricultural development across Barbados at this time. Although the descriptive text under the smiling figures of Britannia and Plenty mentions that cotton, ginger, aloe, and other crops are grown on the island, the only commodity imaged on the map is sugar. It is depicted as icons denoting the energy source—wind, water, or cattle—used by mills to extract the juice from the cane. Ford got the Barbados assembly to pass an act prohibiting copying of the map—a strange gesture, since there were no copperplate presses on the island at this time. The penalty for printing the map without Ford's license: 2000 pounds of sugar.

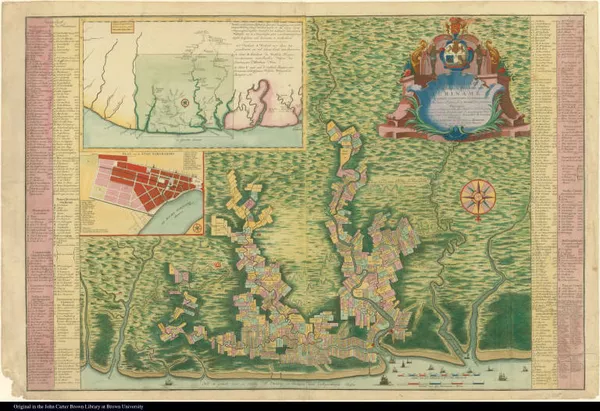

Algemeene Kaart van de Colonie of Provintie van Suriname, ...

1758

-

p. 1

p. 1Mapping Jewish Planters

This brightly colored display map advertises Dutch colonization in Suriname via the interlocking geometrical shapes of the sugar plantations that jut out from the rivers and spread into the green and yellow areas marking lands as yet undeveloped by Europeans. The conflict that comes with the establishment of plantation slavery is acknowledged by the bright red flames, which mark the location of a slave rebellion.

Half of Suriname's European population was comprised of Portuguese Jews, who established plantations on the savannah. On the map, their presence is denoted by the Jewish names mixed in with the Dutch on the plats and the lists of planters that frame the map, and by the words "de Joode Savanne" and "Joodish Dorp (village)" set in the yellow/green section of the map. This area was also occupied by communities of maroons (runaway slaves who formed their own settlements) and native peoples.

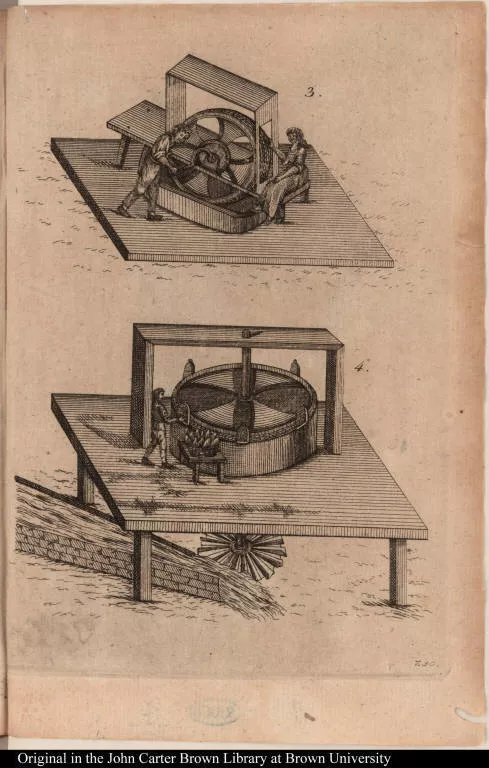

[Grinding.]

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Sugar Crossing the Waves

While sugarcane, mills, and plantations commonly appear as fixed icons on maps of the West Indies, sugar is rarely pictured in motion over the ocean—a crucial part of its journey from cane field to market. This illustration from an anti-slavery children's book places a hogshead of sugar on a small boat heading out to a transport ship bound for London.

The Natural History of Sugar

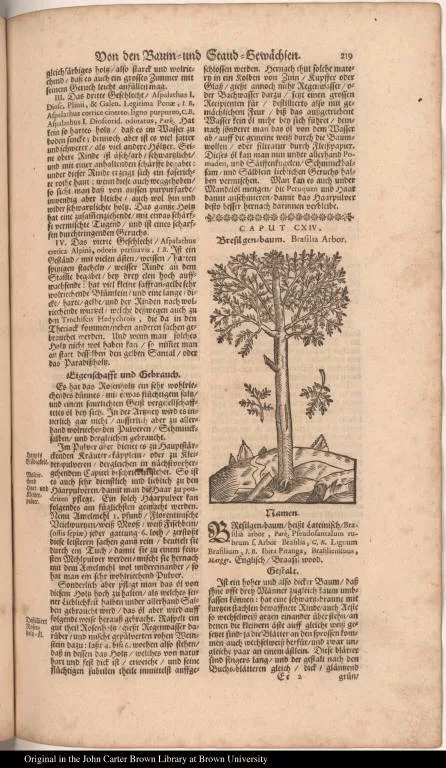

Bresilgen=baum. Brasilia Arbor.

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Flipping the Image

This woodcut appeared in an herbal that included plants from around the globe. The original image of sugarcane is taken from Willem Piso's Historia naturalis Brasiliae (1648). As in many prints that are copied from other sources, the Zwinger's copy is reversed. A design carved into a block of wood (or metal plate) will be reversed when printed, so copying directly from a print will result in a mirror image in the new print. Much of the history of sugar was created by re-using images and texts.

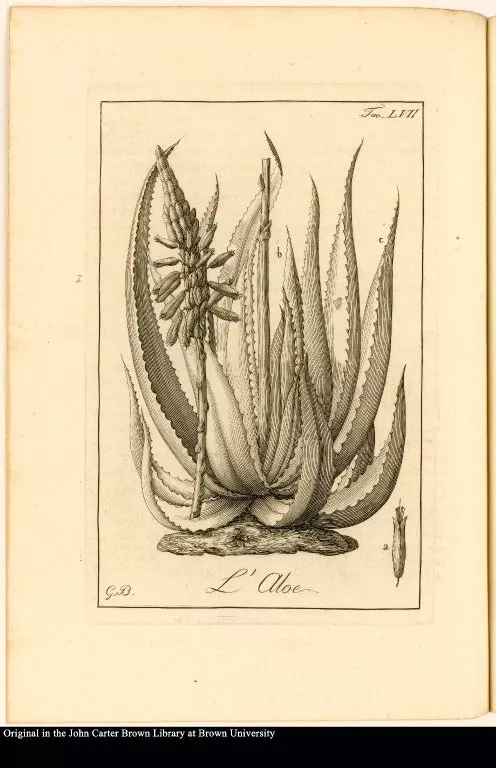

L'Aloe

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Harvesting the Specimen

The designer artfully crisscrossed the sugar cane's long, spear-like leaves to form a pleasing pattern across the surface of this plate. Human investment in the plant-as-crop is suggested by the stubs of canes, cleanly cut-off by a sharp tool.

The sugar-cane: a poem

1766

-

p. 6

p. 6The Poetic Specimen

One might not expect to find a botanical specimen in a book of poetry, but this image of a sugarcane serves as the frontispiece for Grainger's popular georgic poem celebrating the plant and its cultivation in the West Indies. Following the conventions of the natural history illustration, this simplified and generalized rendering of the leaves and cane is set against a blank background. Like Bordiga's engraving (see above), Grainger's illustration indexes the labor of slaves via sharply cut stalks of cane. Here the stubs frame the single stalk that remains, its crown of leaves expanding gracefully to fill the upper part of the page.

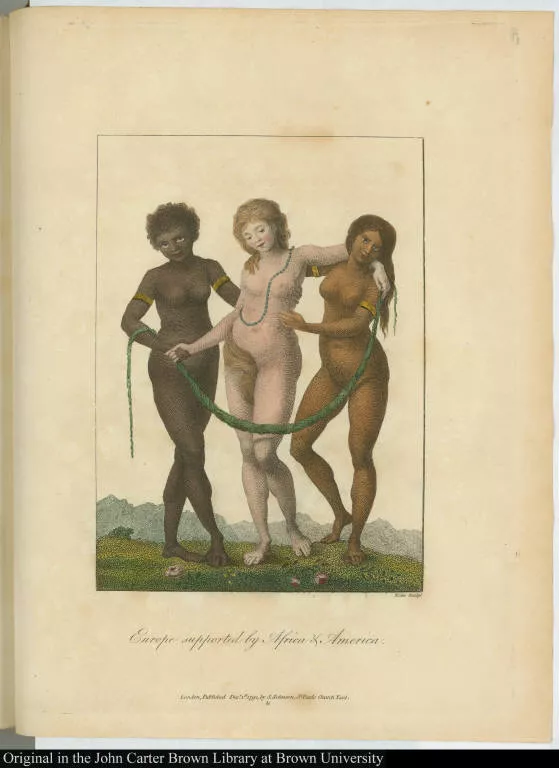

Europe supported by Africa & America.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Narrative of a Sugarcane

Stedman's Narrative is much more than an account of a military expedition against slaves in revolt. In chapter 13, vol. 1, there is a depiction of sugarcane that is more detailed than most contemporary natural history illustrations. The time involved in the growth of the plant is depicted as movement from the foreground space into the distance. On the left, and nearest to the picture plane is the cane when it first sprouts; next, the plant at half maturity; and farthest away, the mature plant with drooping leaves. Closing out the composition on the right is a fragment of cut cane, which stands outside this narrative of maturation. Shading and coloring gives this enlarged cane-piece a bold sense of presence, as if to underscore its economic importance.

[Grinding.]

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Cutting Cane

This wood engraving shows full grown cane together with cane that is cut. What the genre of natural history illustration is not designed to show is the effort expended in the labor of cutting. Here a black slave is cutting cane with something resembling a saber, which suggests the toughness of this plant.

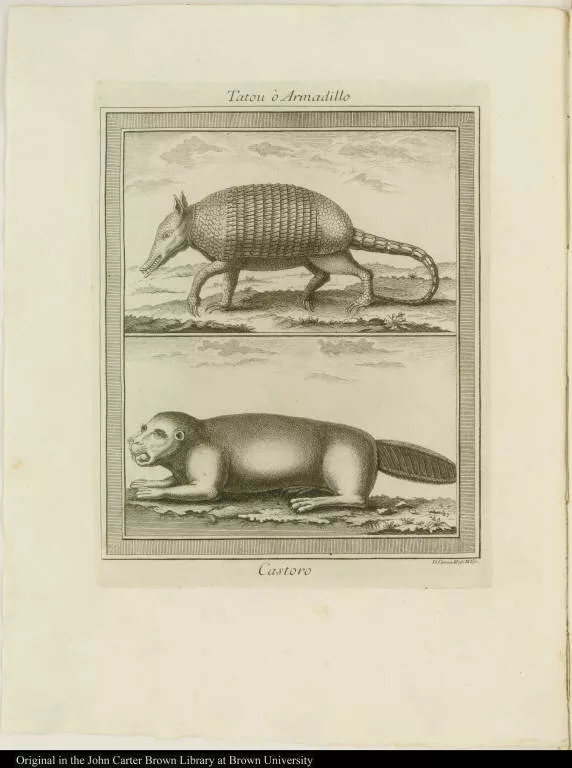

[top] Tatou ò Armadillo [bottom] Castoro

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Sugarcane as Heraldic Device

This Italian translation of an English New World history displays a specimen of sugar cane as though it were a coat of arms on a banner of animal hide waving above a view of a sugar plantation. Curiously, the leaves are shown with a hair-like fringe not found on the plant. The plantation view below shows vast fields of cane, with improbably-placed palm trees scattered among them. Slaves dot the landscape, while a double row of slave huts frames the scene on the left. Like other early modern images, slaves are not pictured here in the large numbers needed to produce such a huge crop. This engraving was reworked from a plate in the famous Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences compiled by Diderot and D’Alembert (1762). In the original illustration the sugarcane banner and the landscape were reversed and shown separately.

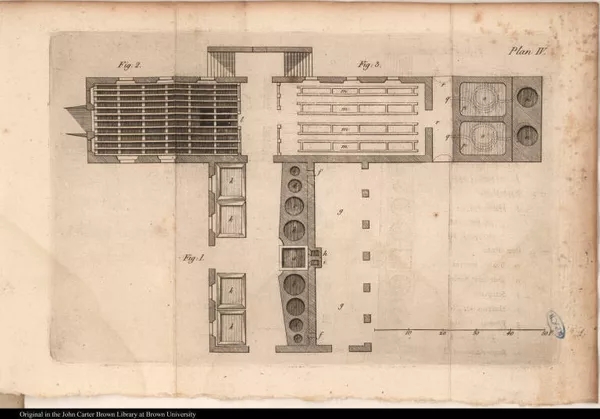

[Sugar processing factory]

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Sugar vs. Cotton

There were nearly equal numbers of cotton and sugar plantations in St. Croix in 1750, when the Danish were in control, but sugar came to dominate in the later decades of the century. This plate acknowledges sugar’s overtaking of cotton. It has numbered specimens of both plants, but gives more visual weight to sugar by presenting an elevated view of a cane plot with plants at various stages of growth. This figure is placed above that of tools used in sugar production: a cane-cutting knife, a hoe, and two views of a sugar skimmer.

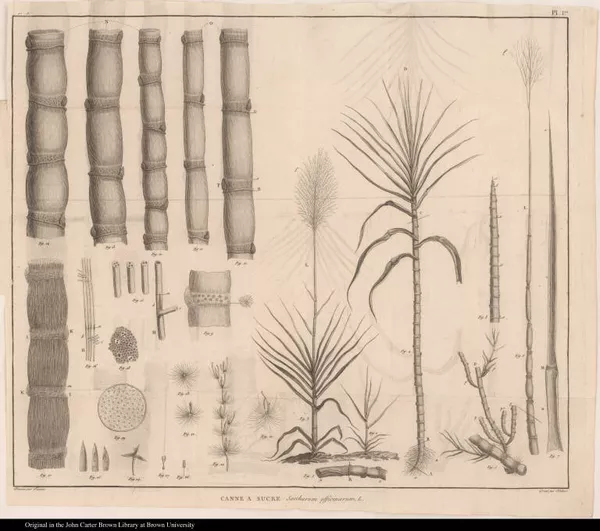

Canne a sucre Saccharum officinarum, L.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1The Comparative Anatomy of Sugar

Fossier’s plate represents the most detailed dissection of sugarcane published up to this time. It appears not in a work of natural history, but in the most authoritative treatise dedicated to improving sugar technology published in the eighteenth century. Improving the yield and quality of the commodity requires analyzing the plant in a scientific manner: that is the message of this image. Examples of healthy cane (figs. 12-14) are placed for comparison next to sections of cane with a “feeble constitution” (figs. 10-11). The scientific rigor of image is emphasized by the multiple ways the cane is shown under dissection. For example, in cross-section with the eye (fig. 18), under a microscope (fig. 15), and with a magnifying glass (fig. 16).

Fossier’s illustration of sugarcane retained its authority for at least 40 years. The plate was reproduced with its figures rearranged in George Porter’s 1830 account of sugar technology, which centers on an English translation of Dutrône’s book.

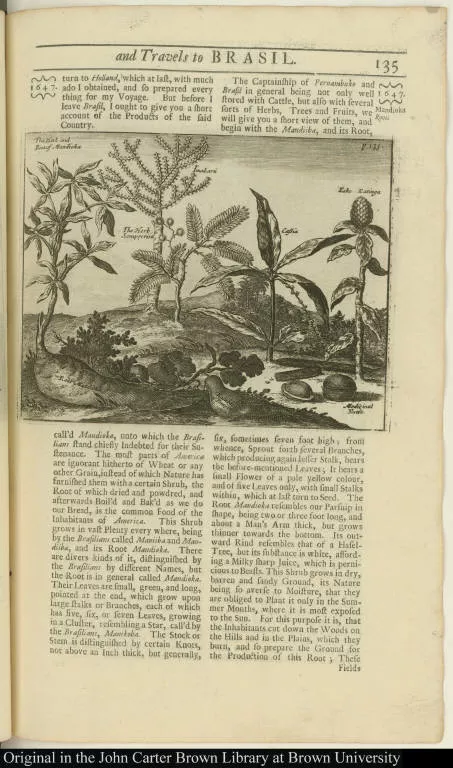

[Plants of Brazil]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Making Exotica, Domesticating Cane

The Dutch were known for their still life paintings as well as their accomplished skills in engraving; this print capitalizes on both. The designer and engraver used odd shifts of scale, fine engraving, and artful composition to create an exotic Brazilian still life. The sugarcane is a foreign transplant, but makes its place here among plants native to the Americas. The crossed pieces of cane, detailed and boldly textured, provide compositional balance for the two swelling papayas--one cut open as if in an eerie smile. In the highly compressed middle ground, sugarcane plants loom as large as the cashew and papaya trees that seem only a short distance away. Mixing still life with natural history illustration, this plate aestheticizes sugarcane and naturalizes its place among the native flora of Brazil.

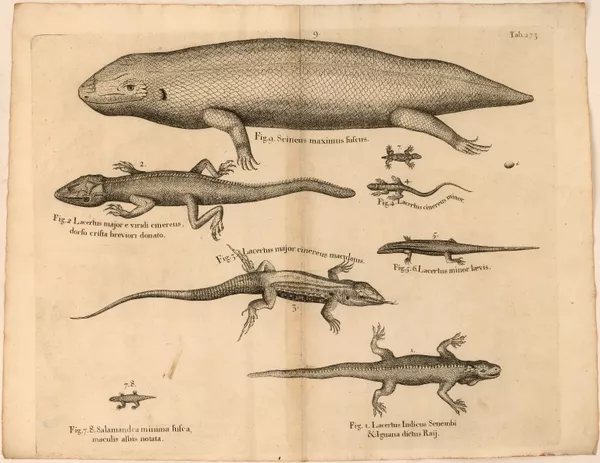

[Lizards, skink, salamander, and iguana]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1The Elusive Cana

Jamaica had become Britain’s most profitable sugar island by time this first volume of Sloane’s natural history was published. While images of a land crab, African instruments, Spanish coins, and a jellyfish are among those featured at the beginning of this volume, the sugar cane is all but buried. It appears in the section on grasses (botanically appropriate), and is shown with only its grassy top. The cane stalk, the focus of labor and the source of wealth, has been left off. This cropping was deliberate; this is clear when the engraving is compared with the actual specimen (see left) from which the drawing was made, which has a stalk over six inches long. Other specimens of tall plants in this volume are simply shown in two parts, so the problem of plant size does not explain the elimination of the stalk.

Sloane devotes consideration attention to sugar and plantation slavery in his text. The absence of the sugarcane image in the introduction suggests that this important commodity had ceased to be a curiosity, lacking the visual drawing power of the novelties displayed in the opening pages.

Sugar, Technology, and Slavery: The Plantation

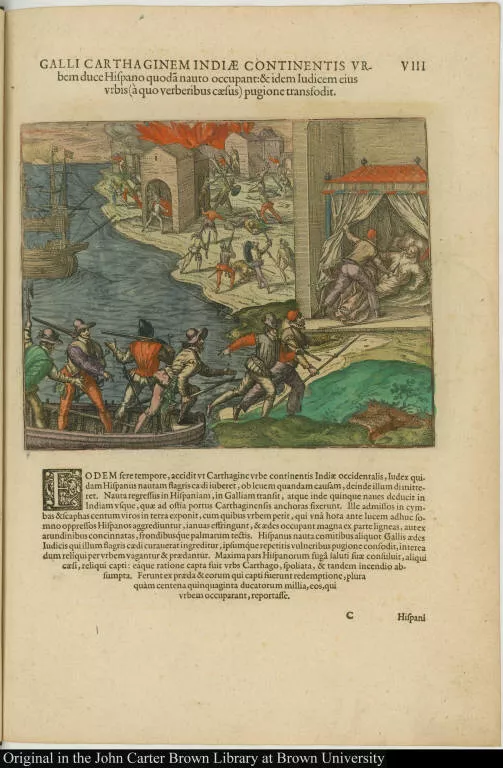

Galli Carthaginem Indiae continentis urbem duce Hispano quoda nauto occu...

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1Figuring Slavery

One of the first engravings of sugarcane milling and of slavery in America, this plate was made for de Bry's beautifully illustrated compilation of writings on the Americas; it illustrates Benzoni's history of the Spanish colonies. The text refers to the Spanish switching of black slaves to sugar production in Hispañola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) when gold mining ran out. Although the text identifies the figures as blacks, they are pictured as light-skinned. At this moment human difference was marked as much by culture (dress, religion, etc.) as by skin color, hair texture, and physiognomy. These figures' near nudity codes them as more savage than Europeans, thus candidates for enslavement. While processing cut cane occupies most of the composition, the viewer's attention is also drawn to distant cane fields by the smiling sun beaming down on the fields and laboring slaves.

Sucrerie

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1The Plantation as Curiosity

In this composite view of a sugar plantation in the French Antilles a white overseer, stick in hand, directs the actions of black slaves who scurry to take their bundles of cane off to the three-roller cattle mill in the background. As is common in this kind of view, cane fields are relegated to the background and shown here as a tightly compressed block. Less common is the focus on slave huts (marked 10 in the right foreground); usually they are placed in the distance when shown at all. The plate is also striking in its emphasis on tropical plants. Boldly modeled and outlined and placed like a screen in the foreground, the exotic trees and plants threaten to draw the viewer's attention away from the titular subject of the print. Natural history and production scene combine here to form a decidedly curious image.

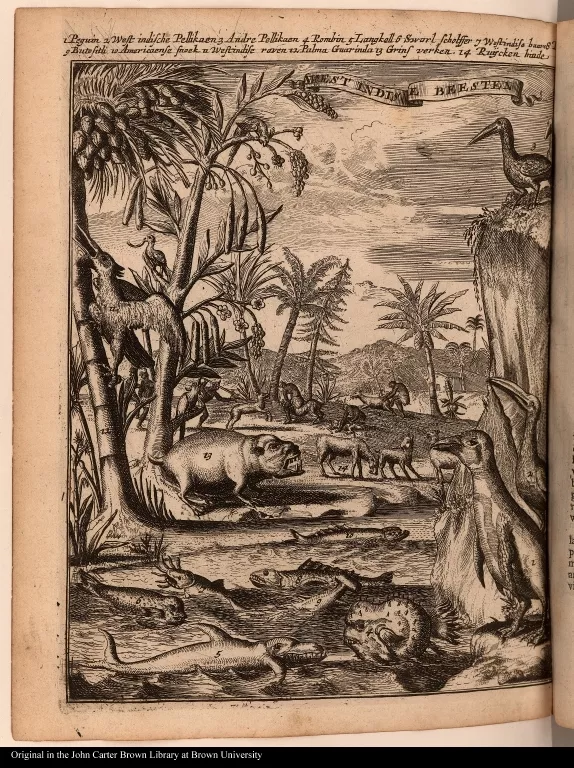

West Indise Beesten

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Up-scale and 'Natural:' Sugar in Brazil

The boiling house is foregrounded here; behind the slaves skimming and pouring sugar liquor are rows of cones. These are visual reminders that the Portuguese in Brazil commonly produced pure white crystals, rather than the crude muscovado that was imported to Britain, France, and Holland. Not one, but two large mills dominate the middle ground, one driven by cattle, the other water. They suggest the large scale of the operation in Brazil, where milling was often centralized and the labor force increased by planters renting slaves from other proprietors. This composite view has some of the liveliness and naturalism of contemporary Dutch landscape painting. Note here the light raking across the scene from left to right, the agitation of the water, and the hint of a breeze rippling though the sugarcane plants in the center.

[Grinding.]

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Doing Double Duty

The scores of composite views of sugar plantations published in the early modern period repeatedly draw on a limited set of scenes and visual elements that define important stages in transforming cane into crystals. Guarding introduces another element, highlighting the value of the sugarcane crop and the violence needed to protect it from animals and people. Sword in one hand and lance in the other, this slave seems ready to kill and harvest all at once.

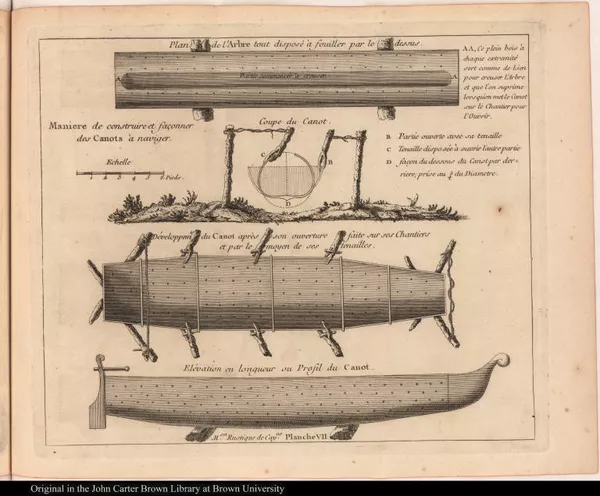

Maniere de construire et façonner des Canots à naviger.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1The French Country House Goes to Cayenne

This plate appears in a manual designed for new planters in the French colony of Cayenne. It contains two plans that offer idyllic visions of sugar plantations styled after a French country estate. On the left, the elaborate birds-eye plan includes a chapel and an olive grove, as well as a sugar mill and a cattle pen. The stress is on opulence and order: most of the estate is bounded by fences and organized by trees and paths set in straight lines. Like a French chateau, there is a formal garden, replete with ornamental fountain, next to the planter's house. The second plan (small, but still including a large formal garden) emphasizes surveillance: everything is organized along a narrow axis and the text states that all activities take place under the master's eye.

Here you may view the vast luxuriant Plains, The bounteous Mother of the...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Guarded Bounty

This frontispiece to a planter's manual celebrates the bounty of the sugar plantation in an amateurish image and georgic verse. Both word and image operate through excess. The verse is loaded with adjectives; in the image, leafy branches spill over the wall, and cane fields extend to the mountains. The estate's buildings are nearly obscured by the line of palm trees marching across the background. In the foreground two white men are inspecting cane plants, while a black slave cuts cane behind them. As in the previous two plates (to the left), guarding and surveillance assume visible form—here in the well-built wall with its guardhouse and large, pointed gates, which not-so-subtly frame the slave.

It is unusual to find a print engraved and published in the West Indies at such an early date, since presses for making copperplate engravings and, later, lithographs weren't imported until the nineteenth century.

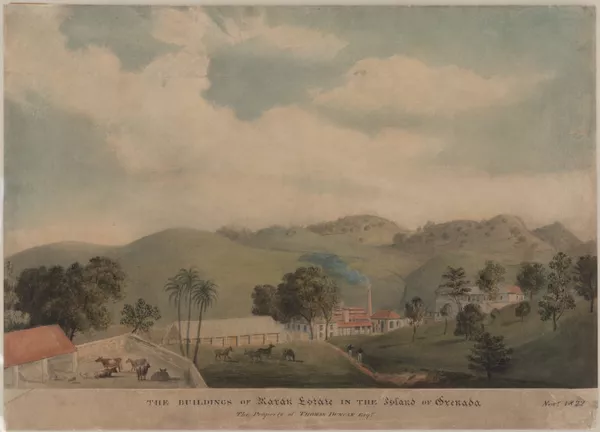

The Buildings of Maran Estate in the Island of Grenada. The Property of ...

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Imperial Georgic

This anonymous watercolor submits the agro-business of sugar-making to the conventions and ideology of georgic landscape painting. The georgic celebrates the bounty, peace, and harmony (social and visual) emanating from the agricultural landscape. This composition is harmoniously ordered through the rhythmic line of the green hills and the central trees that soften and partially obscure the buildings on the estate. Labor is banished almost completely—there are two slaves in the middle ground, but it is unclear what they are doing. The horses and cattle all seem to be at rest, although someone is working—given the blue smoke that pours from the chimney on the boiling house.

Sugar, Slavery, and Technology: The Mill

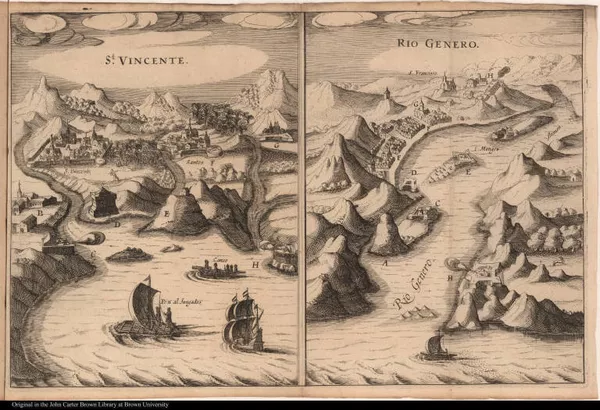

[left] St. Vincente. [right] Rio Genero.

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1The Edge Runner

In this view of the chief sugar region of Brazil, the river traces a map-like course, dividing the composition in half: the fort, the city, and the fields on the right are all shown from above. The scene of sugar processing (lower right) is dominated by an edge runner—the most primitive type of wheeled sugar mill used in the New World. The circular motion of the mill is animated through the repetition of its form across the composition—in the swirls of smoke coming from the boiler and from the huge fire in the distant mountains.

Historia naturalis Brasiliae

1648

-

p. 66

p. 66The Vertical Roller Mill

By the seventeenth century roller mills, rather the edge runners, were being used in the Americas to express the juice from sugarcane. This in an early woodcut of a vertical three-roller mill, in which the rollers are placed in a triangle, rather than in line. The bold lines of the curved walking beams frame this vignette, emphasizing the power generated by the ensemble of the machine, animals, and slaves, including the white men who closely oversee the process.

-

p. 67

p. 67

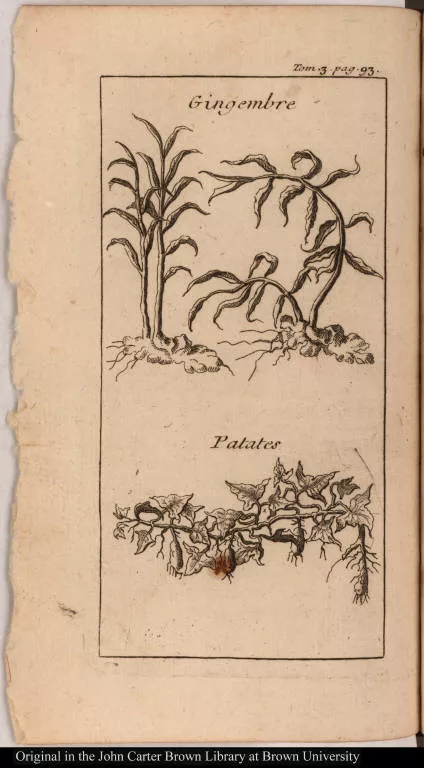

[top] Gingembre [bottom] Patates

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1The Horizontal Mill: from Coinage and Cotton to Sugar

This technical engraving seems to offer all there is to know about the construction of a water-driven roller mill. The parts, clearly delineated and labeled, are presented for inspection without sugarcane or laborers obscuring any part of the machine. There has been much speculation about the origins of the horizontal roller mill. Leonardo da Vinci devised a two-roller horizontal mill that was the model for a machine to roll metal for coinage. Horizontal mills were also used in India for processing cotton—and provide perhaps the most likely source for those developed in the West Indies.

Labat was a Dominican missionary who was in the Antilles from 1693 to 1706, and his Nouveau voyage contains many mill images. Catholic missionaries like Labat were crucial sources for information about sugar technology; several religious corporations, especially the Jesuits, owned sugar mills in Brazil in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

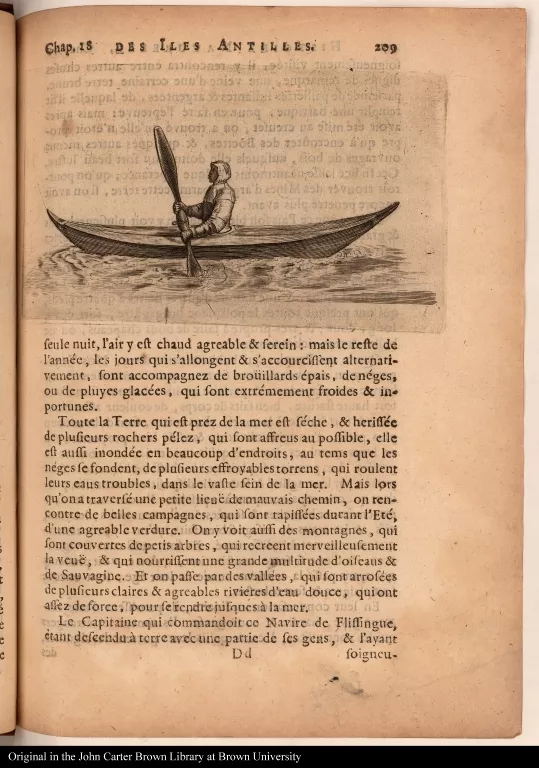

[Native American paddling a kayak]

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Softening Slavery

In this composite view a three-roller vertical sugar mill is theatrically framed by banners containing the labels for the various parts of the illustration. Two slaves thread the cane through in front and back of the rollers. Working long shifts during harvest, slaves were always at risk for losing fingers or worse in the rollers. The path of the cattle and attendant slaves in their endless journey around the mill forms a circle that orders the rest of the vignettes showing various stages of purification.

Two scenes on the right suggest a positive relationship between masters and slaves. In the lower right a slave looks out and smiles at viewers to engage their attention. Behind him a white man looks solicitously at a slave carrying a bundle of cane.

La Figure des Moulins a Sucre

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Centering the Mill

The engraving for this smaller edition is less bold, and also evidences less concern for slaves than the version of the print from the Rotterdam edition (above): the image of the white man looking with concern at a slave (on the right) has been eliminated in this edition, as has the smiling slave in the lower right.

The vertical roller mill may have come to the Americas from China; if so Jesuit missionaries would have been likely conduits for this innovation.

[Manioc mills]

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Technology Trumping Labor

This plate is a celebration of the combined power of technology and water. The three roller vertical mill is placed within a grid-like space where everything seems measured and under control. The image suggests that the human labor needed to work this mill is so minimal that one white woman, dressed as a servant, can operate it—although one might worry about that dainty hand, so close to the powerful rollers.

Fishing Canoe.

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Women and the Mill

The previous plate improbably imagines a white woman operating a mill. Black women did perform this labor, although they are seldom pictured working at the rollers in early modern prints. This nineteenth-century image of a mill in Brazil puts black women in the picture, drawing the viewer's attention to them by showing them wearing brightly patterned skirts.

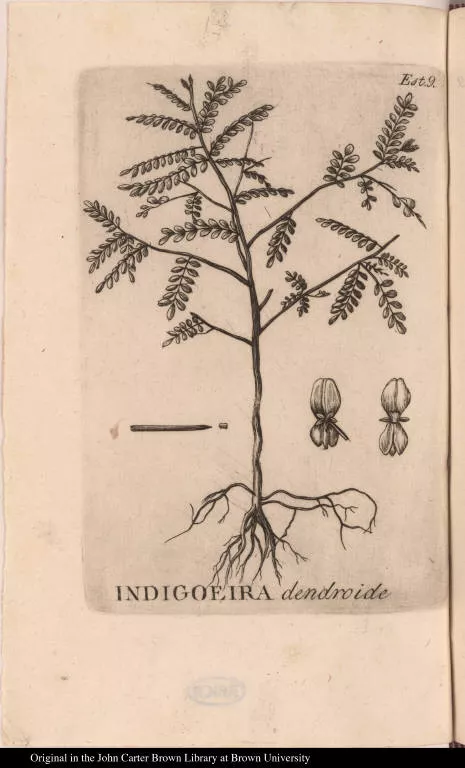

Indigoeira dendroide

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Space not Place

This plate displays innovations in the rollers and the system for delivering the cane to the mill. Unlike other compositions, which imagine some kind of physical location, this engraving sets the mill in the notional space of the technical drawing. Lines form corners in the background that denote the idea of space, but not a place. As for scale: How could the diminutive slave feed cane into these huge rollers? Where would he stand?

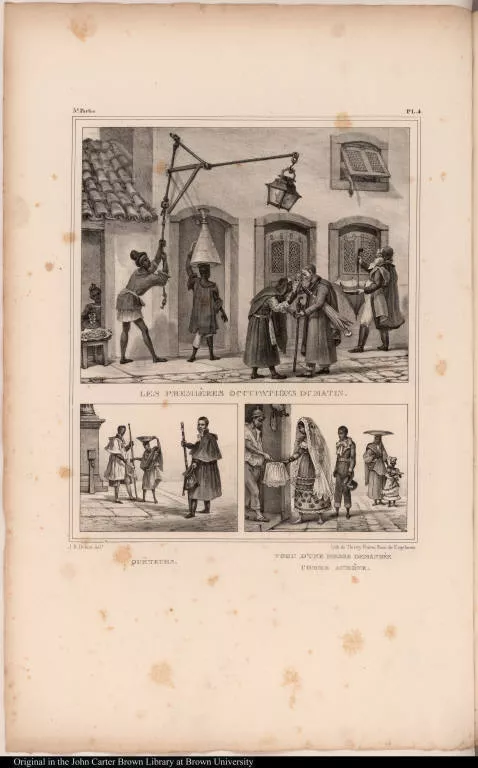

[top] Les Premières Occupations du Matin. [bottom left] Quèteurs. [botto...

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Milling Cane to Make Lemonade

This lithograph shows a portable sugar mill used for making liquid sugar extract. This liquor was used to sweeten lemonade made in Brazilian cities. Debret turns the conventional image of an agro-industrial sugar mill into an urban curiosity. The three-roller mill appears simply to have been miniaturized, with the powerful bodies of slaves taking the place of cattle or horses. And yet, because of the mill’s scale and placement, it looms large, resisting domestication. It is hard to imagine that the slaves could fully turn the long walking beams driving the rollers.

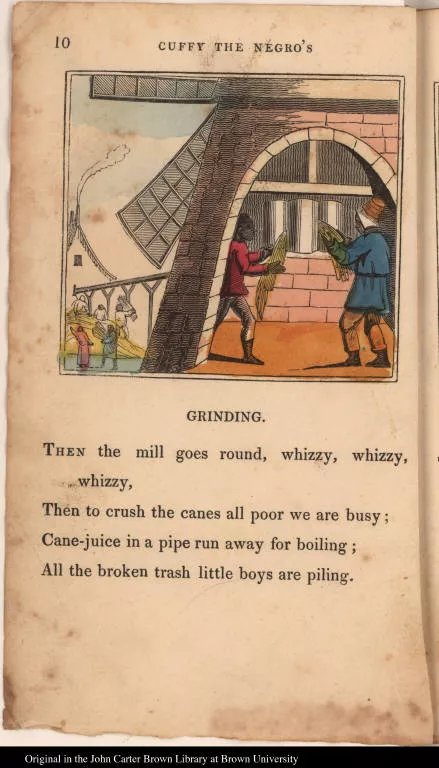

[Grinding.]

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Working around the Clock

Speed is a factor in processing sugar cane. The juice goes sour quickly, so the mill and boiling houses operate around the clock during harvest time. Mill images tend to be static, because they are conveying a technology and a process, not the experience of human labor. This plate of a three roller wind-driven mill from an anti-slavery children’s books uses doggerel verse to convey the speed and human effort (including that of children) involved in grinding.

Sugar and the Specter of Cannibalism

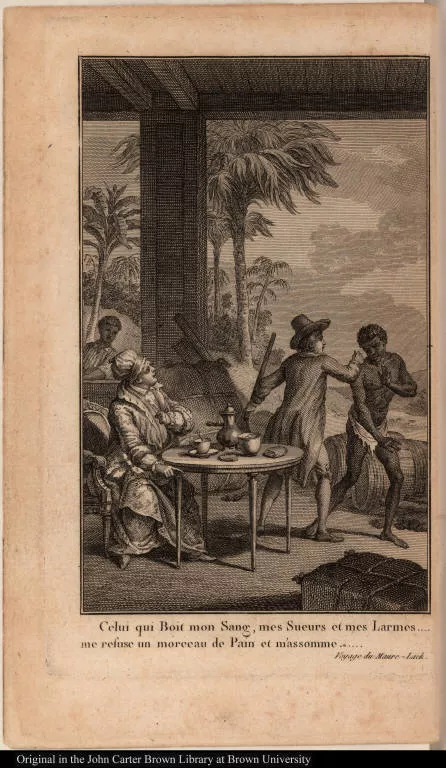

Celui qui Boit mon Sang, mes Sueurs et mes Larmes ... me refuse un morce...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Blood, Sweat and Tears

This frontispiece for an anti-slavery tract, likely written by a European posing as a slave ("Le More-Lack"), emphases the blood, sweat, and tears expended by a slave in producing the sweetened beverages on the table in this West Indian scene. While the image shows a white man beating a hungry slave, the even more horrible specter of white cannibalism is raised only in the inscription ("Those who drink my blood, my sweat and my tears … refuse me a piece of bread and beat me").

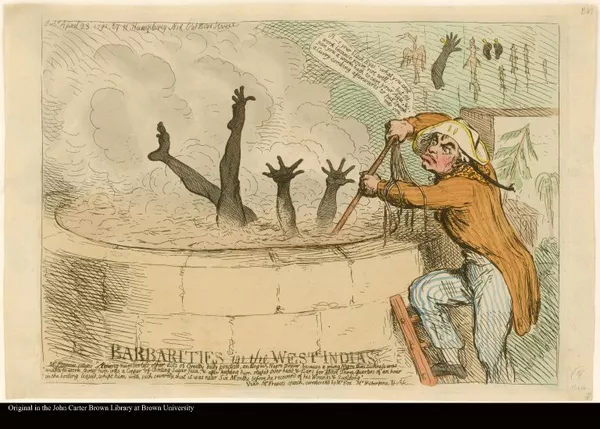

BARBARITIES in the WEST INDIES

1791

-

p. 1

p. 1Caricaturing Atrocity on a Sugar Plantation

Gillray appropriates the abolitionist trope of white cannibalism, transforming a sugar vat into a cannibal's pot. The slave is reduced to desperately waving appendages that set up a ghastly resonance with the black arm and ears tacked up on the wall next to some vermin.

This pro-slavery print is a satiric effort to discredit testimony given before the British Parliament during debates on ending the slave trade. The testimony claimed that a white slave driver had thrown a slave into a vat of boiling sugar as punishment. Caricature depends on exaggeration, and here Gillray maximizes the horror in order to show how supposedly absurd abolitionist testimonies of such atrocities were.

West Indise Beesten

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Cannibal Hell

In a hellscape compressed into the foreground, these Brazilian natives represent the height of exotic barbarism; wearing elaborate headdresses, they cook a human in a pot. Animal parts and a human leg hang overhead. This grisly collection of parts eerily resonates with the one on the wall in Gillray’s Barbarities, published a century later. While the British caricature is deeply satiric, this Dutch print indulges in a bit of wit by way of contrast: the cannibals’ cooking pot echoes the round bath containing indigenous Virginians in the Arcadian background.

[Native Americans throw a European into a stream]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Elegant Cannibals

Tupinamba (from Brazil) prepare a human victim for boiling in this engraving that illustrates a republication of an early account (1557) by Hans Staden of cannibalism in the New World. Unlike Gillray's monstrous slave driver, the cannibals in this early eighteenth-century engraving are represented as idealized nudes. The standing female in the center manages a graceful pose as she raises the victim's severed arm. Horror and aesthetic pleasure are both on offer here.

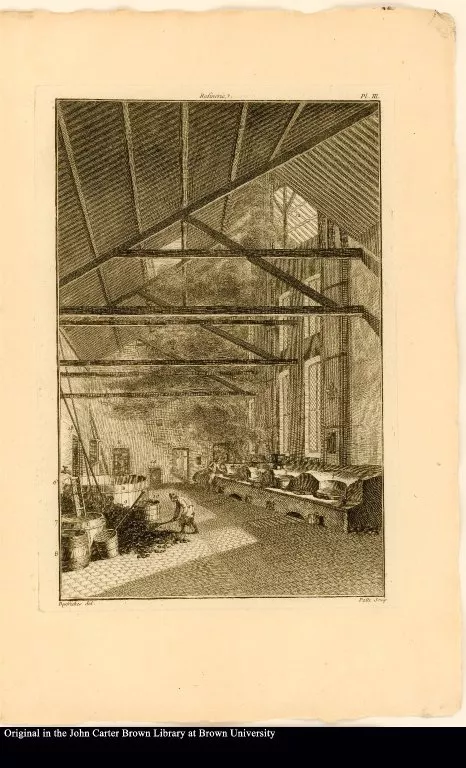

[Interior of a sugar mill]

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Blood in the Refinery

This illustration comes from a detailed account of sugar refining in Orleans. Cattle blood was used in the refining process—revealing yet another link between blood and sugar beyond those made by abolitionists a few decades later. The cask labeled 8 (on the left) contains cattle blood. According to the text, such casks were usually placed outside the boiling house because of the bad odor. The author claims that when the refinery was at full capacity, it was necessary to import cattle from Paris to provide enough blood for the process of clarifying the liquid sugar extract.

[Grinding.]

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Blood, Refinement, and Pollution

This page showing sugar refining in England (rarely pictured) makes a sly double reference to blood, refining, and pollution. As the verse below the image suggests, the baker seems to be adding a dark liquid, like blood, to the sugar cones: this references both the practice of clarifying sugar with cattle blood (see image to the left) and the abolitionist campaign against “blood sugar.”

Aestheticizing the Landscape of Sugar: George Robertson's Views in the Island of Jamaica & G. W. C. Vorduin's Views of the Dutch Sugar Colonies

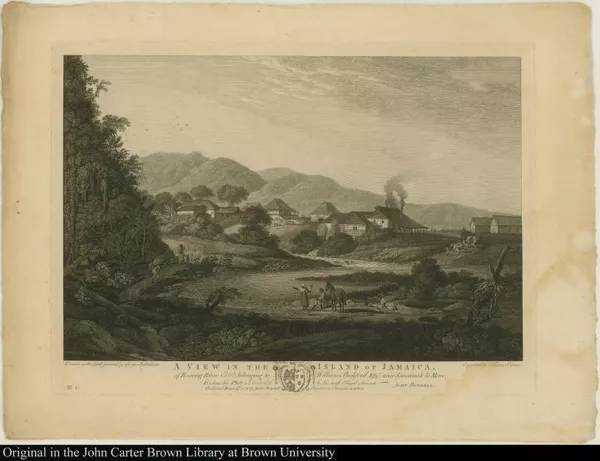

A View in the Island of Jamaica, of the Spring-head of Roaring River on ...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1The Plantation as Artful View

Framing trees, a road and river winding into a bright distance ornamented by billowing clouds, small figures called "staffage": all of these elements from European landscape painting are used to aestheticize this view of the grounds of a sugar plantation owned by the artist's patron. There are slaves in this scene, but they are driving cattle and selling fruit, not cultivating sugar. In the foreground a woman, coded by her dress and skin tone as mixed race, buys produce from a kneeling slave. This vignette echoes an imperial motif, often used in book illustrations, in which kneeling figures personifying the continents offer up gifts to Britannia.

A View in the Island of Jamaica, of Roaring River Estate, belonging to W...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Banishing Labor to the Shadows

This idealized view of William Beckford of Somerley's plantation is the only one in the set that depicts buildings involved in sugar production. The roofs of the mill and other structures are nestled picturesquely below the mountains; the smoke breaking the horizon serves as the most visually striking sign of human activity. Slaves ornament the view, but the only labor actually pictured takes place in the shadows on the left: here a slave is bent over carrying a large bundle of cane. This figure echoes those of English rustics carrying wood that populate the works of artists like Thomas Gainsborough. Here and throughout the series, the artist works to make Jamaica beautiful and somewhat exotic, but also familiar.

A View in the Island of Jamaica, of the Bridge crossing the Cabaritta Ri...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Claude Goes to Jamaica

The motif of the "bridge in the middle distance" was made famous by French seventeenth-century painter Claude Lorrain in his many idealized scenes of Italy, and it was often copied by later European artists. Here Robertson uses this device to associate this Jamaican scene with some of the most highly regarded landscapes in the canon of art. The figures provide a pleasing point of interest in the foreground (but laundering bed sheets in what appears to be a fast moving river, then hauling them out to dry, would be no small task).

A View in the Island of Jamaica, of part of the River Cobre near Spanish Town.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Domesticating the Tropics

At first glance this looks like a picturesque view of England's Peak District, with its swelling hills and winding rivers. The artist has offered up a scene that is both familiar and exotic: there are palm trees on the densely-wooded hillside, but they are not calculated to stand out as icons of tropicality. As in Dutch and English landscapes, small figures are seen on a winding road. European rustics morph into slaves that seem to have no masters and never venture near a cane field.

[De Reede van Paramaribo]

1851-1900

-

p. 1

p. 1The Touristic Gaze

Jaglust was a coffee plantation and Suzanna’s Daal a sugar plantation that were located on the Suriname River. The image renders the two plantations as tourist sites viewed from a passing riverboat. The text offers details about the sugar mills and the process for making sugar, noting that most of the ninety sugar mills are steam powered. The image however, offers few hints about the activities taking place in the buildings onshore, except for the smoke stack that likely marks the boiling house.

[De Reede van Paramaribo]

1851-1900

-

p. 1

p. 1Plantation Discipline vs. Artful Irregularity

In this view of a slave village in Suriname, the artist strives to accommodate opposing organizing principals: 1) Regimentation—seen in the regularized placement of the huts along a central axis, which displays good plantation management. 2) Picturesque variety and irregularity—achieved through the use of dappled shadow, the placement of trees to break the horizon line, and the figures. Pictured with un-modulated black skin and bright clothing, the slaves add “local color” to the scene. In nineteenth-century Europe black skin was often deemed aesthetically inferior to white, but that didn’t prevent black slaves from becoming picturesque.

[De Reede van Paramaribo]

1851-1900

-

p. 1

p. 1The Elegiac Cane

This elegiac image of the small volcanic island of Saba is the final plate in this lithographic set. Voorduin’s text stresses the Edenic nature of this island, with its mild climate, fertile valley, and relatively bloodless history. In the lithograph, the island seems to float on the placid sea. Delicately tinted in pinks, blues, and greens, the scene seems more visionary than topographic. An uprooted sugarcane plant floats in the foreground, evoking, perhaps, the general collapse of the sugar and slave economy in the Dutch colonies.

Teaching Plantation Discipline after Emancipation

Cutting the sugar-cane

1801-1850

-

p. 1

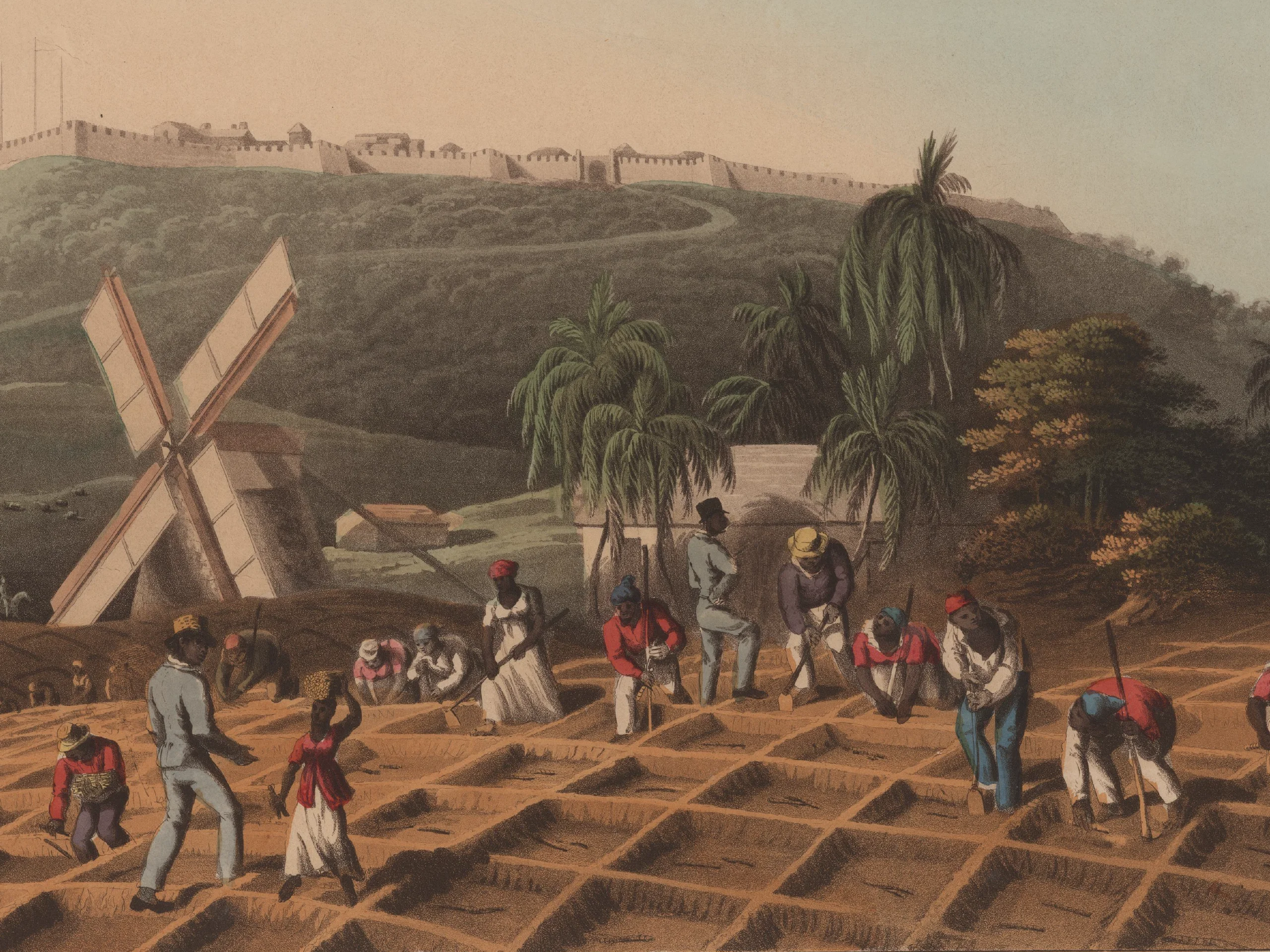

p. 1The Grid and the Fort

The laborious task of digging holes and placing sugarcane cuttings in a grid-like pattern is pictured here in some detail. This labor was overseen by black slave drivers, shown in hats with high crowns. Also overseeing the field is the fort (Monk's Hill) dominating the hilltop. The boldly marked grid and the crenellated fort operate in tandem to emphasize the ideas of surveillance and order that were so central to a plantation economy.

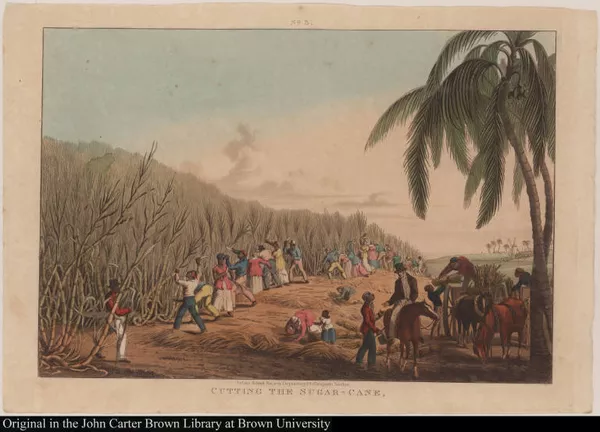

Cutting the sugar-cane

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Endless Harvest

This print emphasizes the size of fully-grown cane and the size of the labor force needed to harvest it. The towering plants twist and turn, almost as if they were alive, and the line of laborers seems as endless as the cane field. The hierarchy of the cane field is encapsulated by the conversing figures in the foreground: the white planter or overseer looks down from his horse to speak with the black overseer in the red coat, who has removed his hat in deference.

Cutting the sugar-cane

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1The Static Mill and the Well-Dressed Worker

People and animals are busily working here, but it is the powerful windmill that drives the scene. It is unclear how this can be the case, since no wind ruffles the palms that press into the scene, and the vanes of the mill seem still. Throughout the series black figures are well dressed (no rags or bare torsos). As if to call attention to the care for clothing, the artist shows two coats hung up next to the rollers—their owners involved in the dirty and dangerous work of feeding in the cane.

Cutting the sugar-cane

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1White Judgment, Black Labor

Acts of judgment were key to the appreciation of art and to making good sugar, and both were associated primarily with white men. On the right white men assess the quality of brown muscovado sugar, while black male laborers on the left work over the boiling coppers. Boiling cane was the province of black men, not black women, and was seen to require more skill than field work. In this well-ordered scene, even the smoke never strays: it goes straight up and out of the building, appearing as well disciplined as the laborers.

[Grinding.]

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1Picturing Sugar for Children

The two most extensive pictorial accounts of sugar making in this exhibition are in publications designed for children. The Clark aquatints that the JCB’s lithographs are based on have been widely reproduced in histories of slavery, the West Indies, and sugar making. The Cuffy wood engravings, by contrast, are virtually unknown. The work of manuring, shown here, has rarely been pictured in books detailing sugar cultivation.

Credits

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library