The Book and Printing in Spanish America

The Audiencia of Mexico

Dotrina breue muy p[ro]uechosa delas cosas q[ue] p[er]tenecen ala fe cat...

1544

-

p. 5

p. 5Juan de Zumárraga, the Franciscan friar who went to Mexico City as its first Bishop in 1528, was instrumental in the introduction of the printing press into the Spanish American colonies.

Religious materials were urgently needed for the conversion of the natives, and European printers were ill-equipped to handle manuscripts in Indian languages. At the Bishop’s insistence, Juan Cromberger established a branch of his Sevillian publishing house in Mexico City and shipped to the New World all the equipment and supplies vital to its operation.

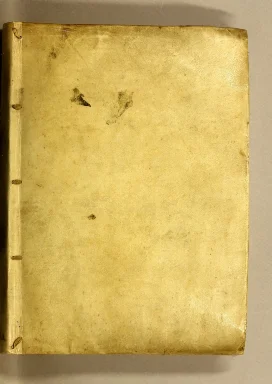

Juan Pablos (d. 1560), a native of Brescia, Italy, became Cromberger’s Mexican agent and later the owner of the press on which he printed the 1539 edition of the Breve y mas compendiosa doctrina Christiana en lengua mexicana y castellana, the first American book.

Today, the 1544 edition is the earliest example of a book printed by Pablos’s press in American collections.

Tripartito del christianissimo y consolatorio doctor Juan Gerson de doct...

1544

-

p. 5

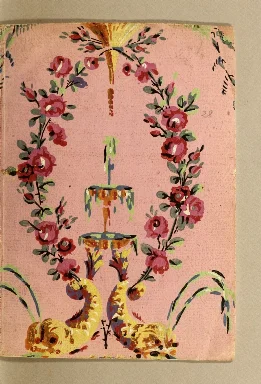

p. 5The Inquisition was established in Lima in 1570 and in Mexico City in 1571, becoming the primary agency for judging the acceptability of manuscripts and books, and also serving as a court to hear cases when laws were broken. Prior to its establishment, censorship of the press in colonial Spanish America was the responsibility of both civil and ecclesiastical authorities. Permission to publish was obtained from the Church's highest-ranking official in the viceroyalty. As stated on the title page of the Tripartito, the volume was reviewed and approved by order of Bishop Zumárraga. The publishing house is given as the "Casa de Juan Cromberger," a custom that would be maintained in the printing of the colophon until 1548.

This translation of Gerson's work, which first appeared in Latin in 1467, is another example of Juan Pablos's printing. The book is notable because it contains the first full-page book illustration, following a European format, printed in the New World. Due to the scarcity of such woodcuts, this one was used again by other early Mexican printers. The verso of the title page depicts a scene in which Saint Ildefonso receives the chasuble from the Virgin Mary.

Phisica, speculatio

1557

-

p. 5

p. 5Mexico’s first printer produced other secular books, including three Latin academic texts either written or edited by the distinguished Augustinian teacher, scholar, and book collector, Fray Alonso de la Vera Cruz. He was the first professor to occupy the chair of scholastic theology at the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico, having been appointed to that position in 1553, the year in which the institution opened its doors. His Phisica, speculatio is believed to be an original work, the first presenting European concepts of physical science to be printed in the Americas. Aristotle’s Dialectica resolutio, one of two other texts bound in this volume, is the earliest translation of a Classical author’s work to be published in the New World (fig. 7). Only two copies of this translated work are recorded in the United States. The marginalia, appearing throughout the John Carter Brown copy, are in the churchman’s own hand and contain additions and corrections made in the subsequent editions published in Salamanca.

Regionum Indicarum per Hispanos olim devastatarum accuratissima descrptio

1664

-

p. 23

p. 23Las Casas’s version of Spanish atrocities in the New World had considerable impact on international politics, and his account was used by Spain’s enemies as the basis for the “black legend” excoriating Spanish cruelty. Editions of the Brevissima relation were translated and published in France, Holland, England, and Germany, some with detailed illustrations of horrifying violence, which helped to justify intervention by other nations in the Western Hemisphere. This Latin edition, published in Frankfurt, is a translation of Tyrannies et cruautez des Espagnols (Antwerp, 1579), itself a translation of the Brevissima Relación.

Among the shocking scenes depicted in this edition is the massacre of Queen Anacaona and her subjects. After an elaborate reception celebrating the arrival of Nicolas de Ovando (Christopher Columbus’s successor as governor of Hispaniola), members of the Queen’s entourage were burned alive; in deference to her rank, she was hanged. When word of the incident reached Spain, Queen Isabella herself was among those who expressed their sorrow at the fate of the Indians.

Among the shocking scenes depicted in this edition is the massacre of Queen Anaca- ona and her subjects. After an elaborate reception celebrating the arrival of Nicolas de Ovando (Christopher Columbus’s successor as governor of Hispaniola), members of the Queen’s entourage were burned alive; in deference to her rank, she was hanged. When word of the incident reached Spain, Queen Isabella herself was among those who expressed their sorrow at the fate of the Indians.

[Catecismo Testeriano]

-

p. 12

p. 12Father Jacobo de Testera, a sixteenth-century churchman, wished to create the best possible atmosphere for the rapid conversion of Mexico’s natives to the Christian faith. In order to eliminate the need for immediate language training for both Indians and friars, he devised a unique form of picture-writing in which to present religious materials. When the names of the objects depicted were spoken aloud in the indigenous language, the sound approximated that of the Latin words of prayers and portions of the Mass. This manuscript booklet of thirteen leaves is one of three Testerian catechisms in the John Carter Brown Library.

Dialogo de doctrina christiana, enla lengua d[e] Mechuaca[n]

1559

-

p. 14

p. 14Fray Maturino Gilberti was a colleague of Father Jacobo de Testera and one of the most illustrious Franciscans to dedicate himself to the conversion of Mexico’s Indians. Known as the “Cicero of Tarascan” (the Indian language of Michoacán), he wrote numerous works of religious and linguistic importance. His 1558 Arte de la lengua de Michuacan, of which the John Carter Brown Library has the only copy in the United States, was the first grammar of an Indian language published in the New World.

The publication of his Dialogo de doctrina Christiana in Tarascan became enmeshed in questions about the accuracy of the translations, and all copies were confiscated by order of the bishops. Spain’s first real Index of forbidden books, published the same year as Gilberti’s work, warned against the circulation of Christian doctrine in languages other than Latin. Although the Inquisition was not established in Mexico until 1571, this problem would be one of the first to be considered by its judges.

[Diccionario de Motul, maya español]

1577-1630

-

p. 7

p. 7The Mayan civilization, which emerged around 1500 B.C., extended eventually from Yucatan to Western Honduras. A sophisticated architecture, sculpture, painting, mathematics, and astronomy are among the Mayas’ cultural and intellectual achievements, and they were responsible as well for devising an early system of writing antedating the European conquest of the Western Hemisphere. At the peak of their civilization, Mayan scribes routinely prepared folded screens of paper made from bark, inscribing them with pictographs and ideographs recording various aspects of their daily life. Believing that these manuscripts were the works of the devil, Cortés and his soldiers destroyed many of them in the first book-burnings carried out by the Spaniards in the New World.

The “Diccionario de Motul” was compiled to help Spaniards communicate more effectively with the descendants of the great Mayan people. The lexicon demonstrates that the friars used a number of indigenous words having to do with books. Centuries later, it was a source of information for archaeologists who excavated the ruins at Chichen Itzá.

Psalmodia christiana, y sermonario de los sanctos del año, en langua mexicana

1583

-

p. 5

p. 5Another outstanding Franciscan who came to the New World to advance the goals of Indian conversion was Father Bernardino de Sahagún. As a Latin teacher, he began instructing natives at Tlatelolco’s Colegio de Santa Cruz in 1536, the year it opened. As a historian, he won acclaim for his Historia general de las cosas de Nueva Espana, which contains a detailed account of the daily life and customs of the Aztecs and other indigenous peoples of Central Mexico. During the course of his missionary duties, he wrote numerous religious works, but only a few were published.

Among Sahagún’s obras in the John Carter Brown Library is the printed hymnal entitled Psalmodia Christiana. It consists of a collection of psalms written in Nahuatl which were to be performed in areitos or brief dramatic interludes. As Fray Toribio Motolinía (d. 1568) attests in his Historia de los indios de la Nueva Espana, dramatic representations were an important instructional tool used by the friars in the evangelization of the Indians. The Psalmodia Christiana, only three copies of which are recorded in the United States, was published by Pedro Ocharte, Mexico’s third printer and the son-in-law of Juan Pablos. Because he allegedly praised a work denying the intervention of saints, Ocharte became one of the first victims of the Inquisition in Mexico City.

8a Tozi que quiere dezir aguela. Diosas de los Mexicanos

1492-1600

-

p. 1

p. 1Based upon a history of the Aztecs by the Dominican Diego Durán, Tovar’s Historia de la benida de los yndios (also known as Tovar Codex) contains detailed information about the rites and ceremonies of the Aztecs, an elaborate comparison of the Aztec year with the Christian calendar, and the correspondence between Tovar and the Jesuit Father Jose de Acosta. A copy of Tovar’s history was sent to Acosta in Peru, and he used it as an important source for his own history of the Indies.

This history appears to be a holograph, and it is illustrated with fifty-one full-page paintings in watercolor. Strongly influenced by Aztec picture-writing, they are of exceptional artistic quality. Among the renderings are representations of Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and principal deity of the Aztecs, and Quetzalcoatl, the Toltec king-god who had been incorporated into the Aztec religious hierarchy. Several of Moctezuma’s advisors believed that Hernán Cortés was the peaceful Quetzalcoatl, who had returned from the East to lead his people as he had promised. The motif of the plumed serpent, Quetzalcoat's symbol, graces many monuments of the Toltec, Maya, and Aztec civilizations.

Dos libros

1565

-

p. 1

p. 1The natural environment of the New World fascinated early scientists, many of whom came to the Indies during the colonial period. They were particularly intrigued by the unusual vegetation and searched for plants with medicinal properties. After collecting seeds in New Spain and growing them in his garden in Seville, the botanist Nicolás Monardes composed this work on American herbs and drugs, which would constitute a major step in the history of medical science.

Although many of the curative agents that he gathered and tested, such as guaiacum wood and the bezar stone, failed to prove effective against Old World diseases, some, like quinine and ipecac, continue to play a role in modern pharmacology. Only three copies of this work are recorded in the United States.

Ioyfull newes out of the newfound world

1580

-

p. 5

p. 5By the end of the sixteenth century, Monardes’s medical treatise had appeared in seventeen different editions in four languages. This English translation was done by John Frampton, and its tide is an indication of the enthusiasm with which the botanist’s study was received. Frampton, an English merchant, had spent years in a Spanish prison by order of the Inquisition. He allegedly undertook this assignment to interest his own countrymen in tapping the vast wealth of the Americas.

Quatro libros. De la naturaleza, y virtudes de las plantas, y animales q...

1615

-

p. 7

p. 7This abridged and translated version of the medical information contained in Francisco Hernández’s twenty-volume Latin manuscript on the natural history of New Spain is the earliest work published in the New World describing the medicinal value of native plants.

Hernández was the personal physician of Philip II and was named Protomedicus of New Spain in order to carry out a scientific study of the viceroyalty’s plants, animals, and minerals. After his arrival in 1570, he began gathering specimens and testing their various properties. In addition to compiling the results of his experiments, he asked native artists to illustrate his work. The coloring of these illustrations was reported to be of extraordinary quality because of the artists’ desire to be as realistic as possible.

In 1577 Hernandez took one completed set of his volumes back to Spain where he hoped to have his work published. Unfortunately, however, the manuscript was simply bound and placed in the library of the Escorial, and the illustrations were hung on the monastery’s walls. In the fire of 1671 both the text and the original drawings in color were damaged. Woodcut illustrations, supposedly derived from Hernández's original drawings, appear in Juan Eusebio Nieremberg’s Historia Naturae, published in Antwerp in 1635 (figs. 21, 22, 23, and 24).

Ortografia castellana

1609

-

p. 7

p. 7A number of Spanish writers were attracted to the New World, and they wrote and published their works throughout the colonies. Among them was Mateo Alemán, author of the famous picaresque novel Guzmán de Alfarache. In 1599 the first part of this masterpiece was published in Madrid and enjoyed more immediate success than Cervantes's Don Quijote.

In an effort to protect newly-converted Indians from frivolity, the Spanish crown at first sought to prohibit the importation and publication of works of pure fiction such as Guzmán de Alfarache. Although initially banned from the Americas, the Guzmán was shipped to the New World in quantity during the early years of the seventeenth century, according to extant ship manifests.

Works of instruction were more acceptable than novels, and the authorities readily permitted Alemán’s treatise on peninsular orthography (fig. 25) to be produced by the family of Mexico’s fourth printer, Pedro Balli. By the time Aleman published more of his writings, Balli’s widow, Catalina del Valle, was in charge of the business. In the Spanish American colonies, the widows of printers often assumed entrepreneurial duties. In Mexico, the tradition was begun in 1594 by María de Sansoric, who began work on the printing of Father Manuel Alvarez’s De institutione grammatica after the death of her husband, Pedro Ocharte.

Sucesos de D. frai Garcia Gera arcobispo de Mejico, a cuyo cargo estuvo ...

1613

-

p. 12

p. 12On August 9, 1608, Fray García Guerra (1560-1612) arrived at the port of Veracruz to assume his position as Archbishop of the New World’s wealthiest see, and in 1611 he became Viceroy of New Spain as well. The major events of his tragically short tenure as Archbishop-Viceroy were documented in this account by Mateo Alemán, who accompanied the eminent Dominican to the Indies.

When Alemán arrived in the New World, his copy of Don Quijote was confiscated by inspectors of the Holy Office of the Inquisition. Such measures, however, did not stop the flow of creative and imaginative works to the colonies, and Aleman’s book was later returned to him.

Only two copies of Alemán’s account of Fray García Guerra’s residence in Mexico are recorded in the United States.

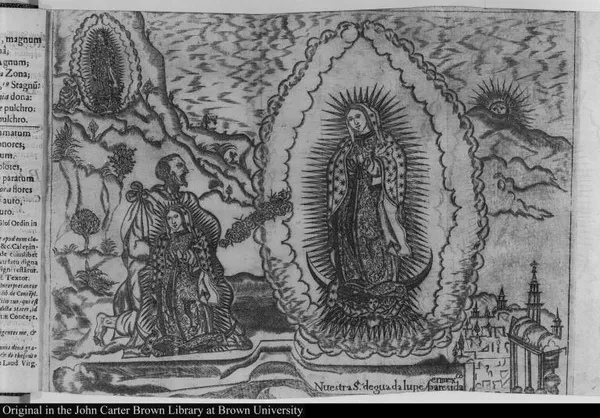

Neustra S. de guadalupe aparesida en mex[i]co

1651-1700

-

p. 1

p. 1The Virgin of Guadalupe, whose apparition aided sixteenth-century friars in the conversion of Mexico’s Indians, became increasingly popular as an object of adoration throughout the colonial period. Early in the nineteenth century, revolutionary forces rallied around her image, and she is a contemporary symbol of the country’s religious devotion. In his Felicidad de México, Luis Becerra Tanco describes the circumstances surrounding the miraculous appearance of the Virgin with Indian features and the efforts of Juan Diego, a native laborer, to fulfill her request by having a shrine built in her honor. Juan Diego reportedly experienced her presence on the hill of Tepeyac near the site of the temple to the Aztec goddess Tonantzin. Bishop Zumárraga was reluctant to believe Juan Diego’s story but finally accepted his mantle with the Madonna’s semblance on it as proof of her divine intervention.

The portrait of the Virgin of Guadalupe was duplicated many times by early Mexican printers. This particular one, influenced more by European artistic traditions than by native American images, was the nineteenth known to have been printed in Mexico. It is eloquent testimony to the capacity of printers and engravers in seventeenth-century New Spain to produce excellent work.

Only two copies of this book, the second edition, are recorded in the United States. The first edition appeared in 1666 under a different title.

Exposicion astronomica de el cometa, que el año de 1680. por los meses ...

1681

-

p. 5

p. 5The great comet, which appeared over New Spain in 1680—1681, sparked an intense controversy between the Tyrolean Jesuit, Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, and the Creole savant, Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Gongora, over its significance for New World residents. Their arguments constitute the first intellectual debate to appear in print in the Indies over a matter of scientific importance based on local experience. The clash is symbolic also of the ongoing conflict between superstition and science.

Father Kino, later a well-known missionary and explorer of northwestern New Spain, held the traditional view that the comet was an ominous warning of divine origin, sent by God to announce His displeasure and to foretell punishment. Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Gongora opposed Father Kino’s obscurantist interpretation and sought to dispel the fear surrounding the occurrence by gathering scientific information about the comet itself.

Carta athenagorica

1690

-

p. 1

p. 1In 1690 Sor Juana wrote an eloquent and erudite challenge to a sermon delivered many years earlier by the Portuguese Jesuit, Antonio Vieira. Her rebuttal came to the attention of Puebla’s Bishop, Don Manuel Fernandez de Santa Cruz, who was so impressed by her scholarship that he had it published under the title Carta Athenagorica. The correspondence that accompanied the printed copy sent to Sor Juana praised her for this intellectual achievement but criticized her for not devoting her energy exclusively to religious endeavors.

Months after Sor Juana received the Bishop’s letter, she responded to his criticism in her now famous Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz. In this reply, she traces the development of her “inclination toward study” to her childhood when she learned to read at the age of three, won her first prize in a poetry competition five years later, and dreamed of attending the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico. This institution of higher learning was closed to women, however, and even Sor Juana’s offer to dress like a man could not gain her admission. In her youth, before she became a nun, she had been a member of the viceregal court and had written many secular works for her illustrious admirers. Because her Respuesta also contains a defense of women’s right to intellectual freedom, Sor Juana is often considered to be America’s first feminist.

[Codex Santa María Tetelpan]

1700-1748

-

p. 1

p. 1Pictorial manuscripts using indigenous techniques were still being made two hundred years after the conquest, and some were prepared as forgeries of original tides to property. This codex of fourteen leaves, usually classified as belonging to the Techialoyan group of writings, is a land claim prepared by residents of Mazatepe, an Indian village whose boundaries were being challenged by the authorities. By using native amatl paper derived from fig tree bark, and by combining watercolor paintings with glosses written in Nahuatl, the forgers endeavored to imitate sixteenth-century documentation of landholdings.

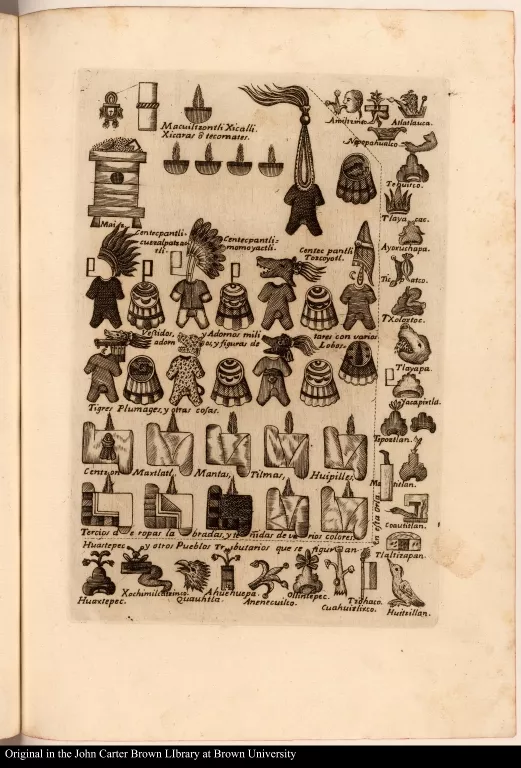

[Aztec Tribute List]

1751-1800

-

p. 1

p. 1Francisco Antonio de Lorenzana y Buitron (1722—1804) was among the most brilliant clerics to serve as Archbishop of Mexico, a post that he occupied from 1766 to 1772. Before returning to the Iberian peninsula, he amassed an important collection of manuscripts relative to New Spain, housed today in Toledo’s Biblioteca Publica. Among his many contributions to New Spain’s history is this edition of the letter-reports of Cortes, which also contains records of tribute paid by various Mexican settlements to Mocte- zuma, and an account of the voyage of Cortes to California in 1535.

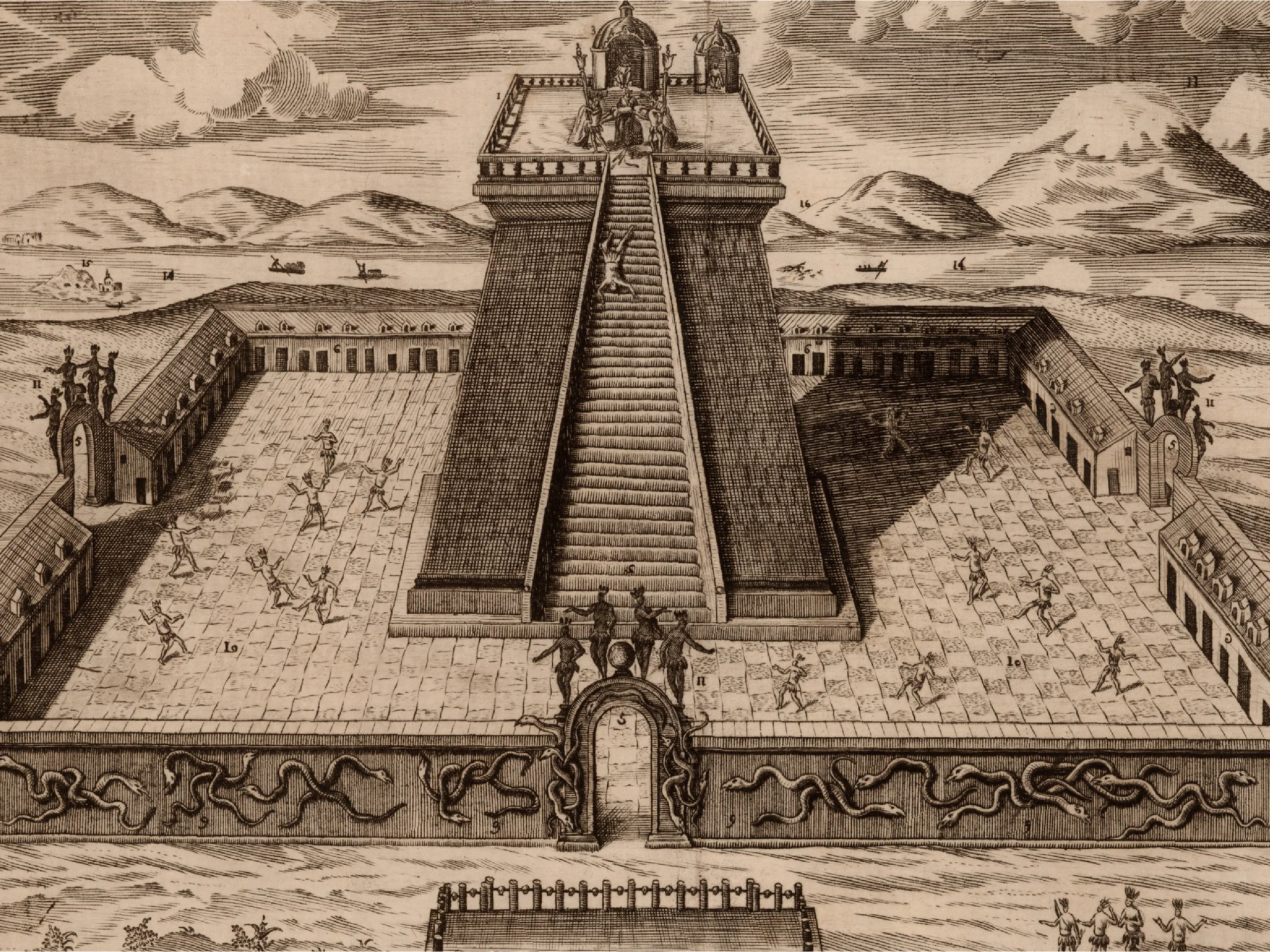

Typographically, the Historia de Nueva-Espana is one of the finest products of the press of Joseph Antonio de Hogal (1766-1787), and it is particularly notable for its excellent copper engravings. The map of New Spain, view of the Great Temple of Mexico, frontispiece, and Domingo de Castillo’s map of California were executed by José Mariano Navarro, an engraver and binder ofMexico City. Manuel de Villavicencio produced the Mexican calendar and thirty-one plates depicting the tributes paid to Moctezuma.

Missa Gothica seù Mozarabica

1770

-

p. 1

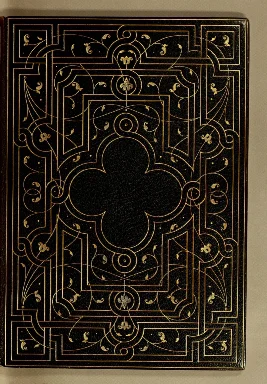

p. 1Among the earliest imprints of the Real Seminario Palafoxiana of Puebla is the Missa Gothica, a tour de force of graphic arts dedicated by the Bishop of Puebla, Francisco Fabian y Fuero, to his godson, Francisco Antonio de Lorenzana y Buitron. The Mozarabic rite of the Mass was authorized in the fifteenth century by the Cardinal Primate of Spain and Archbishop of Toledo, Francisco Jimenez de Cisneros, for use only in certain churches in the city of Toledo by those Christians who had been captives during the Moslem occupation. The publication of this liturgy in New Spain, however, did not authorize its use there.

The work is notable for its beautiful red and black title page and for its five extraordinarily fine copper engravings. The latter were executed by José de Nava, a native of Puebla (1735-1817), who was considered one of the finest engravers of his time. Apart from its physical beauty, this book is of historical interest as one of the few surviving texts of this rare and restricted rite of the Mass.

The Captaincy-General of Guatemala

Relacion de la vida, y virtudes del V. hermano Pedro de San Ioseph Betan...

1667

-

p. 5

p. 5In 1660, at the insistence of Guatemala’s Bishop, Fray Payo Enriquez de Ribera, Joseph de Pineda Ibarra (1629-1680) moved his printing press from Puebla de los Angeles near Mexico City to Central America. The printer’s son eventually took over the family business, which would remain Guatemala’s sole publishing house until 1714. This example of Pineda Ibarra’s work is the only known complete copy of Manuel Lobo’s account of Brother Betancur’s efforts to convert the Indians of Guatemala and to establish the Convalescent Hospital of Our Lady of Bethlehem in Guatemala City.

Thomasiada al sol de la iglesia, y su doctor santo Thomas de Aquino

1667

-

p. 5

p. 5Diego Saenz Ovecuri’s book-length poem, also printed by Pineda Ibarra, is believed to be the earliest literary work printed in Central America. In addition to being a poetic biography of St. Thomas Aquinas, the Thomasiada contains a treatise on the art of writing poetry. Only two copies of his work are known to be in the United States.

Noticia del establecimiento del museo de esta capital de la Nueva Guatem...

1797

-

p. 5

p. 5This museum booklet, printed for the institution’s opening, contains information about its establishment, the arrangement of its collection, and the inaugural address delivered on that occasion.

According to the description, the museum housed the rare collection made by the naturalist Jose Longinos Martinez. The naturalist had been sent by Charles IV to replace the specimens gathered by Francisco Hernandez that had been damaged by the 1671 fire in the Escorial.

Juana Martinez Batres, the widow of Sebastian de Arevalo, printed this booklet in the shop she inherited from him. She is credited with bringing three additional European presses to Guatemala during her management of the business. Her late husband had made significant contributions to printing by creating fonts that conformed to the Indian alphabet invented by Francisco de la Parra, and by publishing the Gaceta de Guatemala , the region’s first newspaper, from 1729 to 1731.

The Audiencia of Lima

Uerdadera relacion de la conquista del Peru y prouincia del Cuzco llamad...

1534

-

p. 5

p. 5On November 16, 1532, Spanish troops led by Francisco Pizarro entered the town of Cajamarca, Peru, to confront the Inca ruler Atahualpa and his subjects. The encounter is symbolic of the meeting of two worlds that had already taken place in Mexico and Central America and would soon be repeated throughout the South American continent. Pizarro’s secretary, Francisco de Xerez or Jerez, who was present at the time, offers a detailed description of the scene in his Verdadera relación de la conquista del Perú, one of the earliest accounts of the Spaniards’ conquest of the Inca empire.

An unknown European artist, drawing realistic elements from Xerez’s description and blending them with his own ideas about the New World, designed a woodcut for the first edition of the Verdadera relación. On the title page, Atahualpa holds what appears to be the Bible that was given to him by Fray Vicente de Valverde. Rejecting the incursion of foreigners into his kingdom and unaware of the importance of the sacred book, Atahualpa threw the Bible to the ground. The military clash that followed—and those provoked by similar encounters throughout the New World—changed forever the character of New World culture.

Parte primera dela chronica del Peru

-

p. 5

p. 5Early chroniclers, who witnessed the subjugation of Peru, wrote about the vast kingdom of Tawantinsuyu and offered the first European view of Inca civilization. Accounts such as this one by Pedro de Cieza de León contain valuable information about one of the world’s most successful empires and its people, a story that is only suggested by surviving artifacts.

Unlike the Mayans, the Incas never developed a system of writing, and knotted cords or quipus were the only formal means of making records.

-

p. 67

p. 67This autograph copy of Cieza’s chronicle is distinguished by its unusual woodcuts, which depict a European vision of America sometimes enhanced by fantastic elements. In one of them, the devil, believed to be hard at work in the New World, is shown as he keeps the inhabitants from leading a virtuous Christian life.

-

p. 258

p. 258In another, Lake Titicaca, located on the desolate Andean altiplano, looks curiously like a canal in the city of Venice

-

p. 268

p. 268The illustration of the Cerro de Potosi (fig. 50), the fabled “silver mountain” of the Indies, is an exception. Because it was based on an original drawing done by the chronicler himself, it more accurately depicts the real place.

Pragmatica sobre los diez dias del año

1584

-

p. 7

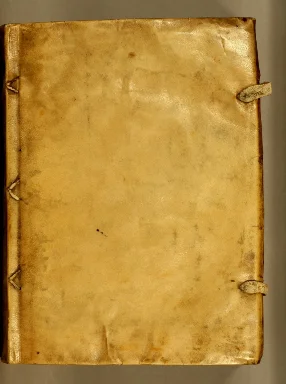

p. 7In 1580 the Italian printer Antonio Ricardo (d. 1605) left New Spain after a ten-year stay to establish the first printing press in Peru. He had been Mexico’s fifth printer and the producer of at least thirteen books in the viceroyalty’s capital. As the former partner of Pedro Ocharte, he owned much of the equipment used in their business, and with this he planned to set up shop in Lima. Whether Ricardo decided to move his press to Peru at the request of the Jesuits, in anticipation of the demand for books at the University of San Marcos, or in an effort to benefit from the prestige and affluence of viceregal Lima, his printing establishment was opposed by the authorities there, and he was unable to begin operating until 1584.

Ricardo’s first publication was to have been Doctrina Christiana. That project was interrupted, however, when word was received from Europe that Pope Gregory XIII had promulgated a change in the calendar requiring a one-time addition of ten days to the year. Europeans had observed the Gregorian calendar since 1582, and Ricardo’s Pragmatica announced its adoption to Spanish Americans.

The Pragmatica, a document of only four pages, was discovered among a group of other Peruvian pamphlets by George Parker Winship, Librarian of the John Carter Brown Library from 1904 to 1915. Close investigation revealed to Winship the extraordinary importance of the Pragmatica, and in 1912 he published a study in which he concluded that it antedated the 1584 trilingual edition of the Doctrina Christiana. This conclusion was later confirmed by José Toribio Medina. Only two copies of the work are known to have survived.

Tercero cathecismo y exposicion de la doctrina christiana, por sermones

1585

-

p. 5

p. 5The Jesuit Father José de Acosta (1539 — 1616) presided over Lima’s first Provincial Council, a meeting called in 1576 to evaluate the progress of Christian evangelization in Peru. Books, especially vocabularies, grammars, and catechisms in indigenous languages, were urgently needed by members of all the religious orders participating in the Council, and a request for a printer may have been a direct result of the proceedings. When Antonio Ricardo arrived, therefore, his principal duty was to print materials for proselytizing the Indians, and his earliest publications were closely supervised by Father Acosta. The Jesuit, who had become an expert in Andean languages, collaborated with the anonymous churchmen who wrote the first religious works produced on Ricardo’s press.

-

p. 5

p. 5Father Acosta personally checked volumes such as the Tercero cathecismo for accuracy, and his signature is the mark of approval.

The Tercero cathecismo was designed to instruct Indians who spoke two of the Peruvian viceroyalty’s principal languages, Quechua and Aymara, both of which are widely used today. This particular edition, with its Spanish version of the catechism, continues to facilitate the study of both American tongues. Early Lima imprints such as this are exceedingly rare.

Doctrina christiana y cathecismo en la lengua allentiac, que corre en la...

1607

-

p. 5

p. 5Lima’s press was later used to produce works for the conversion of Indians who lived beyond the borders of the old Inca empire. The Jesuit Father, Luis de Valdivia, who specialized in the native languages of Chile and Argentina, translated this doctrinal work for these nomadic Indians and formulated vocabularies and grammars for the friars who instructed them.

Unlike Quechua, which is still spoken by ten million South American Indians, Allentiac, the language of the inhabitants of the Argentine region of Cuyo, is now extinct. Only two copies of this work are known to be in the United States

Iosephi Acosta, Societatis Iesu, De natura Noui Orbis libri duo. Et De p...

1596

-

p. 5

p. 5In addition to being a guiding force in the religious conversion of Peru’s Indians, Father Acosta was a distinguished professor at Lima’s University of San Marcos. His comprehensive history of the Indies, first published in Salamanca in 1588, deals with the geography and natural history of the New World as well as the culture of its inhabitants. His detailed description of the customs of both North and South American Indians provides information about their religion, history, politics, and education, and he was one of the first historians to suggest that the native peoples of the Western Hemisphere came originally from Asia.

Ordenancas que el señor Marques de Cañete visorey, de estos reynos del...

1594

-

p. 7

p. 7Antonio Ricardo also printed a number of secular works, many of which deal with aspects of colonial administration. Among them is a set of ordinances approved by the Viceroy to stop the abuse of the natives by corregidores, or Indian agents. These minor officials played a critical role as liaison between the Spanish government and the Indian population, and they served as tax collectors, peace officers, and judges in indigenous communities.

Unfortunately, many corregidores viewed the office as a means of enriching themselves, and they demanded both goods and services from their Indian charges. Creoles, Spaniards born in the New World, were especially upset by the Ordenanças because the office of corregidor was one of the few imperial appointments for which they were considered eligible. At this time, appointments to government positions were routinely granted only to peninsular-born Spaniards.

The Ordenanças in the John Carter Brown Library is the only recorded copy of this work in the United States

Constituciones y ordenanças de la Vniuersidad, y Studio General de la C...

1602

-

p. 5

p. 5In 1551, Charles I authorized the establishment of a system of royal and pontifical universities in Spanish America, which were modeled on the University of Salamanca. Although the University of San Marcos, the constitution and laws of which are printed here, claims that its charter was signed before that of Mexico, the latter institution opened its doors to students in 1553, and was therefore the first to offer courses.

Ricardo printed the rules and regulations governing San Marcos, and these documents contain a description of its organization, administration, faculty, and curriculum (fig. 56). Because they were considered to be the University’s official policy, the constitution and ordinances were reprinted in Spain on several occasions.

This is one of only two copies of this work recorded in the United States.

Primera, segunda, y tercera partes de la Araucana

1590

-

p. 7

p. 7After the conquest of Peru, the Spaniards sought to extend the viceroyalty into northern Chile. Repeated incursions brought little immediate success against the area’s nomadic Araucanian Indians, but the epic poem by the soldier Alonso de Ercilla immortalized the campaigns and extolled the courage and skills of warriors on both sides (fig. 57). The elegance and precision of the poem’s royal octaves distinguish it among other Spanish epics, and the ideals it expresses are an aspect of Chilean national pride.

This is the first edition to incorporate all three parts of the work, the first part of which appeared in Madrid in 1569.

Only three copies of the complete 1590 edition are known to be in the United States.

Primera parte de Arauco domado

1596

-

p. 9

p. 9This epic poem written by Pedro de Oña, one of Chile’s first poets, was commissioned by the family of Don Garcia Hurtado de Mendoza in order to enhance his image as a military leader after he became Viceroy of Peru. As a young man, he led the campaigns against the Indians in Arauco, or Chile, but Alonso de Ercilla had failed to portray him as the hero of the expedition in his famous rhymed chronicle, La Araucana.

-

p. 15

p. 15Arauco domado was praised for its extraordinary artistry by the Spanish master, Lope de Vega. Printed by Antonio Ricardo, it is the earliest book of poetry written by an American author and published in the New World. This volume contains a portrait of Oña, believed to be the first locally prepared illustration to appear in a South American book. The woodcut was probably executed by Ricardo or one of his assistants.

Temblor de Lima año de 1609

1609

-

p. 7

p. 7The mountain ranges that extend through Mexico and Central America, and the Andes in South America, have been a constant source of seismic activity. Indian legends tell of the enormous destruction caused by earthquakes long before the arrival of the Spaniards, and they were the subject of colonial writing as well. An account of one that struck Guatemala City, published by Juan Pablos in 1541, was the earliest news report printed in the New World. In 1609, before newspapers had been established in Lima, Pedro de Oña wrote a poem describing the effects of a quake in that city.

Temblor de Lima was printed by Ricardo’s successor, Francisco del Canto, who produced his first work in 1605. He is credited with the introduction of two-color printing to the City of Kings, and it was under his imprint that books were published at Juli, the remote Jesuit mission near Lake Titicaca. Although Canto was not directly involved with the press in Juli, the name of his licensed publishing house on missionary publications probably exempted them from close scrutiny by ecclesiastical censors.

This copy of Temblor de Lima is apparently unique in the United States.

Primera parte de los commentarios reales

1609

-

p. 7

p. 7Descriptions of Indian culture and the conquest of the Americas were not the exclusive subjects of European historians and chroniclers. Accounts by Indians and mestizos such as Don Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl (1568-1648) in Mexico, and Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala (1526?-after 1613) and the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega in Peru, offer a new perspective on the people and events of the time and portray more vividly the clash of these different cultures.

In his Comentarios reales, the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega preserves the oral tradition of a civilization that achieved greatness in many respects but failed to develop a form of writing. As the son of an Inca princess and one of Pizarro’s soldiers, he heard his mother’s relatives recount the myths and legends of their heritage, and he recorded them in eloquent Spanish prose.

-

p. 109

p. 109In Chapter xv of the first book of the Comentarios reales, the Inca tells the story of the appearance of the first Incas and the founding of their empire. According to tradition, Manco Capac and his sister-wife Mama Ocllo were sent to earth by the Sun to establish their royal line. Leaving the shores of Lake Titicaca, they traveled in a northwesterly direction. With them they carried a gold rod, which would enter the ground at the exact location for the construction of their court, the future site of the city of Cuzco.

Templo de N. grande patriarca San Francisco de la Provincia de los Doze ...

1675

-

p. 3

p. 3The Catholic Church in the Spanish American colonies left many monuments that are indicative of its wealth and power in the New World. Among them is the convent church of San Francisco in Lima, an excellent example of Humanistic architecture inspired by Italian design. This book by Suarez de Figueroa describes the structure’s rededication in 1675 after earthquake damage had been repaired.

El Lazarillo de ciegos caminantes desde Buenos-Ayres, hasta Lima

1773-1776

-

p. 5

p. 5Inspired by the ideas of the Enlightenment, Charles III of Spain sought to reform the administration of the Spanish American colonies. In 1771, Alonso Carrio de la Vandera, who had been appointed by the Bourbon monarch, began his inspection tour of the South American postal system. After completing his journey, however, his recommendations for change were rejected by the bureaucracy. Disillusioned by this response, Carrio wrote a literary account of the episode, which is a general critique of Spanish American society' and an excellent example of Menippean satire produced in the New World.

In order to protect himself from retaliation, Carrio presented the work as an account written by his Indian guide, Concolorcorvo, and gave a false date and place of publication for the book. The work, which was probably unlicensed, was printed in Lima in 1775 or 1776 and not in Spain as stated on the title page. The publishing house “La Rovada” translates as “Something Stolen.”

Mercurio peruano de historia, literatura, y noticias públicas que da à...

1791-1795

-

p. 7

p. 7The circulation of news in printed form probably began in South America in 1594. At that time Antonio Ricardo published a fifteen-page pamphlet on the English pirate Richard Hawkins, who had been sent by Sir Francis Drake to disrupt Spanish trade and commerce along the South American coast. News was distributed on a regular basis throughout most of the seventeenth century, and in 1744 the first Peruvian newspaper, La Gaceta de Lima, was established. It was followed by the Mercurio Peruano, an exceptional periodical published by the “Sociedad Económica de Amantes del País". Influenced by the Enlightenment, members of this organization expressed an interest in everything from literary trends to political change, and they stood at the forefront of Peru’s intellectual life.

Although the Mercurio Peruano disseminated much information, such as the results of a 1790 census of Lima, government pressure forced it to cease publication after only five years.

The Captaincy-General of Chile

El monitor araucano

1813-1814

-

p. 1

p. 1By the middle of the eighteenth century, through the efforts of the German Jesuit Carlos Haimhausen, the printing press had arrived in Chile. The expulsion of the Society of Jesus from Spanish domains in 1767, however, disrupted its operation and made the role of printing in Chilean life uncertain for many years.

The growth of the Chilean nationalist movement, however, increased the need for printed pamphlets and broadsides, and the equipment and artisans sent from the United States helped to re-establish printing. In 1812 the Aurora de Chile, the region's first newspaper, was founded, and the next year it was followed by El Monitor Araucano.

Both periodicals were used to circulate news about the latest developments in the campaign for independence and to increase patriotic fervor among Chile’s residents.

Proclama a los habitantes del estado de Chile. Compatriotas: al fin se a...

1820

-

p. 3

p. 3In 1817 the liberator José de San Martín crossed the Andes into Chile, a journey that took men, livestock, and military machinery through mountain passes more than two miles above sea level. After winning battles at Chacabuco and Maipú, San Martín made lengthy preparations for the next and most crucial phase of his campaign, the march northward and the assault on royalist troops in Peru. This 1820 broadside, issued four years before the last battle for independence from Spain, is an open declaration of rebellion and calls on all Americans to preserve civil order while the armies readied themselves for the coming campaign against the royalists.

The Intendency of Paraguay

Señor. Antonio Ruiz de Montoya de la Compañia de Iesus, y su procurado...

1639-1640

-

p. 1

p. 1In 1537, after the outpost at Buenos Aires was destroyed by the Indians, the Spaniards made their way a thousand miles up the Paraguay River to build the area’s first permanent settlement at Asunción. Half a century later, Jesuit missionaries began to enter Paraguay, which then included modern-day Uruguay, northern Argentina, and southern Brazil. The story of their successful establishment of reducciones or communal villages among the Guarani Indians is the most dramatic in the history of Christian evangelism in the New World. The protection of their new converts, however, became a major concern for the Jesuits as Brazilian slave hunters from São Paulo continued to raid their settlements. In Señor, a letter of protest to the King of Spain, Father Antonio Ruiz de Montoya accused one Antonio Raposo de Tavares of having led a force from Buenos Aires in an attack on a Jesuit mission in Paraguay. This is the only recorded copy of the work in the United States.

Catecismo de la lengua guarani

1640

-

p. 7

p. 7Father Antonio Ruiz de Montoya was not only a leader of the Jesuit reducciones, he was also a specialist in Guarani linguistics. The catechism and grammar, two of his early works, are among the first books ever printed in that South American language.

Because there was no printing press in Paraguay, the Jesuits sent their manuscripts to Spain, but they expressed concern over the ability of Spanish printers to set type accurately using the Guarani alphabet that they had devised.

Arte, y bocobulario de la lengua guarani

1640

-

p. 9

p. 9The acquisition of language skills played an important role in the organization and progress of the missions, forging a model for the development of Indian culture. Although the law stipulated that American natives were to be taught Spanish, it was not enforced at the time the Jesuits began establishing their missions in Paraguay. Thus they trained their Indian charges to read and write in their own language and standardized its usage through instruction. Critics of the Jesuits charged that they were creating an autonomous state within the Spanish American colonies whose citizens were being taught to resist Hispanization.

Vocabulario de la lengua guarani

1722

-

p. 5

p. 5Although the Jesuits asked the crown for permission to establish a press soon after their arrival in Paraguay, years passed before it became a reality.

Libraries did exist, however, and contained books sent from Spain, copies of works made by Indian scribes, and short pieces allegedly produced locally on a block press. Father Juan Baptista Neumann (1659-1705) built the earliest letterpress used in Paraguay and created the type needed for its operation. Native materials and labor were utilized as much as possible in all phases of the printing process, and only paper was imported from Spain.

Among the titles printed between 1700 and 1727 were works by Father Montoya that had originally been published in Spain.

Arte de la lengua guarani

1724

-

p. 7

p. 7Appearing some seventy years after Father Montoya’s death, these extremely rare books were excerpted from the Arte y bocobulario (1640).

Instruccion practica para ordenar santamente la vidà; que ofrece el P. ...

1713

-

p. 7

p. 7The first printing press in Paraguay was probably established in Loreto. It is unclear, however, whether it moved from place to place or whether other presses were actually built in the missionary stations of Santa Maria la Mayor, San Francisco Xavier, and possibly Candelaria. Remnants of an early press, which are housed today in the Museum of the Cabildo in Buenos Aires, were recovered from this general area and allegedly belonged to the Jesuit printing network.

Instruction practica, a product of the Loreto press, is a guidebook for priests written by the Mallorcan Father, Antonio Garriga, who composed it in Chuquisaca on his trip from Lima to Cordoba. This is the only recorded copy of this book in the United States.

Sermones y exemplos en lengua guarani

1727

-

p. 5

p. 5This collection of Guarani sermons, written by Nicolas Yapuguay, was one of the last works to be printed in the Jesuits’ communal villages. By the middle of the eighteenth century, there were about thirty missions in existence with approximately 100,000 Indians under their jurisdiction. The system flourished until 1767, when members of the Society of Jesus were expelled from Spanish America.

Although the Indians may be said to have benefited from the Jesuits’ paternalistic rule, they had not been taught how to manage the communities on their own. Despite the arrival of able replacements from other religious orders to supervise the Paraguayan missions, they soon disintegrated.

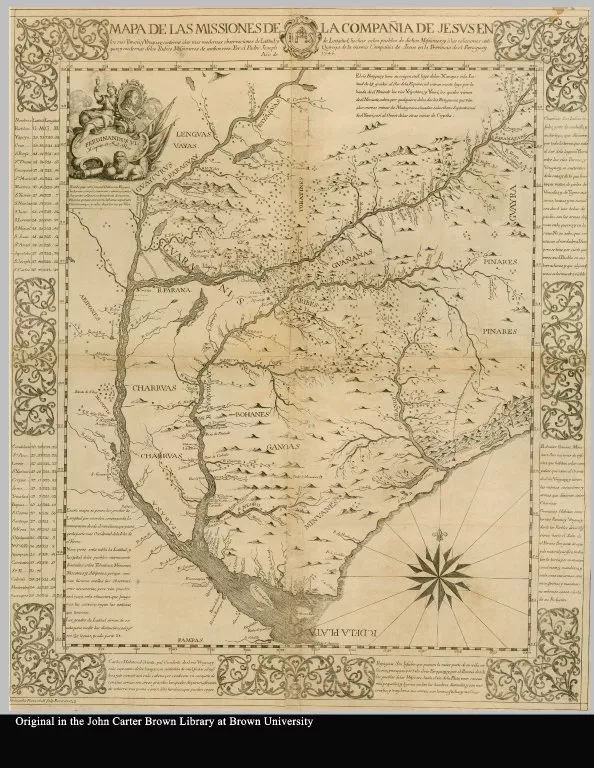

Mapa de las Missiones de la Compañia de Jesvs en los rios Paranà y Vrugu...

1753

-

p. 1

p. 1In 1753 José Quiroga (1707-1784), a member of the Society of Jesus in Paraguay, prepared a map of the Jesuit missions. The map, measuring 38" by 31 ¾", was engraved by Ferdinand Franceschelli and published in Rome.

The Intendency of Buenos Aires

Carta circular, ò edicto, de el ilustrisimo, y reverendisimo señor D. ...

1781

-

p. 9

p. 9In 1764 the German Jesuit, Pablo Karrer, established a European printing press in Córdoba. When the Society of Jesus was expelled from the colonies three years later, however, all publication ceased, and the equipment from the print shop was confiscated. The Franciscans took over the university where the press was housed and, on the orders of the Viceroy Juan José de Vértiz y Salcedo, sent it to Buenos Aires in 1780. There it became known as the “Imprenta de los Niños Expósitos."

The Carta circular, issued by the Bishop of Córdoba del Tucuman, concerns advancement in religious orders. It was printed during the press’s second year of operation.

The North American Borderlands

La relacion que dio Aluar Nuñez Cabeça de Vaca de lo acaescido en las ...

1542

-

p. 3

p. 3Although no colonial presses were established in the Spanish territories that are now part of the southern United States, the region was of considerable interest to explorers, writers, scholars, and members of religious communities. The earliest account of a trip through this area was written by Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, who was treasurer of the ill-fated expedition sent to Florida in 1527.

This unfortunate group of men was shipwrecked at the present site of Matagorda Bay, Texas, and Cabeza de Vaca and three other survivors spent nine years wandering in the wilderness before making their way to Sinaloa. His journal provides valuable ethnographic information about numerous native American tribes—and the profile of a Spaniard who found himself constantly at the mercy of the Indians.

Relaçam verdadeira dos trabalhos q[ue] ho gouernador do[m] Ferna[n]do d...

1557

-

p. 9

p. 9This account by an anonymous Portuguese volunteer who accompanied Hernando de Soto on his expedition through the present southeastern United States contains the first description of the exploration of the Mississippi River and its delta. As a military mission, the expedition was deemed a failure because it did not uncover any wealthy civilizations and because De Soto died before its completion.

The information gathered by the “Gentleman” from 1539 to 1543, however, enabled cartographers to determine correctly the shape of the land mass from Florida to the Mississippi River. This, together with facts provided by Cabeza de Vaca, led to the creation of maps of the entire southern part of the present United States drawn with considerable accuracy. Only two copies of this book are reported in the United States.

La Florida del Ynca

1605

-

p. 5

p. 5Several other participants in De Soto’s expedition returned to Spain at its conclusion, and there they met the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, who had left his native Peru and was living near Córdoba. Making use of their detailed testimony, the Inca imaginatively reconstructed the important events of their daring march to the Mississippi. Such an account, he hoped, would stimulate interest in the area and encourage the Spanish to conquer and colonize it.

Description, que de la vaia de Santa Maria de Galve (antes Pansacola) de...

1720

-

p. 1

p. 1Although the Spaniards tried to establish settlements from Tampico to Apalache, their efforts failed, and the region fell into general neglect. This was changed, however, by ambitious Frenchmen, who sought to found a colony along the shores of the Gulf of Mexico during the latter part of the seventeenth century. Because of the intrusion of La Salle’s expedition, the Spanish government moved to protect the borderlands by setting up missions in Texas and by occupying Pensacola Bay.

Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Gongora took part in one of the investigative voyages to the Bay at the request of New Spain’s Viceroy, the Count of Galve. Returning to Mexico City in 1693, he wrote this report on his reconnaissance in which he outlined plans for Pensacola's settlement and the defense of its coastline. This is the only recorded copy of this thirty-two-page pamphlet in the United States.

Relacion historica de la fundacion de este Convento de Nuestra Señora d...

1793

-

p. 20

p. 20Women as well as men were called to settle the Spanish borderlands. The biography of the nun Maria Ignacia Azlor y Echeverz (1715-1767) recounts how she founded a convent dedicated to the education of young girls. Maria Ignacia Azlor y Echeverz was the daughter of the Marquis of Aguayo, governor of Coahuila and Texas and one of the first settlers of the area.

When she entered the convent, she brought with her the considerable fortune her family had made from the Mazapil silver mines.

In the eighteenth century, the road from the Franciscan mission at San Antonio to Sister Maria Ignacia’s Convent of Nuestra Senora del Pilar was more than seven hundred miles long. Among the missions depicted on the 1764 map of the area is that of San Antonio de Valero. It later became known as the Alamo, and was the site of the 1836 massacre led by the Mexican General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna.

The Viceroyalty of New Granada

Arte de construccion

1784

-

p. 5

p. 5By the eighteenth century, Spain’s empire had become too cumbersome to be ruled from Mexico City and Lima, and the Bourbon kings created new territorial and administrative divisions, including the Viceroyalty of New Granada (1717). By then, printing presses were in operation in many parts of the Spanish American colonies, not just in the old viceregal centers of political or religious activity.

The Jesuits brought the first press to Bogota, the major city of New Granada, but their expulsion in 1767 interrupted its operations. In 1777 Antonio de los Monteros, who had established a print shop in Cartagena some years earlier, relocated in Bogota and took over some of the equipment left by the Society of Jesus. His press printed Masustegui’s Arte de construccion, an instructional manual on the methods of Latin translation that had been published in Seville in 1734.

The Captaincy-General of Cuba

Descripcion de diferentes piezas de historia natural las mas del ramo maritimo

1787

-

p. 13

p. 13Immediately following the discovery of America, the island colonies of the Caribbean were the center of activity, but they were neglected soon after the conquest of Mexico and Peru. Even Cuba, the most important and the wealthiest, probably did not have a fully operational press before the eighteenth century. Among the printers who practiced their trade in Havana was Esteban José Boloña, whose works are noted for their exceptional quality.

The plates he prepared for the Descripción de diferentes piezas de historia natural, one of the first books produced on his press, are good examples of his talent for design, and the recognition he received subsequently won him an appointment as printer for the Royal Navy.

The Captaincy-General of Venezuela

The Book and Printing in Portuguese America

Brazil

Auisi particolari delle Indie di Portugallo riceuuti in questi doi anni ...

1552

-

p. 1

p. 1In 1549, João III took decisive measures to establish Portuguese control over Brazil by sending a group of settlers to the colony under the leadership of Captain-General Tomé de Souza. Among its members were Father Manoel da Nóbrega and five companions, the first Jesuits to arrive in America after the Society’s founding in 1540. Under orders from Ignatius Loyola himself, missionaries throughout the world were to report on the progress of their work and to take note of unusual plants and animals that flourished in their exotic surroundings. Because of the general interest in the letters sent to Loyola, they were edited and published in Rome. In 1552 the first report appeared with news of the Brazilian mission.

This is the only copy of this work recorded in the United States.

Os Lusiadas de Luis de Camões

1572

-

p. 5

p. 5Much information regarding the composition and size of libraries in colonial Brazil has been gathered from legal documents that enumerate items of seized or taxed property. A frequent work listed in these inventories is that of the epic poet Luis de Camões, Portuguese literature’s most prominent figure. After attending the University of Coimbra, he began a tumultuous period in his life that took him all over the world and brought him into constant conflict with ecclesiastical and government authorities. In 1553, he was released from prison and required to leave Portugal for the Orient.

His travels to India took him over the sea route followed by the navigator Vasco da Gama, the first European to arrive there by ship. This momentous journey, from which the Portuguese empire would emerge, became the central theme of Camões' epic. His interpretation of the event was much influenced by the works of Virgil and Ariosto. In 1570 he returned to Portugal where his verses were published two years later. Os Lusiadas won immediate acclaim and is considered one of the greatest epic poems of world literature. At the end of Canto X, Vasco da Gama is described as he contemplates the Portuguese development of South America and predicts that the colony will be named Brazil because of the red brazilwood growing there.

Noticias do que he o achaque do bicho

1707

-

p. 3

p. 3The threat posed by the Brazilian environment to the health of colonists was a matter of great concern and prompted the publication of a number of works on tropical medicine. In 1685 there was an outbreak of yellow fever in Pernambuco, which spread to Rio de Janeiro the following year. The account of the epidemic, by a Brazilian physician, was the first based on clinical observations to be written in the Portuguese colony. This copy of the work is unique in the United States.

Catecismo brasilico da doutrina christãa

1686

-

p. 9

p. 9The arrival of the Jesuits marked the beginning of organized Christianity in Brazil, and the Society’s progress was the most dynamic of any religious order until its expulsion from Portugal and its South American colony in 1759. In contrast to the Jesuits in other parts of the world, however, the missionaries to Brazil did not have access to a press and consequently depended on printers in Lisbon to supply them with religious works such as this extremely rare catechism.

The Jesuits were the principal agents for the transfer of European culture to the Indians. They established mission villages (reduções), where they founded many of their schools and libraries. The Jesuits’ effectiveness in protecting the Indians from slavery brought them into conflict with powerful fazendeiros, who supported the Society’s banishment. Lists of Jesuit property seized at the time of their expulsion attest to the excellence of their libraries. The largest was that of Rio de Janeiro's Jesuit College.

Marilia de Dirceo

1792

-

p. 9

p. 9The metropolis of Vila Rica (the former capital of Minas Gerais province and now the city of Ouro Preto) was a center for the arts by the middle of the eighteenth century. It became a gathering place for members of Brazil’s intelligentsia who were primarily responsible for the colony’s cultural achievements. During the latter part of the eighteenth century, they became the leaders of the Inconfidencia mineira, a movement advocating independence from Portugal.

Among the prominent poets residing in Vila Rica was Tomás Antônio Gonzaga, who was born in Portugal of Brazilian parents. The tragic story of his love for Maria Dorotéia is told in his Marilia de Dirceo, and it achieved an immediate success unprecedented in the early literary history of the colony. There was no press in Brazil when the work was completed, so the manuscript was sent to Portugal for publication.

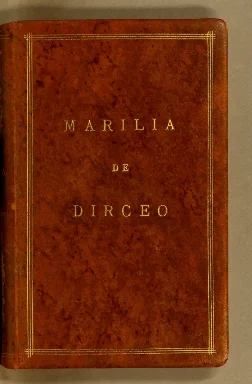

Marilia de Dirceo

1810

-

p. 7

p. 7Because sales were so brisk, four editions were printed in Lisbon between 1792 and 1800, and it would also be the first literary work printed by the Impressão Régia in Brazil.

Relaçaõ da entrada que fez o excellentissimo, e reverendissimo senhor ...

1247-1747

-

p. 3

p. 3Although several historians suggest that a printing press was in operation in Recife, initially under the direction of the Dutch and later during the administration of the Portuguese governor Francisco de Castro Moraes, the first press for which definite proof exists is that of Antonio Isidoro da Fonseca in Rio de Janeiro. He had established a fine reputation as a printer in Lisbon before coming to Brazil and is noted for his publication of Barbosa Machado’s Biblioteca lusitana, a pioneering reference work in Portuguese bibliography. His reasons for coming to the New World are unclear; it is known, however, that he was in some economic difficulties and that the Inquisition was also investigating several of his publications.

Fonseca produced very few works on his press in Rio, for he was ordered by royal officials to close his shop in 1747, the same year that he began printing. Cunha’s Relação is believed to be the first book printed in Brazil, and only six copies of it are known to exist at the present time. It was not, however, the first book to be printed in Portuguese in the New World. A priest in New Spain, Father João Bauptista Morelli de Castelnovo, wrote Dom. Luzeiro Evangelico to support the Church's evangelizing efforts in Asia, and it was published in Mexico in 1710.

O Uraguay

1769

-

p. 9

p. 9Brazil’s first epic poet, José Basílio da Gama, was born in Minas Gerais and educated at the Jesuit College in Rio de Janeiro. Although he considered becoming a member of the Society of Jesus during his youth, before the Society’s expulsion, he was to change his stance as anti-Jesuit sentiment became politically essential. Portugal’s Prime Minister, the Marquis of Pombal, led the campaign against the Jesuits, and the poet endeavored to win his favor by advocating his policies.

Gama’s five-canto poem contains an account of the campaign to put down an Indian revolt allegedly inspired by the Jesuits. The uprising took place in the buffer state of Sacramento, present-day Uruguay. O Uraguay is recognized as one of the outstanding works of early Brazilian literature, and it anticipates the emergence of certain Romantic themes, such as the “noble savage” and the cult of nature. Gama’s work was one of the first to be published by Portugal’s government press or Impressão Régia, which Pombal had established the previous year.

Codigo Brasiliense

1811-1822

-

p. 1

p. 1The period of exile for the Portuguese crown and government in Brazil brought many changes to the colony, among them the installation of a printing press which quickly became an indispensable tool of administration. In 1808, the authorization for printing was officially granted, and the Impressão Régia was established in Rio.

The origin of the equipment used to set up this government print shop has not been firmly established. One account claims that the new presses and type had arrived from England just prior to the French invasion and were still on the docks in Lisbon at the time of the court’s evacuation. As the last ships were leaving the harbor, the foreign secretary, Antonio de Araújo Azevedo, had them loaded onto a frigate for shipment to Brazil.

The one-page decree establishing the government press appeared in Volume 1 of the Codigo Brasiliense, a collection of laws.

Elementos de astronomia par uso dos alumnos da Academia Real Militar

1814

-

p. 5

p. 5The Impressão Régia enjoyed a monopoly over printing in Rio for fourteen years. During that time more than twelve hundred items were produced, and the press’s activity increased considerably in 1821 when censorship was abolished in Brazil. Although most of the products of the press consisted of official documents, religious works, and broadsides, books used for instruction in the city’s schools were also printed.

Among them was Araújo Guimarães’s basic text on astronomy, which he prepared for the students of the Royal Military Academy. This is the only copy of the work recorded in the United States

Notes on Rio de Janeiro, and the southern parts of Brazil; taken during ...

1820

-

p. 7

p. 7The Impressão Régia enjoyed a monopoly over printing in Rio for fourteen years. During that time more than twelve hundred items were produced, and the press’s activity increased considerably in 1821 when censorship was abolished in Brazil. Although most of the products of the press consisted of official documents, religious works, and broadsides, books used for instruction in the city’s schools were also printed.

Among them was Araújo Guimarães’s basic text on astronomy, which he prepared for the students of the Royal Military Academy. This is the only copy of the work recorded in the United States

Credits

Items Pending Integration

Original Catalogue

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library