I. The Beginnings: The Medieval Order

[The Wilczek-Brown Codex]

1440-1460

-

p. 1

p. 1The owner of this atlas, which was originally drawn in about 1450, has updated the map of Africa. With a swash of blue paint the news of Portuguese discoveries is recorded, obliterating the Ptolemaic conception of the original delineation.

(Item no. 6).

A Wider World

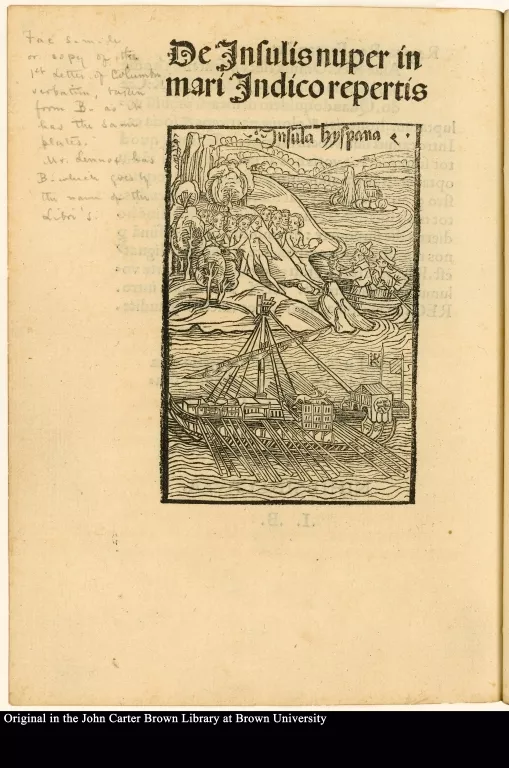

De Insulis nuper in mari Indico repertis

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1This illustrated printed announcement of Columbus's voyage, popularly called a “Columbus Letter,” shows the Discoverer landing on Guanahani in an oared galley.

It is thought that the woodcut may have seen previous service (without the Amerindians) as an illustration in a book depicting Mediterranean ports, for printing and illustration were not inexpensive processes and craftsmen often “made-do with what was on hand. Nevertheless, the picture presents the “idea” of landfall; the individuality of this event is expressed by the blockcutter’s addition of an unclothed native population.

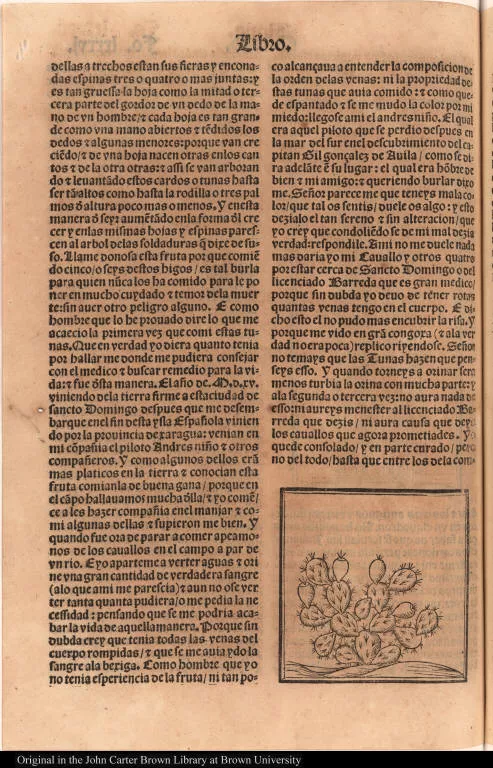

[Cactus]

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1These woodcuts of Indian huts are among the earliest pictures of buildings on the island of Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic) where Columbus established La Navidad, the first European settlement in the New World. Oviedo (who brought the first sugar plants from Spain to America) arrived in the West Indies in 1513 and served the New World Spanish empire in various administrative posts for thirty-four years.

Mit was Pomp die Königin vom König empfangen wirdt.

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1It is inaccurate to generalize about “American Indians” as though the Western Hemisphere contained only a single unified culture. Nevertheless, many early writers propagated stereotypes due to their ignorance of the diversity of New World peoples. If one tribe ate strange foods by European standards, the nature of all Indians was brought into question.

Certain elements in the Amerindian diet raised the suspicion that they were in association with devils, a natural consequence of the belief that one acquired the characteristics of the food one ate. This seemed to be indicated by the fact that many native peoples consumed snakes, lizards, toads, grubs, insects, and other “filth.” With horrified fascination it was noted that Amerindians “esteem serpents as we do capons,” and that serpents were eaten instead of bread.

Uslegung der Mercarthen oder Cartha marina

-

p. 36

p. 36Cannibals, called anthropophagi in Classical texts, were traditionally located at the edge of the habitable world. Although some real cannibalism did exist in certain areas of the Americas (for purposes and with meanings that are very difficult to interpret), the reality often merged with the old legends.

The text below the illustration reads: The cannibals are hideous, horrible creatures, appear to be equipped with dogheads, ghastly to look at, and they dwell on an island discovered by Christophel Dauber [“Little Christopher Dove”, i.e., Christopher Columbus] in recent years.

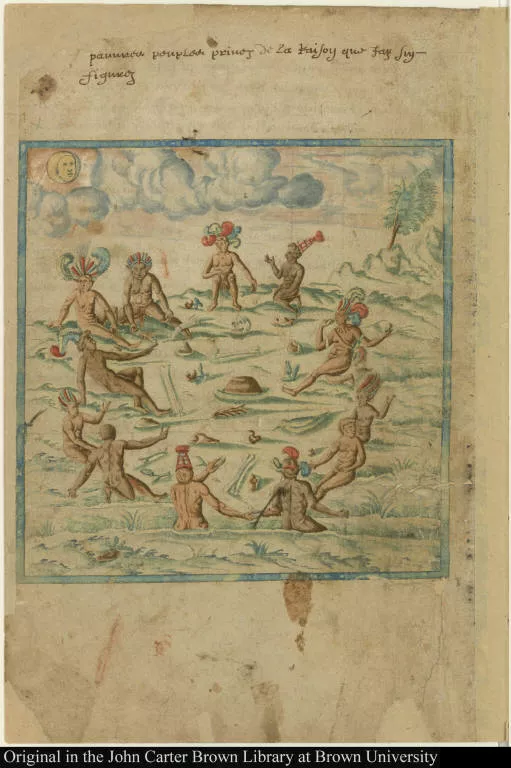

[Native American religious practices]

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1The author of this manuscript (attributed to Champlain) was a careful observer, but he sometimes became entangled in the preconceptions of a European bestiary that included all manner of imaginary creatures.

The figure shown here he described thus: “There are also dragons of strange figure, having the head approaching to that of an eagle, the wings like those of a bat, the body like a lizard, and only two rather large feet; the tail somewhat scaly, and it is as large as a sheep; they are not dangerous, and do no harm to anybody, though to see them, you would say the contrary.”

[The round-crested Duck.] Mergus.

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Explorers were especially impressed by the parrots of the West Indies and South America, which were larger and more brightly colored than the African species that were already known in the courts of Europe. Columbus mentioned these vividly colored birds in his “Letter” of 1493, and Brazil was characterized on many early maps as “the Land of Parrots.” Native featherwork was brought back to Europe, admired as much for the beauty of the plumage as for the intricacy of the finely worked designs.

America

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Here, the allegory of America joins European representations of the three continents of the Old World. America contains many of the elements one finds expressed in the written accounts of early explorers. The arrival of Columbus in the New World in search of wealth and converts is pictured on the left. “America” appears in the foreground as a dark-skinned, regal woman. Parrot in hand, enthroned upon an alligator, she offers the riches of the country to the new arrivals. The strange, exotic background evokes the sense of dream and wonder that permeated the accounts of early travelers.

The New World Emerges

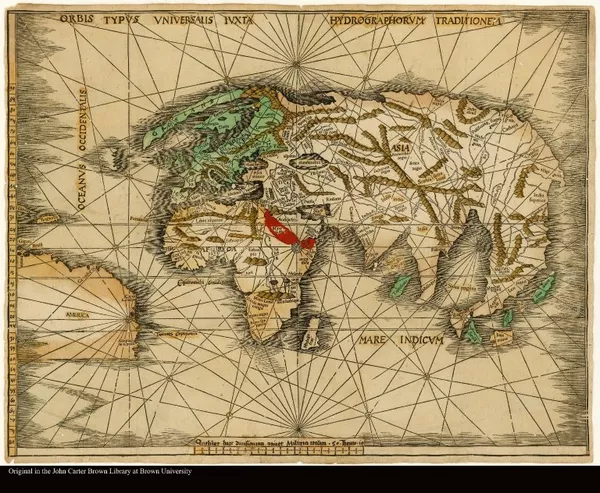

Orbis Typus Universalis Iuxta Hydrographorum Traditionem

1513

-

p. 1

p. 1The word “America” first appeared in 1507 in a pamphlet by the German cosmographer Martin Waldseemüller in which he suggested that the New World be named for Amerigo Vespucci—the other continents were named for women and it was only fitting that this one be named for the man who discovered it. Waldseemuller’s confusion about the priority of the discovery was due to Columbus having claimed only that he had found a new route to the East Indies, whereas Vespucci stated that he had set eyes on a new world.

This map, prepared about 15 07, is one of the very earliest to use the word “America.” It has been suggested that Waldseemüller later realized his mistake, for the name is no longer present on the map he drew in 1513.

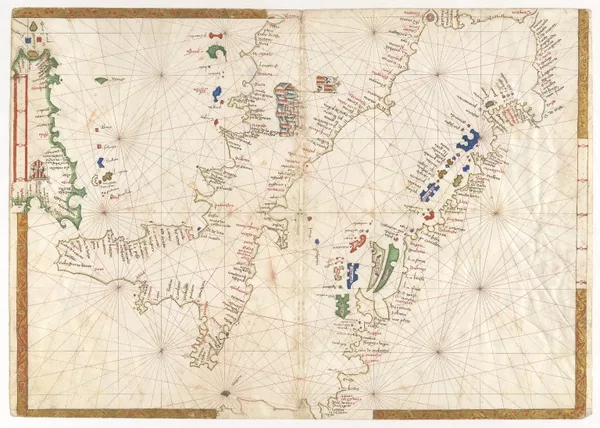

[Portolan chart of Italy as far as the mouth of the Tiber River, western...

-

p. 1

p. 1This world map is an important early depiction of European explorations in America. Maggiolo’s place names include “Lands found by Columbus,” “Land of the English,” and “Land of the Corte Real and of the King of Portugal.” Although the cartographer confronts certain geographical problems— North America is identified with eastern Asia—he avoids others, such as the exact configuration of the connection between the northern and southern continents of America.

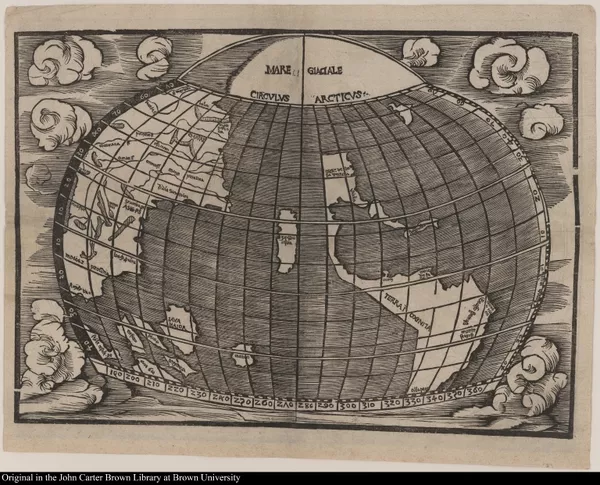

[Map of the western hemisphere]

1512

-

p. 1

p. 1This hemisphere, copied from the insets on a large wall map drawn by Martin Waldseemiiller in 1507, attempts to cope with perennial cartographic problems— the incorporation of new information into a standard body of accepted “truth,” and the consolidation of small-area sketches and verbal information into a broad picture of the world.

While the mapmaker presents a Columbian view of the discovery (America is an off-shore Asian landmass), he shows North and South America as having a continuous coastline—an inspired guess, since at that time no one had yet sailed along the entire coast.

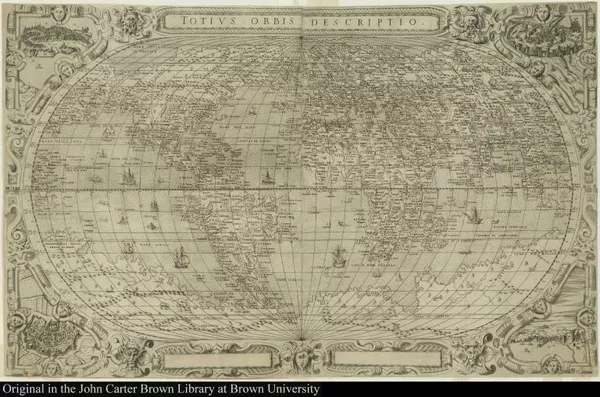

Totivs Orbis Descriptio.

1562

-

p. 1

p. 1For over two decades Giacomo Gastaldi was the leading mapmaker of Italy, both for his technical expertise in execution and for the information he assembled and interpreted. The maps shown here (both of which were in circulation during the same period of time) demonstrate the problems faced by the cartographer who had to reconcile often vague or contradictory information from many sources.

-

p. 1

p. 1One shows a narrow body of water, the “Streto di Anian,” between Asia and America...

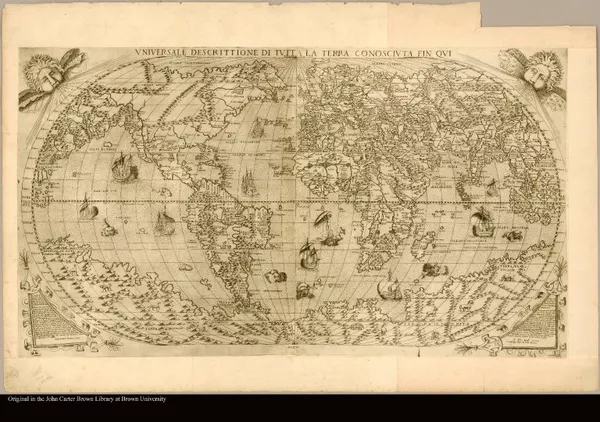

Vniversale Descrittione Di Tutta La Terra Conoscivta Fin Qui Paulo Forla...

1565

-

p. 1

p. 1... And one does not.

-

p. 1

p. 1The strait now named for Vitus Bering was not “discovered” until 1728, but Gastaldi had guessed its existence nearly two centuries earlier.

II. Expanding Horizons: The Wonders of Mexico

Newe Zeittung. Von dem Lande. Das die Sponier funden haben ym 1521. Iare...

1522

-

p. 15

p. 15It was reported that when the Spanish soldiers first saw the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan they said “it was like the enchantments they tell of in the legend of Amadis,” and that some asked “whether the things that we saw were not a dream.”

This woodcut, the first published view of that city (before its destruction by Cortés), looks like a medieval European town. It is an attempt on the part of the German illustrator to interpret written accounts, the only information available to him, of this “advanced civilization.” The faucet-like extensions from the city walls were an attempt to show the causeways that linked this “city in a lake” with the surrounding land.

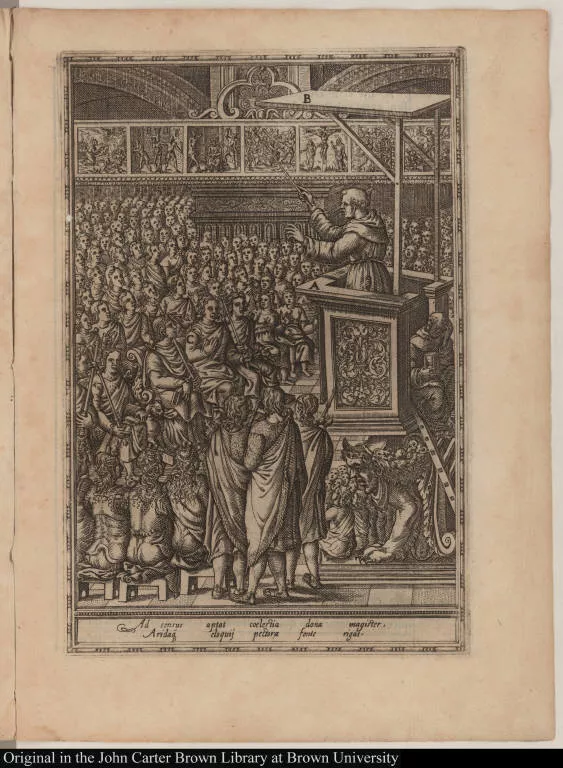

Ad sensus aptat coelestia dona magister, Aridaq eloquij pectora fonte rigat.

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1An Aztec temple is shown here as the center of activity for Mexican Indian civilization. Dancing, burial customs, cooking, astronomical observation, fishing, worship, and even human sacrifice are all represented in this composite view.

Praeclara Ferdina[n]di. Cortesii de noua maris oceani Hyspania narratio ...

1524

-

p. 115

p. 115This plan of Tenochtitlan as the conquistadors saw it, attributed to the artist Albrecht Dürer, is the earliest known map of an American city. It was sent to Spain and published in the first Latin edition of Cortés’s second “Relation,” or report, of 1524 in which he described his New World activities to the Spanish crown.

Tenochtitlan was completely destroyed by the Spanish in 1521 and Mexico City, designed by Cortés, was built upon its ruins.

This plan shows the city before its destruction: the principal temples of the Aztecs occupied the main square, causeways connected the city with the mainland, and an aqueduct supplied fresh water.

[The Virgin of Patrocinio with the four founders of Zacatecas]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1The illustration shown here is rich with the symbolism of Spanish conquest that would have been understandable to any reader of the day.

Four soldiers, two representing the Old World and two representing New World conquest, support the globe under the dominion of Philip II of Spain (“PLS II”). The sun at the left and the moon at the right signify that the sun never sets on the Spanish Empire. The bundles of arrows represent the kingdoms of Aragon, Navarre, Granada, and Castile, unified at the end of the fifteenth century. The shell represents St. Iago of Compostela (St. James), the patron saint of Spain during the reconquest of the Iberian peninsula. Tales of Spanish victories over incredibly superior forces of Indians led people to believe that St. James had also interceded on behalf of the Europeans in Mexico. The Virgin Mary protects and oversees the enterprise—with determined effort the entire world will become Christian under one prince. Labor Conquers All

8a Tozi que quiere dezir aguela. Diosas de los Mexicanos

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1In an attempt to extinguish idolatry, many Spanish missionaries made a concerted effort to remove all traces of native religious practices, which they accomplished all too well. With hindsight, however, the Church realized that in destroying the records of Aztec civilization they had also deprived themselves of a deeper understanding of that culture.

8a Tozi que quiere dezir aguela. Diosas de los Mexicanos

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1Without such information the clerics could not probe behind Indian “conversions of convenience” to uncover lingering remnants of paganism.

8a Tozi que quiere dezir aguela. Diosas de los Mexicanos

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1By the middle of the sixteenth century, some missionaries were actively encouraging Spanish- schooled Indians to record what they remembered of Aztec civilization. Juan de Tovar’s manuscript history is accompanied by watercolors that illustrate the native religion as it existed before the conquest. The paintings were possibly done by an Indian artist who was drawing on direct recollection of destroyed works.

South America Revealed

[Early representation of Newfoundland, Lower California, the Amazon, and...

1545

-

p. 1

p. 1This is one of the earliest maps to show the results of Spanish exploration of the interior of North and South America. On the continent of South America is recorded Francisco de Orellana’s great trek between 1539 and 1542.

Starting at Quito, Orellana traveled across the Andes to the headwaters of the Amazon and down that great river to its mouth. Originally in three parts, this map has been attributed to Antonio Pereira, a Portuguese seaman. The other two sections have not, as yet, been found.

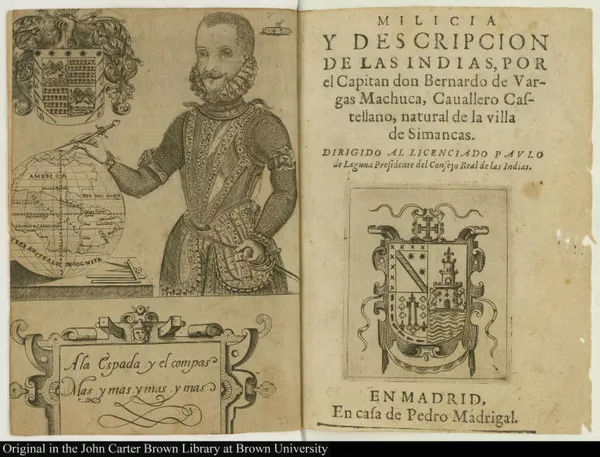

A la Espada y el compas Mas y mas y mas y mas

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1With his left hand resting on his sword and his right on a compass that divides the world, this conquistador exemplifies the idea that there is no limit to Spanish possibilities in the New World. “With the sword and the compass, more and more and more and more” is its message.

The book it introduces is a practical, “how-to” manual for the would-be conqueror written by a soldier with many years of experience in America.

Lowland Rainforests and Andean Riches

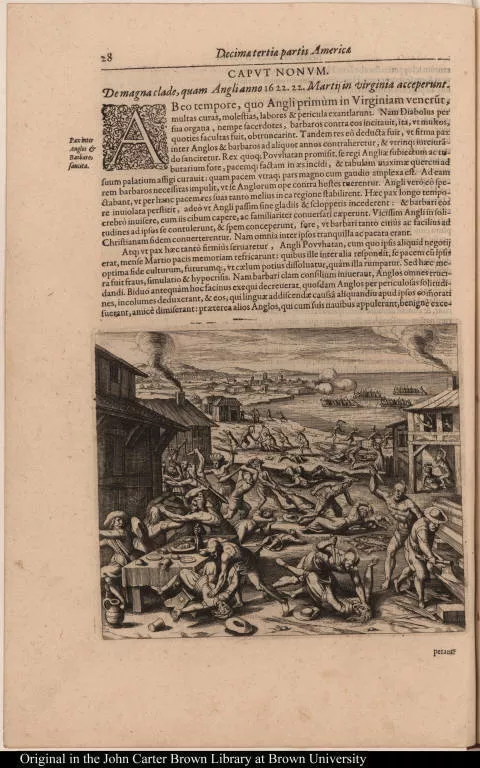

[De magna clade, quam Angli anno 1622. 22. Martiij in virginia acceperunt.]

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1The land and the beasts that inhabited it took on an almost malevolent character as explorers battled their way through a country that seemed unfit for “human habitation and far away indeed from the civilized world.

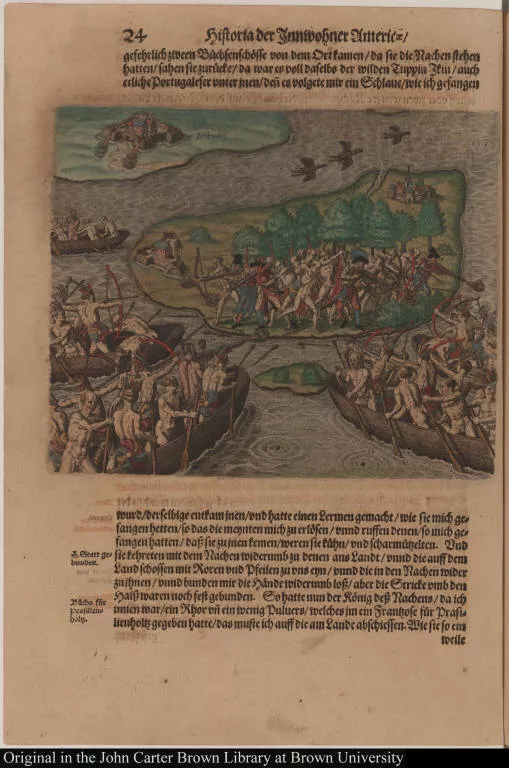

[How the savages, having captured me, fought our people who attempted to...

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1Tales of cannibalistic tribes quickly caught the European imagination, but even contemporary observers criticized the tendency to show Amerindians in the midst of hanging human parts as if they were in a butcher shop, stating that the artists had never seen what they were trying to depict.

Nevertheless, the pictures circulated widely and served to emphasize the strangeness of the world opening up across the Atlantic Ocean.

Histoire d'un voyage fait en la terre du Bresil, autrement dite Amerique

1594

-

p. 251

p. 251War is one of the most complex of human institutions, with particular characteristics that vary from culture to culture. European observers usually had little comprehension of Amerindian tribal war, which often was highly ritualized and fought for limited ends.

Louis Marie.

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1A “before and after” picture of Christian conversion. Native Americans were taken back to Europe on a regular basis beginning with Columbus, not always voluntarily. Shown here are members of an Indian delegation from the coast of Brazil brought to Paris in 1613, when the French were attempting to establish a colony in what was considered Portuguese territory and sought to forge an alliance with the local population.

Louis Marie.

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1Some members of the delegation sickened and died in France. Those who survived were baptized and given Christian names.

Mariae Sibillae Merian Dissertatio de generatione et metamorphosibus ins...

1719

-

p. 218

p. 218In 1699 Maria Merian and her daughter traveled unaccompanied to Surinam, where she concentrated on painting the indigenous plant and insect life. Merian’s accuracy, technical expertise, and vibrant artistic skill, along with her noteworthy research in natural history, earned her a solid reputation in scientific circles.

-

p. 17

p. 17Columbus first encountered the pineapple on his second voyage to America in 1493. Its reception in Europe was enthusiastic: “The fruit of the pine-apple... undoubtedly surpasses all the fruits with which the world is at present acquainted.”

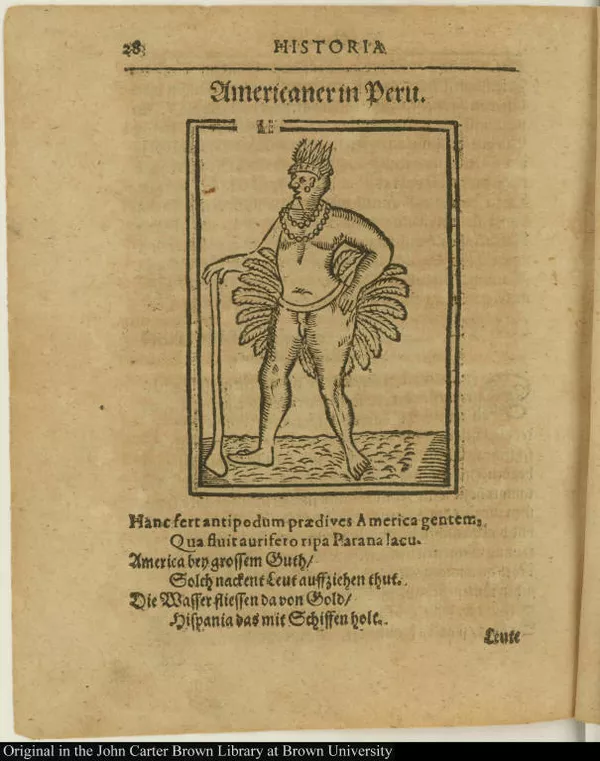

Americaner in Peru.

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1Depicted here is a Peruvian Indian. The poem in German below the image states that although the people of the country are naked, its rivers flow with gold, which Spain carries away in the holds of her ships.

Prima Columbi in Indiam navigatio. Anno 1492.

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1In retribution for Spanish greed, Amerindians are shown obliging the invaders’ craving for gold by pouring the molten metal down their throats.

Americae pars sexta

1596

-

p. 7

p. 7Theodor De Bry’s view of Indians working in the mines.

III. The Lure of North America: Impressions of Natural Bounty

A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia

1590

-

p. 71

p. 71Some ordinary Amerindian customs struck the newcomers as strange enough to require special comment. The “odd” way that women carried their children is described in detail...

-

p. 85

p. 85... As is the “barbarous” custom of sitting on the ground to eat.

In this illustration from De Bry, the engraver has altered the position of the legs shown in John White’s original drawing to one more “comfortable” by European standards.

Resources, Development and Trade

The herball or Generall historie of plantes

1597

-

p. 807

p. 807This is the first published picture of the white potato (as distinguished from the sweet potato, also of American origin), a plant that eventually became a staple in European diets.

In 1585 one variety of potato was brought to England by Sir Francis Drake, who had encountered the tubers in his raids on Spanish outposts in Panama.

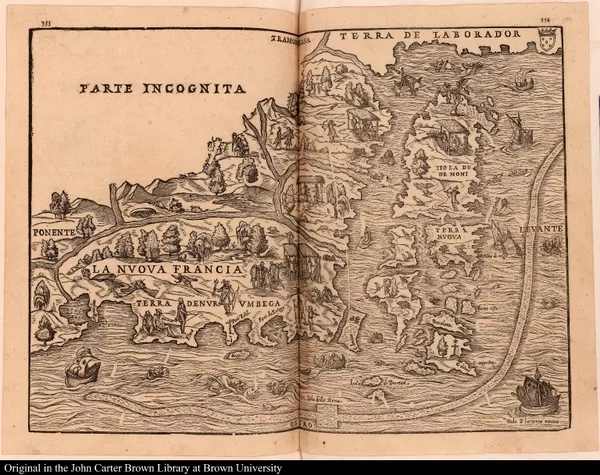

La Nuova Francia

1606

-

p. 1

p. 1“If maize were the only gift the American Indian ever presented to the world,” it has been said, “he would deserve undying gratitude,” for it has become one of the most important foods for men and livestock. By the end of the seventeenth century, it was widely grown as a staple in Spain, France, Italy, and in Africa.

However maize was introduced to most Europeans by the Turks after its spread east across the African coast of the Mediterranean and was commonly called “Turkey” or “Turkish” wheat.

[Toda la tierra de las Indias] [Toda la tierra del mundo viejo y sabido]

1553

-

p. 1

p. 1No animal of North America made a more profound impression on Spanish explorers than the bison. Totally unknown to Europeans, they were found in huge herds on the great plains between the Mississippi and the Rio Grande.

Descriptions by the chroniclers of some of the early Spanish expeditions are vivid: “and they have between the two Horns an ugly Bush of Hair, which falls upon their Eyes, and makes them look horrid.”

[left] Armadilho. [right] Pece Muger, sive piscis [andropomorphus]

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1Medicinal uses were found for both real and imaginary animals. The bones of the armadillo’s tail were ground into a powder and used as a painkiller; some claimed that deafness could be cured as well.

This mermaid (“pece muger,” or “pesci donne”) from the coast of Brazil reportedly had “tender bones, which [when used in the proper manner] promote chastity, inhibit carnal desires, render men impotent, and are useful in many other ways for the good of the body.”

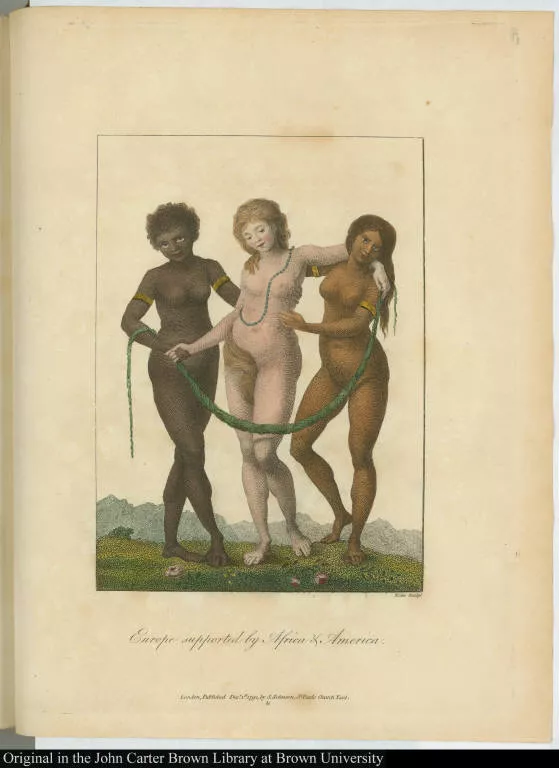

Europe supported by Africa & America.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1This illustration, by the English poet and artist William Blake, shows “White” Europe supported by the resources of “Black” Africa and “Indian” America. Vast amounts of labor were required to ensure that the wealth of the New World flowed regularly and in ever-increasing amounts back to the homeland.

Americae pars quarta. Sive, Insignis & admiranda historia de reperta pri...

1594

-

p. 213

p. 213Early in their occupation the Spaniards had to face the fact that Indians were difficult to enslave. Among other problems, it was too easy for them to escape back into their surrounding societies.

Moreover, the goodwill of Indian tribes was often a necessity for the Europeans’ survival. The Spanish looked to Africa to solve the labor shortage, and the Atlantic slave trade began, in which the Dutch, French, Portuguese, and English were also active participants.

In the tradition of the “Black Legend” of Spanish cruelty in the New World, this illustration shows Amerindians committing suicide rather than face enslavement by the Spanish.

[Native American religious practices]

1601-1650

-

p. 1

p. 1Although this manuscript account of a voyage to the Spanish west Indies in 1599, attributed to Samuel de Champlain, focuses mainly upon the indigenous flora and fauna, the author gives some information about the lot of the Indians under Spanish rule.

According to him, the harshness of the Inquisition caused the Indians to flee to the hills. The Spaniards who followed them were captured and eaten. At the time of this writing the situation had eased somewhat, and the author states that had the Spaniards continued still to chastise the Indians according to the rigor of the Inquisition, they would all have died by fire.

Americae pars quinta

1595

-

p. 11

p. 11From its fifteenth-century beginnings with the establishment of Portuguese trading posts on the west coast of Africa, the Atlantic trade in African slaves spread quickly throughout the American colonies.

Slavery itself was an age-old, world-wide institution, and the particular forms it took in the colonization of America were due to a variety of factors. One thing is certain, the demand for labor to produce sugar, tobacco, silver, and other commodities was great, and slaves brought from Africa supplied most of it.

Reduced to a commodity, slaves were truly “faceless” people, depicted as part of the furniture of colonial life.

They typically figured in illustrations of the time in much the same way that tools might appear in a farmyard scene.

[Winding silk from the cocoons]

1601-1650

-

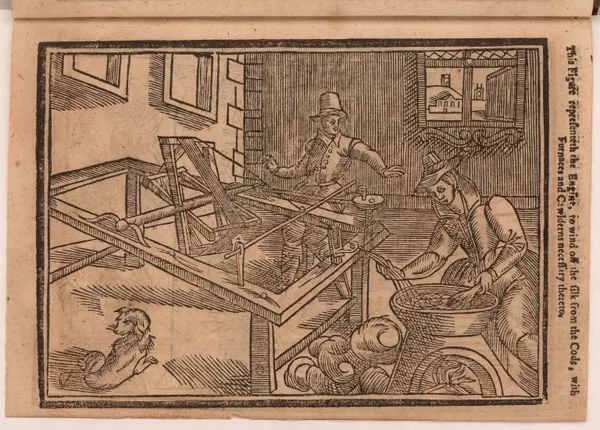

p. 1

p. 1Denied easy access to Asia, the English attempted to establish a silk industry in Virginia. The colonists greatly underestimated the difficulty of the process, however, and at first misunderstood even the kind of mulberry leaf the silk worms fed upon. Despite high hopes, hardly any silk was ever produced in colonial Virginia.

[Native American paddling a kayak]

1651-1700

-

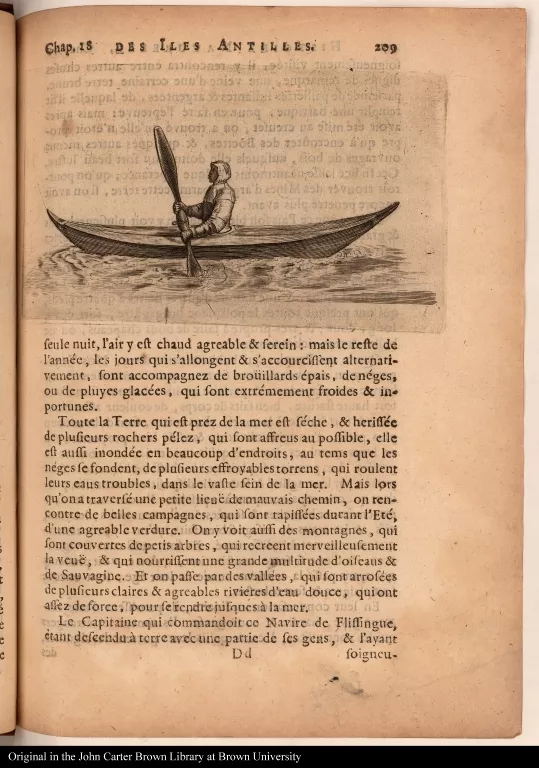

p. 1

p. 1The author of this book was a Huguenot who actively encouraged French Protestants to settle in America.

Shown here is the apocryphal city of Melilot, capital of the Indian kingdom of Apalache.

Although usually assigned a location in present-day Florida, it was sometimes placed in Georgia. According to Rochefort, the kingdom was home to a mysterious band of European Protestants who had been driven from their Virginia colony.

This is probably the first printed illustration of a North American utopian city.

Der ander Theil, der newlich erfundenen Landtschafft Americae, von dreye...

1591-1603

-

p. 77

p. 77A meeting between Frenchmen and Florida Indians in 1564 is depicted here with a European court atmosphere.

The French brought ready-made marker columns with them to be used in establishing their claims to New World territory. The Indian “king,” Athore, shows the French commander, Rene de Laudonniere, a column left by the leader of an earlier reconnaissance mission in 1562.

Misunderstanding its significance, the Indians have treated it as an idol and have brought tribute to honor the place. The gestures of the worshippers are European, however, rather than Amerindian.

[Allegorical image of America]

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1The poem engraved on the verso of this print makes it obvious that the cannibal image symbolizes not only the Amerindians, but also the malevolent aspects of the land itself.

IV. Settlement brings Conflict: Conflicts of Culture

A Birch canoe pol'd amongst Rocks & Stones agst. a Rapid Stream

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1The native American population in the north allowed game to roam freely, practiced companion planting of maize and beans, and did not use the same planting area year after year. From the first, however, English settlers cleared the land and fenced their property in accordance with European custom.

These practices permanently (and almost immediately) changed the landscape that had so impressed the colonists upon their arrival and were directly responsible for many confrontations between the newcomers and the Indians.

Newes from America; or, A new and experimentall discoverie of New England

1638

-

p. 9

p. 9In the opinion of political leaders in Massachusetts and Connecticut, the Pequot tribe was an undesirable neighbor.

This battle plan depicts an attack that took place in 1637 on a fortified Pequot village in Mystic, Connecticut, by the English and their Narragansett Indian allies. English soldiers with firearms were arranged around the inner circle, while the Narragansetts with bows and arrows occupied the outer circle. The desperate Pequots tried unsuccessfully to break through the lines in order to avoid certain annihilation.

The Narragansetts were so horrified by the ferocity of the English attack, which included the slaughter of women and children (less than five out of 500 escaped), that they withdrew in shame.

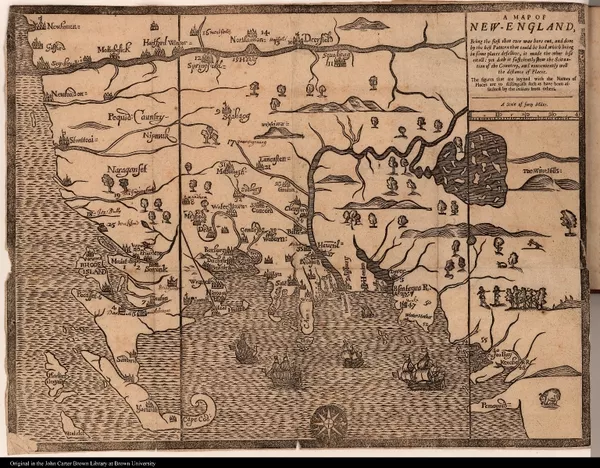

A Map of New-England, Being the first that ever was here cut ...

1677

-

p. 1

p. 1This map, the first to be drawn, cut, and printed in America, is a “news map” keyed by number to show the battles of King Philip’s War.

The map is oriented with north at the right. Shown here is the earliest, or “White Hills,” version. When it was copied in London later that same year, the woodcutter mistakenly identified the mountains at the right as the “Wine Hills.”

Conflicts of Empire: Challenges to Spain

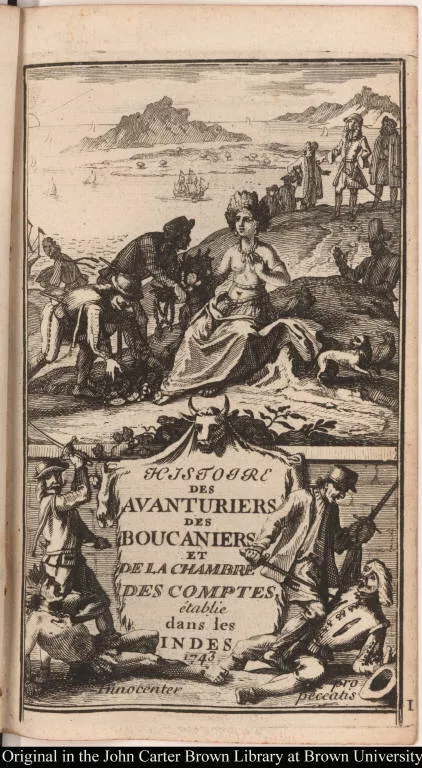

[Title page]

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Buccaneers (who were often the human debris of earlier expeditions to America) hunted the wild cattle that had multiplied unchecked since the mid-sixteenth century when large numbers of Spaniards abandoned their island plantations to search for treasure in Mexico and Peru.

These men were superb marksmen, an advantage when they joined together to harass Spanish shipping.

Here, a pipe-smoking buccaneer and his dog pause before his village on their return from a hunt.

S. Augustini pars est terrae Florida ...

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1This is the earliest known view of St. Augustine, the first permanent European settlement in what is now the United States. It was established in 1565 by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés as a base of operations to guard Spanish interests in the Caribbean and to eradicate the French Huguenot presence in “Florida.”

In this last charge Menéndez was successful: the French settlement was destroyed and the colonists were massacred. It is reported that he placed the following inscription on the site: “I do this not to Frenchmen, but to heretics.”

In 1586 Sir Francis Drake burned the town and fort of St. Augustine, and this illustration was published to accompany the account of his raids on Spanish America. The fish at the lower left is supposed to be a dolphin.

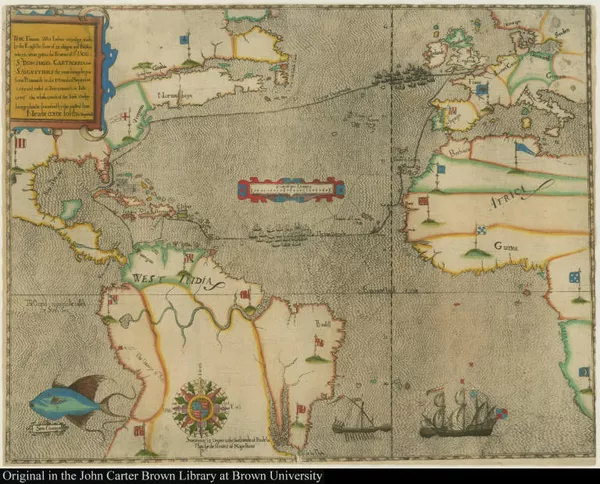

The Famouse West Indian voyadge made by the Englishe fleete of 23 shippe...

1589

-

p. 1

p. 1Justice-seeking and recompense for Spanish ill-treatment of Englishmen were the stated purposes of Sir Francis Drake’s depredations on Spain’s New World empire. Success at capturing Spanish and Portuguese although his expeditions were often beset with problems—by accident of timing, cities yielded no ransom, cornered prey eluded his grasp, and treasure slipped through his fingers. Drake was a great sailor, however, and the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe. His daring elevated him to the status of hero.

This map traces Drake’s route from the Cape Verde Islands to Santo Domingo, Cartagena, and St. Augustine in an expedition undertaken against the Spanish in 1585. On the way home, his fleet stopped at Virginia to check on English colonists put ashore ten months before.

Vying for North America

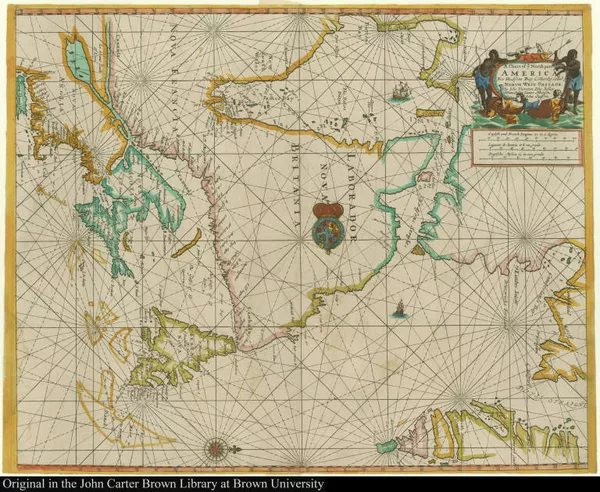

A Chart of ye North part of America For Hudsons Bay Com[m]only called ye...

1677

-

p. 1

p. 1Decorative, generalized maps may have served the needs of armchair travelers, but colonial administrators needed more precise information for the business of government and often contracted with local surveyors to produce accurate reconnaissance maps.

This English manuscript map of Long Island, its shape determined by the animal skin upon which it was drawn, is impressive for its beauty as well as for its accuracy. Based upon a draft of the first extensive survey of the area, it was used by English administrators after the defeat of the Dutch in 1673.

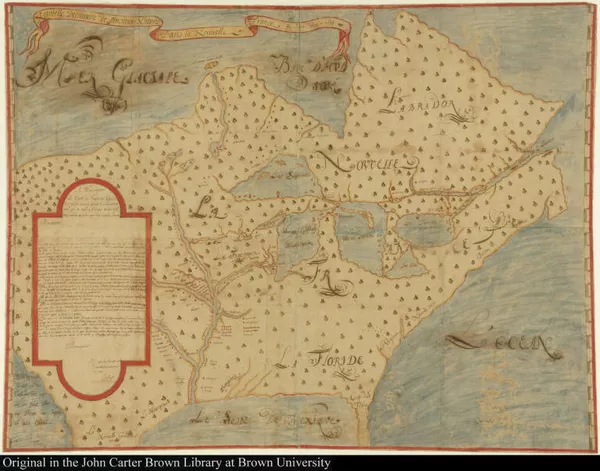

Nouvelle Decouverte de plusieurs Nations Dans la Nouvelle France en l'an...

1674

-

p. 1

p. 1In 1673 the French fur trader Louis Joliet and Father Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit missionary, explored the Mississippi River, but records they kept of their trip were lost in a canoe accident. Upon his return to Quebec, Joliet drew a map from memory and the manuscript shown here is one of several copies that were made at the time.

This is one of the earliest representations of the course of the Mississippi. Away from the areas actually traversed by Joliet, however, it is a fairly poor geographical view. Among other things, the map shows the locations of various Indian nations, information that was of vital interest to French traders and missionaries.

In the cartouche at the left is a copy of a letter to the governor of New France, Comte Frontenac, in which Joliet alludes to the fertility of the country. He also states that the Missouri River leads to California and the Pacific, a convenient (but nonexistent) water route to the riches of the Orient.

Quebec, The Capital of New-France, a Bishoprick, and Seat of the Soverain Court.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1There are very few views that portray Quebec between its founding in 1608 and the English siege by General Wolfe in 1759. This latter event, however, occasioned many commemorative and “news views.” The siege of Quebec was of great interest to English colonists in the north—Bostonians had participated in the military action, for New France was close enough to be perceived as a direct threat.

This print, by the Boston engraver Thomas Johnston, is the earliest American engraved view of Quebec. Although the advertiser proclaimed that it was done “from the latest and most authentic French original,” it is actually based on an inset from a French map published forty years earlier.

Carte des possessions Françoises et Angloises dans le Canada et partie ...

1756

-

p. 1

p. 1The French view of North America.

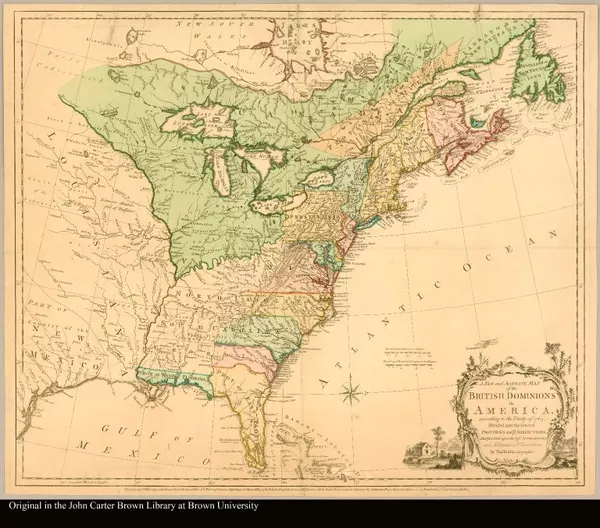

A new and accurate map of the British dominions in America, according to...

1764

-

p. 1

p. 1The English view of North America.

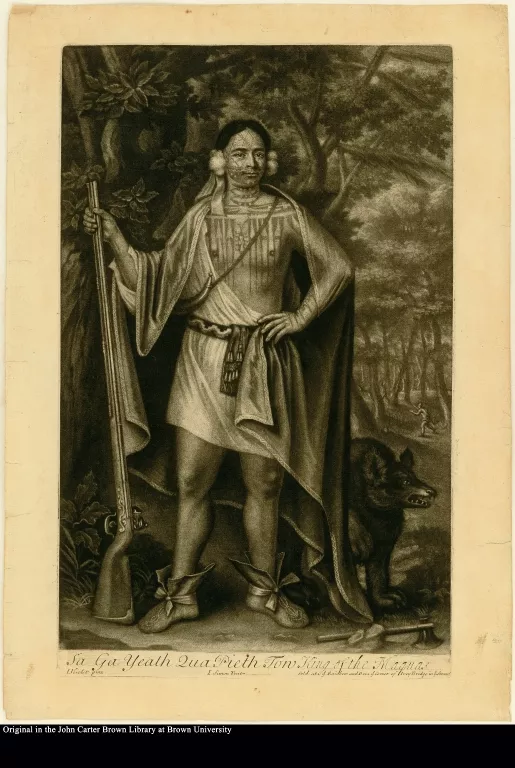

Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Ton King of the Maquas

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, baptized Brant, is identified as a great hunter. The scene behind him recalls his offer to Queen Anne to run a deer to death. Brant died shortly after his return to America, but his grandson, Joseph Brant, came to London in 1776.

The brave old Hendrick the great Sachem or Chief of the Mohawk Indians, ...

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1The Emperor of the Six Nations, baptized Hendrick, had a long association with the English. Hendrick headed the delegation to London in 1710 and, on his return thirty years later, was presented with an elaborate suit trimmed in lace.

He is shown here as he was painted in this finery, which was passed on to his son after his death (as an ally of the English) at Lake George in 1775.

V. Europeans Become Americans: Settling In

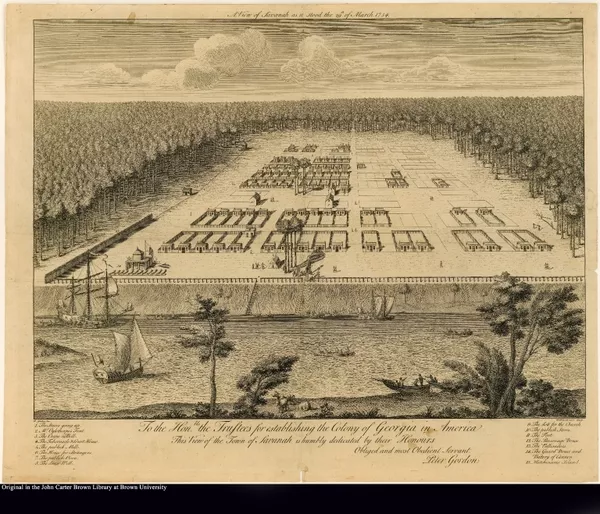

A View of Savannah as it stood the 29th of March. 1734

1701-1750

-

p. 1

p. 1James Oglethorpe, the English philanthropist who founded Georgia, chose the site and laid out the city of Savannah in 1733. Intended as a refuge for debtors, Georgia was also designed to be a buffer colony against the Spanish in Florida.

The original plan called for a number of wards, each consisting of forty house lots. Fronting the square on two sides were lots set aside for churches, stores, and other public uses.

Here, Savannah is shown in its earliest days, being carved out of the wilderness. Ten years later there were about 350 houses, many of which were considered “large and handsome".

A South West View of the City of New York in North America. Vue du Sud O...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1This picture of New York was drawn about 1764 by Captain Howdell at a site near the East River presently occupied by public housing projects.

The particular view of lower Manhattan chosen by the artist is now obstructed by the FDR Drive and the approaches to the Manhattan Bridge.

A South-East View of the City of Boston in North America.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1This print of Boston harbor was based upon a view by William Burgis drawn about 1722.

Breaking Away

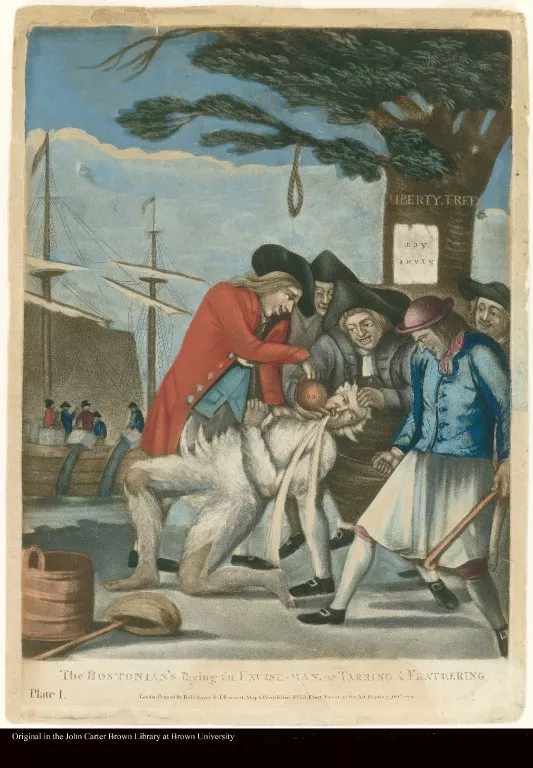

THE BOSTONIAN'S Paying the EXCISE-MAN, or TARRING & FEATHERING [BOSTONIA...

1774

-

p. 1

p. 1The Liberty Tree provides a backdrop for this popular satire depicting the brutal treatment meted out to John Malcomb, Commissioner of Customs, for attempting to collect duty in Boston.

Malcomb was tarred and feathered, made to drink enormous quantities of tea, and threatened with hanging.

An Exact View of The Late Battle at Charlestown June 17th, 1775.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Bernard Romans—civil engineer, naturalist, cartographer, and historian—was responsible for an important group of maps of the Revolutionary period.

In 1774 and 1775 he was in Boston and engraved this eyewitness account of the Battle of Bunker Hill showing the towns of Boston and Charlestown.

The outcome of the battle was of interest to a European audience and this view was re-engraved in England for British circulation in the following year.

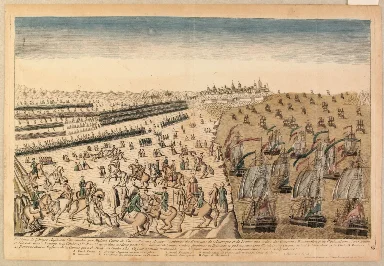

Reddition de l'armée angloises commandée par mylord comte de Cornwalli...

1781

-

p. 1

p. 1On October 19, 1781, Cornwallis surrendered with 7,000 men. This print was intended to be used with a vue d’optique.

Vuë de la Nouvelle Yorck. Neu Yorck. Eine Stadt in Nord-America auf eine...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Many optical views of American towns, such as these, were adapted from pictures of European cities. Nevertheless, their wide circulation transmitted an image of urban America to a vast audience eager for news. They can best be appreciated, perhaps, as a contemporary manifestation of the earlier tendency to “make do” with the “idea” of a place rather than with an accurate description.

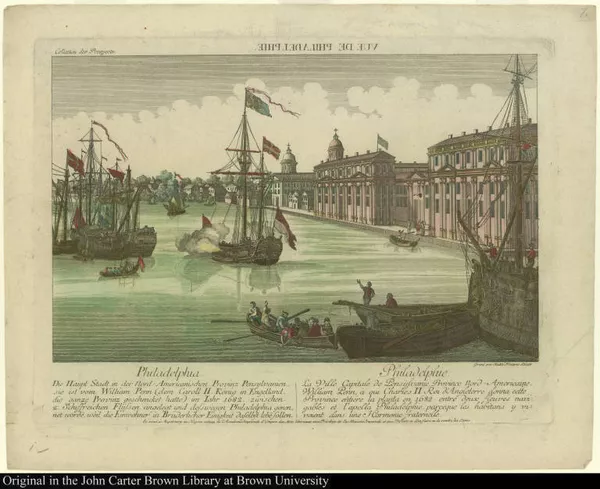

Vuë de Philadelphie. Philadelphia. Die haupt Stadt in der Nord-Americans...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Although these prints claim to depict New York and Philadelphia, they are actually copies of an engraving of Deptford, England—one half of the original serves as New York, the other half as Philadelphia.

The Promise of America

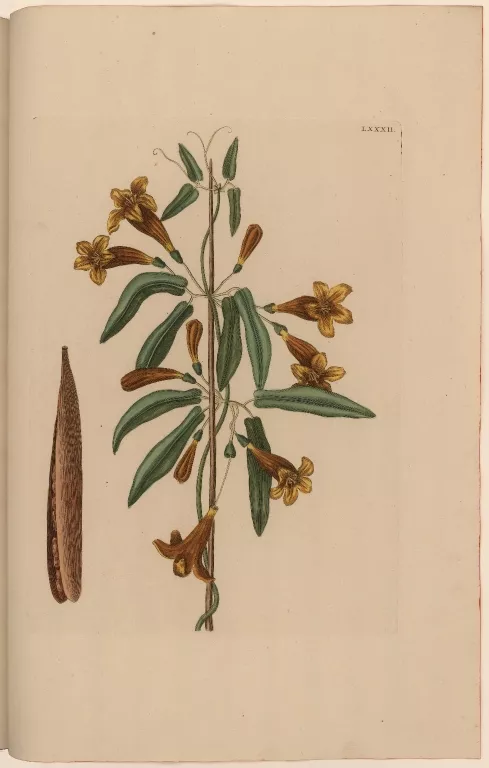

[The crossvine]

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Mark Catesby, an eighteenth-century English naturalist and traveler, strove to provide a complete and accurate visual record of the flora and fauna of the southeast of North America and the Bahamas.

The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands

1731-1743

-

p. 1

p. 1In a remarkable tour de force, Catesby single-handedly observed, drew, engraved, and finally published his observations in two folio volumes, with some two hundred plates. He was the first to paint North American birds in their natural settings.

Mount Vernon in Virginia The Seat of the late Lieut: General George Wash...

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1A view of Mount Vernon, the earliest engraving of Washington’s home to be sold in Great Britain.

A Display of the United States of America

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Six times during Washington's term as President, Doolittle issued a version of this patriotic display, periodically bringing the names of states and territories and their statistics up to date.

This, the first state of the engraving, shows Washington in civilian dress; beginning with the second state of 1790, all the others show him in military uniform.

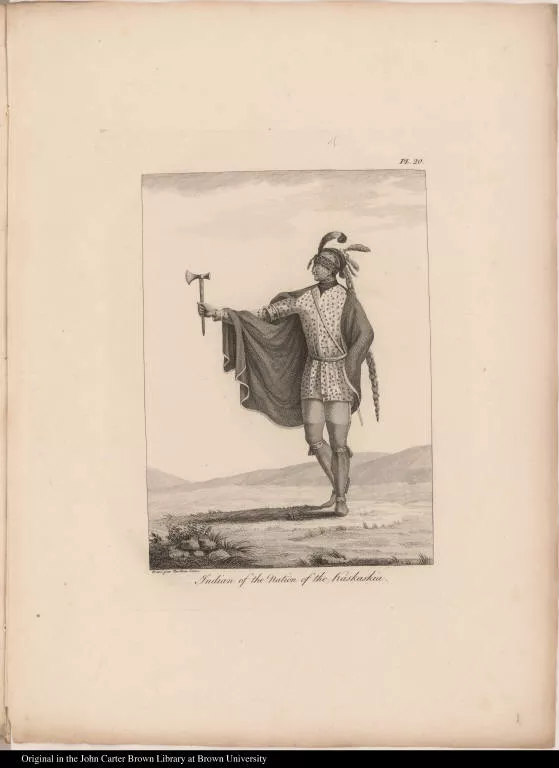

Indian of the Nation of the Kaskaskia.

1801-1850

-

p. 1

p. 1General Victor Collot fought under Rochambeau during the Revolution and later became governor of Guadeloupe. In 1796 he returned to North America to survey the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers for the French government. Before his death in 1805 the account of his expedition and an accompanying atlas of maps and plates had been printed, but the unbound sheets were suppressed for political reasons and were not offered for sale until 1826.

Shown here is Collot’s view of an American log cabin.

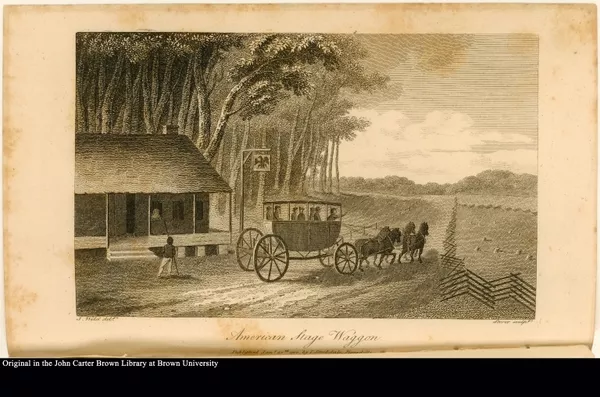

American Stage Waggon

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Isaac Weld sailed from Dublin to see if America offered a happier alternative to Europe, and after two years of travel, decided that it did not.

Weld describes a stagecoach: “The coachee is a carriage peculiar, I believe, to America; the body of it is rather longer than a coach but of the same shape. In the front it is left quite open down to the bottom, and the driver sits on a bench under the roof of the carriage. There are two seats in it for the passengers, who sit with their faces towards the horses.”

Plan of the City of Washington in the territory of Columbia ceded by the...

1792

-

p. 1

p. 1A major cartographic activity during the last decade of the eighteenth century was the mapping of states and cities.

The city of Washington, D. C., was designed by the engineer and architect Pierre Charles L’Enfant, who refused to release a map for fear of land speculation.

Andrew Ellicott, an assistant to L’Enfant, drew the first official plan of the city, which was published in 1792.

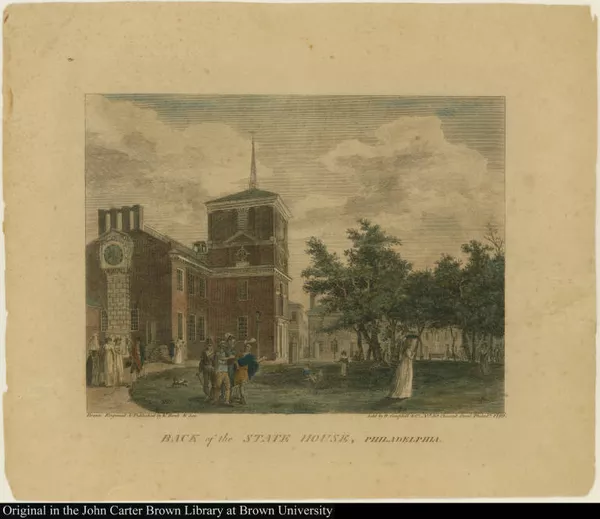

Back of the State House, Philadelphia.

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1The Birch views of Philadelphia provide visual documentation of the beginnings of an American way of life. John Birch executed twenty-eight views of Philadelphia with the intention of recording a complete cross-section of the city that at the time represented the zenith of American culture and achievement. He reviewed both public and private buildings and also included details of street life that had not yet been portrayed in America. A sense of accomplishment and pride is reflected in these images of the American city.

Emblem of America

1800

-

p. 1

p. 1At the close of the eighteenth century “America” receives a Classical presentation, visual evidence of the anticipated success of the “noble experiment” of American democracy— Reason is in harmony with Nature.

Original Catalogue

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library