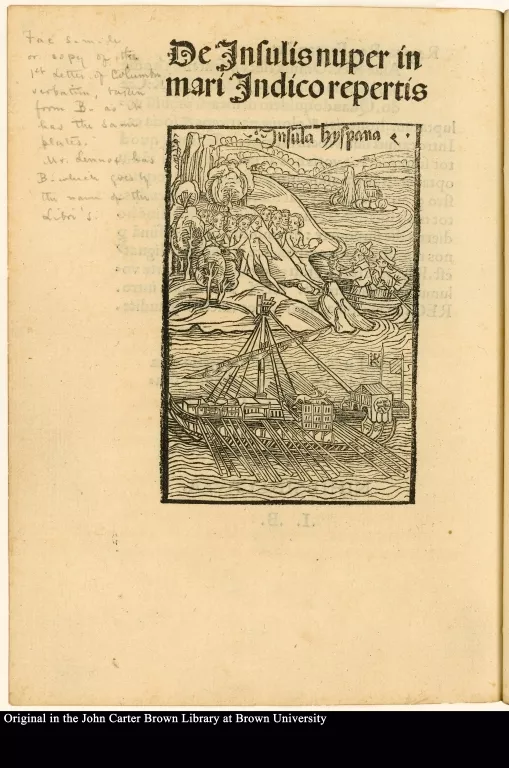

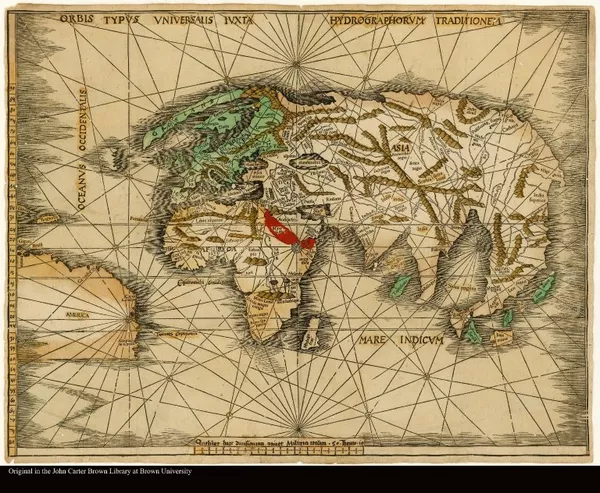

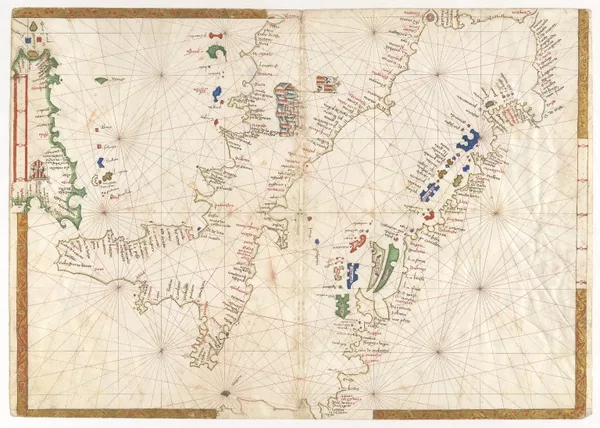

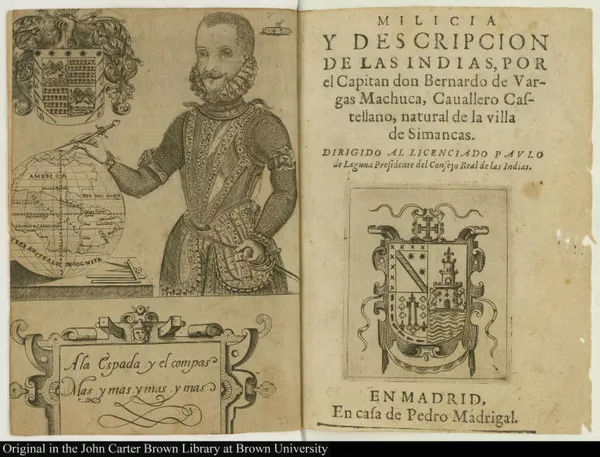

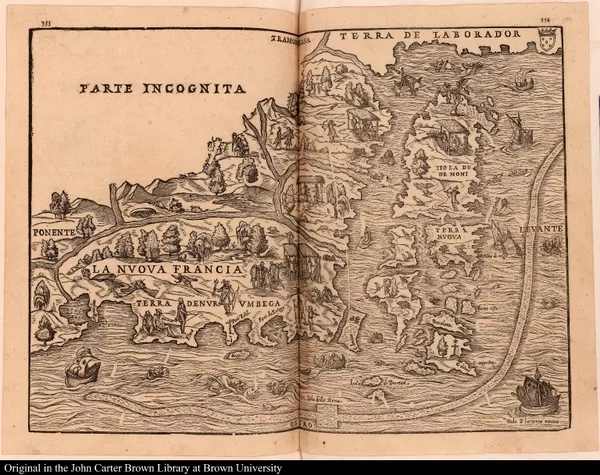

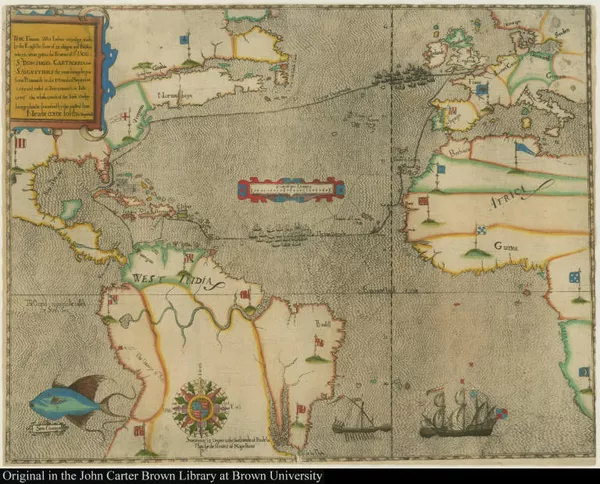

Although Portuguese success in utilizing exploration to develop new trading contacts with the East was obvious and enviable, Spain was in no position to undertake costly exploratory ventures until the country was unified as a Christian nation-state under Ferdinand and Isabella, the crowns of Aragon and Castile. After the defeat of the Moors at Granada in 1492, Spain was able to look outward, and Christopher Columbus, who had long tried to interest a backer in his plan to sail west to reach the East, appealed to the Spanish sovereigns at an opportune time.

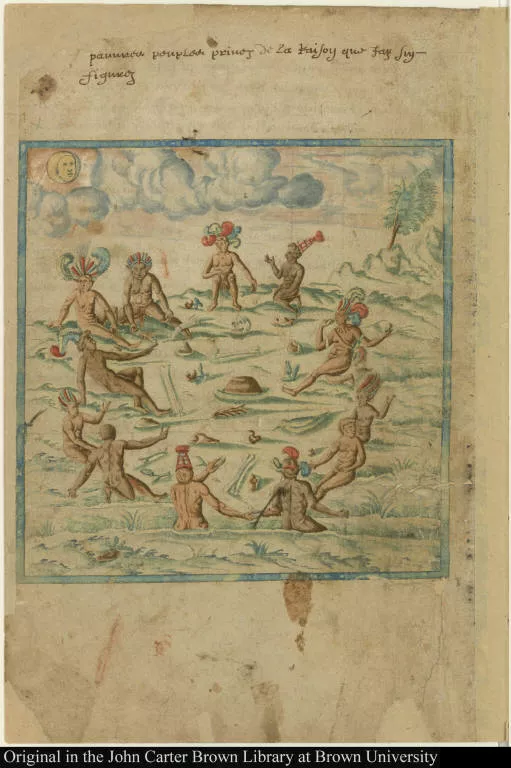

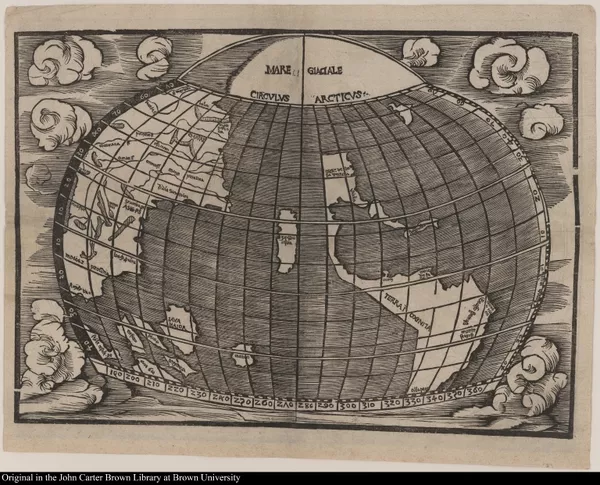

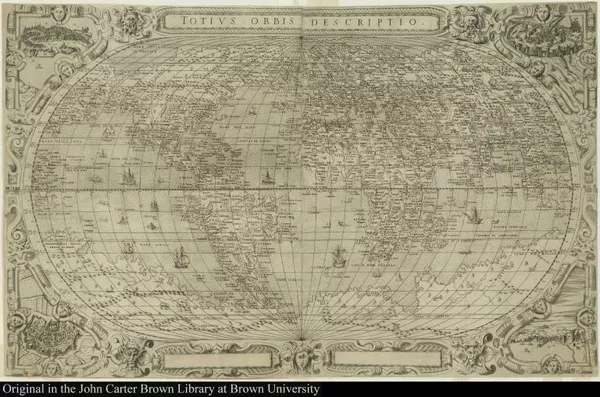

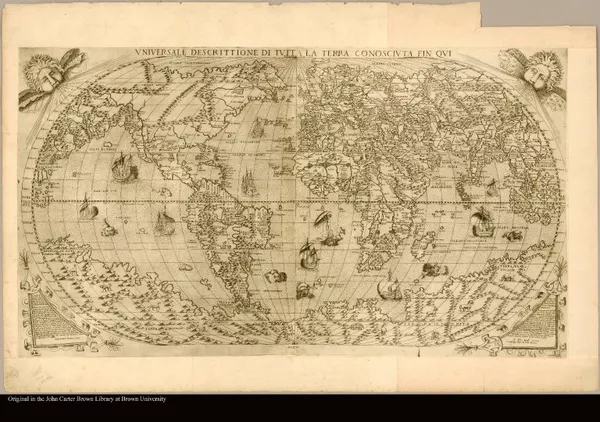

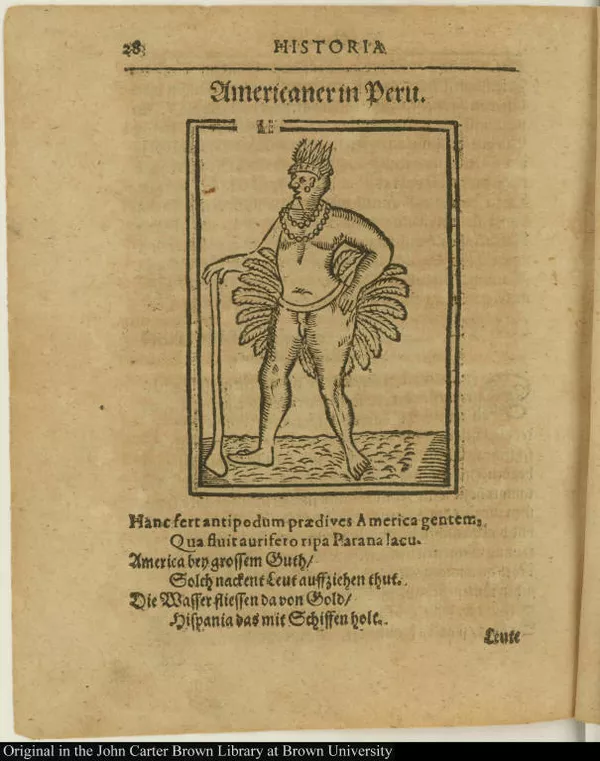

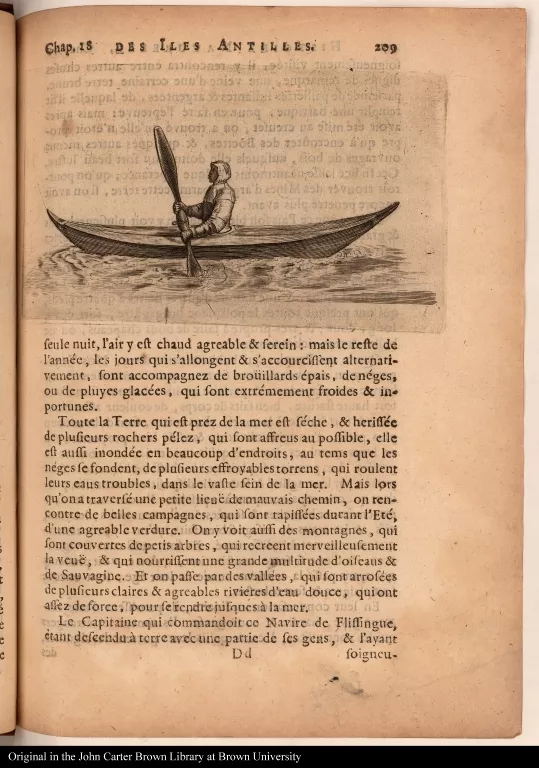

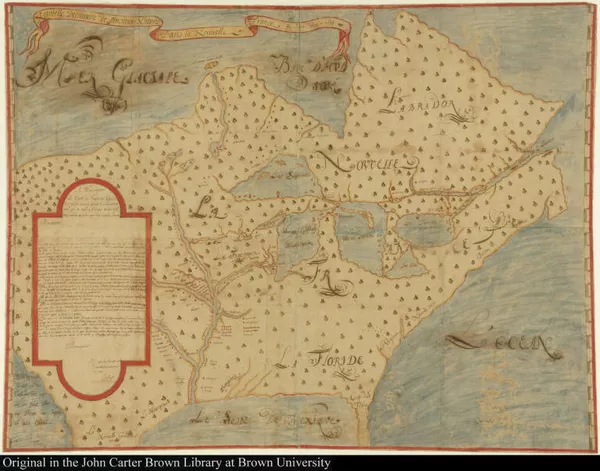

Columbus made landfall on an island in the Bahamas that the native inhabitants called Guanahani (the actual location of which is the subject of lively debate even today), where he was met by people “who went about naked without shame.” To the questions of where he was and who these people were the Discoverer did not hesitate in answering that he was on an island off the shore of Asia, and that the people were, undoubtedly, Indians from the Spice Islands (even though they were not quite as he had expected them to be). That neither answer was correct became apparent to others, if not to Columbus himself, fairly soon. Columbus’s confusion is indicative of the difficulty Europeans initially faced in assimilating new information and relating it to their conventional world-view.

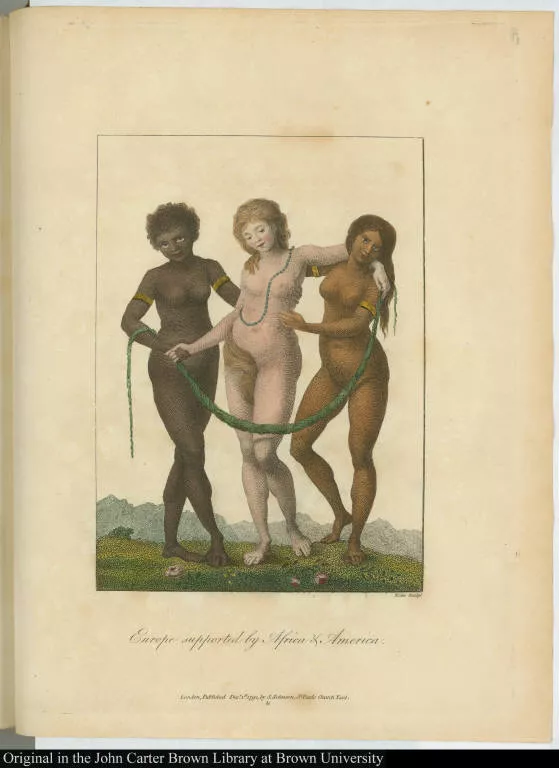

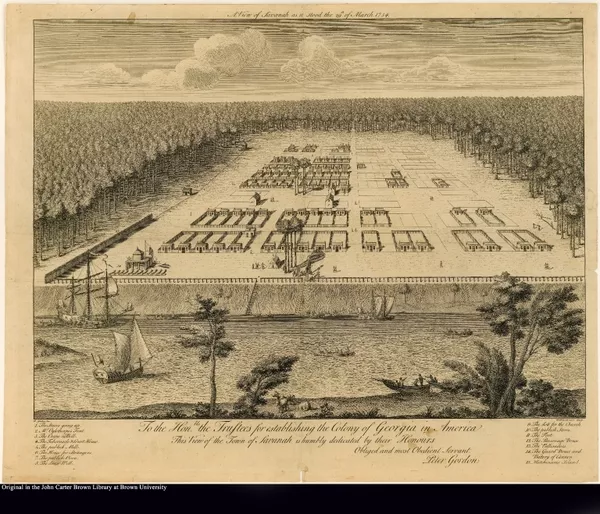

Christopher Columbus would much rather have encountered sophisticated orientals than the “children of nature” who met him with guilelessness, generosity, and a few gold ornaments. But his missionary enthusiasm and his practical outlook made him see the positive side, observing, “how easy it would be to convert these people... to make them work for us.”

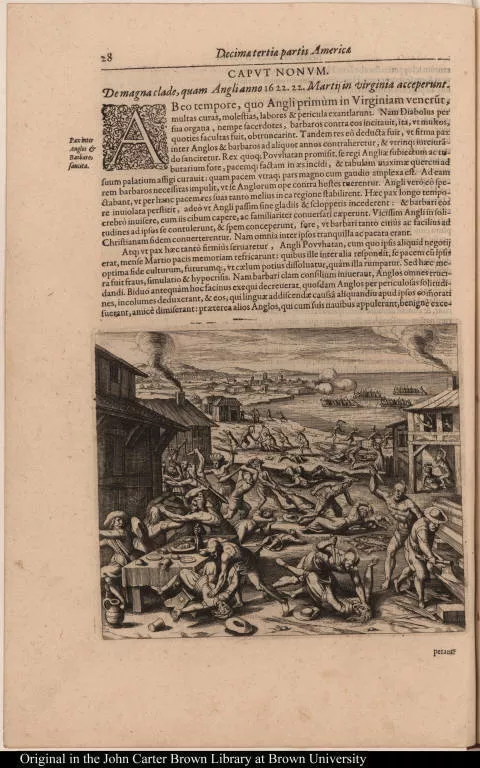

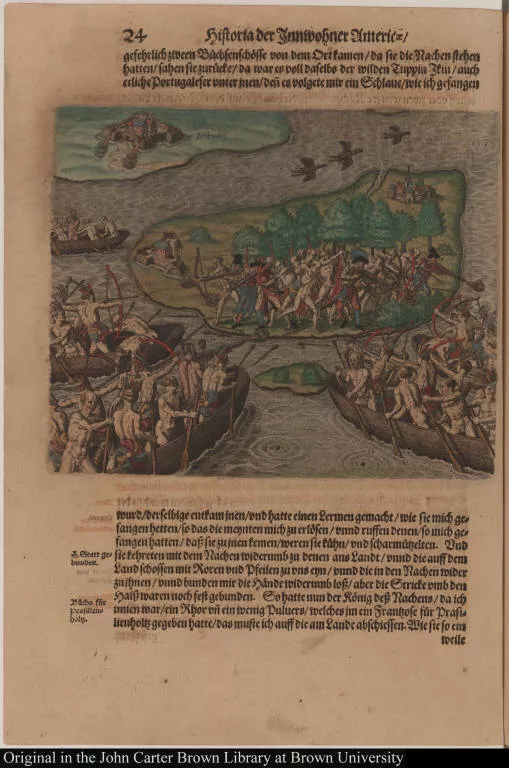

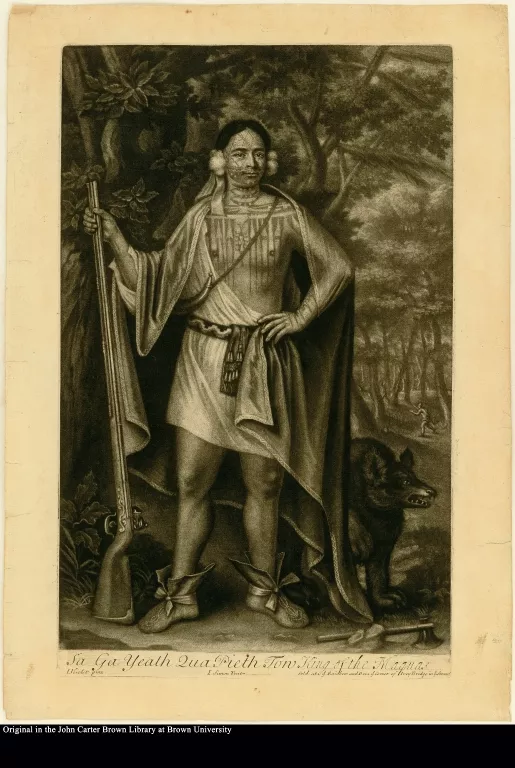

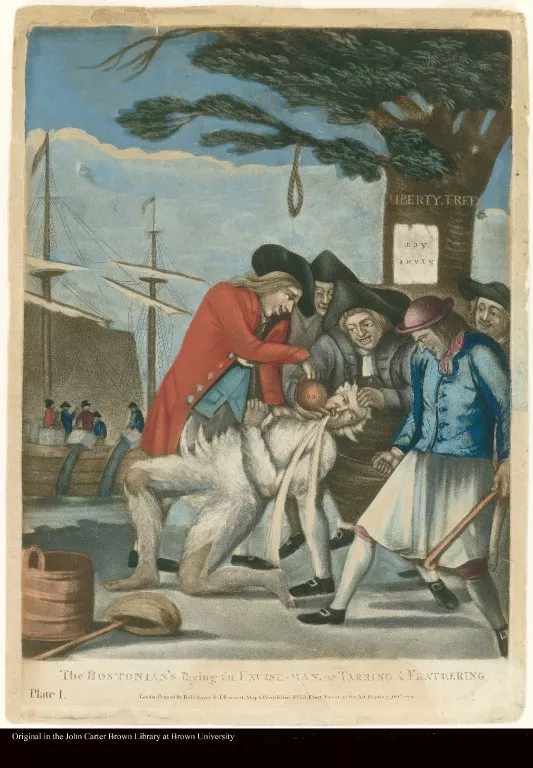

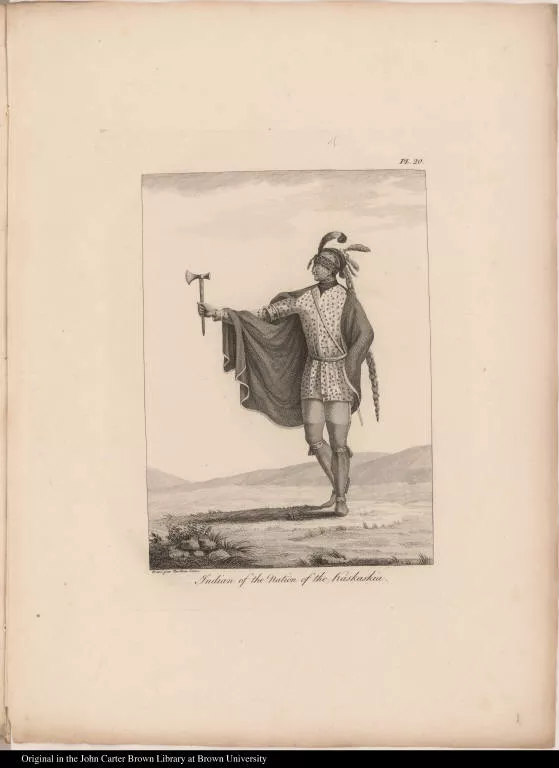

However, the native population was not always docile. When Columbus returned on his second voyage he dis¬ covered that the countrymen he had left behind had apparently been killed by those same Indians who had greeted them with such timidity on his arrival. In time, the Spanish began to differentiate between two tribes that inhabited the area, the gentle Arawaks and the aggressive Caribs. It has been suggested that this dis¬ tinction was not necessarily founded upon perceived ethnographic differences, but was instead based on the Amerindians reaction to the Spaniards— passive Indians were Arawaks, and hostile Indians were Caribs.

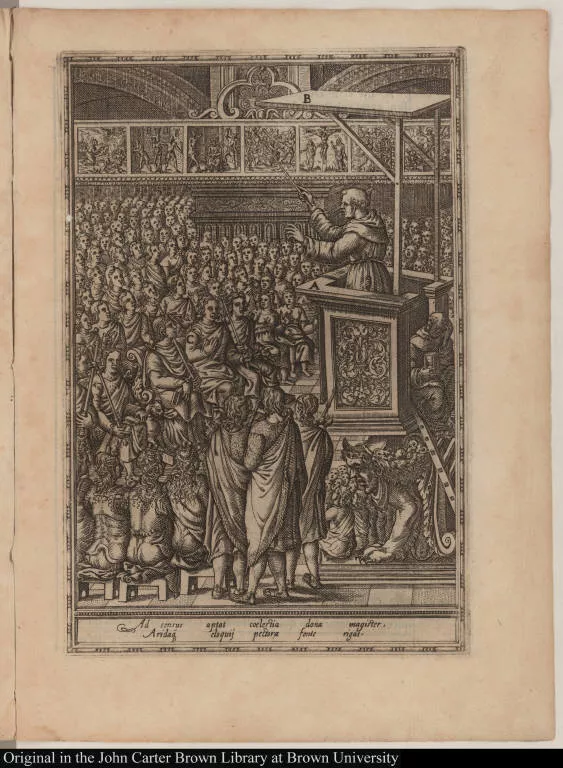

Of the ideological equipment that Europeans brought with them to America, religion was the most important. More than color or national sentiment, it was religion that made Europeans feel distinct from and superior to those peoples they met outside their own continent. Centuries of Christian crusades to free the Holy Land from the infidel had solidified this attitude and placed the question of religion uppermost in the minds of Europeans who came in contact with alien cultures. The Indians of America presented a special problem. Were they innocents, ripe for conversion, living in a Garden of Eden as before the Fall, or were they castaways of God ruled by the Devil? Matters of great practical importance concerning the treatment of the Indians hinged on the answers to these questions.

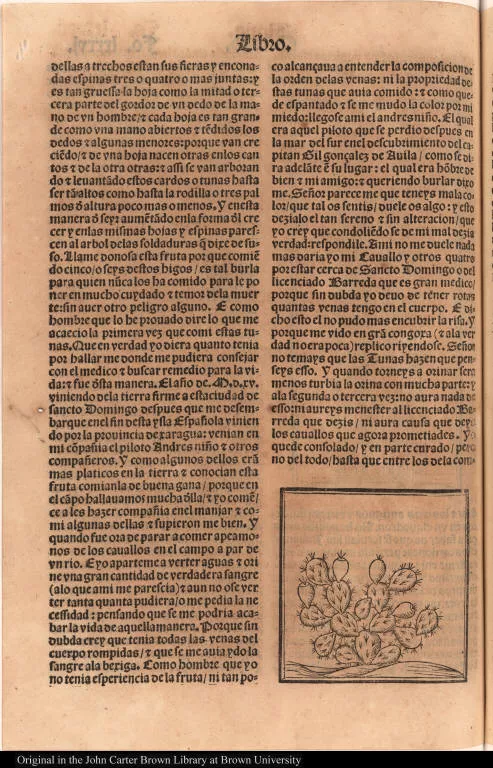

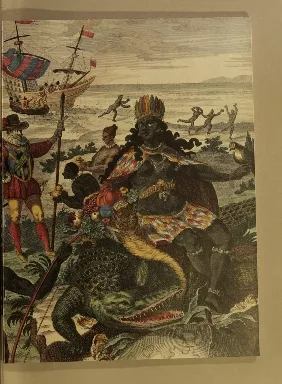

From long tradition Europeans accepted the existence of strange animals and bizarre semi-human creatures. As the boundaries of man’s “mental map” of his world were extended in this era of discovery, many of those monstrosities migrated west. Explorers told “true tales” of encounters with unusual peoples and animals, and while many of these stories were consciously embellished or invented, it is a fact that communication between newcomers and natives was rudimentary at best, giving rise to numerous possibilities for misunderstanding on both sides. Then, too, observations were often filtered through the screen of traditional European imagery, and many people saw what they expected to see.