1. First Presses

[Manual de adultos]

1540

-

p. 5

p. 5Early Mexico

This facsimile, taken from the only known copy at the National Library of Spain, is the earliest extant remnant of the press in Mexico. It consists of one page of Latin verses by Cristóbal de Cabrera, followed by errata.

Pragmatica sobre los diez dias del año

1584

-

p. 7

p. 7The First From Peru

Originally from Turin, Antonio Ricardo arrived in Mexico as early as 1570, and began as a printer there in 1577. Summoned to Peru by the Jesuits to print texts emerging from the Third Council of Lima, the royal license to open the press was long delayed. Nevertheless, printing of the Doctrina christiana (1584) began even before the King's license arrived. It was interrupted, however, by notice of the calendrical reforms ordered by Pope Gregory XVIII. This pamphlet, thus, is the earliest surviving item off the press in Peru.

Arte y reglas de la lengua tagala

1610

-

p. 1

p. 1Early Manila Imprint

Xylographic (woodblock) printing was executed in China as early as the ninth century CE, and spread throughout South East Asia. The earliest books printed in the Philippines following the arrival of the Spanish, a Doctrina christiana and the Shih-lu, both in 1593, were likewise printed using xylography. With the arrival of a press and types in 1602, printing in the European fashion began. As with Mexico and Peru, many of the earliest works were doctrinal texts in indigenous languages, or studies of the languages themselves. This book has not been digitized due to its fragile state.

Confessionario muy copioso en dos lenguas, aymara, y española

1612

-

p. 7

p. 7A Press in Juli?

There remains some debate about the four books, all from 1612, bearing the imprint of Francisco del Canto in the Jesuit province of Juli. Del Canto was in jail for debts for much of 1612, thus it appears unlikely that he had an active role in printing these texts. Were they actually printed in Juli, with the Jesuits simply using del Canto's name as cover? Or instead, were they printed at del Canto's press in Lima with Juli simply referring to place of issuance?

Historia real sagrada, luz de principes. Y subditos

1643

-

p. 1

p. 1A Fitful Start in Puebla de los Angeles

Printing had a fitful start in Puebla de los Angeles, with no fewer than five printers at work there between 1642 and 1651. Pedro Quiñones printed the first surviving work, the Sumario of 1642. He and two other printers produced no more than one identifiable volume each, and a forth only two. The remaining printer, Juan Blanco de Alcázar printed a number of volumes between 1646 and 1651, but was ultimately silenced by the viceroy. It was not until the Borja family of printers began in 1654 that the press was well established.

El maestro D.F. Payo de Ribera, obispo de Goatemala, y de la Verapaz, re...

1664

-

p. 5

p. 5Guatemala la Antigua

José de Pineda Ibarra, the first printer in Guatemala, was born in Mexico and worked there for both Paula de Benavides, the widow of Bernardo Calderón, and Hipólito de Ribera, the two most prominent printers of the time. Guatemala's newly appointed Bishop Payo Enríquez de Ribera charged Francisco de Borja with finding a press and printer and sending them to Guatemala. Borja found Pineda Ibarra in Puebla de los Angeles, but it is not entirely clear where his press came from. Juan Blanco de Alcázar's press went to the Colegio de San Luis following his death, and only one book from 1657 is known with their imprint, thus this appears to be one possible source.

Instruccion practica para ordenar santamente la vidà; que ofrece el P. ...

1713

-

p. 7

p. 7The Mission Press in Paraguay

Requests by the Jesuits for a press in their Paraguayan missions began as early as 1633, but it would not be until 1700 that these requests were granted. Until that time, books were imported, or produced in manuscript and some of the latter still survive. In 1700, the first printed book appeared, Juan Bautista Neumann's Martirologio Romano, since lost. The first extant book printed in the missions is Juan Eusebio Nieremberg's De la diferencia entre lo temporal y eterno. All the paper for these books had to be imported from Spain, but the press was constructed in the missions, and the type was cut and cast there as well. As many as 23 books were printed in the missions between 1700 and 1727, although only nine titles survive today. For reasons that have yet to be fully explained, printing ceased in 1727, 40 years prior to the expulsion of the Jesuits.

Affectuosa novena de la santissima Virgen Maria, en su milagrosa advocac...

1739

-

p. 5

p. 5The Jesuit Press in New Grenada (Colombia)

While there have been some suggestions of small scale job printing taking place in New Grenada as early as the late seventeenth century, the first book appeared only in 1738, at the Jesuit press administered by Francisco de la Peña. The vast majority of early Bogota imprints were novenas in quarto format. These small devotional texts gained great popularity in the early eighteenth century.

Relaçaõ da entrada que fez o excellentissimo, e reverendissimo senhor ...

1247-1747

-

p. 3

p. 3Early Brazilian Printing

Unlike Spanish America, and indeed, unlike their possessions in Goa, Macau and elsewhere, the Portuguese did not establish a press in Brazil. A printer, Pieter Janszoon, and press were sent to Dutch Pernambuco in 1643, however Janszoon died immediately on arrival and no other printer could be found. As with New Grenada, there have been some suggestions of small scale job printing in Recife as early as the first decade of the eighteenth century, but no solid evidence has been found to confirm the conjecture. Lisbon printer Antonio Isidoro da Fonseca became the first known printer in Brazil, publishing this pamphlet in February of 1747. One other work is known from his press--an announcement of a thesis defense on silk--and two others are suspected. By May of that year, however, royal orders were sent to silence the press and have Fonseca returned to Lisbon.

Relação dos despachos publicados na Corte pelo expediente da Secretari...

1808

-

p. 3

p. 3The Impressão Regia

When Prince João left Portugal for Brazil on November 29th, 1807, he took with him hundreds of members of the court and their families. He also took with him some 60,000 volumes of the national library, and, as luck would have it, two presses and twenty-eight cases of type that had been ordered from England some months previously but were still at the docks. This pamphlet is the first item off that press, printed on the Prince Regent's birthday.

Reglamento que de orden de S. M. ha hecho el excelentissimo señor Conde...

1764

-

p. 3

p. 3The Press in Havana

Although there are notices of books printed in Havana as early as 1707, they are assuredly bibliographical ghosts. The first book printed in Havana was long thought to be the Tarifa general de precios de medicinas (1723), by Carlos Habré from Ghent. Recently, a 1722 imprint was identified, a novena for Saint Agustin. Nevertheless, Habré printed very little, and likely with a binding press rather than a true printing press. He was followed by Francisco José de Paula, who likewise printed little. The industry only began to flourish with the appearance of Blas de los Olivos around 1756.

Carta pastoral

1781

-

p. 7

p. 7Rio de la Plata and the Press of the Niños Expósitos

A press began operations in 1766 in Córdoba del Tucuman, Argentina, at the Jesuit colegio of Montserrat. It ceased the following year, owing to the expulsion of the Company from Spanish realms. The press was seized, and remained there, inoperative, until 1779 and the opening of the orphanage, or, Casa de niños expositos. Viceroy Juan José de Vértiz y Salcedo requested the press for the Casa, in order to help pay for its expenses, and it began operations there the following year.

Aurora de Chile

1812-1813

-

p. 5

p. 5New York Printers in Chile

The first printing press to arrive in Santiago was also brought by a Jesuit, one Carlos Haimhausen in 1747. It was installed at the Universidad de San Felipe, but there is no clear evidence that it was ever put into operation prior to the expulsion of 1767. While some printing took place in Santiago de Chile as early as 1780, with few exceptions, until 1811 it was typically confined to forms such as the above. In that year, Mateo Arnaldo Hoevel arranged with John R. Livingston of New York to bring a press and three printers--Samuel Burr Johnston, William H. Burbidge, and Simon Garrison--to Santiago. They produced the Aurora de Chile, that ran from 13 February 1812 to 1 April 1813.

Boletin del Egercito Nacional de Lima

1822

-

p. 3

p. 3Portable Presses

With the Constitution of Cádiz at least nominally allowing freedom of the press, other cities began to acquire printing presses in quick succession. During the wars of independence, there were likewise portable presses that accompanied the armies to announce battlefield victories, as here, from "The press that belonged to the enemy division from the South."

2. Printing House and Printing Press

Vocabulario manual de las lenguas castellana, y mexicana

1611

-

p. 7

p. 7Press Building

In 1599, Cornelio Adrian César began building a press in Mexico City, for which Enrico Martínez was cutting and casting type. César fell afoul of the Inquisition, accused of heresy, and his press was seized and put on deposit with Martínez. The latter began printing in that year, and César was sentenced to work at the press of Diego López Dávalos in Tlatelolco, just outside of Mexico City.

Sermon al glorioso San Francisco de Borja, duque quarto de Gandia

1688

-

p. 1

p. 1Presses From the Low Countries

With the exception of César's press, and that of the Jesuits in Paraguay, we have no notice of press-building in Latin America during the viceregal period, and ample evidence of their importation. Most were brought from Antwerp, frequently from the Plantin firm, one of the Continent's largest printing houses. In 1657, Antonio Calderón ordered a press and type from Antwerp, and presses from Mexico, Puebla, and Lima frequently sported Antuerpiana, or Plantiniana in their imprint lines.

Carta pastoral que el illmô. señor doctor D. Alonso Nuñez de Haro y P...

1777

-

p. 5

p. 5Other Imported Presses

While Antwerp was the preferred source for presses (and type), at least one press came from Paris, operated by the Colegio de San Ignacio in Puebla (1758-1768). With the revival of typographic arts in Spain in the third quarter of the eighteenth century, printers began ordering their presses from Madrid.

Parentacion real al soberano nombre e immortal memoria del Catolico Rey ...

1701

-

p. 314

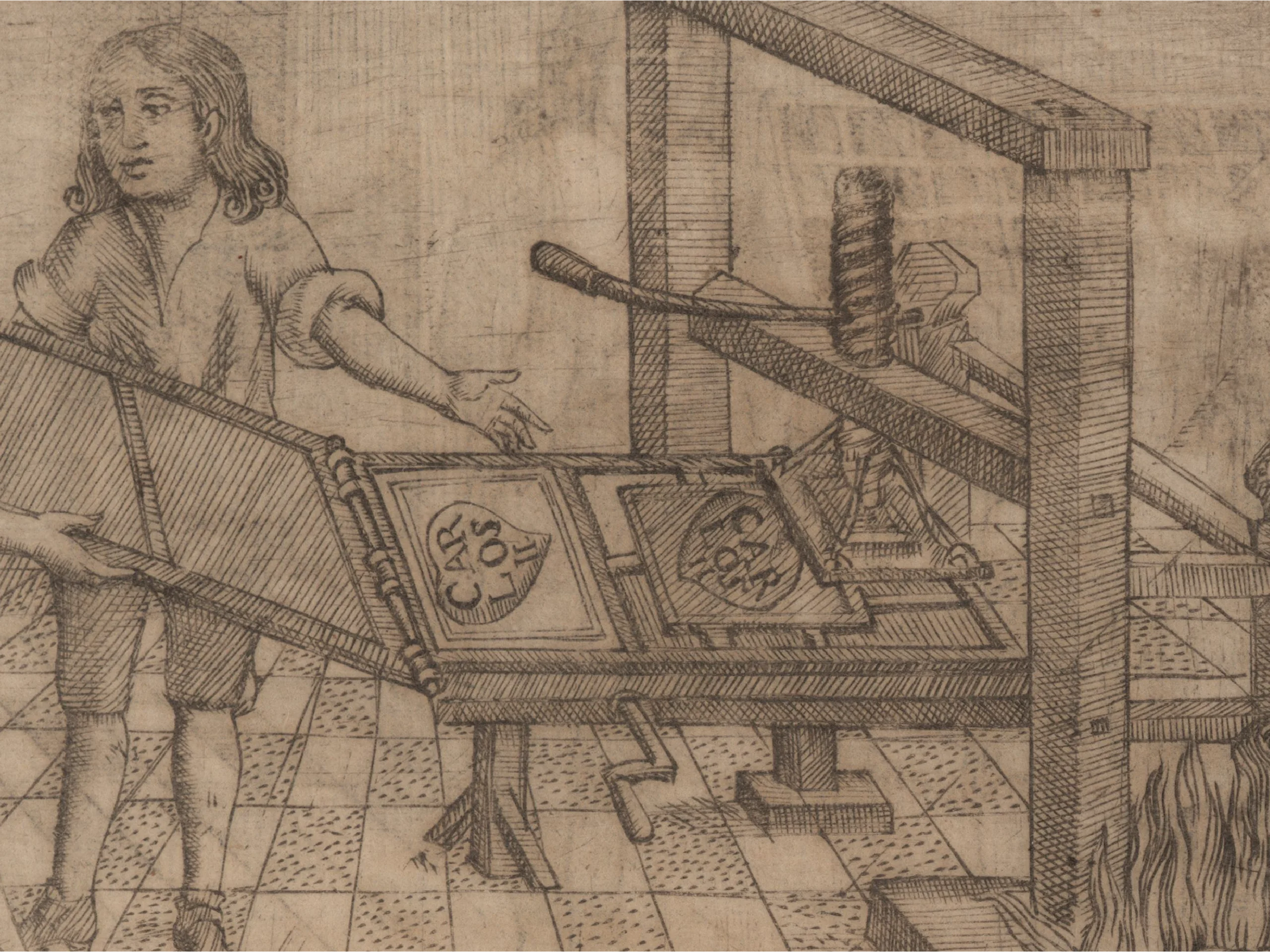

p. 314This engraving of José de Contreras of Lima is the only image we have of a printer working his press during the viceregal period.

3. Type, Ink and Paper

Este es vn co[m]pe[n]dio breue que tracta d[e]la manera de como se ha[n]...

1544

-

p. 5

p. 5Early Typography

Spanish printers were very conservative in their typography, retaining the use of gothic type long after Roman had been adopted elsewhere. Thus, of course, the Mexican branch of the Cromberger firm likewise employed gothic type in its earliest imprints. The first book printed in Roman type in Mexico was Alonso de la Veracruz's Recognitio summularum (Juan Pablos, 1554).

Doctrina christiana, y catecismo para instruccion de los indios, y de la...

1584

-

p. 48

p. 48Disappearance of Gothic Type

The use of gothic type in Mexican imprints had almost entirely ceased by the time a printing press arrived in Lima, and none of the early Lima imprints used gothic type.

Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana

1571

-

p. 160

p. 160First Type Cutter and Founder in America

Antonio de Espinosa went to New Spain at the request of Juan Pablos in 1550, to work for him as type cutter and founder. In 1558, he managed to break Pablos' monopoly and establish his own press. His second edition of Molina's Vocabulario (1571) is a tour de force, and an illustration of his vast typographical resources. Most folio volumes printed in Mexico were usually gathered in single sheets, but the 1571 Vocabulario, on the other hand, is a folio "in eights," that is four nested sheets per gathering.

Muestra de los caractéres que tiene la imprenta que fué de don Manuel ...

1814

-

p. 5

p. 5Choices, choices

Printers produced type specimens--broadsides or pamphlets demonstrating the range of their typographical materials--from as early as the fifteenth century. This specimen from nineteenth-century Mexico is, apparently, unique. Only one surviving specimen from Latin America dates from an earlier year.

F. Ioannis Nauarro Gaditani, Ordinis Minorum Regularis obseruanti[a]e : ...

1604

-

p. 13

p. 13Printed Music

Printed music appeared as early as 1554, and continued to be printed, in Mexico at least, through the early seventeenth century. After that point, it was either imported, or produced in manuscript. It only reappeared in Mexico in the eighteenth century, with the Regla de N. S. P. S. Francisco (José Bernardo de Hogal, 1728).

Commentarii ac quaestiones in vniuersam Aristotelis ac subtilissimi doct...

1610

-

p. 3

p. 3Two-Color Printing

Printing in red and black, typically the title page only, but occasionally elsewhere, was common in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The red was achieved by adding vermillion to the varnish, rather than lamp black. The title page of Valera's Commentarii, here shown in facsimile, is the first such printing in South America.

Synodo diocesana

1764

-

p. 7

p. 7Beyond Two-Color Printing

On rare occasions, other inks or colorants might be used, such as blue or green, as in the Synodo diocesana...

Prima oratio habita in regio ac pontificio angelopolitano seminario Sanc...

1770

-

p. 1

p. 1Beyond Two-Color Printing

... or, gold leaf as in the Prima oratio.

Sermon del gran privado de Christo el evangelista San Juan en la titular fiesta

1689

-

p. 35

p. 35Traces of Production

Ink was applied using horsehair filled leather balls to achieve a smooth and precise thickness. Here is an interesting example of bad inking revealing the edge of the ink ball due to uneven application of ink.

Gazeta de literatura de Mexico

-

p. 1

p. 1Imports

This entry from the Gazeta de México of 8 September 1789 notes that on the 22nd of the pervious month the Frigate Nuestra Señora del Carmen arrived from Cádiz with 42 boxes of letters for the press, 167 balones of paper, and 9 boxes of books.

4. Journeymen, Apprentices, and General Conditions of the Trade

Exequias funerales, y pompa lugubre, que la illustre augusta, y muy leal...

1645

-

p. 3

p. 3A Documented Apprentice

Apprentices in the Latin American book trade are poorly documented. One that we know of was Manuel de los Olivos, an orphan from Jeréz de la Frontera, Spain. On 30 January 1642, Olivos entered into apprenticeship with Juan Blanco de Alcázar in Puebla de los Angeles. Three years later, two books appeared with his name in the imprint, perhaps signaling that he had moved from apprentice to journeyman. No other books with his imprint appear in the bibliographical record, until 1665, when he began printing in Lima.

Auto de la fe celebrado en Lima a 23. de enero de 1639. Al tribunal del ...

1639

-

p. 7

p. 7Pedro de Cabrera of Seville was formally apprenticed to Jerónimo de Contreras on 31 March 1622. The apprenticeship was to last for four years, with Contreras providing food, clothing, and housing, along with 100 pesos per year. The contract was severed on 13 February 1624, however, as Cabrera's uncle summoned him to Potosí. His first imprint, the Carta de Barcelona of 1625, thus becomes something of a puzzle. By 1638, however, he assumed administration of the press belonging to Jerónimo de Soto Alvarado, the position his former master had held.

Disputatio celebris, ac singularis, circa fidei professionem

1623

-

p. 1

p. 1Possible Apprentices?

The Olivos texts raise questions that can be brought to the bibliographical record. Martin Pastrana, of Mexico, may have been related to Francisco Gómez de Pastrana, printer in Lima, who was, in turn, related to Pedro and Bartolome Gómez de Pastrana, printers in Seville. Might Pastrana's sole text, shown here, also indicate advancement from apprentice to journeyman?

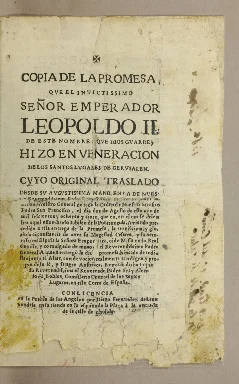

Copia de la promesa, que el invictissimo Señor Emperador Leopoldo II. [...

1685

-

p. 2

p. 2Working the Press

Once the compositor had set up the type, it would be moved to the press, inked, and a proof copy taken. Any errors would be corrected by unlocking the form in the press, extracting the errant sorts and replacing them with the correct ones as necessary. Proof copies are perhaps the most fugitive and ephemeral items from the hand press period. They would be pasted together and used to stiffen leather bindings, for example, or used to wrap bread, or otherwise destroyed. This unique proof sheet survived only because it was used as endpapers in another work. The crooked lines indicate that the form was not tightly locked into the press when taking the proof.

[Limosna, que en todos los reynos de las Indias, sus islas, y las Filipi...

1799

-

p. 1

p. 1Production Costs

An analysis of several hundred bills for printing jobs in New Spain reveals a remarkable stability in charges for composition and presswork: 7 pesos per sheet. The annotation on this file copy of a portion of a broadside notes the 14 pesos charged for setting and printing the two sheets.

Vocabulario dela lengua general de todo el Peru llamada lengua Qquichua,...

1608

-

p. 7

p. 7Assigning a Price

In Spain, for authors or printers granted exclusive privilege over one or another title, a reciprocal requirement was the tasa, or valuation. This was intended to ensure that exclusivity did not also engender exorbitant prices. Although the first tasas appeared in the fifteenth century, they became much more common in the 1530s and 1540s. The requirement was only abolished in 1762. Nevertheless, the tasa was almost non-existent in New Spain, and only somewhat more common in Peru. Holguín's Vocabulario was priced at one real per sheet, and the tasa notes the quarto volume required 90 sheets, resulting in a price of 11 pesos, 2 reales, equivalent to almost one month's pay for apprentice Pedro de Cabrera mentioned previously.

Cartilla mayor, en lengua castellana, latina, y mexicana

1693

-

p. 5

p. 5Monopolies

Cartillas were printed in the tens of thousands, but as reading primers, were usually read to death. They were sold for a fixed price of 1/2 real each. They were essential texts, and the monopoly privilege on their sale was quite profitable. It was granted to the cathedral of Valladolid, Spain, in the sixteenth century, and in New Spain, was granted to the Royal Hospital of the Indians. As neither operated their own press, the rights were assigned to local printers, who often competed fiercely for the monopoly. The license and privilege specifically note that infractions would be punished with a fine of 200 pesos and loss of "moldes," which is to say, the printing equipment.

Poeticarum institutionum liber, variis ethnicorum, christianorumque exem...

1605

-

p. 5

p. 5In a similar fashion, the Congregación de la Anunciata, a Jesuit religious brotherhood, held the monopoly on Latin textbooks used in the Jesuit colegios. Llanos' Poeticarvm institvtionvm liber shows their arms on the title page.

El peregrino septentrional Atlante: delineado en la exemplarissima vida ...

1737

-

p. 3

p. 3The Limits of Censorship

As two copies of the Peregrino septentrional Atlante make plain, the Inquisition's efforts at censorship were not always entirely successful. Inquisition censorship was not a simple binary of permitted and prohibited texts. Emendations of words or paragraphs were far more frequent. Occasionally, as here, such expurgations were simply pro forma, with no attempt made to fully obliterate the underlying text.

Replica apologetica, y satisfactoria al defensorio del M. R. P. Fr. Juan...

1773

-

p. 3

p. 3Banned Books

As the broadside above makes clear, some readers were given license to read prohibited texts. This text, in support of probabilism, was ordered prohibited in its entirety, as the notation on the endpaper indicates. It may have been a copy retained by the Holy Office itself.

5. Bookbinding

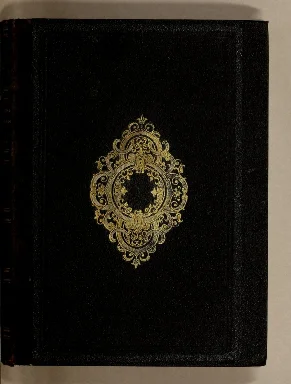

Paranympho celeste

1686

-

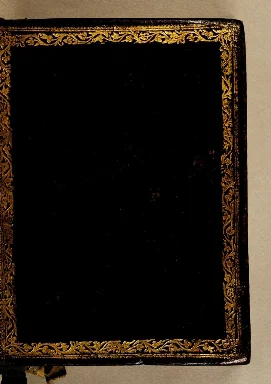

p. 1

p. 1Limp Vellum

Simply owing to its great availability and low cost, laced case limp parchment bindings made from sheepskins (usually referred to as vellum) were the most common throughout Latin America, and Spain as well.

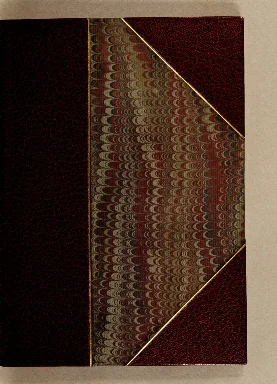

Teatro mexicano

1697-1698

-

p. 1

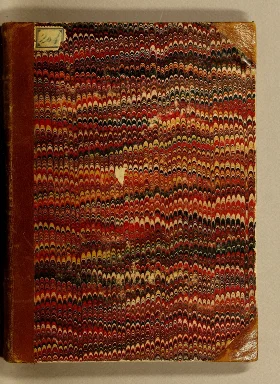

p. 1Spanish Pasteboard Binding

When books were bound in boards, the most frequent style is known as pasta española.

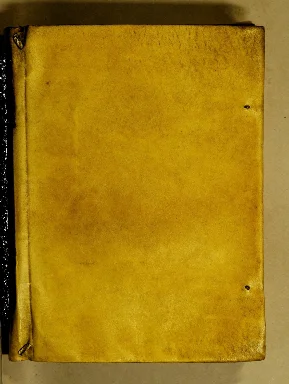

Aqui comiença vn vocabulario enla lengua castellana y mexicana

1555

-

p. 1

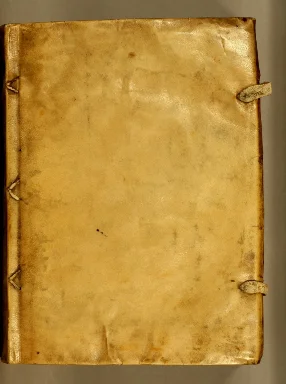

p. 1Sixteenth-century Boards

Sixteenth-century bindings on Latin American books are quite uncommon, for a variety of reasons. The majority of books produced in the period--dictionaries, grammars, collections of sermons, etc.--saw heavy use, often in the field, not in a library and thus suffered great wear. This copy of Molina's Vocabulario, however, conserves its original binding and is one of the few complete copies known.

En la gran ciudad de Mexico, de la Nueva Espana a ocho dias del mes de m...

1609

-

p. 1

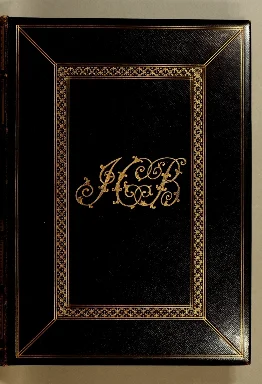

p. 1"Plateresque" Binding

The blind stamping and gold tooling of this binding is known as plateresque style. This early seventeenth-century plateresque binding, likely done in Mexico, is very uncommon. Despite its flaws, it nevertheless demonstrates a craftsmanship and attention to detail beyond the commonplace. This book also includes one of the earliest copper plate engravings done in Mexico.

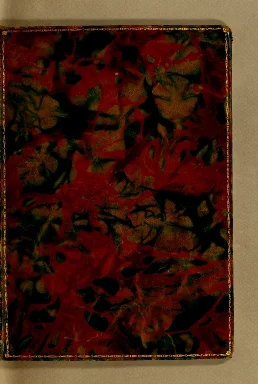

Luz de verdades catholicas y explicacion de la doctrina christiana

1691-1696

-

p. 1

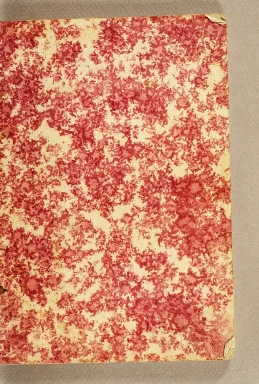

p. 1Fabric Bindings

Fabric bindings were often reserved for presentation copies, such as these bindings in silk and velvet. Even more rarely, some books were bound in silver. Two copies of José Gil Ramírez's Esfera Mexicana (Mexico: Viuda de Miguel de Ribera, 1714), which celebrated the birth of the third son of Philip V, were bound in silver for presentation to the king.

Arte de la lengua metropolitana del reyno Cakchiquel, o Guatemalico

1753

-

p. 1

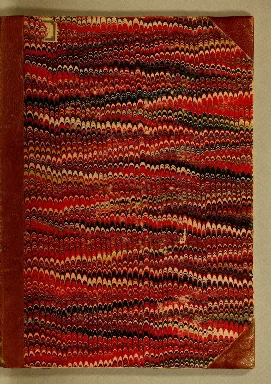

p. 1Edition Binding

These two copies of Flores' grammar of Kaqchikel are bound in an identical fashion, strongly suggesting they were "edition bound" at the time of their printing. Indeed, an analysis of hundreds of billing records from Mexico indicates that binding costs were routinely included with book orders.

5.1. A Single Hand at Work?

6. Content and Character of the Products of the Press

Arte de la lengua general del Reyno de Chile, con un dialogo chileno-his...

1765

-

p. 7

p. 7Indigenous Languages

The necessity of producing indigenous language texts drove the introduction of the printing press in both New Spain and Peru. While it was certainly possible to send manuscripts to Spain for printing, this would entail delay, and worse, a great potential for errors if the author were not there to correct the proofs. A large percentage of the early books produced in America were in native languages, and, after a dip in the seventeenth century, their printing became more frequent again in the eighteenth century. This text, in Mapuche, is one of nearly 8,000 books the JCB has contributed to the Internet Archive. Among these, it is the most popular, having been downloaded over 3,000 times.

Don Melchor de Nauarra y Rocafull, cauallero del Orden de Alcantara, duq...

1682

-

p. 3

p. 3Laws

While the press served the clerical establishment with texts to assist with the evangelization of the native population, the secular establishment had need for printed laws, bandos, reales cedulas, and the like.

Informe, que haze la Provincia de la Compañia de Jesus, de esta Nueba E...

-

p. 1

p. 1Legal Briefs

In The Colonial Printer, Lawrence Wroth wrote of British North America: "In examining the records of the colonial communities, one is appalled by the amount of legal and official business that was transacted in this new country, but whoever else may have been the sufferer by this frequent lawing, it is certain that it was not the printer." Much the same can be said of Spanish America and the vast number of legal briefs that were printed to accompany litigation.

Grandeza mexicana

1604

-

p. 230

p. 230Literature and Poetry

Relatively few works of a purely literary nature were printed in Spanish America. Given their great popularity and relatively low cost to print, it seems odd that no comedias were reprinted in the Americas. On the other hand, poetry flourished. Beyond texts such as the Grandeza Mexicana, a long poem on the riches and diversity of Mexico, a good number of texts in other genres were prefaced by laudatory odes. Here the text is opened to the verse on booksellers, engravers, and printers.

Villancicos, que se cantaron en los maytines de el glorioso principe de ...

1692

-

p. 1

p. 1Music

Similarly, while music had been printed in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, it was not until the later eighteenth century that it again appeared. Texts meant to be accompanied by music, such as Sor Juana's Villancicos, were very popular, however.

Practica de testamentos, en que se resuelven los casos mas frequentes, q...

1755

-

p. 1

p. 1Practical Guides

Pedro Murillo's Practica de testamentos was first published in Manila in 1745, and on multiple occasions thereafter, into the nineteenth century. It provides a clear and concise distillation of relevant laws related to the composition and content of last wills. While primarily intended for notaries, it also notes occasions and methods for writing testaments when notaries were not available. Interestingly, this 1755 edition, published by the heirs of María Candelária de Rivera, was funded by Antonio Adan, who did her testament the previous year.

Libro de plata reduzida que trata de leyes baias desde 20. marcos, hasta 120

1607

-

p. 24

p. 24Vade Mecum

Handbooks and aids to commerce were essential tools for merchants and miners. The earliest published in the Americas date to the sixteenth century. This guide to the value of silver of various degrees of purity saw heavy use in the field.

Vida de San Felipe de Jesus

1801

-

p. 1

p. 1Illustrations and Engravings

Even the earliest imprints in Spanish America included some type of illustrations, usually woodblocks. The first copperplate engravings to appear in print were in Mexico in 1609. While woodblocks could be printed along with the type, copperplates required a separate press. By the end of the seventeenth century, engravers had established their own shops, as did Montes de Oca, a prolific engraver who studied at the Academia de San Carlos. He eventually moved to Queretaro where he opened a school of art.

Gazeta de Mexico

1784-1809

-

p. 1

p. 1Periodicals

The precursors of the periodical press were the relaciones de sucessos, news-sheets that generally mentioned singular events. The first periodical in Spanish America was the Gazeta de México, which was issued during the first six months of 1722. While a second run followed some years later, it was not until the later eighteenth century that continuous publication was established.

Mercurio peruano de historia, literatura, y noticias públicas que da à...

1791-1795

-

p. 7

p. 7Scientific and Literary Press

Literary and scientific periodicals began to appear in the later eighteenth century. The Gazeta de literatura in Mexico, and the Mercurio Peruano in Lima introduced their readers to contemporary European developments in the sciences, often closely attuned to their local New World contexts.

Almanak y kalendario general diario de quartos de luna, segun el meridia...

1796

-

p. 5

p. 5Almanacs

Almanacs were published on an annual basis as early as the seventeenth century. Virtually all of these are known only from documentary evidence since so few survive. Even later almanacs are rather scarce, given their ephemeral nature.

El conocimiento de los tiempos, efemeride del año de 1790

1789

-

p. 3

p. 3Almanacs

Calendario manual y guia de forasteros en Mexico, para el año de 1796. Bisexto

1795

-

p. 1

p. 1City Guides

A similar genre, often issued together with an almanac was the guia de forasteros, or guide to the civil and ecclesiastical hierarchy. In Mexico, Zúñiga y Ontiveros obtained a monopoly on these profitable texts. The 12mo format, tall and narrow, clearly marks it as a book intended to be carried with its owner.

Cartilla mayor, en lengua castellana, latina, y mexicana

1691

-

p. 5

p. 5Reading Primers

Primers of reading and religious fundamentals, known as cartillas were published in the tens of thousands, however, extraordinarily few survive. They appeared in one, two, and occasionally three languages and were frequently read to death. Printers jealously guarded their monopoly privileges over these pamphlets. Despite a low fixed price of 1/2 real each, and an annual alms payment for the privilege, these were very lucrative titles.

B.L.M. su mayor servidor D. Joseph de Borda y Echeverria

-

p. 3

p. 3Ephemera

Ephemeral items like these invitations were a printer's bread and butter. Easily and quickly set up and printed, they ensured a steady cash flow between other larger jobs.

B.L.M. Al señor [...]

1792-1796

-

p. 3

p. 3Ephemera

Editorial Notes: Items Pending Integration

Credits

Project Creator(s)

- The John Carter Brown Library