During the migration of our legacy catalogs and past exhibitions into Americana, there are occasionally items that cannot be immediately included in our new environment. This may happen for two reasons: the item in question is not yet cataloged, or it was lent by another institution.

Any items that are not integrated into Americana are included in this section and added to our processing queue.

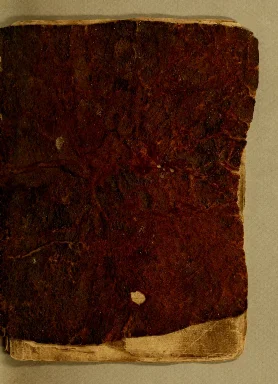

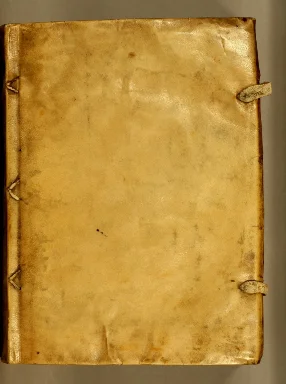

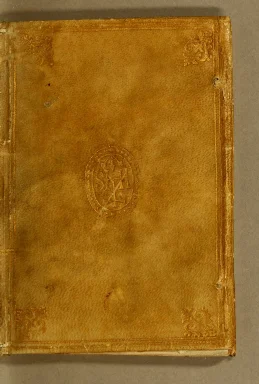

Gabriel Biel (d. 1495). Repertorium generate & succinctum: vern[m) tame

\ valde utile atq[ue\ necessariu\m ]: contentoru[m\ in quatuor collectoriis , acutissimi ac profundissimi theologi Gabrielis Biel super quatuor libros sententiarum. Lyon, 1527.

LENT BY THE SUTRO LIBRARY, SAN FRANCISCO.

This treatise on the Gospels belonged to Fray Juan de Zumárraga’s personal library, which contained more than four hundred volumes at the time of his death in 1548. The tide page (fig. 2) bears his signature.

Miguel de Medina (1489-1578). De sacrorum hominum continentia libri v. Venice, 1569.

LENT BY THE SUTRO LIBRARY, SAN FRANCISCO.

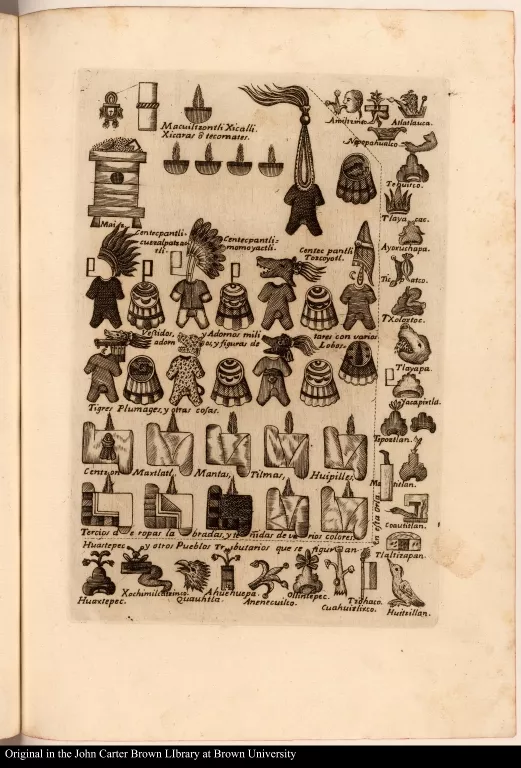

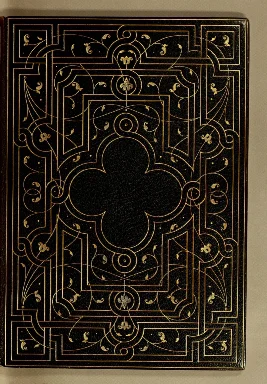

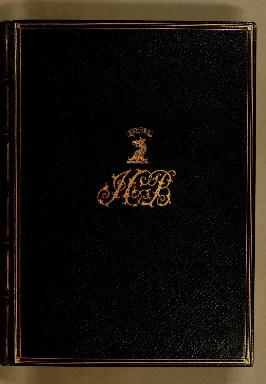

As an important educational center in New Spain, the Colegio Imperial de Santa Cruz at Santiago Tlatelolco attracted numerous scholars, who consulted the many volumes of its extensive library. This theological work (fig. 3), once in the Colegio’s library, bears the signature of the Franciscan missionary Fray Juan Baptista and was designated for his use only {ad usurri). Because he was a member of a mendicant order, he was not permitted to own any personal property.

Fray Juan Baptista, who was born in New Spain, entered the Franciscan Order at the great convent of Mexico and taught philosophy there. He spent his later years at Tlate¬lolco, where he served as guardian and be¬ came one of the leading authorities on the Nahuad language.

Between 1599 and 1601, his well-known Confessionario en lengua mexicanay castellana and several other bilin¬ gual works were printed at the Colegio by Melchor Ocharte.

In 1536, the book was presented to the first European academic library in the Americas, established in the Colegio Imperial de Santa Cruz at Santiago Tlatelolco. During his stay in Spain (1532-1534), Zumarraga’s petitions to the crown led to the foundation of the Colegio, one of the earliest institutions of learning in the New World.

New Spain. Ordena[n]ças y copilacion de leyes: hechas por el muy illustre senor don Antonio d[e] Me[n]doça Visorey y Govemador desta Nueva Espana: y Preside[n]te de la Audie[n]cia Real q[ue] en ella reside: y por los Senores Oydores d[e] la dicha audie[n\]cia:p[ar]a la bue[n]a governacio[n] y estilo d[e] los oficiales della. Mexico, 1548.

LENT BY THE SUTRO LIBRARY, SAN FRANCISCO.

In addition to producing religious materials, Juan Pablos also published a number of secular works. Among them was the Ordenanças, the first law book printed in the New World. It was compiled by the first Viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, who served in that post from 1535 to 1550. In the latter year he was appointed Viceroy of Peru, where he served until his death in 1552.

This sixteenth title issued by the first American press is an extraordinary example of early Gothic-letter typography (fig. 6). Only two copies are known to exist: this one from the Sutro Library which was originally a part of the library at the Franciscan monastery of Texcoco, and the one in the Lenox Collection of the New York Public Library. The laws included in the Ordenanças were later incorporated into the better-known Pbilippys Hispaniarum et Indiarum Rex, compiled by Doctor Vasco de Puga (who served as a judge on the Audiencia of Mexico) and printed in 1563 by Pedro Ocharte, Mexico’s third printer.

Sister Juana Ines de la Cruz (1648-1695). Villancicos. Mexico, [1677].

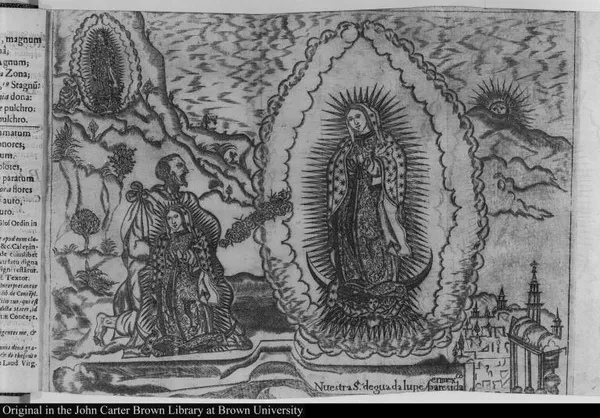

Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, whose brilliant literary career as a poet, prose writer, and playwright won her the title of the “Tenth Muse,” composed numerous poems for religious festivities in Mexico. Among them are her villancicos, or church carols sung on Catholic feast or saints’ days. Although the musical notations for these pieces were not recorded, the lyrics were printed especially for the occasion. When they published villancicos, printers usually followed the small quarto format and placed a woodcut of the Virgin or the saint being honored on the title page (fig. 31). This particular song, written in praise of Saint Peter, is a blend of elements of Mexican culture with aspects of Catholic ritual. In the “Enzalada,” one of the composition’s intercalated poems, a mestizo comes forth to express his sentiments toward this holy man (fig. 32).

No other copy of the villancico to Saint Peter is known to be in the United States

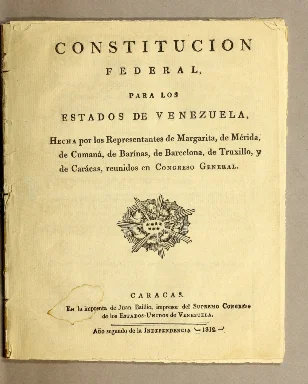

Mexico. Decreto constitucionalpara la libertad de la America mexicana: sancionado en Apatzingan a 22 de octubre de 1814. Apatzingan, [1814].

LENT BY THE SUTRO LIBRARY, SAN FRANCISCO.

Although the movement for independence in New Spain was begun by Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla at Dolores in 1810, a concrete plan for an independent state was not formulated until 1813. At that time, the Acta de Independencia was drawn up and signed at Chilpancingo. A constitutional congress then drafted an organic law for the creation of a new nation. The twenty-two articles of the Decreto constitucional established a Catholic, egalitarian, and sovereign state free to elect the form of government most suited to its citizens. Military pressure by royalist troops forced the constitutional congress and its press to move from place to place throughout the modern states of southern Michoacan and northern Guerrero. Finally, at Apatzingan on October 22, 1814, the Constitution was signed by Jose Maria Liceaga, Jose Maria Morelos, Jose Maria Cos, and Remigio de Yarza.

The printed copy of the Constitution from the Sutro Library, dated October 24, 1814, includes the rubricas (individual flourishes similar to initials) of the four signers (fig. 45). It is the only copy reported to be held by a collection outside of Mexico.