1. The Discovery of Discovery

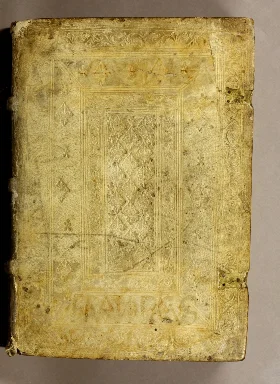

Marco Polo Venetiano

1555

-

p. 1

p. 1The Venetian merchant Marco Polo went to China in 1271. The tale of his travels was rich in detail, shrewd in judgment, filled with stories of adventure, danger, and wealth. While Marco Polo shared the outlook and skills of his class, his experiences resembled those in tales of chivalry. Many Venetians found the wonders he described to be beyond belief: the distances he traveled were greater than the extent of the whole world known or imagined at the time; the peoples he described were not described by anyone else; the wealth he encountered surpassed imagination. His book was called II Milione because there were so many superlatives in it. But the book was enormously popular; nearly 200 copies of the manuscript survive.

When travel to China turned out to be but an interlude—early in the fourteenth century the rising power of the Tartars in Central Asia created a barrier through which no European could safely enter—Marco Polo’s vivid stories kept alive the memory of China and stimulated later explorers to seek a route to Cathay.

jcb (3)1:189; Sabin 44498; Leonardo Olschki, The Genius of Italy, Oxford, 1949, p- 37 °; Marco Polo, The Description of the World, edited by A. C. Moule and Paul Pelliot, 2 volumes, London, 1938.

Acquired after 1865, before 1875, by John Carter Brown.

With the closing of the routes to China, Europe—bounded to the south and east by the aggressive, imperialistic forces of Islam—was placed on the defensive and confined to an area which was continually shrinking. To the west lay the inhospitable Atlantic. During the fifteenth century, by mastering the ways of sailing ships across the ocean, Europeans transformed the Atlantic from a barrier to a highway. In doing so they gained an initiative in the world arena which has lasted through this century.

Prince Henry the Navigator, of Portugal, seeking to outflank the hostile Moors of North Africa, sent ships to explore the Atlantic coast of Africa. Mastery of the skills required to sail ships across seas over great distances out of sight of land was achieved gradually. Attitudes had to be changed, old fears overcome, and ships developed to meet the challenge. The maritime technology of the Mediterranean was melded with that of the Baltic-North Atlantic to create a new kind of ship and a new kind of sailing.

De Aloysii Cadamusti Itineribus ad terras incognitas

1515

-

p. 1

p. 1By 1450 Portuguese explorers had reached the Senegal River. When Prince Henry encountered financial difficulties in 1451 and 1452 he allowed Italian merchants to participate in the African trading monopoly. It was with ships of Italian traders that the young Venetian Ca da Mosto made two voyages to the Senegal/Gambia region in 1455 and 1456. Ca da Mosto’s account of those voyages was the first description of sub-Saharan Africa by a European. The young Italian was curious about how other people lived and had an eye for detail. He wrote of the flora, of the customs of the people, and in a lively style conveyed a sense of the way of life there. Iberian noblemen, more concerned with honor and glory, did not perceive the quality of other cultures and wrote largely of their own exploits when placed in similar circumstances. This is the only recorded separately printed edition of Ca da Mosto’s account. It had appeared as part of Fracanzano de Montalboddo’s Paesi novamente retrovati, Vicenza, 1507 (see number 29), and in six subsequent editions of Montalboddo prior to 1515.

Le Navigazioni Atlantiche di Alvise Da Ca Da Mosto, Rinaldo Caddeo, ed., Milan, 1929; John H. Parry, The Discovery of the Sea, New York, 1974, pp. 113-115.

Acquired 1968. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

The Renaissance in Italy was characterized by a desire to recover the knowledge of the classical world which had been lost in subsequent centuries. The Italian humanists hoped at first that the classical geographers knew about remote areas of the world of which they were ignorant. As lost works became available they were invaluable in providing analytic procedures which advanced the quality of geographical inquiry. But the information of the ancients on remote parts of the world was inconsistent and undependable, and, as travelers’ reports about India and Africa arrived in Italy during the fifteenth century, geographers questioned the classical writers. As the century progressed, geographers became more confident in relying upon recent information.

Cosmographia Pii Papae in Asiae & Europae eleganti descriptione

1509

-

p. 1

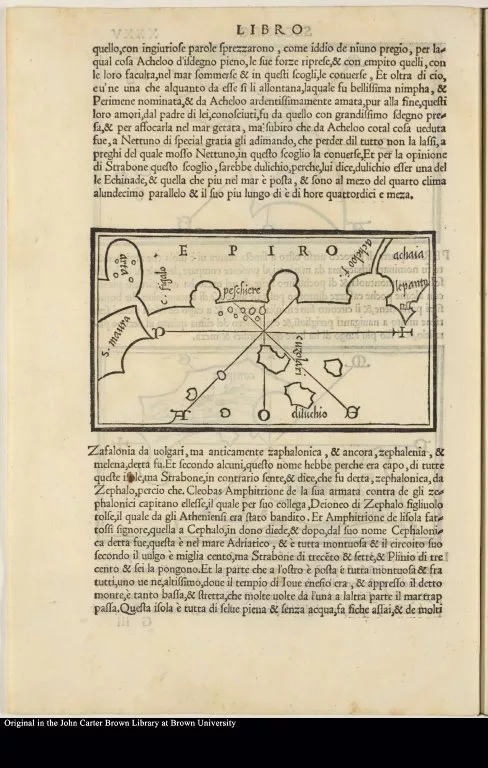

p. 1The fomenting of geographical thought begun with the translation of Ptolemy into Latin was further stimulated by the Council of Florence, convened in 1439 to resolve differences between the Eastern Church and Rome. The Patriarch of Constantinople and the Pope sent their most learned representatives to consider the theological and historical issues separating them. We know that among the discussions of the Church scholars there were extensive exchanges on geographical subjects. The Byzantines preferred Strabo, the Greek geographer, whose descriptive style has led his book to be called a “glorified gazetteer.” The divergent viewpoints of East and West, Strabo and Ptolemy, enlivened and richened the discussions about geography. The discoveries also attracted new information. In 1441 a priest brought Niccolo Conti, a Venetian merchant, to the Council. Conti had recently returned from India and Indo-China where he had lived for twenty-five years. His story was listened to with keen interest and was recorded by Poggio Bracciolini, the Papal Secretary.

The Sienese Piccolomini (he was elected Pope in 1458) wrote the one book which attempted to synthesize Italian geographical thought on remote regions in the period after the Council of Florence. Piccolo- mini’s book on Asia, which circulated in manuscript after 1461, was based on Ptolemy, but many things had to be modernized: the world was clearly bigger than Ptolemy had calculated it to be, and the reports of travelers such as Marco Polo and Niccolo Conti had to be considered. Among other new ideas, Piccolomini concluded that Ptolemy’s idea of a closed Indian Ocean was wrong. His book on Asia was first printed in a larger work, Historia rerum ubique gestarum, Venice, 1477.

This is the first separately-printed edition of his geographical writings, edited by Geoffrey, Tory who recognized that Piccolomini had perceived important geographical concepts a half-century before they could be verified by voyages.

A. A. Renouard, Annales de L'imprimerie des Estienne…, Paris, 1843, p. 6, no. 3; Penrose, Travel and Discovery, p. 10.

Acquired 1969. Benefactors of the John Carter Brown Library.

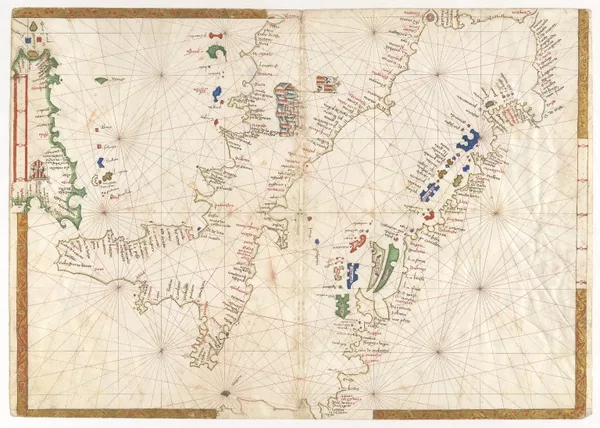

[The Wilczek-Brown Codex]

1440-1460

-

p. 1

p. 1This collection of Ptolemaic maps contains one map of southern Africa that is decidedly un-Ptolemaic. First, southern Africa is not an area portrayed in any other recorded Ptolemaic map collection. Second, it does not present the Ptolemaic notion of a closed Indian Ocean, as do all the world maps in every other recorded manuscript and the editions of Ptolemy printed before 1490. Instead, it is one of the handful of maps, made before Vasco da Gama sailed around the Cape of Good Hope to India, which show Africa surrounded by ocean. In fact, it could be the earliest such map. It may have been made about the time of the Council of Florence and may reflect ideas generated there. It certainly reflects the ambiance of Quattrocento Italy when the ideas of the classical world were recovered, examined, and questioned, and when accepted concepts were revised or rejected.

jcbar 52:43-52; jcb Collection's Progress 101, plate xxxrv; Joseph Fischer, Codex Urbinas Graecus 82, Tomus Prodomus, 526-527, no. 140*; Leo Bagrow, “The Wilczek-Brown Codex,” Imago Mundi, xii, 1955, pp. 171-174; Wilcomb E. Washburn, “Representation of unknown lands in xxv-, xv-, and xvi-century cartography,” Agrupamento de Estudos de Cartografia Antiga, Coimbra, 1969, p. 7.

Acquired 1952. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

2. Columbus

Epistola Christofori Colom: cui [a]etas nostra multu[m] debet: de insuli...

1493

-

p. 9

p. 9As he returned to Spain in February of 1493, Columbus composed an account which was to serve as the public announcement of his discovery. It was not addressed to any particular individual but was enclosed with a letter, now lost, to the Spanish sovereigns. They had manuscript transcriptions made of Columbus’s account and distributed these to court officials. One of these transcripts, endorsed to Luis de Santangel, was printed in Spanish at Barcelona in April 1493. From a better and more accurate manuscript, Leandro de Cosco made a Latin translation, giving it the title Epistola or “letter,” by which it has been known ever since. The translation was sent to Rome and in May the first Latin edition was published. It is this Italian publication which informed Europe of Columbus’s discoveries.

jcb (3)1:19; JCB Collection's Progress 19; Eames (Columbus) 3; Goff C757; Samuel E. Morison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Boston, 1942 (see volume 1, pp. 413-414; vol. 2, pp. 32-45). Acquired 1846 by John Carter Brown.

De insulis inuentis

1493

-

p. 12

p. 12Columbus’s letter appeared in nine Latin editions. After the first, there were two more editions printed at Rome in 1493. Printers in other countries copied the Rome editions; three were printed at Paris and one at Antwerp. The present Basel edition is the first to be illustrated. The local artist who executed the woodcuts portrayed Columbus’s ships as oared galleys. There was one other edition printed in Basel in 1494 as part of another book.

The John Carter Brown Library possesses six of the nine Latin editions of the Columbus letter. By doing so we can demonstrate the way in which the news of Columbus's discovery was presented and also the extent to which the news spread across Europe.

jcb (3)1:18; jcb Collection s Progress 41; Eames (Columbus) 7; Goff C760.

Acquired 1896 by John Nicholas Brown, the donor.

Eyn schön hübsch Lesen von etlichen Insslen die do in kurtzen Zyten fund...

1497

-

p. 9

p. 9The Latin Columbus letter was translated into German and printed in one edition of 1497. It was also translated into Tuscan verse by the Florentine poet Giuliano Dati. Five editions of the poem have been identified, the first printed at Rome in June 1493, the other four at Florence in October of the same year. They are very rare: four are known in single copies (one of which is incomplete) and the fifth is known in two copies.

jcb (3)1:29; Eames (Columbus) 12; Sabin 14638; Goff C762.

Acquired 1851 by John Carter Brown.

Libretto de tutta la nauigatione de re de Spagna de le isole et terreni ...

1504

-

p. 1

p. 1Columbus’s second voyage (October 1493 - June 1496) and third voyage (May 1498 - October 1500) to America were largely concerned with the colonization of Hispaniola. The period began with high hopes and ended with Columbus being sent home in chains.

This little book was the first published account of those voyages. Pietro Martire d’Anghiera (on whom see number 30) included an original narrative of the third voyage and the earliest physical description of Columbus himself. This is one of the most important books on the discovery period, as well as one of the rarest: only two other copies are known.

jcb (3)1:39; jcb Collection's Progress 67; L. C. Wroth, “Introduction” to Libretto de Tutta la Navigatione de Re de Spagna… A Facsimile…, Paris, 1929.

Acquired 1904. Endowment funds.

3. Vespucci

Alberic[us] Vespucci[us] Laure[n]tio Petri Francisci de Medicis salutem ...

1503

-

p. 1

p. 1After returning from his Portuguese voyage, 1501-1502, Amerigo Vespucci sent a letter from Lisbon to his former employer, Lorenzo di Pier Francesco de’ Medici of Florence. The Portuguese ships had sailed down the coast of Brazil for hundreds of miles before turning east and returning home. The mass of land as well as the prodigious flow of the Amazon clearly indicated that they were passing no mere islands off the coast of Asia. In his letter Vespucci was emphatic about that.

What Lorenzo de’ Medici did with the original manuscript we do not know, as the original is lost. He did send a copy to Paris. There, Fra Giovanni Giocondo of Verona, residing in Paris as royal architect to King Louis XII, made a Latin translation of it. It was Giocondo’s translation that was first printed.

jcb (3)1:40; Sabin 99327; Harrisse (bav) 26.

Acquired 1854 by John Carter Brown.

Mundus nouus

1504

-

p. 1

p. 1The second edition of Vespucci’s letter was printed in Venice. The printer, Sessa, used Fra Giovanni Giocondo’s Latin version of the text, as printed the preceding year in Paris. Sessa emended the text and gave it the title Mundus Novus, “New World.” With this title the work spread quickly throughout Europe.

The discovery of a new world was of greater news value than the discovery of a new route to the known East, and contributed to the fact that Vespucci’s letter had wider circulation in the years 1503-1508 than Columbus’s letter had enjoyed a decade earlier.

jcb (3)1:39; Sabin 99328.

Acquired 1850 by John Carter Brown.

Mundus nouus

1504

-

p. 10

p. 10The third edition of the Vespucci letter was printed in Augsburg. Augsburg was the first major commercial city on the German side of the Alps on the trade route through the Brenner Pass from Venice. Venetian goods had been carried in barrels by mule packs across that route for centuries before printing was introduced. When Venice grew to become the leading center of printing in Europe in the 1470’s, barrels filled with sheets of book pages were added to the loads heading north.

In this case Johann Otmar, a printer in Augsburg, reprinted the edition that had appeared in Venice. In the centuries that followed much of the news of America passed to Germany by this route.

jcb (3)1:39; Sabin 99330; Harrisse (bav) 31.

Acquired 1846 by John Carter Brown.

Mundus nouus

1504

-

p. 1

p. 1The Roman printer who published one of the three Roman editions of the Columbus letter, Eucharius Silber, made further textual alterations in the Vespucci text as modified at Venice, and added a title page. This form of the text was the basis of later Latin editions printed at Nuremberg, Strassburg, Rostock, Cologne, and Antwerp. Even later Paris editions follow this “Roman” text rather than the text of the original Parisian edition.

jcb (3)1:40; Sabin 99331.

Acquired 1854 by John Carter Brown.

Von der neü gefunden Region so wol ein Welt genempt mag werden, durch d...

1505

-

p. 3

p. 3European demand for news of Vespucci’s discoveries is reflected here. This is one of two German translations published in twelve different editions at Basel, Munich, Nuremberg, Strassburg, Leipzig, and Magdeburg. These twelve editions contrast with the single German printing of the Columbus letter and reveal how much more extensive was Vespucci’s reputation at the time.

jcb (3)1:41; Sabin 99340; Harrisse (bav) 37.

Acquired before 1865 by John Carter Brown.

Van der nieuwer werelt oft landtscap nieuwelicx gheou[n]de[n] va[n]de[n]...

1507

-

p. 1

p. 1The Vespucci letter was also translated into Dutch and printed at Antwerp. The John Carter Brown copy is the only one recorded. The Dutch edition is noteworthy for Hans Burgkmair's illustrations of natives. Burgkmair’s blocks were carried to Venice and were used a century later to illustrate an edition of Giovanni Botero, Le Relationi universali, printed there in 1618 and again in 1622.

jcb (3)1:48; jcb Collection s Progress 22, plate iv; Sabin 99352; Walter Fraser Oakeshott, Some Woodcuts by Hans Burgkmair, Oxford, Printed for presentation to the members of the Roxburghe Club, i960. Acquired 1871 by John Carter Brown.

In 1505 a letter by Vespucci was published at Florence. This one was addressed to Piero Soderini, Gonfaloniere of the Florentine Republic, who had been Vespucci's schoolmate. In it Vespucci describes four voyages he made to America—including the fictitious one of 1497. Circulation of this letter was peculiar. No other Italian edition is recorded, but parts of it appeared in German as broadsides—and it was translated into Czech. The most influential publication of the Soderini letter was in Latin in the book described in the following entry.

Cosmographiae introductio

1507

-

p. 7

p. 7The word “America” first appeared in this work by Waldseemuller, a German geographer then teaching at Saint-Die in the mountainous Vosges region of eastern France. Waldseemüller admired Vespucci’s accomplishments and published a Latin translation of his letter to Piero Soderini. Waldseemuller did not realize that the new land Vespucci described was the same as the Asian Islands found by Columbus. The geographer proposed to name the “mundus novus” for its presumed discoverer. We should call it America, from the Latin form of Vespucci’s first name, Americus, he wrote, for as Europe and Asia were named for women, America could be named for a man. The name spread quickly and was soon in wide use, and when Waldseemüller became aware of his error and tried to correct his mistake, it was already too late.

jcb (3)1:45; Harrisse (bav) 45; Harold Jantz, “Images of America in the German Renaissance,” First Images of America: The Impact of the New World on the Old, Los Angeles, 1976, vol. 1, pp. 91-106 (esp. pp. 96-100).

Acquired 1846 by John Carter Brown.

4. The Impact of the Discoveries upon Italy

In hoc uolumine continentur hi libri

1496

-

p. 1

p. 1In the seventh century A.D., Isidore, Bishop of Seville, drew a world map which shaped European geographical concepts for nine hundred years. It is simply a “T” inside an “O” (reproduced below). The upper half of the circle represented Asia, the lower two quarters Europe and Africa. The crossing of the “T,” the center of the earth, was Jerusalem, the spiritual and historical center of Christian culture. The expansion of geographical knowledge broke down this world concept.

How difficult the new concepts were to accept is shown in this Florentine book, published slightly more than three years after Columbus had returned. The Isidorian world map is still present in abstract form, and Bishop Lilio is skeptical about news of discoveries: “... unless anyone believes very extraordinary news that the King of Spain, so they say, is sending ships these days to explore new shores.”

jcb (3)1:25; Harrisse (bav) 17; Sabin 41067; World Encompassed 17. Acquired 1903. Endowment funds.

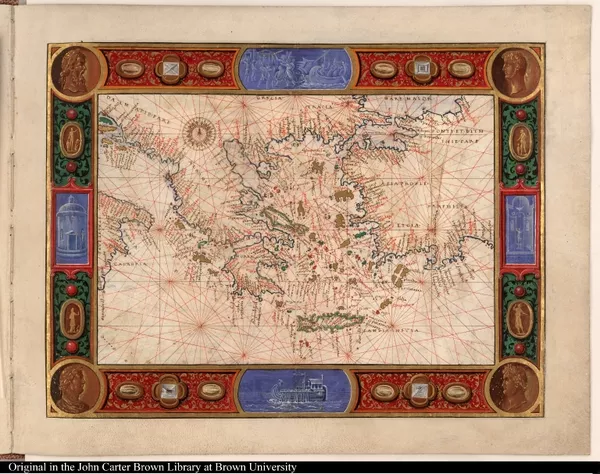

In hoc operae [sic] haec contine[n]tur Geographia Cl. Ptholemaei a pluri...

1507

-

p. 1

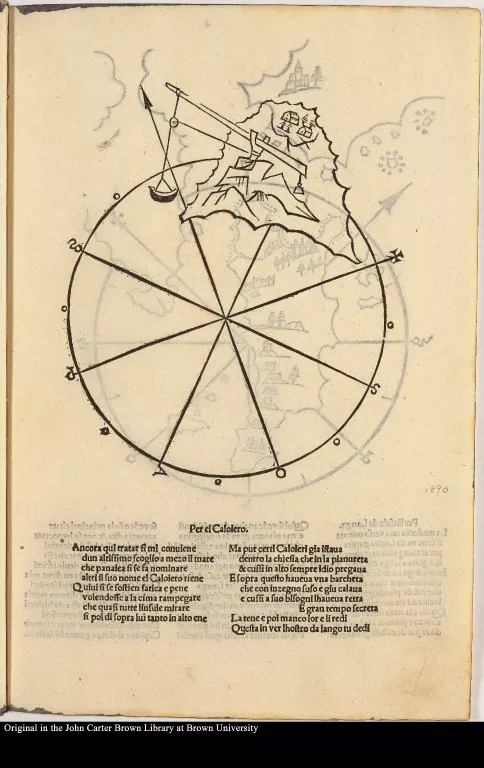

p. 1In the sixteenth century, editors of Ptolemy attempted to reconcile Ptolemy’s work with the discoveries of lands unknown to the classical geographer. The 1507 and 1508 editions of Ptolemy produced in Rome are noteworthy for the addition of a copperplate engraved map made by a German, Johannes Ruysch. The map is a planisphere on a conical projection with its apex at the North Pole. It contains an accurate Africa, an India whose mass is fully realized, and evidence of knowledge of the discoveries of both Columbus and Vespucci.

This map, probably derived from a now-lost Italian manuscript, suggests what an heroic effort was involved when cartographers in the first years of the discoveries tried to make sense of the fragmented information that filtered back to Europe. The efforts of sixteenth-century Italian mapmakers to bring order to their maps is treated as a separate section at the end of this catalogue, but here we wish to show one of the important early maps and the difficulties its maker faced. On this map, Newfoundland appears as an Asian peninsula, South America as a disconnected island, and Hispaniola as an island near Japan. Ruysch, and his model, obviously had difficulties in understanding how reports of discoveries related one to the other.

jcb (3)1:44; JCBAR 59:33-37; Sabin 66475; Bradford F. Swan, “The Ruysch map of the world (1507- 1508),” from Papers of the Bibliographical Society ofAmerica, vol. 45, n. 3,pp. 219-236; World Encompassed 53. Acquired 1959. The gift of George H. Beans.

One of the forces which most threatened and stimulated the European order was the power of Islam to the east and south. Italian traders were the Europeans most regularly in contact with the Islamic world, and Italy was the country most exposed to the naval power of Islamic rulers. The fact that the discovery and development of America were about to alter Europe in as extensive and radical a way as had the Crusades against Islam a few centuries before was not self-evident in 1500.

Petri Paschalici Veneti oratoris Ad Hemanuelem Lusitaniae regem oratio

1501

-

p. 1

p. 1For Italians the discovery of new lands and new routes to the Far East did not reduce the immediate threat that Turkish power presented in the Near East. In this oration the Venetian ambassador to Lisbon praises King Manuel profusely for the Portuguese discovery of new lands and peoples unknown to the ancients. But he admonishes Manuel not to allow the discoveries to distract Portugal from attending to the main threat of Europe: the power of the Turks in the eastern Mediterranean.

An English translation has been published by Donald Weinstein: Ambassador from Venice: Pietro Pasqualigo in Lisbon, 1501. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press [i960].

Acquired 1975. Endowment funds.

Ioannis Francisci Pici Mirandulae domini et concordiae comitis, De rerum...

1507

-

p. 5

p. 5Count Pico was a philosopher as well as a ruler of the tiny dukedom of Mirandola near Modena. He believed that Columbus’s “discovery” that the islands of “Asia” could be reached by sailing west might provide a potential base from which the Turks could be attacked from behind.

Adolf Schill, Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola und die entdeckung Amerikas, Berlin, 1929.

Acquired 1976. Endowment funds.

In hoc volumine hec continentur. De imperio militantis ecclesiæ libri qu...

1517

-

p. 1

p. 1The discovery of people unaccounted for in the Bible or the writings of ancient authors was as much of a challenge to the limited world of Europe as were new lands and new oceans.

As the extent of the western islands and their heathen populations became apparent to Europeans, a few in the Church realized that a great opportunity to extend its influence was presented to them, that indeed they had an obligation to send missions.

This book contains one of the first discussions of the implications of conversion after military conquest. The author, a Dominican theologian and native of Milan, was one of the men in the forefront of a realization of the consequences of the conquests in the New World.

Sabin 35264; Harrisse (bav) additions 49; Streit 1:13.

Acquired 1976. Endowment funds.

De habilitate et capacitate gentium siue Indorum noui mundi nu[n]cupati ...

1537

-

p. 1

p. 1When Cortés conquered Mexico, Catholic Spain gained political control over more than 25 million natives. The “spiritual conquest” of these people which began in 1523 was of no less significance and was much more complicated. As the Spanish crown regarded the conversion of the Indians as justification for their rule, success was vital. But the Church had never satisfactorily resolved whether or not pagans could be saved. A strong tendency, derived from Aristotle, considered pagans “natural slaves” with no rights whatsoever. In Rome the leadership of the Church was faced with a moral decision: were the Indians capable of becoming Christians, and, if so, should their rights be protected before conversion was actually achieved?

This book, of which no other copy is recorded, is a letter from the Dominican Bishop of Tlaxcala in Mexico arguing strongly that the Indians were rational and spiritual beings capable of becoming Christians. Garcés urges the Pope to offer the protection of the Church to the lives and property of the native population.

The letter was published as part of a campaign to convince Pope Paul III that he should act. Pope Paul responded by issuing his bull Sublimus Deus on 2 June 1537. This bull is a great and important document. It accepted Garcés’s arguments and declared Indians “truly men.” In forceful language Paul stated the Church’s mission and offered the protection of Christ to all people.

Facsimile published by Lewis Hanke, “The theological significance of the discovery of America,” First Images of America, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1976, vol. 1, pp. 375-389; Harrisse (bav) additions 12. Acquired 1969. Benefactors of the John Carter Brown Library.

La pazzia

1541

-

p. 1

p. 1An imitation of Erasmus’s Praise of Folly, this encomium to madness includes a passage lauding the natives of the West Indies for their disregard of material things. They are compared with the citizens of Plato’s Republic who care nothing for gold and silver and share property in common.

1541 edition acquired 1975. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

La pazzia

-

p. 1

p. 1Albergati draws upon the descriptions of American natives by Columbus and Vespucci. But his idealization of them as Noble Savages is new and comes earlier than scholars have previously believed this to have occurred.

1543 edition acquired 1976. Louisa Dexter Sharpe Metcalf Fund.

Descrizione della entrata della serenissima regina Giouanna d'Austria

1566

-

p. 1

p. 1America represented an exotic land from which came strange animals, new plants, people in wild costumes. As Giovanna d’Austria, engaged to marry the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Francesco de’ Medici, entered Florence in 1566, her procession passed through streets lined with symbolic decoration—a stationary “parade” through which she and her party moved as spectators. She entered the western gates (Porto Prato) and soon encountered men costumed as the great figures of the Florentine past, among whom were Amerigo Vespucci and Paolo del Pozzo Toscanelli. Later, as she passed the Spini palace, there was a huge painting depicting Peru, an allegorical representation containing nymphs, putti, birds, and exotic American animals. As the painting has apparently not survived, the only record of its appearance is in this verbal description of it.

Sabin 47453.

Acquired 1976. Endowment funds.

5. Italian Historians of the Great Explorations

Le voyage et nauigation, faict par les Espaignolz es Isles de Mollucques...

1525

-

p. 7

p. 7The only contemporary printed account of Magellan’s voyage around the world by a participant was written by a nobleman of Vicenza, Antonio Pigafetta. Pigafetta, “prompted by a craving for experience and glory,” as he said of himself, joined the fleet that sailed from Seville in August of 1519. He was aboard Magellan’s flagship Trinidad, and was one of the few survivors of that difficult first circumnavigation.

Upon his return, Pigafetta informs us, he presented Charles V, who had sponsored the expedition, a copy of his diary (now lost). He then went to Lisbon, where he presented King João with a manuscript, and then on to Paris where he offered another manuscript to Marie Louise, regent and mother of Francis I. Neither of these versions is known.

Pigafetta wrote his book in Italy in 1524.

In 1525 he visited the court of the French King, and his lively, gossipy account of the voyage was published in French translation that year. This helped to stimulate royal support of Verrazzano’s project which was intended to achieve a similar result—to find a trade route to the East Indies by a northwesterly route, Spain and Portugal having laid claim to routes by the southwest and southeast.

jcb (3)1:95; jcb Collections Progress 20; Harrisse (bav) 134; James A. Robertson’s edition and translation, Cleveland, 1906, is still considered the best text. Acquired before 1856 by John Carter Brown.

Verdadera relacion: de lo sussedido en los reynos e prouincias d[e]l Per...

1549

-

p. 5

p. 5Nicolao de Albenino was a Florentine, born about 1514, who is presumed to have gone to Peru in 1535. During the next forty years he was one of a large number of Italians who were employed in the great silver mines of Potosi, and he eventually rose to a position of considerable responsibility.

This book is the earliest account of the Gonzalo Pizarro rebellion of 1544-1548. Albenino played a role in the turbulence as a loyalist to the Spanish crown. His was the only account by a participant and eyewitness to the rebellion to be published at the time, and it is still an important source for that important incident which tested Spain’s ability to rule its distant colonies. Only one other copy of this book is known—in Paris at the Bibliotheque Nationale.

jcbar 39:2-8. Obtained in 1939. The gift of Mrs. Jesse H. Metcalf.

La historia del Mondo Nuouo

1565

-

p. 1

p. 1Benzoni, born of a poor Milanese family, went to America as a young soldier in 1541. He served in the Spanish army for fourteen years in such varied posts as Haiti, Cuba, Panama, Colombia, and Peru. His narrative reflects the hard conditions of his service: it is rough and ill-written but vivid in its details, conveying with great fidelity the dangers and deprivations of an ordinary soldier. There was no room for flattery in such a book, and Spaniards were upset by the harsh portrayal of their colonies which Benzoni presented. Benzoni’s book was reprinted many times, often as anti-Spanish propaganda, and it played an important role in creating “the black legend,” the negative impression of Spanish rule held by many.

jcb (3)1:226-227; Sabin 4790. Acquired ca. 1847 by John Carter Brown.

Paesi nouamente retrouati. et Nouo Mondo da Alberico Vesputio Florentino...

1507

-

p. 1

p. 1This is the first printed collection of voyages and travels of the Age of Discovery. It includes the first printed appearance of Ca da Mosto’s travels to Africa as well as reprints of accounts of Columbus’s first three voyages and Vespucci’s “third voyage. It was translated into Latin, German, and French within a few years and was read throughout Europe. It is believed that more people learned the news of the discoveries in both America and Asia from this book than from any other.

jcb (3)1:43; Harrisse (bav) 48; Church 25; Penrose, Travel and Discovery, p. 277.

Acquired 1849 by John Carter Brown.

P. Martyris Angli Mediolanensis Opera

1511

-

p. 9

p. 9Peter Martyr (to give his Anglicized name), the first historian of America, was born at Arona on the shores of Lago Maggiore. In 1494 he was ordained and in the same year was appointed tutor to the children of Ferdinand and Isabella. He was a friend of Columbus, Vasco da Gama, Cortés, Magellan, Cabot, and Vespucci, and, from conversations with these men as well as from his position as a member of the Council for the Indies, he was able to get accurate reports. He had started to prepare a history of the discovery of the Indies as early as 1494.

Samuel Eliot Morison wrote of Peter Martyr, “The value of Peter Martyr’s letters and of his Decades is very great for he had a keen and critical intelligence which pierced some of the cosmographical fancies of Columbus… and he gives us more information about the second Voyage than any other contemporary historian.”

jcb (3)1:52; Harrisse (bav) 66, additions 41; World Encompassed 52, plate xvii. Acquired 1846 by John Carter Brown.

Summario de la generale historia de l'Indie Occidentali

1534

-

p. 1

p. 1Ramusio, a Venetian, edited the second collection of texts (after Montalboddo’s in 1507) on America. He published three texts: two lengthy histories of recent explorations by Peter Martyr and Fernandez de Oviedo, and a third short piece, a translation of a first-hand anonymous account of newly discovered Peru, La conquista del Peru, which had appeared at Seville in 1534.

Not as extensive as Montalboddo’s Paesi novamente retrovati or his own great Navigationi e viaggi, the work served to provide Italians with accurate information at a time when explorers were learning the dimensions of the two continents.

jcb (3)1:114; Harrisse (bav) 190; Church 69. Acquired 1846 by John Carter Brown.

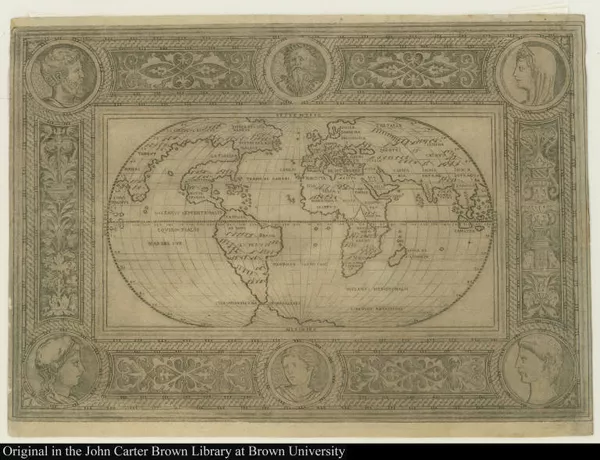

Terzo volume delle nauigationi et viaggi nel quale si contengono le naui...

1556

-

p. 5

p. 5Nearly twenty years after publishing his Summario historia de VIndie, Ramusio began a massive publishing project: he assembled texts of discovery and exploration in three thick folio volumes, each one devoted to a continent. The third volume, the one on America, contains, among many basic documents, the first printed report of the voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano.

The map “La Nuova Francia,” executed in woodcut by Giacomo Gastaldi, accompanied the Verrazzano text. It represents the coast from New York Bay to Labrador—Verrazzano’s “Port du Refuge” is Narragansett Bay.

jcb (3)1:194; George B. Parks “The contents and sources of Ramusio’s Navigationi,” Bulletin of the New York Public Library, 59, 6, June 1955, pp. 279-313; Wroth, Verrazzano, pp. 205-209. Acquired before 1854 by John Carter Brown.

Apparato all'historia di tutte le nationi. Et il modo di studiare la geografia

1598

-

p. 1

p. 1Italian Jesuits organized materials for instruction in their schools in clear, tightly structured ways that looked forward to modern pedagogy. In this handbook for advanced students of history in Jesuit schools, the learned Jesuit Antonio Possevino included a chapter entitled “Historici delle cose dell’India.” This appears to be the first extensive list of books relating to America. Most of the works are easily identifiable, and many can be found in the John Carter Brown Library. Some of the books cited, such as Ferdinand Colombo’s life of his father and Lorenzo Gambara’s poem about Columbus, are included in this catalogue.

Backer 6:1079-80. Acquired 1968. Louisa Dexter Sharpe Metcalf Fund.

Italy as Channel of Information [after 5]

Passio gloriosi martyris beati patris fratris Andree de Spoleto ordinis ...

1532

-

p. 1

p. 1The conquest of the Mayan people of the Yucatán peninsula began in 1527 and resistance was so determined that large sections were brought under Spanish control only in 1697. This pamphlet includes two letters, dated Mexico, 6 June 1531 by Martín de Valencia and Juan de Zumárraga, Franciscan missionaries in Yucatán, as well as a letter on the martyrdom of another Franciscan, Andrea da Spoleto, in Africa. The pamphlet is reprinted from an edition of the letters printed at Toulouse in April 1532, where a French translation was also published. The edition printed at Bologna was unrecorded before the Library obtained this copy of it.

Acquired 1976. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

Libro primo de la conquista del Peru & prouincia del Cuzco de le Indie O...

1535

-

p. 7

p. 7Francisco de Xerez, Francisco Pizarro’s secretary, departed from Spain with his employer in 1530. He participated in the decisive early stages of the conquistador’s campaign. After he had murdered the Inca ruler Atahualpa, Pizarro, who was illiterate but no fool, ordered his secretary to write an account of the conquest, accentuating the heroism and boldness, and to get back to Spain with the story fast.

By accompanying the first gold shipment home Xerez could blunt reaction against the cruel, deceitful manner of conquest by his words and by lucre. The Verdadera relation was published in Seville in July 1534. It was translated for a Venetian audience and published in March the next year. This is a longer and more detailed account than the first account of Peru published by Ramusio a few months earlier.

jcb (3)1:119; Harrisse (bav) 201; Church 73; Sabin 105721. Acquired 1846 by John Carter Brown.

Auisi particolari delle Indie di Portugallo riceuuti in questi doi anni ...

1552

-

p. 1

p. 1The Society of Jesus was authorized in 1540, and in 1542 its first missionary, St. Francis Xavier, went out to India. The first mission to America was Father Nóbrega and five companions who went to Brazil in 1549. St. Ignatius Loyola organized the order as a military “company.” In order to maintain high standards and rigid discipline, organization was essential, particularly as the Society’s missions were so widely dispersed. To exercise control Loyola had each missionary report to regional supervisors and send information on the lands in which they were stationed. He wrote: “... if there are other things that may seem extraordinary, let them be noted, for instance, details about animals and plants that either are not known at all, or not of such a size, etc. And this news—sauce for the taste of a certain curiosity that is not evil and is wont to be found among men—may come in the same letters or in other letters separately.”

The reports were edited in Rome and Loyola quickly realized that they would have wide appeal. In 1552 the Society began to publish them regularly. In this first Jesuit letter there is a report from the new and struggling mission to Brazil.

jcb (3)1:166; Streit 2:1221, 4:669; Europe Informed, pp. 107-108. Acquired 1846 by John Carter Brown.

VI. The Reputation of Columbus in Italy

R. Volaterrani Commentariorum urbanorum liber primus. [-XXXVIII.]

1506

-

p. 1

p. 1This book is a general encyclopedia which contains a chapter, “Loca nuper reperta,” on Columbus’s discoveries. It is the first book of a general nature which included information about Columbus; it appeared the year of his death, 1506.

Harrisse (bav) additions 22; Sabin 43763. Acquired 1971. Benefactors of the John Carter Brown Library.

Psalterium, Hebr[a]eum, Gr[a]ecu[m], Arabicu[m], & Chald[a]eu[m]

1516

-

p. 5

p. 5This psalter in five languages is the first polyglot liturgical work ever printed. The editor, Agostino Giustiniani, Bishop of Nebbio, included a paragraph on Columbus as a note to Psalm xix, 4. This note is the first published claim by the city of Genoa to the man who was to become its most famous son.

The Library has two copies of the beautifully printed psalter; this one is on vellum.

jcb( 3 )i: 64 ; Harrisse (bav) 88; Sabin 66468. Acquired before 1865 by John Carter Brown.

Historie del S.D. Fernando Colombo

1571

-

p. 7

p. 7Fernando Colón was Columbus’s illegitimate son. He was brought up as a royal page and became wealthy enough to form a library of 15,000 volumes.

He saw his father brought home in chains, went with him on the fourth voyage, and dedicated his own life to writing a biography to vindicate him. His completed manuscript (now lost) found its way to Italy, and this book was the first appearance of this important source for the Discoverer’s life.

jcb (1)3:244; Church 114; Sabin 14674. Acquired 1846 by John Carter Brown.

Pauli Iouii Nouocomensis Episcopi Nucerini Elogia virorum bellica virtut...

1551

-

p. 1

p. 1One of the significant measures of the rise of Columbus’s reputation was his inclusion in this collection of military men. Paolo Giovio, Bishop of Nocera, gathered portraits of heroes of the past, including Romulus and Alexander the Great, as well as of the leaders of his time, among whom was Cortés. He installed them in his private museum on Lake Como. Among the portraits of recent heroes was one of Columbus.

In this book the Bishop described the paintings in his collection. The Library also possesses the Italian translations of this book.

Acquired 1925. Endowment funds.

Pauli Iouii Nouocomensis Episcopi Nucerini Elogia virorum bellica virtut...

1571

-

p. 1

p. 1This Basel 1571 edition of Giovio’s book on military leaders is the first that contains woodcut copies of the oil paintings in Giovio’s collection. The likeness of the woodcut of Columbus is not authentic, but it is the first published portrait of Columbus and influenced later pictures of him. The significance of its appearance is that the likeness was considered of sufficient importance to collect and to publish in the third quarter of the sixteenth century.

This copy of the book belonged to John Evelyn, the English “virtuoso” (1620- 1706), whose library was recently dispersed at auction.

Acquired 1978. Louisa Dexter Sharpe Metcalf Fund.

Columbus as a Theme in Cinquecento Italian Poetry [after 6]

Laurentii Gambarae Brixiani De nauigatione Christophori Columbi libri quattuor

1581

-

p. 1

p. 1In 1536 a courtier to Charles V suggested to young Gambara that he treat the discovery of America in poetry. Not one to be rushed, Gambara set out forty-five years later to write an historical poem. He used Peter Martyr and other original sources for his information, adhered closely to historical fact, and eschewed the traditional devices of epic poetry: there are no long speeches, no catalogues of ships, no supernatural machinery. The poem was well received, as indicated by the fact that it was reprinted in 1583 and 1585.

jcb (3)1:286; Sabin 26500; Leicester Bradner, “Columbus in Sixteenth-Century Poetry,” in Essays Honoring Lawrence C. Wroth, Portland, Maine, 1951, pp. 16-19. Acquired 1836 by John Carter Brown.

Iulii Caesaris Stellae nobilis Romani Columbeidos libri priores duo

1590

-

p. 7

p. 7The poets following Gambara who used Columbus as a theme altered fact to make their stories attractive. This Latin poem is modeled upon Tasso’s La Gerusalemme liberata and its main theme is Satan’s opposition to the conversion of the heathen. In order to stop Columbus, Satan disguises himself as an Officer of the Fleet and proceeds to incite a mutiny. God sees this and sends an angel to warn Columbus in a dream, and the voyage continues in this fantastic manner. Stella completed only two books of his projected epic, but they stimulated other poets to use the voyage of Columbus as an epic theme.

jcb (3)1:324; Sabin 91217; Leicester Bradner, op. cit., pp. 19-23. Acquired 1846 by John Carter Brown.

Il mondo nuouo

1596

-

p. 1

p. 1This epic poem of twenty-four cantos is written in ottava rima stanzas in the style of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso. It is full of supernatural events and romantic incidents and has little regard for historical fact.

In this version King Ferdinand of Spain accompanies Columbus on his second voyage and then conquers Mexico with a slight assist from Cortés. Although overshadowed by the King, Columbus appears with the conventional virtues of a perfect courtier: he is pious, learned, brave, wise, loyal.

jcb (3)1:342; Sabin 27473; Leicester Bradner, op. cit., pp. 23-27. Acquired 1846 by John Carter Brown.

Del mondo nuouo

1617

-

p. 1

p. 1A native of Matera in Basilicata, Stigliani grew up in Naples where he knew the poet Marino and, possibly, Tasso. These were the great poets of his time, the ones admired in courtly circles, and he emulated them, as well as Ariosto, in this bid for poetic glory.

Stigliani used Columbus and the discovery of America as a framework of reality in which to tell fanciful stories of fictional characters in exotic settings. Instead of achieving glory, he was severely criticized for his excesses by contemporary poets, including Marino himself and Angelico Aprosio.

jcb (3)1:122; Sabin 91728. Acquired 1869 by John Carter Brown.

VII. Vespucci as a Theme in Cinquecento Italian Poetry

L'America

1611

-

p. 9

p. 9This is the first canto of an epic poem on Vespucci. Gualterotti, a minor painter as well as a minor poet, presented it as a sample to Cosimo Medici II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and offered to show him the remainder of the poem if the first canto was received with favor. Medici patronage was not forthcoming, and only this first canto—the “prospectus”—was ever printed. What happened to the manuscript of the other cantos, if, indeed, they were ever written, is not known.

This is the earliest known printed poem on Vespucci, and because of the circumstances of its publication, it is very rare.

jcb (3)2:75; Sabin 29050. Acquired in 1846 by John Carter Brown.

L'America poema eroico

1650

-

p. 1

p. 1A Florentine poet, lawyer, member of the Accademia della Crusca, Bartolommei Smeducci intended to write a new Odyssey, in imitation of Homer, but elevated through an understanding of Aristotle. The voyage of Amerigo Vespucci is given allegorical significance, ample classical decoration, and considerable length: there are 560 folio pages of double columns of verse.

jcb (3)1: 343 - 394 ; Sabin 3797; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Rome, 1977, vol. 6, p. 789; Gamba 1782. Acquired 1846 by John Carter Brown.

VIII. Italian Physicians and America

Capitulo ouer recetta delo arbore ouer legno detto Guaiana: remedio cont...

1520

-

p. 1

p. 1Columbus’s companions of his first voyage brought back with them a virulent form of syphilis. The disease swept swiftly throughout Europe: it was the first way in which America influenced the lives of those in the Old World. Cures were desperately sought. The first medicine for syphilis was the bark of the guaiac tree of the West Indies, a cure learned from the Indians. Thus, guaiac bark was the first botanical gift to the Old World. This is an early description of guaiac bark. The book is unrecorded in bibliographies of Americana or of medicine.

Francisco Guerra, “The Problem of Syphilis,” in First Images of America: The Impact of the New World on the Old, Los Angeles, 1976, vol. 2, pp. 845-851. Acquired 1968. Lathrop Colgate Harper Fund.

Hieronymi Fracastorii Syphilis sive Morbus Gallicus

1530

-

p. 1

p. 1The name of the disease originally called “the French Disease” was changed to syphilis after the protagonist of this Latin poem. In the poem a shepherd, Syphilis, is imagined to be the first sufferer from the malady.

Girolamo Fracastoro, a physician, astronomer, and man of letters of Verona, uses the story of the shepherd to describe the symptoms and offer means of treatment for the disease. He was the first to recognize it as being a venereal disease, thus making this a substantial medical as well as literary contribution.

jcb (3)1:100; Harrisse (bav) additions 91.

Acquired 1906. Endowment funds.

Anastasis corticis Peruviae; seu Chinae chinae defensio

1663

-

p. 1

p. 1Chinchona bark which contains quinine was first used by Indians of the jungles of Ecuador, Peru, and Chile to treat malaria. Missionaries learned of it in the 1630’s, and by 1650 Roman Jesuits were encouraging its use. Chinchona was popularly called “Jesuit Bark,” and it was taken as a patent medicine for all fevers.

Sebastiano Bado, a Genoese physician who specialized in sanitation and public health, was a strong believer in the effectiveness of chinchona. He was one of the first reputable medical doctors to support its use, and his book is one of the first to examine the bark scientifically.

Garrison-Morton 1826; Edward John Waring, Bibliotheca therapeutica, London, 1878-1879, 338. Acquired 1968. Louisa Dexter Sharpe Metcalf Fund.

Francisci Torti Mutinensis, Sereniss. Raynaldi I. Mut. Reg. Mirand. &c. ...

1712

-

p. 1

p. 1Before Torti’s work appeared quinine was used to treat all fevers. The frequent failure of quinine cast doubts upon its effectiveness. Torti, who isolated and named malaria, recognized that quinine was appropriate only for the cure of malarial fever. This book represents a milestone in man’s conquest of a disease that has killed millions.

Garrison-Morton 5231. Acquired 1968. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

IX. Italian Missionaries on the Frontiers of Seventeenth-Century America

Passage par terre a la Californie Decouvert par le Rev. Pere Eusebe-Fran...

1705

-

p. 1

p. 1The Jesuit Father Kino founded a score of missions which are now Arizona towns. Bom at Segno, near Trento in Italy, Kino had hoped to join the mission in China but was sent to the Spanish frontier in northern Mexico. He used his considerable mathematical skills to map large areas of what is now the southwestern United States.

Kino supervised the establishment of missions in Baja California and organized an overland supply system for them. He soon realized that the old maps of the area were drastically incorrect, so he prepared a new one. His map of Baja California, first included in a collection of letters from Jesuit missions, finally put to rest the notion that California was an island. The hispanicized form of his name is now used rather than the Italian Chino.

Ernest J. Burrus, Kino and the Cartography of Northwestern New Spain, Tucson, 1965. Acquired 1957. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

Breue relatione d'alcune missioni de' PP. della Compagnia di Giesù nell...

1653

-

p. 1

p. 1Between 1642 and 1651, Bressani, a native of Rome, served as a Jesuit missionary in Canada. The first two years were spent in learning Indian language and customs; then he requested permission to proselytize among the most distant Hurons. He was captured by the Iroquois, was cruelly tortured, sold to a Dutch trader, and returned to Europe. Undaunted, he returned to Quebec in 1645 and for seven years worked among the Hurons, who were constantly attacked by Iroquois. When the Hurons were driven from their lands, the order returned some of the missionaries to Europe. Among them was Bressani, who recorded his experiences during the turbulent early years of French Canada.

jcb (3)2:428; Sabin 77734; Streit 2:2585. Acquired 1846 by John Carter Brown.

Historica relacion del reyno de Chile

1646

-

p. 9

p. 9This work, the first general history of Chile, was written in part to encourage missionaries to come to the Spanish frontier, and was published in Rome simultaneously in Italian and Spanish. Our second copy of the Spanish-language edition, originally in the Huth collection, contains a large engraved map of Chile.

This detailed map, known only in this copy and one in Paris, was the fullest record of the southwest coast of South America at the time, and the source of maps of the area for a century. This is a striking example of the kind of important information that missions sent to Rome and that was first published there.

JCB (3)2:345; Lawrence C. Wroth, Alonso de Ovalle's Large Map of Chile, 1646,” in Imago Mundi, xiv (1959), pp. 90–95. Acquired 1917. Endowment funds.

Viaggio

1671

-

p. 1

p. 1Michel Angelo de Gualtini and Dionigi Carli were Capuchin missionaries sent to the Congo. Because they stayed at Pernambuco in Brazil on their way to Africa (their description of Recife after the expulsion of the Dutch is the second known account) and because they witnessed, and opposed, the slave trade, they are important sources for Brazilian history.

Other Italian Capuchins sent to the Congo—Cavazzi da Montecuccolo, Merolla da Sorrento, and Zucchelli da Gradisca—are also important historians of Brazil and the Congo.

Streit 16:4486; cf. Borba de Moraes 1:131. Acquired 1969. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

X. The Seventeenth Century

Ragionamenti

1701

-

p. 1

p. 1Francesco Carletti was born in Florence, probably in 1573. At the age of eighteen he was sent to Seville to learn the intricacies of international maritime trade. He set out from Spain in 1594 on a trading voyage that by 1602 had lengthened into a circumnavigation of the globe. Dutch privateers in the Atlantic deprived him of the profits of his travels, and he returned home to Florence richer only in experience. Observant and articulate, his reports were welcomed by Ferdinando de Medici to whom Carletti presented a manuscript. His reports were published almost a century later—in 1701.

jcb (1)3:5; Sabin 10908; there is a modern edition, edited by Gianfranco Silvestro, Torino, Einaudi [1958]- Acquired 1865 by John Carter Brown.

La storia del governo di Venezia

1681

-

p. 9

p. 9Some Italians of the seventeenth century blamed the discovery of America for the decline of the Italian states in the order of international powers. Amelot de la Houssaye, writer and translator, born at Orleans, France, served as secretary to the ambassador to Venice and was in a position to examine the Venetian state closely. Venice had slipped badly both in its political effectiveness and its economic strength since 1492.

In this book on the history of the government of Venice first published at Paris in 1676-1677, Amelot refers to the damage to Venetian commerce caused by competing imports from America.

Acquired 1968. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

La science de l'homme de qualité ou L'idee generale de la cosmographie,...

1684

-

p. 1

p. 1In this handbook on the geography and history which every gentleman should know there are a few pages on America. The author, however, obviously regarded information about America of little consequence: in this book New Amsterdam, which twenty years before had passed to the English and been renamed New York, is still listed as a Dutch colony!

Further research and further collecting may alter our view, but it seems that this accurately reflects the limits of seventeenth-century knowledge of America.

Acquired 1971. The gift of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel J. Hough in memory of Lawrence C. Wroth.

Descrizione della Luigiana

1686

-

p. 1

p. 1Hennepin, Recollect brother, explorer, teller of tall tales, accompanied LaSalle on his 1678 exploration of the Mississippi. This book, a translation of his Description de la Louisiane, first published at Paris, 1683, is regarded as an accurate account of LaSalle’s expedition.

Hennepin’s later writing was more fanciful: it seems that in order to match the success of this book he decided to invent further adventures. This is the first book in Italian describing the Midwest of the United States.

jcb (1675-1700) 165; Sabin 31356; Streit 2:2732. Acquired 1847 by John Carter Brown.

Il genio vagante

1691-1693

-

p. 1

p. 1The great Italian collections of voyages by Montalboddo and Ramusio (numbers 29 and 32) are imitated in this small, cramped, anonymously published work. The account of the French explorations in the Mississippi Valley, the vast region labeled “Luigiana,” is an abridged version of the Bologna, 1686, Italian translation of Hennepin.

As modest as this publication is, it did bring together many texts of more recent explorations which would have otherwise not been available to Italian readers.

jcb (1675-1700) 250-251; Streit 1:715. Acquired 1969. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

Giro del mondo

1719

-

p. 1

p. 1Gemelli Careri is a mysterious figure. For many years scholars thought that his voyage was fictional and that his work was written in an armchair, copying other books. But his observations have been verified over the centuries, and his voyage is now accepted as factual. His world travels were first published at Naples in nine volumes in 1699.

Gemelli Careri sought out historical materials about the places he visited and his sixth volume, which deals with Mexico, contains information taken from pre-conquest codices. Among the illustrations are Aztec warriors derived from such a manuscript. There are ample passages on natural history: in this volume vanilla and cacao, both plants native to America, are among those illustrated. He also described the life and economy of the areas he visited, and in this volume there is an illustration of a Mexican silver mine.

jcb ar 21:7. Acquired 1920. Endowment funds.

XI. Italian Erudition and the Preservation of American Artifacts

Seconda nouissima editione delle Imagini de gli dei delli antichi

1626

-

p. 1

p. 1Cartari was born in Reggio Emilia, probably in 1531. His life was spent in service to the Estes, Dukes of Ferrara, who patronized arts and learning. When Cartari first published his Imagini de i Dei in 1556 he was concerned with the images of gods in Classical Antiquity and the Near East. In this posthumous edition the editor, Lorenzo Pignoria, added images from Asia and America in expanding the work.

The images of Aztec gods are taken from a manuscript in the Vatican library. Some of the early missionaries destroyed many idolatrous Mexican manuscripts in order to eradicate the Aztec religion, but, as the Church's position became secure, many others were saved. It was thus that the great library at the Vatican became a depository of many important Aztec codices.

jcb (3)2:198-99; Sabin 11105; there is a good biography of Cartari by M. Palma in the Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Rome, 1977, vol. 20, pp. 793-796. Acquired 1910. The gift of William E. Foster.

Note ouero memorie del museo di Lodouico Moscardo, nobile veronese, acad...

1656

-

p. 1

p. 1Moscardo’s “cabinet” or museum of natural history and archaeological finds was one of the principal collections of rarities of its day.

Among the objects from America listed in this annotated catalogue of the Collection is a pair of Aztec slippers made with great skill. Many American-Indian pieces now in public museums were preserved in the private “cabinets” of this kind.

Acquired 1973. Lathrop Colgate Harper Fund.

Lettera apologetica dell'Esercitato accademico della Crusca

1750-1751

-

p. 5

p. 5Raimondo di Sangro was born at Torremaggiore (Foggia) of one of the most powerful noble families of the kingdom of Naples. He was educated by Jesuits and learned numerous languages. After military service as a young man, he devoted his life to mechanical invention, study, and writing. The striking title page of this book—printed in orange, green, and black—was produced by a process invented by him. The Enciclopedia Italiana says of him: *His bizarre and acute genius, helped by a little charlatanry, yielded him a reputation throughout Italy and beyond.

In this book the Prince defends Lettres d'une Peruvienne, published anonymously by Madame Graffigny, Paris, 1747. Her novel consists of thirty-eight letters supposedly written by the Inca Princess Zilia to her lover Aza. The letters were written in Quipu of the Incas according to Graffigny. Quipu are cords, usually about two feet in length, composed of varicolored threads.

The word quipu itself means knot, and, by a system of color-coding the threads and making patterns with the knots, the Incas recorded statistical information. The Prince believed that Quipu was a writing system and defended Madame Graffigny from detractors of her fiction. In defending the veracity of a fiction, di Sangro was off the mark, yet his book is the earliest full study of the Quipu writing system.

jcb (1)3:932; Sabin 40560. Acquired before 1870 by John Carter Brown.

XII. Italian Influence on the Arts in Colonial America

La Partenope fiesta

-

p. 5

p. 5The first opera of any sort produced on American soil. The opera was first performed in Naples in 1699. It was staged in Spanish translation in Mexico City in 1711, and the text—both the original Italian and the translation on facing pages—was printed there some decades later.

Acquired 1907. Endowment funds.

An abstract of Geminiani's Art of playing on the violin, and of another ...

1769

-

p. 1

p. 1Geminiani was a notable composer and a violin teacher in London where this beginner’s handbook was first published in 1740. The publication of such a manual indicates that society in the English colonies had become sophisticated enough to allow an audience for secular music. The first professional musicians appear at about this time, as do the first American composers. This is the only known copy of the first music book of its kind printed in the United States.

jcbar 31:16-18; Roger P. Bristol, Supplement to Charles Evans’ American Bibliography, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1970, 3000; Colonial Scene, pp. 104-105. Acquired 1931. Endowment funds.

Templo de N. grande patriarca San Francisco de la Provincia de los Doze ...

1675

-

p. 19

p. 19The attempts of Italian humanistic architects to incorporate Neo-Platonic philosophy with Christian religion in building brought about a style that emphasized symmetry and light. The wave of Spanish friars who set out for Mexico in the 1520’s had acquired the humanistic ideas which spread from Italy. They supervised the construction of humanistic Italian-style churches throughout Spanish America. There was a moral, as well as aesthetic, consideration to this architecture. Christian public architecture—as in cathedrals —was designed to contain spiritually and physically the entire population of the area it served. In contrast, the Aztec temples were reserved for the priests and their victims.

One of the great monuments of humanistic architecture in America is the cathedral of San Francisco in Lima. Our copy of the book describing the dedication of this cathedral in 1675 contains the only known engraving showing the entire church.

Medina, Lima, 496; Humberto Rodriguez Camilloni, “Architectural principles of the Age of Humanism applied,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, xxviii, Dec. 1969, pp. 235-253; Humberto Rodriguez Camilloni, “El Conjunto monumental de San Francisco De Lima en los siglos XVII y XVIII,” in Boletín Del Centro De Investigaciones Históricas y Estéticas, xiv, Caracas, Venezuela, 1972, pp. 31-60. Acquired 1968. Louisa Dexter Sharpe Metcalf Fund.

XIII. Jesuits from America Exiled to Italy

Saggio sulla storia naturale della provincia del Gran Chaco

1789

-

p. 1

p. 1A Catalan, Jolis had served in Paraguay for ten years when he was forcibly removed. In 1767 he settled in Faenza in the Papal States. He planned a four-volume study of the Gran Chaco—the great lowland plain now shared by Paraguay, Argentina, and Bolivia—from which his order had been removed. He published only the first volume, rich in detailed anthropological information about native life and customs.

jcb (1)3:3288; Sabin 36411; Backer 4:812; Streit 3:1118. Acquired before 1870 by John Carter Brown.

Storia antica del Messico

1780-1781

-

p. 7

p. 7Clavijero was a native of Veracruz, Mexico, who taught rhetoric and philosophy at the University of Mexico before being exiled. In his enforced idleness, in the small city of Cesena in Romagna, he studied the early history of his country.

His four-volume study of pre-conquest Mexico developed themes laid down by Boturini Benaducci and was an important step in the scientific study of Aztec civilization. The illustrations depicted an Aztec temple, studied from ruins, and dress and religious rites, derived from manuscript records.

jcb (1)3:2629; Sabin 13518; Backer 2:1210; Gerbi, Dispute, pp. 196-211. Acquired before 1870 by John Carter Brown.

Saggio di storia americana o Sia storia naturale, civile, e sacra de reg...

1780-1784

-

p. 7

p. 7A native of Spoleto, Gilii had spent eighteen years in a mission to the Orinoco region before being forced home. The four volumes he wrote during his exile are basic for the history of Venezuela. The first volume deals with geography and natural history, the second with native customs, the third with religion and language, and the fourth with the current situation in the area. King Charles III of Spain awarded Gilii a pension for his work.

The illustrations for the book are an important record of native life on the South American frontier. The artist’s classical training gives the figures an appearance more likely to be encountered in the Roman Forum than the jungles of the Orinoco, but the information conveyed is accurate.

jcb (1)3:2648; Sabin 7382; Backer 3:1415-16; Gerbi, Dispute, pp. 223-233. Acquired before 1870 by John Carter Brown.

XIV. Italian Awareness of English America, 1770-1755

Descrizione geografica di parte dell'America settentrionale

1758

-

p. 1

p. 1In this pamphlet and its map the stakes of the rivals for empire in North America are laid out. We believe it to be the work of the French cartographer Beilin who wrote a series of pamphlets in French with similar titles.

Although we know of no other copy of this pamphlet, nor of a French original for this one, it fits Beilin’s pattern of publication. It was not unusual at this time for works in Italian to be printed at Amsterdam and sold by booksellers in Venice.

Acquired 1911. Endowment funds.

Compendio della guerra nata per confini in america tra la Francia e l'In...

1763

-

p. 1

p. 1The Seven Years’ War or, as it was known in America, the French and Indian War, changed the balance of power in Europe. Badia asks who could have imagined that France and England would fight such a ferocious war throughout the world simply over America? And who could have imagined that Britain and Prussia alone could so decisively defeat the combined powers of France, the German Emperor, Austria, Sweden, Russia, Saxony, and Spain? The growth of America had unbalanced the centuries-old power structure of Europe, and even more changes were to follow. Italian readers must have been deeply concerned about how this affected them.

This work appears to be Venetian printing: the Amsterdam imprint is probably false and is presumably a cover to protect the actual printer. As the losers in this war were powers that dominated Italian politics, frank discussion of the war would have been a delicate matter.

Sabin 2709. Acquired before 1900.

La storia dell'anno

1730-1810

-

p. 1

p. 1Italians obtained some American news from newspapers and from publications such as this annual survey of the events of the preceding year.

The Library has fifteen of these from different years, the first printed in 1741, the last in 1796. In this issue the commercial disadvantages placed on Americans are explained as part of the reason for colonial unrest in 1769.

Acquired 1975. The gift of Mrs. Roger Amore Laudati.

Lezioni di commercio o sia D'economia civile

1769

-

p. 1

p. 1Antonio Genovesi was Professor of Economics at the University of Naples, the first professorship in that field ever established. He trained a generation of students who served King Charles III in Naples, Spain, and the New World. Genovesi’s book, first published at Naples in 1766, is filled with American examples which display a deep familiarity with the literature on America.

Perhaps most interesting is his projection that, at the current rate of growth, the wealth of England’s and Spain’s American colonies would outstrip that of the metropolitan countries. Then, he suggests, as it is unnatural for the greater to be dominated by the lesser, surely the Americas will have to become independent.

Pace, Franklin, p. 125; Kenneth E. Carpenter, Economic Bestsellers before 1850, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1975 - Acquired 1975. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

Précis de l'état actuel des colonies angloises dans l'Amérique septentrionale

1771

-

p. 5

p. 5This book is a plagiarism, published by Dominique Blackford, of the Anmerkungen (the notes) of Gottfried Achenwall, a professor at Gottingen University. Achenwall had interviewed Benjamin Franklin during the latter’s visit to the Gottingen in 1766. The results of the interview, the Anmerkungen, were published in the Hannoverisches Magazin in three installments in 1767 and then published separately in 1769.

Blackford presented the translated text as his own, and it was widely reviewed in Italian magazines. The book included a copy of Benjamin Franklin’s testimony on the Stamp Act in America before the English House of Commons in 1766, and introduced the arguments of the American patriots to Italy. While the libertarian pamphlets published by Americans were well received in certain circles, few were translated into Italian or printed in Italy. Most Italian intellectuals knew them from French translations, if not from the original English.

Leonard N. Beck, “Dominique de Blackford: Plagiarist, Bibliographical Society of America, Papers, vol. 68 (1974), pp. 427-432; Pace, Franklin, p. 124; Sabin 5691. Acquired 1946. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

Istoria del governo d'Inghilterra

1776

-

p. 1

p. 1This book was one of the first histories of the American Revolution. Martinelli, a prominent Florentine writer who had known Benjamin Franklin in London, appreciated the Americans’ patriotic motivation. He combined such notions as Pennsylvania being the realization of a poetic Golden Age with more realistic assessments of America’s resources. In his judgment England was involved in a war in which they could suffer shameful losses and could gain only lamentable victories.

The book was reprinted at Pescia, near Lucca, in 1777.

Pace, Franklin, pp. 168, 238-239. Sabin 44946 is the Pescia edition. Acquired before 1900.

Storia dell'America Settentrionale

1778-1780

-

p. 1

p. 1The most widely-read author on America during the years after 1770 was the Abbe Raynal. He never traveled to America, but he believed that the discovery of America had been “both the most important and most disastrous event in the history of civilization.” In this spirit, he compiled an encyclopaedic work, Histoire Philosophique et Politique…, which first appeared in Amsterdam, 1770. With revisions and additions, the work went through many editions in French and was translated into various European languages.

The book was controversial on many grounds. His strong opposition to colonies aroused leaders of colonial powers against him. His theory that the climate of America caused plants, animals, and people to deteriorate into inferior forms inspired replies by many Americans from Jefferson of Virginia to Jose Hipolito Unanue of Lima.

The Venice edition is an Italian translation of the seventeenth and eighteenth books of Raynal’s second version of the text first published at The Hague in 1774. This is the portion of the book that dealt with British North America. Most of Raynal’s book dealt with Spanish America, and the sources of his theories were Spanish. Antonio Zatta chose to publish that part of the book which had topical interest. Zatta published a number of geographical works, including an atlas with a special section of North American maps, and other Americana during the succeeding twenty-five years.

Acquired 1972. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

Stato presente della nazione inglese

1775

-

p. 1

p. 1William Knox had been Governor of Georgia, an agent in London for several colonies and Under-Secretary of State for America during the years 1770 to 1782. He knew the American situation intimately, and as relations between England and her colonies deteriorated during the Stamp Act crisis he wrote a gloomy appraisal of Britain’s financial situation, The Present State of the Nation, first published in London, 1768. His forty-eight-page pamphlet went through four editions in London and one in Dublin and generated controversy: it was attacked by Edmund Burke among other English writers.

Knox’s pamphlet had unusually wide circulation abroad: the John Carter Brown Library has three Spanish editions (of 1770, 1771, and 1781) and a French edition of 1769. As this catalogue was in the final stages of preparation the Neapolitan edition of a translation became available. The translator, Michele Torchia, added to Knox’s modest work, expanding it into two volumes of over 350 pages, and dedicated it to Marchese Bernardo Tanucci, the Tuscan Regent of Naples. In Torchia’s hands the book became a plea for free trade in the kingdom. Torchia was well versed in the English system and the important role the American colonies played in the system.

His additions include more American material: the second volume includes the memorial from the Continental Congress of 5 September 1774 to the people of Britain in which the plight of the colonists is presented directly to the populace.

Kress Library of Business and Economics, Harvard University, Catalogue, Boston, 1940, 7126. Acquired 1979. The gift of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel J. Hough to honor Mr. and Mrs. Vincent J. Buonanno.

Il Gazzettiere americano

1763

-

p. 1

p. 1This is a translation of an anonymous English book, The American Gazetteer, published in London by Andrew Miller the previous year. The translator is not known, but he faithfully rendered the English into Italian. A comparison of the entries shows that although the words were translated literally the printer, Marco Colteliini, has elevated the cramped, unattractive English original into a handsome book, and the visual effect of the Italian edition is strikingly superior.

Because it is a translation of an English work, there is much more information about the English colonies in America than is found in most geographical books written by continental authors up to this time.

jcb (1)3:1355; Sabin 26814. Acquired before 1870 by John Carter Brown.

XV. Benjamin Franklin and the Italians

Memorie istoriche intorno gli studi del padre Giambatista Beccaria

1783

-

p. 1

p. 1Franklin’s connection with Italian scientists is represented by this biographical notice of Father Giambatista Beccaria, professor at the University of Turin.

Beccaria had responded to Franklin’s electrical experiments by conducting a series of important experiments himself. Letters exchanged between Franklin and the learned Beccaria are appended to this work.

Pace, Franklin, p. 418, n. 50. Acquired 1974. Louisa Dexter Sharpe Metcalf Fund.

Scelta di lettere e di opuscoli

1774

-

p. 5

p. 5This first selection of Franklin’s scientific works to appear in Italian was taken from the French Oeuvres, published in Paris, 1773, by Barbeau Dubourg. The Italian translator, Carlo Giuseppe Campi, dedicated the collection to Count Carlo Giuseppe Firmian, the Governor of Lombardy, explaining that his motive was to make “better known to the world the name, the merit, and the teachings of this great philosopher.”

Ford (Franklin) 321; Pace, Franklin, p. 45, n. 12. Acquired 1920. Endowment fund.

Opere politiche di Beniamino Franklin L.L.D. F.R.S

1783

-

p. 1

p. 1This collection was translated by the Venetian abbot Pietro Antoniutti from Benjamin Vaughan’s edition of Franklin’s Political, Miscellaneous, and Philosophical Pieces, London, 1779. It marks a turn of Italian interest in Franklin: there was more interest in his political writings than in his earlier scientific works as a result of increased awareness of the significance of the American war.

Ford (Franklin) 343; Pace, Franklin, p. 128. Acquired 1968. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

Descrizione della stufa di Pensilvania inventata dal signor Franklin americano

1788

-

p. 1

p. 1Italians were very interested in Franklin’s stove. In 1767 Leopold, Grand Duke of Tuscany, sent Filippo Mazzei to London to purchase one. Franklin himself helped Mazzei obtain a correctly made version, and as a consequence the first authentic Franklin stove in Europe was to be found in Florence. Word of its effectiveness spread, and soon the stoves were available in Milan, Venice, and other cities. The Venetian printer Antonio Graziosi first published this pamphlet in 1778 and brought out editions of 1781,1788, and 1791 (of which the Library has the last two), besides advertising it annually in his newspaper, Notizie del Mondo.

Pace, Franklin, p. 76, cf. p. 417, n. 35; cf. Ford (Franklin) 42. Acquired 1958. Associates of the John Carter Brown Library.

Avviso a quegli che pensassero d'andare in America

1785

-

p. 1

p. 1This is a translation of Franklin’s Two Tracts, London, 1784, which included "Information to Those who Would remove to America” and “Remarks concerning the Savages of North America.

Franklin composed the first tract to discourage “misfits” from coming to America, including artists, office-seekers, soldiers, and nobility. America was for those who were willing to work. The second tract pictured Indians as simple, virtuous people of common sense. Two different Italian translations were published in 1785, this one by the Cremonese printer Lorenzo Manini.

Pace, Franklin, p. 140. Acquired 1972. Lathrop Colgate Harper Fund.

Il buon uomo Ricciardo e La costituzione di Pensilvania

1797

-

p. 7

p. 7The European political struggles of the 1790’s put tremendous pressure on all the Italian states and caused the structure of the Venetian oligarchy to collapse. For a brief time a democratic government was proclaimed, but in 1797 the French and, later, the Austrians installed their own oppressive rule over the city. In the brief period when democratic aspirations flamed, two young patriots published this book. It translates the aphorisms Franklin had published in his almanacs and the Constitution of Pennsylvania (which Franklin had helped to write) for the use of the restoration of Venetian democracy. The political examples of Franklin and of Pennsylvania offered a promise the Venetians were unable to realize for three generations.

There is no copy of this book known to be in another American library, and only two have been identified in European collections.

Pace, Franklin, p. 421, n. 87. Acquired 1977. Anonymous gift to honor Senator John H. Pastore.

XVI. Italian Contributions to American Political Thought

An essay on crimes and punishments

1778

-

p. 1